Indo-grčko kraljevstvo

Indo-grčko kraljevstvo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 180 pne–10. godina | |||||||||

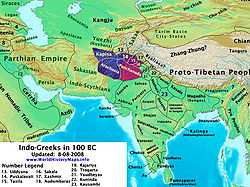

Teritorija Indo-grka oko 100 pne. | |||||||||

| Prestonica | Aleksandrija na Kavkazu (Kapisi/Bagram) Taksila (Sirkap) Činiotis (Činiot) Sagala (Sijalkot) Peukelaotis (Čarsada, Puškalavati) | ||||||||

| Zajednički jezici | Grčki (Grčki alfabet) Pali (Karošči pismo) Sanskrit Prakrit (Brahmi pismo) | ||||||||

| Religija | Grčki politeizam budizam hinduizam zoroastrianizam | ||||||||

| Vlada | Monarhija | ||||||||

| Kralj | |||||||||

• 180–160 pne | Apolodot I | ||||||||

• 25 pne – 10. | Strato II & Strato III | ||||||||

| Istorijska era | Antika | ||||||||

• Uspostavljen | 180 pne | ||||||||

• Ukinut | 10. godina | ||||||||

| Površina | |||||||||

| 150 pne[1] | 1.100.000 km2 (420.000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Danas deo | Avganistan Indija Pakistan Turkmenistan | ||||||||

Indo-grčko kraljevstvo ili Grčko-indijsko kraljevstvo[2] je bilo helenističko kraljevstvo koje se prostiralo od današnjeg Avganistana, u klasičnim ograničenjima Pundžaba Indijskog potkontinenta (severni Pakistan i severozapadna Indija),[3][4][5][6][7][8] tokom poslednja dva veka pre nove ere. Kraljevstvom je vladalo više od trideset kraljeva, često u međusobnom sukobu.

Kraljevstvo je osnovano kada je grčko-baktrijski kralj Demetrije napao potkontinent početkom drugog veka pre nove ere. Grci na Indijskom potkontinentu su na kraju odvojeni od Grko-baktrijaca koncentrisanih u Baktriji (sada granici između Avganistana i Uzbekistana), i Indo-grka u današnjem severozapadnom Indijskom potkontinentu. Najpoznatiji indo-grčki vladar bio je Menander (Milinda). On je imao prestonicu u Sakali u Pundžabu (današnjem Sialkotu).

Izraz „Indo-grčko kraljevstvo” labavo opisuje niz različitih dinastičkih politika, koje su tradicionalno povezane sa velikim brojem regionalnih prestonica, kao što je Taksila[9] (moderni Pandžab (Pakistan)), Puškalavati i Sagala.[10] Drugi potencijalni centri su samo nagovešteni; na primer, Ptolomejeva Geografija i nomenklatura kasnijih kraljeva sugerišu da je izvesni Teofil na jugu indo-grčke sfere uticaja takođe mogao biti satrapno ili kraljevsko sedište u jednom trenutku.

Tokom dva veka njihove vladavine, indo-grčki kraljevi su kombinovali grčke i indijske jezike i simbole, kao što se vidi na njihovim kovanicama, i mešali grčke i indijske ideje, kao što se vidi u arheološkim ostacima.[11] Rasprostranjenost indo-grčke kulture imala je posledice koje se i danas osećaju, naročito kroz uticaj grčko-budističke umetnosti.[12] Etnička pripadnost Indo-grka je možda u određenoj meri hibridna. Eutidem I bio je, prema Polibiju,[13] Magnezijski Grk. Njegov sin, Demetrijus I, osnivač Indo-grčkog kraljevstva, bio je stoga grčkog etničkog porekla barem po ocu. Dogovor o braku je sklopljen za Demetrija sa kćerkom seleukidskog vladara Antioha III (koji je delom imao persijsko poreklo).[14] Etnička pripadnost kasnijih indo-grčkih vladara je ponekad manje jasna.[15] Na primer, pretpostavlja se da je Artemidoros (80. pne) bio indo-skitskog porekla, iako je to sada sporno.[16]

Nakon smrti Menandera, veći deo njegovog carstva je razbijen i indo-grčki uticaj je znatno smanjen. Mnoga nova kraljevstva i republike istočno od reke Ravi počele su da prave nove kovanice koje prikazuju vojne pobede.[17] Najistaknutiji entiteti koji su se formirali bile su republika Jaudeja, Arjunajanas i Audumbaras. Jaudeja i Arjunajanas su obe tvrdile da su osvojile „pobedu mačem”.[18] U Maturi su ubrzo sledile dinastija Data i dinastija Mitra. Indo-grci su na kraju nestali kao politički entitet oko 10. godine nakon invazije Indo-skita, iako su se enklave grčkih populacija verovatno zadržale tokom nekoliko vekova pod kasnijom vladavinom Indo-partijanaca i Kušana.[19]

Reference[уреди | уреди извор]

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (1979). „Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.”. Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 132. JSTOR 1170959. doi:10.2307/1170959.

- ^ As in other compounds such as "African-American", "Asian-American", "French-Canadian" and so on, the nationality or race of the newcomers usually comes first, and the area of arrival comes second, so that "Greco-Indian" is normally a more accurate nomenclature than "Indo-Greek". The latter however has become the general usage, especially since the publication of Narain's book The Indo-Greeks. In Thomas McEvilley 2002 "The Shape of Ancient Greek Thought" p. 395 Note 52

- ^ Jackson J. Spielvogel (14. 9. 2016). Western Civilization: Volume A: To 1500. Cengage Learning. стр. 96. ISBN 978-1-305-95281-2. „The invasion of India by a Greco-Bactrian army in ... led to the creation of an Indo-Greek kingdom in northwestern India (present-day India and Pakistan).”

- ^ Zürcher, Erik (1962). Buddhism: its origin and spread in words, maps, and pictures. St Martin's Press. стр. 45. „Three phases must be distinguished, (a) The Greek rulers of Bactria (the Oxus region) expand their power to the south, conquer Afghanistan and considerable parts of north-western India, and establish an Indo-Greek kingdom in the Panjab where they rule as 'kings of India'; i”

- ^ Roupp, Heidi (4. 3. 2015). Teaching World History: A Resource Book. Routledge. стр. 171. ISBN 978-1-317-45893-7. „There were later Indo-Greek kingdoms in northwest India. ...”

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. стр. 74. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4. „They are referred to as 'Indo-Greeks' and there were about forty such kings and rulers who controlled large areas of northwestern India and Afghanistan. Their history ...”

- ^ Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Pal, Pratapaditya (1986). Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700. University of California Press. стр. 15. ISBN 978-0-520-05991-7. „Since parts of their territories comprised northwestern India, these later rulers of Greek origin are generally referred to as Indo-Greeks.”

- ^ Aruz, Joan; Elisabetta Valtz Fino (2012). Afghanistan: Forging Civilizations Along the Silk Road. Metropolitan Museum of Art. стр. 42. ISBN 978-1-58839-452-1. „The existence of Greek kingdoms in Central Asia and northwestern India after Alexander's conquests had been known for a long time from a few fragmentary texts from Greek and Latin classical sources and from allusions in contemporary Chinese chronicles and later Indian texts.”

- ^ Mortimer Wheeler Flames over Persepolis (London, 1968). Pp. 112 ff. It is unclear whether the Hellenistic street plan found by Sir John Marshall's excavations dates from the Indo-Greeks or from the Kushans, who would have encountered it in Bactria; Tarn (1951, pp. 137, 179) ascribes the initial move of Taxila to the hill of Sirkap to Demetrius I, but sees this as "not a Greek city but an Indian one"; not a polis or with a Hippodamian plan.

- ^ "Menander had his capital in Sagala" Bopearachchi, "Monnaies", p. 83. McEvilley supports Tarn on both points, citing Woodcock: "Menander was a Bactrian Greek king of the Euthydemid dynasty. His capital (was) at Sagala (Sialkot) in the Punjab, "in the country of the Yonakas (Greeks)"." McEvilley, p. 377. However, "Even if Sagala proves to be Sialkot, it does not seem to be Menander's capital for the Milindapanha states that Menander came down to Sagala to meet Nagasena, just as the Ganges flows to the sea."

- ^ "A vast hoard of coins, with a mixture of Greek profiles and Indian symbols, along with interesting sculptures and some monumental remains from Taxila, Sirkap and Sirsukh, point to a rich fusion of Indian and Hellenistic influences", India, the Ancient Past, Burjor Avari, p. 130

- ^ Ghose, Sanujit (2011). "Cultural links between India and the Greco-Roman world". Ancient History Encyclopedia

- ^ 11.34

- ^ Polybius 11.34

- ^ ("Notes on Hellenism in Bactria and India". W. W. Tarn. Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 22 (1902), pp. 268–293).

- ^ Osmund Bopearachchi Was Indo-Greek Artemidoros the son of Indo-Sctythian Maues

- ^ "Most of the people east of the Ravi already noticed as within Menander's empire -Audumbaras, Trigartas, Kunindas, Yaudheyas, Arjunayanas- began to coins in the first century BC, which means that they had become independent kingdoms or republics.", Tarn, The Greeks in Bactria and India

- ^ Tarn, William Woodthorpe (24. 6. 2010). The Greeks in Bactria and India. ISBN 9781108009416.

- ^ "When the Greeks of Bactria and India lost their kingdom they were not all killed, nor did they return to Greece. They merged with the people of the area and worked for the new masters; contributing considerably to the culture and civilization in southern and central Asia." Narain, "The Indo-Greeks" 2003, p. 278

Literatura[уреди | уреди извор]

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The ancient past. A history of the Indian sub-continent from c. 7000 BC to AD 1200. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9.

- Banerjee, Gauranga Nath (1961). Hellenism in ancient India. Delhi: Munshi Ram Manohar Lal. ISBN 978-0-8364-2910-7. OCLC 1837954.

- Bernard, Paul. "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. 1994. ISBN 92-3-102846-4. стр. 99–129..

- Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03680-9.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1991). Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (на језику: French). Bibliothèque Nationale de France. ISBN 978-2-7177-1825-6.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1998). SNG 9. New York: American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0-89722-273-0.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (на језику: French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 978-2-9516679-2-1.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1993). Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 36240864.

- Bussagli, Mario; Tissot, Francine; Béatrice Arnal (1996). L'art du Gandhara (на језику: French). Paris: Librairie générale française. ISBN 978-2-253-13055-0.

- Cambon, Pierre (2007). Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés (на језику: French). Musée Guimet. ISBN 978-2-7118-5218-5.

- Errington, Elizabeth; Cribb, Joe; Claringbull, Maggie; Ancient India and Iran Trust; Fitzwilliam Museum (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Cambridge: Ancient India and Iran Trust. ISBN 978-0-9518399-1-1.

- Faccenna, Domenico (1980). Butkara I (Swāt, Pakistan) 1956–1962, Volume III 1. Rome: IsMEO (Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente).

- Foltz, Richard (2010). Religions of the Silk Road: premodern patterns of globalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1.

- Keown, Damien (2003). A Dictionary of Buddhism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860560-7.

- Lowenstein, Tom (2002). The vision of the Buddha: Buddhism, the path to spiritual enlightenment. London: Duncan Baird. ISBN 978-1-903296-91-2.

- Marshall, Sir John Hubert (2000). The Buddhist art of Gandhara: the story of the early school, its birth, growth, and decline. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 978-81-215-0967-1.

- Marshall, John (1956). Taxila. An illustrated account of archaeological excavations carried out at Taxila (3 volumes). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts. ISBN 978-1-58115-203-6.

- Mitchiner, John E.; Garga (1986). The Yuga Purana: critically edited, with an English translation and a detailed introduction. Calcutta, India: Asiatic Society. ISBN 978-81-7236-124-2. OCLC 15211914.

- Narain, A.K. (1957). The Indo-Greeks. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- reprinted by Oxford, 1962, 1967, 1980; reissued (2003), "revised and supplemented", by B. R. Publishing Corporation, New Delhi.

- Narain, A.K. (1976). The coin types of the Indo-Greeks kings. Chicago, USA: Ares Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89005-109-2.

- Puri, Baij Nath (2000). Buddhism in Central Asia. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5.

- Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-81-215-0579-6.

- Salomon, Richard. „The "Avaca" Inscription and the Origin of the Vikrama Era”. 102.

- Seldeslachts, E. (2003). The end of the road for the Indo-Greeks?. (Also available online): Iranica Antica, Vol XXXIX, 2004.

- Senior, R. C. (2006). Indo-Scythian coins and history. Volume IV. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9709268-6-9.

- Tarn, W. W. (1938). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press.

- Second edition, with addenda and corrigenda, (1951). Reissued, with updating preface by Frank Lee Holt (1985), Ares Press, Chicago ISBN 978-0-89005-524-3.

- Afghanistan, ancien carrefour entre l'est et l'ouest (на језику: French и енглески). Belgium: Brepols. 2005. ISBN 978-2-503-51681-3.

- 東京国立博物館 (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan); 兵庫県立美術館 (Hyogo Kenritsu Bijutsukan) (2003). Alexander the Great: East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan. Tokyo: 東京国立博物館 (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan). OCLC 53886263.

- Vassiliades, Demetrios (2000). The Greeks in India – A Survey in Philosophical Understanding. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Limited. ISBN 978-81-215-0921-3.

- Vassiliades, Demetrios (2016). Greeks and Buddhism: An Intercultural Encounter. Athens: Indo-Hellenic Society for Culture and Development. ISBN 978-618-82624-0-9.

Spoljašnje veze[уреди | уреди извор]

- Indo-Greek history and coins

- Ancient coinage of the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms

- Text of Prof. Nicholas Sims-Williams (University of London) mentioning the arrival of the Kushans and the replacement of Greek Language.

- Wargame reconstitution of Indo-Greek armies

- Files dealing with Indo-Greeks & a genealogy of the Bactrian kings

- The impact of Greco-Indian Culture on Western Civilisation

- Some new hypotheses on the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms by Antoine Simonin

- Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek Kingdoms in Ancient Texts