Лобања — разлика између измена

оба облика су правилна, видети Речник српскога језика |

. |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{short description|Коштана структура која формира главу код кичмењака}}{{рут}} |

|||

{{Infobox anatomy |

|||

| Name = Лобања |

|||

| System = [[Скелетни систем]] |

|||

| image = VolRenderShearWarp.gif |

|||

| Caption = [[Volume rendering]] of a [[mouse]] skull |

|||

| Image2 = |

|||

| Caption2 = |

|||

| IsPartOf = |

|||

| Components = |

|||

| Artery = |

|||

| Vein = |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Датотека:Catskull.jpg|мини|десно|250п|[[Кости главе]] мачке — лобања и вилице]] |

[[Датотека:Catskull.jpg|мини|десно|250п|[[Кости главе]] мачке — лобања и вилице]] |

||

[[Датотека:Reconstrução facial - crânio - Cáceres-MT.stl|мини|Лобања ''Homo sapiensa'' — 3D]] |

[[Датотека:Reconstrução facial - crânio - Cáceres-MT.stl|мини|250п|Лобања ''Homo sapiensa'' — 3D]] |

||

'''Лобања''' или '''лубања''' ({{јез-лат|cranium}}) или '''лобањска/кранијална чаура''' обухвата све оне кости које чине компактни коштани овој у коме је смештен [[мозак]].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Надежда А. Јеличић |title=Анатомија човека – глава и врат |publisher=Савремена администрација |location=Београд |year=2000 |isbn=978-86-387-0604-4|pages=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Нева Л. Лотрић |title=Дескриптивна и топографска анатомија човека |publisher=[[Научна књига]] |location=Београд, Загреб |year=1987}}</ref> |

'''Лобања''' или '''лубања''' ({{јез-лат|cranium}}) или '''лобањска/кранијална чаура''' обухвата све оне кости које чине компактни коштани овој у коме је смештен [[мозак]].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Надежда А. Јеличић |title=Анатомија човека – глава и врат |publisher=Савремена администрација |location=Београд |year=2000 |isbn=978-86-387-0604-4|pages=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Нева Л. Лотрић |title=Дескриптивна и топографска анатомија човека |publisher=[[Научна књига]] |location=Београд, Загреб |year=1987}}</ref> It supports the structures of the face and provides a protective [[Cranial cavity|cavity]] for the brain.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/skull|title=skull|website=[[Merriam-Webster Dictionary]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150217083723/http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/skull|archive-date=17 February 2015|url-status=live|df=dmy-all}}</ref> The skull is composed of two parts: the '''cranium''' and the [[mandible]]<ref>{{Cite book|author =Tim D. White, Michael T. Black, Pieter Arend Folkens|title=Human Osteology (3rd ed.)|publisher=Academic Press |

||

|date=2011-01-21|page =51|isbn =9780080920856|url =https://books.google.com/books?id=oCSG2mYlD90C&dq=Human+Osteology+Tim+D.+White+PAGE+51&pg=PP1}}</ref>. In [[human]]s, these two parts are the [[neurocranium]] and the viscerocranium ([[facial skeleton]]) that includes the mandible as its largest bone. The skull forms the anterior-most portion of the [[skeleton]] and is a product of [[cephalisation]]—housing the brain, and several [[sensory system|sensory]] structures such as the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/science/cephalization|title=Cephalization: Biology|website=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160502000749/http://www.britannica.com/science/cephalization|archive-date=2 May 2016|url-status=live|access-date=23 April 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In humans these sensory structures are part of the facial skeleton. |

|||

Functions of the skull include protection of the brain, fixing the distance between the eyes to allow [[stereoscopic vision]], and fixing the position of the ears to enable [[sound localisation]] of the direction and distance of sounds. In some animals, such as horned [[ungulate]]s (mammals with hooves), the skull also has a defensive function by providing the mount (on the [[frontal bone]]) for the [[horn (anatomy)|horns]]. |

|||

The English word ''skull'' is probably derived from [[List of English words of Old Norse origin|Old Norse]] {{Lang|non|skulle}},<ref>{{Cite web|title=Definition of skull {{!}} Dictionary.com|url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/skull|access-date=2021-09-06|website=www.dictionary.com|language=en}}</ref> while the [[Latin]] word {{Lang|la|cranium}} comes from the [[Greek and Latin roots in English|Greek root]] {{Lang|grc|κρανίον}} ({{Lang|grc-latn|kranion}}). |

|||

The skull is made up of a number of fused [[flat bone]]s, and contains many [[foramina]], [[fossa (anatomy)|fossae]], [[process (anatomy)|processes]], and several cavities or [[sinus (anatomy)|sinuses]]. In [[zoology]] there are openings in the skull called [[fenestra]]e. |

|||

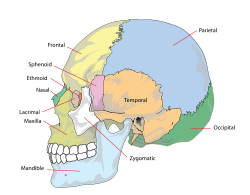

Коштани део [[глава|главе]] код већине [[кичмењаци|кичмењака]] изграђен је из лобање и костију [[вилица]]. Кичмењаци који имају компактну лобању називају се -{[[Craniata]]}-.<ref name="Gray's Anatomy40th">{{Gray's Anatomy40th}}</ref> Кости лобање чине: чеона кост, темена кост, клинаста кост, слепоочна кост, потиљачна кост и ситаста кост. |

Коштани део [[глава|главе]] код већине [[кичмењаци|кичмењака]] изграђен је из лобање и костију [[вилица]]. Кичмењаци који имају компактну лобању називају се -{[[Craniata]]}-.<ref name="Gray's Anatomy40th">{{Gray's Anatomy40th}}</ref> Кости лобање чине: чеона кост, темена кост, клинаста кост, слепоочна кост, потиљачна кост и ситаста кост. |

||

== Структура == |

|||

=== Humans{{anchor|Structure_of_human_skull}} === |

|||

{{about||details and the constituent bones|Neurocranium|and|Facial skeleton}} |

|||

[[File:Lateral head skull.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Skull in situ]] |

|||

[[File:621 Anatomy of a Flat Bone.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Anatomy of a flat bone - the periosteum of the neurocranium is known as the [[periosteum|pericranium]]]] |

|||

[[File:Sobo 1909 38.png|thumb|right|250px|Human skull from the front]] |

|||

[[File:Human skull side simplified (bones).svg|thumb|right|250px|Side bones of skull]] |

|||

The '''human skull''' is the bone structure that forms the [[human head|head]] in the [[human skeleton]]. It supports the structures of the [[human face|face]] and forms a cavity for the [[Human brain|brain]]. Like the skulls of other vertebrates, it protects the brain from injury.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NiTLf7g1n04C|title=Anatomy Coloring Workbook|last=Alcamo|first=I. Edward|date=2003|publisher=The Princeton Review|isbn=9780375763427|pages=22–25|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The skull consists of three parts, of different [[embryology|embryological]] origin—the [[neurocranium]], the '''sutures,''' and the [[facial skeleton]] (also called the ''membraneous viscerocranium''). The neurocranium (or ''braincase'') forms the protective [[cranial cavity]] that surrounds and houses the brain and [[brainstem]].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M8WgDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA2|title=Comprehensive and Clinical Anatomy of the Middle Ear|last1=Mansour|first1=Salah|last2=Magnan|first2=Jacques|last3=Ahmad|first3=Hassan Haidar|last4=Nicolas|first4=Karen|last5=Louryan|first5=Stéphane|date=2019|publisher=Springer|isbn=9783030153632|pages=2|language=en}}</ref> The upper areas of the [[neurocranium|cranial bones]] form the [[calvaria (skull)|calvaria]] (skullcap). The membranous viscerocranium includes the [[mandible]]. |

|||

The sutures are fairly rigid joints between bones of the neurocranium. |

|||

The facial skeleton is formed by the bones supporting the face. |

|||

== Клинички знача == |

|||

[[Craniosynostosis]] is a condition in which one or more of the fibrous [[Suture (joint)|sutures]] in an infant skull prematurely fuses,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thefetus.net/page.php?id=340|title=Cloverleaf skull or kleeblattschadel|last1=Silva|first1=Sandra|last2=Jeanty|first2=Philippe|date=1999-06-07|work=TheFetus.net|publisher=MacroMedia|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080213205927/http://www.thefetus.net/page.php?id=340|archive-date=13 February 2008|url-status=dead|access-date=2007-02-03|df=dmy-all}}</ref> and changes the growth pattern of the skull.<ref name="Brief Review">{{cite journal|last1=Slater|first1=Bethany J.|last2=Lenton|first2=Kelly A.|last3=Kwan|first3=Matthew D.|last4=Gupta|first4=Deepak M.|last5=Wan|first5=Derrick C.|last6=Longaker|first6=Michael T.|date=April 2008|title=Cranial Sutures: A Brief Review|journal=[[Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery]]|volume=121|issue=4|pages=170e–8e|doi=10.1097/01.prs.0000304441.99483.97|pmid=18349596|s2cid=34344899}}</ref> Because the skull cannot expand perpendicular to the fused suture, it grows more in the parallel direction.<ref name="Brief Review" /> Sometimes the resulting growth pattern provides the necessary space for the growing brain, but results in an abnormal head shape and abnormal facial features.<ref name="Brief Review" /> In cases in which the compensation does not effectively provide enough space for the growing brain, craniosynostosis results in increased [[intracranial pressure]] leading possibly to visual impairment, sleeping impairment, eating difficulties, or an impairment of mental development.<ref name="Intracranial pressure">{{cite journal|last1=Gault|first1=David T.|last2=Renier|first2=Dominique|last3=Marchac|first3=Daniel|last4=Jones|first4=Barry M.|date=September 1992|title=Intracranial Pressure and Intracranial Volume in Children with Craniosynostosis|journal=[[Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery]]|volume=90|issue=3|pages=377–81|doi=10.1097/00006534-199209000-00003|pmid=1513883}}</ref> |

|||

A [[copper beaten skull]] is a phenomenon wherein intense [[intracranial pressure]] disfigures the internal surface of the skull.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://radiopaedia.org/articles/copper-beaten-skull|title=Copper beaten skull|last=Gaillard|first=Frank|website=[[Radiopaedia]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180425234432/https://radiopaedia.org/articles/copper-beaten-skull|archive-date=25 April 2018|url-status=live|access-date=25 April 2018|df=dmy-all}}</ref> The name comes from the fact that the inner skull has the appearance of having been beaten with a [[ball-peen hammer]], such as is often used by [[coppersmith]]s. The condition is most common in children. |

|||

=== Повреде и третман === |

|||

Injuries to the brain can be life-threatening. Normally the skull protects the brain from damage through its hard unyieldingness; the skull is one of the least deformable structures found in nature with it needing the force of about 1 ton to reduce the diameter of the skull by 1 cm.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Holbourn|first=A. H. S.|date=9 October 1943|title=Mechanics of Head Injuries|journal=[[The Lancet]]|volume=242|issue=6267|pages=438–41|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(00)87453-X}}</ref> In some cases, however, of [[head injury]], there can be raised [[intracranial pressure]] through mechanisms such as a [[subdural haematoma]]. In these cases the raised intracranial pressure can cause herniation of the brain out of the [[foramen magnum]] ("coning") because there is no space for the brain to expand; this can result in significant [[brain damage]] or death unless an urgent operation is performed to relieve the pressure. This is why patients with [[concussion]] must be watched extremely carefully. |

|||

Dating back to [[Neolithic]] times, a skull operation called [[trepanning]] was sometimes performed. This involved drilling a ''burr'' hole in the cranium. Examination of skulls from this period reveals that the patients sometimes survived for many years afterward. It seems likely that trepanning was also performed purely for ritualistic or religious reasons. Nowadays this procedure is still used but is normally called a [[craniectomy]]. |

|||

In March 2013, for the first time in the U.S., researchers replaced a large percentage of a patient's skull with a precision, [[3D printing|3D-printed]] [[polymer]] [[Implant (medicine)|implant]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.medicaldaily.com/3d-printed-polymer-skull-implant-used-first-time-us-244583|title=3D-Printed Polymer Skull Implant Used For First Time in US|date=7 March 2013|website=Medical Daily|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130928042619/http://www.medicaldaily.com/3d-printed-polymer-skull-implant-used-first-time-us-244583|archive-date=28 September 2013|url-status=live|access-date=24 September 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> About 9 months later, the first complete cranium replacement with a 3D-printed plastic insert was performed on a Dutch woman. She had been suffering from [[hyperostosis]], which increased the thickness of her skull and compressed her brain.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dutchnews.nl/news/2014/03/dutch_hospital_gives_patient_n/|title=Dutch hospital gives patient new plastic skull, made by 3D printer|date=26 March 2014|website=DutchNews.nl|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140328121216/http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2014/03/dutch_hospital_gives_patient_n.php|archive-date=28 March 2014|url-status=live|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

A study conducted in 2018 by the researchers of [[Harvard Medical School]] in Boston, funded by [[National Institutes of Health|National Institutes of Health (NIH)]] suggested that instead of travelling via [[blood]], there are "tiny channels" in the skull through which the [[White blood cell|immune cells]] combined with the [[bone marrow]] reach the areas of [[inflammation]] after an injury to the brain tissues.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/322901.php|title=Newly discovered skull channels play role in immunity|last=Cohut|first=Maria|date=29 August 2018|work=[[Medical News Today]]|access-date=30 August 2018}}</ref> |

|||

===Transgender procedures=== |

|||

Surgical alteration of [[sexual dimorphism|sexually dimorphic]] skull features may be carried out as a part of [[facial feminization surgery]], a set of reconstructive surgical procedures that can alter male facial features to bring them closer in shape and size to typical female facial features.<ref name="SpiegelQoL">{{cite journal|last1=Ainsworth|first1=Tiffiny A.|last2=Spiegel|first2=Jeffrey H.|year=2010|title=Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery|journal=[[Quality of Life Research]]|volume=19|issue=7|pages=1019–24|doi=10.1007/s11136-010-9668-7|pmid=20461468|s2cid=601504}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Shams|first1=Mohammad Ghasem|last2=Motamedi|first2=Mohammad Hosein Kalantar|date=9 January 2009|title=Case report: Feminizing the male face|journal=ePlasty|volume=9|pages=e2|pmc=2627308|pmid=19198644}}</ref> These procedures can be an important part of the treatment of [[transgender]] people for [[gender dysphoria]].<ref name="wpathMedNed">World Professional Association for Transgender Health. [http://www.wpath.org/documents/Med%20Nec%20on%202008%20Letterhead.pdf WPATH Clarification on Medical Necessity of Treatment, Sex Reassignment, and Insurance Coverage in the U.S.A.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110930040306/http://www.wpath.org/documents/Med%20Nec%20on%202008%20Letterhead.pdf |date=30 September 2011 }} (2008).</ref><ref name="wpath2011">World Professional Association for Transgender Health. ''[http://www.wpath.org/documents/Standards%20of%20Care%20V7%20-%202011%20WPATH.pdf Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Version 7.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120303035205/http://www.wpath.org/documents/Standards%20of%20Care%20V7%20-%202011%20WPATH.pdf |date=3 March 2012 }}'' pg. 58 (2011).</ref> |

|||

== Види још == |

== Види још == |

||

| Ред 13: | Ред 68: | ||

== Литература == |

== Литература == |

||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|ref=harv|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Надежда А. Јеличић |title=Анатомија човека – глава и врат |publisher=Савремена администрација |location=Београд |year=2000 |isbn=978-86-387-0604-4|pages=}} |

* {{Cite book|ref=harv|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Надежда А. Јеличић |title=Анатомија човека – глава и врат |publisher=Савремена администрација |location=Београд |year=2000 |isbn=978-86-387-0604-4|pages=}} |

||

* {{Cite book|ref=harv|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Нева Л. Лотрић |title=Дескриптивна и топографска анатомија човека |publisher=[[Научна књига]] |location=Београд, Загреб |year=1987}} |

* {{Cite book|ref=harv|last=Јовановић,|first=Славољуб В. Нева Л. Лотрић |title=Дескриптивна и топографска анатомија човека |publisher=[[Научна књига]] |location=Београд, Загреб |year=1987}} |

||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

| Ред 21: | Ред 78: | ||

* [http://www.welovelmc.com/books/anatomy/cranialcavity.htm Анатомија кранијалне шупљине] |

* [http://www.welovelmc.com/books/anatomy/cranialcavity.htm Анатомија кранијалне шупљине] |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20071203234330/http://www.gwc.maricopa.edu/class/bio201/skull/skulltt.htm Приручник о анатомији главе] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20071203234330/http://www.gwc.maricopa.edu/class/bio201/skull/skulltt.htm Приручник о анатомији главе] |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20180430094506/http://www.csuchico.edu/anth/Module/skull.html Skull Module] ([[California State University]] Department of Anthology) |

|||

* [https://www.skullsite.com Bird Skull Collection] Bird skull database with very large collection of skulls (Agricultural University of Wageningen) |

|||

{{клица-животиње}} |

|||

* [http://www.uni-mainz.de/FB/Medizin/Anatomie/workshop/bones/skullbase.html Human skull base] (in German) |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20111119200906/http://www.somso.de/img/schaedel_en.pdf Human Skulls / Anthropological Skulls / Comparison of Skulls of Vertebrates ] (PDF; 502 kB) |

|||

{{нормативна контрола}} |

{{нормативна контрола}} |

||

{{Portal bar|Анатомија}}} |

|||

[[Категорија:Кости главе]] |

[[Категорија:Кости главе]] |

||

Верзија на датум 25. децембар 2021. у 23:10

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

| Лобања | |

|---|---|

Volume rendering of a mouse skull | |

| Детаљи | |

| Систем | Скелетни систем |

| Идентификатори | |

| MeSH | D012886 |

| FMA | 54964 |

| Анатомска терминологија | |

Лобања или лубања (лат. cranium) или лобањска/кранијална чаура обухвата све оне кости које чине компактни коштани овој у коме је смештен мозак.[1][2] It supports the structures of the face and provides a protective cavity for the brain.[3] The skull is composed of two parts: the cranium and the mandible[4]. In humans, these two parts are the neurocranium and the viscerocranium (facial skeleton) that includes the mandible as its largest bone. The skull forms the anterior-most portion of the skeleton and is a product of cephalisation—housing the brain, and several sensory structures such as the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth.[5] In humans these sensory structures are part of the facial skeleton.

Functions of the skull include protection of the brain, fixing the distance between the eyes to allow stereoscopic vision, and fixing the position of the ears to enable sound localisation of the direction and distance of sounds. In some animals, such as horned ungulates (mammals with hooves), the skull also has a defensive function by providing the mount (on the frontal bone) for the horns.

The English word skull is probably derived from Old Norse skulle,[6] while the Latin word cranium comes from the Greek root κρανίον (kranion).

The skull is made up of a number of fused flat bones, and contains many foramina, fossae, processes, and several cavities or sinuses. In zoology there are openings in the skull called fenestrae.

Коштани део главе код већине кичмењака изграђен је из лобање и костију вилица. Кичмењаци који имају компактну лобању називају се Craniata.[7] Кости лобање чине: чеона кост, темена кост, клинаста кост, слепоочна кост, потиљачна кост и ситаста кост.

Структура

Humans

The human skull is the bone structure that forms the head in the human skeleton. It supports the structures of the face and forms a cavity for the brain. Like the skulls of other vertebrates, it protects the brain from injury.[8]

The skull consists of three parts, of different embryological origin—the neurocranium, the sutures, and the facial skeleton (also called the membraneous viscerocranium). The neurocranium (or braincase) forms the protective cranial cavity that surrounds and houses the brain and brainstem.[9] The upper areas of the cranial bones form the calvaria (skullcap). The membranous viscerocranium includes the mandible.

The sutures are fairly rigid joints between bones of the neurocranium.

The facial skeleton is formed by the bones supporting the face.

Клинички знача

Craniosynostosis is a condition in which one or more of the fibrous sutures in an infant skull prematurely fuses,[10] and changes the growth pattern of the skull.[11] Because the skull cannot expand perpendicular to the fused suture, it grows more in the parallel direction.[11] Sometimes the resulting growth pattern provides the necessary space for the growing brain, but results in an abnormal head shape and abnormal facial features.[11] In cases in which the compensation does not effectively provide enough space for the growing brain, craniosynostosis results in increased intracranial pressure leading possibly to visual impairment, sleeping impairment, eating difficulties, or an impairment of mental development.[12]

A copper beaten skull is a phenomenon wherein intense intracranial pressure disfigures the internal surface of the skull.[13] The name comes from the fact that the inner skull has the appearance of having been beaten with a ball-peen hammer, such as is often used by coppersmiths. The condition is most common in children.

Повреде и третман

Injuries to the brain can be life-threatening. Normally the skull protects the brain from damage through its hard unyieldingness; the skull is one of the least deformable structures found in nature with it needing the force of about 1 ton to reduce the diameter of the skull by 1 cm.[14] In some cases, however, of head injury, there can be raised intracranial pressure through mechanisms such as a subdural haematoma. In these cases the raised intracranial pressure can cause herniation of the brain out of the foramen magnum ("coning") because there is no space for the brain to expand; this can result in significant brain damage or death unless an urgent operation is performed to relieve the pressure. This is why patients with concussion must be watched extremely carefully.

Dating back to Neolithic times, a skull operation called trepanning was sometimes performed. This involved drilling a burr hole in the cranium. Examination of skulls from this period reveals that the patients sometimes survived for many years afterward. It seems likely that trepanning was also performed purely for ritualistic or religious reasons. Nowadays this procedure is still used but is normally called a craniectomy.

In March 2013, for the first time in the U.S., researchers replaced a large percentage of a patient's skull with a precision, 3D-printed polymer implant.[15] About 9 months later, the first complete cranium replacement with a 3D-printed plastic insert was performed on a Dutch woman. She had been suffering from hyperostosis, which increased the thickness of her skull and compressed her brain.[16]

A study conducted in 2018 by the researchers of Harvard Medical School in Boston, funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) suggested that instead of travelling via blood, there are "tiny channels" in the skull through which the immune cells combined with the bone marrow reach the areas of inflammation after an injury to the brain tissues.[17]

Transgender procedures

Surgical alteration of sexually dimorphic skull features may be carried out as a part of facial feminization surgery, a set of reconstructive surgical procedures that can alter male facial features to bring them closer in shape and size to typical female facial features.[18][19] These procedures can be an important part of the treatment of transgender people for gender dysphoria.[20][21]

Види још

Референце

- ^ Јовановић,, Славољуб В. Надежда А. Јеличић (2000). Анатомија човека – глава и врат. Београд: Савремена администрација. ISBN 978-86-387-0604-4.

- ^ Јовановић,, Славољуб В. Нева Л. Лотрић (1987). Дескриптивна и топографска анатомија човека. Београд, Загреб: Научна књига.

- ^ „skull”. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Архивирано из оригинала 17. 2. 2015. г.

- ^ Tim D. White, Michael T. Black, Pieter Arend Folkens (2011-01-21). Human Osteology (3rd ed.). Academic Press. стр. 51. ISBN 9780080920856.

- ^ „Cephalization: Biology”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Архивирано из оригинала 2. 5. 2016. г. Приступљено 23. 4. 2016.

- ^ „Definition of skull | Dictionary.com”. www.dictionary.com (на језику: енглески). Приступљено 2021-09-06.

- ^ Susan Standring, ур. (2009) [1858]. Gray's anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, Expert Consult. illustrated by Richard E. M. Moore (40 изд.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-06684-9.

- ^ Alcamo, I. Edward (2003). Anatomy Coloring Workbook (на језику: енглески). The Princeton Review. стр. 22—25. ISBN 9780375763427.

- ^ Mansour, Salah; Magnan, Jacques; Ahmad, Hassan Haidar; Nicolas, Karen; Louryan, Stéphane (2019). Comprehensive and Clinical Anatomy of the Middle Ear (на језику: енглески). Springer. стр. 2. ISBN 9783030153632.

- ^ Silva, Sandra; Jeanty, Philippe (1999-06-07). „Cloverleaf skull or kleeblattschadel”. TheFetus.net. MacroMedia. Архивирано из оригинала 13. 2. 2008. г. Приступљено 2007-02-03.

- ^ а б в Slater, Bethany J.; Lenton, Kelly A.; Kwan, Matthew D.; Gupta, Deepak M.; Wan, Derrick C.; Longaker, Michael T. (април 2008). „Cranial Sutures: A Brief Review”. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 121 (4): 170e—8e. PMID 18349596. S2CID 34344899. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000304441.99483.97.

- ^ Gault, David T.; Renier, Dominique; Marchac, Daniel; Jones, Barry M. (септембар 1992). „Intracranial Pressure and Intracranial Volume in Children with Craniosynostosis”. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 90 (3): 377—81. PMID 1513883. doi:10.1097/00006534-199209000-00003.

- ^ Gaillard, Frank. „Copper beaten skull”. Radiopaedia. Архивирано из оригинала 25. 4. 2018. г. Приступљено 25. 4. 2018.

- ^ Holbourn, A. H. S. (9. 10. 1943). „Mechanics of Head Injuries”. The Lancet. 242 (6267): 438—41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)87453-X.

- ^ „3D-Printed Polymer Skull Implant Used For First Time in US”. Medical Daily. 7. 3. 2013. Архивирано из оригинала 28. 9. 2013. г. Приступљено 24. 9. 2013.

- ^ „Dutch hospital gives patient new plastic skull, made by 3D printer”. DutchNews.nl. 26. 3. 2014. Архивирано из оригинала 28. 3. 2014. г.

- ^ Cohut, Maria (29. 8. 2018). „Newly discovered skull channels play role in immunity”. Medical News Today. Приступљено 30. 8. 2018.

- ^ Ainsworth, Tiffiny A.; Spiegel, Jeffrey H. (2010). „Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery”. Quality of Life Research. 19 (7): 1019—24. PMID 20461468. S2CID 601504. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9668-7.

- ^ Shams, Mohammad Ghasem; Motamedi, Mohammad Hosein Kalantar (9. 1. 2009). „Case report: Feminizing the male face”. ePlasty. 9: e2. PMC 2627308

. PMID 19198644.

. PMID 19198644.

- ^ World Professional Association for Transgender Health. WPATH Clarification on Medical Necessity of Treatment, Sex Reassignment, and Insurance Coverage in the U.S.A. Архивирано 30 септембар 2011 на сајту Wayback Machine (2008).

- ^ World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Version 7. Архивирано 3 март 2012 на сајту Wayback Machine pg. 58 (2011).

Литература

- Јовановић,, Славољуб В. Надежда А. Јеличић (2000). Анатомија човека – глава и врат. Београд: Савремена администрација. ISBN 978-86-387-0604-4.

- Јовановић,, Славољуб В. Нева Л. Лотрић (1987). Дескриптивна и топографска анатомија човека. Београд, Загреб: Научна књига.

Спољашње везе

- Колекција животињских лобања (преко 300 животињских лобања, које је сакупио амерички средњошколски професор)

- Анатомија кранијалне шупљине

- Приручник о анатомији главе

- Skull Module (California State University Department of Anthology)

- Bird Skull Collection Bird skull database with very large collection of skulls (Agricultural University of Wageningen)

- Human skull base (in German)

- Human Skulls / Anthropological Skulls / Comparison of Skulls of Vertebrates (PDF; 502 kB)

}