Паралелност (геометрија) — разлика између измена

Нема описа измене |

. |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{Short description|Релација која се користи у геометрији}}{{rut}} |

|||

'''Паралелност''' у [[геометрија|геометрији]] представља однос између два геометријска објекта. Примери дефинисања паралелности у еуклидској геометрији су: |

|||

[[File:Parallel (PSF).png|thumb|Линијско цртање паралелних линија и кривих.|alt==]] |

|||

'''Паралелност''' у [[геометрија|геометрији]] представља однос између два геометријска објекта. Примери дефинисања паралелности у еуклидској геометрији су: |

|||

* Две [[права (линија)|праве]] су паралелне уколико се налазе у једној [[раван|равни]] и не секу се. |

* Две [[права (линија)|праве]] су паралелне уколико се налазе у једној [[раван|равни]] и не секу се. |

||

* Права је паралелна са равни, уколико са њом нема пресечних тачака. (еуклидски простор) |

* Права је паралелна са равни, уколико са њом нема пресечних тачака. (еуклидски простор) |

||

* Две различите равни су паралелне уколико се не секу. (еуклидски простор) |

* Две различите равни су паралелне уколико се не секу. (еуклидски простор) |

||

У тродимензионом простору треба разликовати појам паралелности и мимоилажења. Уколико две праве не леже у истој равни и не секу се, онда су исте '''мимоилазне''' а не паралелне. По сличном концепту постоји и појам '''мимоилазних равни''' у еуклидским просторима већих димензија. |

У тродимензионом простору треба разликовати појам паралелности и мимоилажења. Уколико две праве не леже у истој равни и не секу се, онда су исте '''мимоилазне''' а не паралелне. По сличном концепту постоји и појам '''мимоилазних равни''' у еуклидским просторима већих димензија. У [[еуклидов простор|еуклидском простору]] -{'''R'''}-<sup>-{''n''}-</sup>, за два [[афини простор|афина потпростора]] -{''a''}-<sub>1</sub> + -{''V''}-<sub>1</sub> и -{''a''}-<sub>2</sub> + -{''V''}-<sub>2</sub> каже се да су паралелни ако је један од одговарајућих [[векторски простор|векторских потпростора]] -{''V''}-<sub>1</sub> и -{''V''}-<sub>2</sub> потпростор другог. У геометријском простору тачака у којем је уведен појам [[бесконачност|бесконачно]] далеких тачака, два геометријска објекта су паралелна уколико се секу у бесконачно далекој тачки. |

||

Parallel lines are the subject of [[Euclid]]'s [[parallel postulate]].<ref>Although this postulate only refers to when lines meet, it is needed to prove the uniqueness of parallel lines in the sense of [[Playfair's axiom]].</ref> Parallelism is primarily a property of [[affine geometry|affine geometries]] and [[Euclidean geometry]] is a special instance of this type of geometry. |

|||

In some other geometries, such as [[hyperbolic geometry]], lines can have analogous properties that are referred to as parallelism. |

|||

== Симбол == |

|||

The parallel symbol is <math>\parallel</math>.<ref name="Kersey_1673"/><ref name="Cajori_1928"/> For example, <math>AB \parallel CD</math> indicates that line ''AB'' is parallel to line ''CD''. |

|||

In the [[Unicode]] character set, the "parallel" and "not parallel" signs have codepoints U+2225 (∥) and U+2226 (∦), respectively. In addition, U+22D5 (⋕) represents the relation "equal and parallel to".<ref>{{cite web| title = Mathematical Operators – Unicode Consortium| url = https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2200.pdf| access-date = 2013-04-21}}</ref> |

|||

The same symbol is used for a binary function in electrical engineering (the [[parallel operator]]). It is distinct from the double-vertical-line brackets that indicate a [[Norm (mathematics)|norm]], as well as from the logical or operator (<code>||</code>) in several programming languages. |

|||

== Еуклидски паралелизам == |

|||

===Two lines in a plane=== |

|||

====Conditions for parallelism==== |

|||

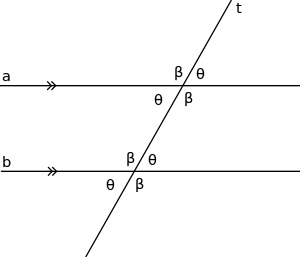

[[Image:Parallel transversal.svg|thumb|right|300px|As shown by the tick marks, lines ''a'' and ''b'' are parallel. This can be proved because the transversal ''t'' produces congruent corresponding angles <math>\theta</math>, shown here both to the right of the transversal, one above and adjacent to line ''a'' and the other above and adjacent to line ''b''.]] |

|||

Given parallel straight lines ''l'' and ''m'' in [[Euclidean space]], the following properties are equivalent: |

|||

#Every point on line ''m'' is located at exactly the same (minimum) distance from line ''l'' (''[[equidistant]] lines''). |

|||

#Line ''m'' is in the same plane as line ''l'' but does not intersect ''l'' (recall that lines extend to [[infinity]] in either direction). |

|||

#When lines ''m'' and ''l'' are both intersected by a third straight line (a [[Transversal (geometry)|transversal]]) in the same plane, the [[corresponding angles]] of intersection with the transversal are [[Congruence (geometry)|congruent]]. |

|||

Since these are equivalent properties, any one of them could be taken as the definition of parallel lines in Euclidean space, but the first and third properties involve measurement, and so, are "more complicated" than the second. Thus, the second property is the one usually chosen as the defining property of parallel lines in Euclidean geometry.<ref>{{harvnb|Wylie Jr.|1964|loc=pp. 92—94}}</ref> The other properties are then consequences of [[Euclid's Fifth Axiom|Euclid's Parallel Postulate]]. Another property that also involves measurement is that lines parallel to each other have the same [[gradient]] (slope). |

|||

====History==== |

|||

The definition of parallel lines as a pair of straight lines in a plane which do not meet appears as Definition 23 in Book I of [[Euclid's Elements]].<ref name=Euclid>{{harvnb|Heath|1956|loc=pp. 190–194}}</ref> Alternative definitions were discussed by other Greeks, often as part of an attempt to prove the [[parallel postulate]]. [[Proclus]] attributes a definition of parallel lines as equidistant lines to [[Posidonius]] and quotes [[Geminus]] in a similar vein. [[Simplicius of Cilicia|Simplicius]] also mentions Posidonius' definition as well as its modification by the philosopher Aganis.<ref name=Euclid /> |

|||

At the end of the nineteenth century, in England, Euclid's Elements was still the standard textbook in secondary schools. The traditional treatment of geometry was being pressured to change by the new developments in [[projective geometry]] and [[non-Euclidean geometry]], so several new textbooks for the teaching of geometry were written at this time. A major difference between these reform texts, both between themselves and between them and Euclid, is the treatment of parallel lines.<ref>{{harvnb|Richards|1988|loc=Chap. 4: Euclid and the English Schoolchild. pp. 161–200}}</ref> These reform texts were not without their critics and one of them, Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. [[Lewis Carroll]]), wrote a play, ''Euclid and His Modern Rivals'', in which these texts are lambasted.<ref>{{citation|first=Lewis|last=Carroll|title=Euclid and His Modern Rivals|date=2009|orig-year=1879|publisher=Barnes & Noble|isbn=978-1-4351-2348-9}}</ref> |

|||

One of the early reform textbooks was James Maurice Wilson's ''Elementary Geometry'' of 1868.<ref>{{harvnb|Wilson|1868}}</ref> Wilson based his definition of parallel lines on the [[primitive notion]] of ''direction''. According to [[Wilhelm Killing]]<ref>''Einführung in die Grundlagen der Geometrie, I'', p. 5</ref> the idea may be traced back to [[Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz|Leibniz]].<ref>{{harvnb|Heath|1956|loc= p. 194}}</ref> Wilson, without defining direction since it is a primitive, uses the term in other definitions such as his sixth definition, "Two straight lines that meet one another have different directions, and the difference of their directions is the ''angle'' between them." {{harvtxt|Wilson|1868|loc=p. 2}} In definition 15 he introduces parallel lines in this way; "Straight lines which have the ''same direction'', but are not parts of the same straight line, are called ''parallel lines''." {{harvtxt|Wilson|1868|loc=p. 12}} [[Augustus De Morgan]] reviewed this text and declared it a failure, primarily on the basis of this definition and the way Wilson used it to prove things about parallel lines. Dodgson also devotes a large section of his play (Act II, Scene VI § 1) to denouncing Wilson's treatment of parallels. Wilson edited this concept out of the third and higher editions of his text.<ref>{{harvnb|Richards|1988|loc=pp. 180–184}}</ref> |

|||

Other properties, proposed by other reformers, used as replacements for the definition of parallel lines, did not fare much better. The main difficulty, as pointed out by Dodgson, was that to use them in this way required additional axioms to be added to the system. The equidistant line definition of Posidonius, expounded by Francis Cuthbertson in his 1874 text ''Euclidean Geometry'' suffers from the problem that the points that are found at a fixed given distance on one side of a straight line must be shown to form a straight line. This can not be proved and must be assumed to be true.<ref>{{harvnb|Heath|1956|loc=p. 194}}</ref> The corresponding angles formed by a transversal property, used by W. D. Cooley in his 1860 text, ''The Elements of Geometry, simplified and explained'' requires a proof of the fact that if one transversal meets a pair of lines in congruent corresponding angles then all transversals must do so. Again, a new axiom is needed to justify this statement. |

|||

==== Construction ==== |

|||

The three properties above lead to three different methods of construction<ref>Only the third is a straightedge and compass construction, the first two are infinitary processes (they require an "infinite number of steps".)</ref> of parallel lines. |

|||

{{Clear|left}} |

|||

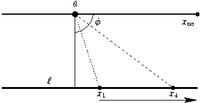

[[Image:Par-prob.png|thumb|left|250px|The problem: Draw a line through ''a'' parallel to ''l''.]] |

|||

{{Clear|left}} |

|||

<gallery widths="200px"> |

|||

image:Par-equi.png|Property 1: Line ''m'' has everywhere the same distance to line ''l''. |

|||

image:Par-para.png|Property 2: Take a random line through ''a'' that intersects ''l'' in ''x''. Move point ''x'' to infinity. |

|||

image:Par-perp.png|Property 3: Both ''l'' and ''m'' share a transversal line through ''a'' that intersect them at 90°. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==== Distance between two parallel lines ==== |

|||

{{Main|Distance between two lines}} |

|||

Because parallel lines in a Euclidean plane are [[equidistant]] there is a unique distance between the two parallel lines. Given the equations of two non-vertical, non-horizontal parallel lines, |

|||

:<math>y = mx+b_1\,</math> |

|||

:<math>y = mx+b_2\,,</math> |

|||

the distance between the two lines can be found by locating two points (one on each line) that lie on a common perpendicular to the parallel lines and calculating the distance between them. Since the lines have slope ''m'', a common perpendicular would have slope −1/''m'' and we can take the line with equation ''y'' = −''x''/''m'' as a common perpendicular. Solve the linear systems |

|||

:<math>\begin{cases} |

|||

y = mx+b_1 \\ |

|||

y = -x/m |

|||

\end{cases}</math> |

|||

and |

|||

:<math>\begin{cases} |

|||

y = mx+b_2 \\ |

|||

y = -x/m |

|||

\end{cases}</math> |

|||

to get the coordinates of the points. The solutions to the linear systems are the points |

|||

:<math>\left( x_1,y_1 \right)\ = \left( \frac{-b_1m}{m^2+1},\frac{b_1}{m^2+1} \right)\,</math> |

|||

and |

|||

:<math>\left( x_2,y_2 \right)\ = \left( \frac{-b_2m}{m^2+1},\frac{b_2}{m^2+1} \right).</math> |

|||

These formulas still give the correct point coordinates even if the parallel lines are horizontal (i.e., ''m'' = 0). The distance between the points is |

|||

:<math>d = \sqrt{\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2 + \left(y_2-y_1\right)^2} = \sqrt{\left(\frac{b_1m-b_2m}{m^2+1}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{b_2-b_1}{m^2+1}\right)^2}\,,</math> |

|||

which reduces to |

|||

:<math>d = \frac{|b_2-b_1|}{\sqrt{m^2+1}}\,.</math> |

|||

When the lines are given by the general form of the equation of a line (horizontal and vertical lines are included): |

|||

:<math>ax+by+c_1=0\,</math> |

|||

:<math>ax+by+c_2=0,\,</math> |

|||

their distance can be expressed as |

|||

:<math>d = \frac{|c_2-c_1|}{\sqrt {a^2+b^2}}.</math> |

|||

== Референце == |

|||

{{Reflist|refs= |

|||

<ref name="Kersey_1673">{{cite book |author-first=John |author-last=Kersey (the elder) |author-link=John Kersey the elder |title=Algebra |location=London |date=1673 |volume=Book IV |page=177}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Cajori_1928">{{cite book |author-first=Florian |author-last=Cajori |author-link=Florian Cajori |title=A History of Mathematical Notations - Notations in Elementary Mathematics |chapter=§ 184, § 359, § 368 |volume=1 |orig-year=September 1928 |publisher=[[Open court publishing company]] |location=Chicago, US |date=1993 |edition=two volumes in one unaltered reprint |pages=[https://archive.org/details/historyofmathema00cajo_0/page/193 193, 402–403, 411–412] |isbn=0-486-67766-4 |lccn=93-29211 |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofmathema00cajo_0/page/193 |access-date=2019-07-22 |quote=§359. […] ∥ for parallel occurs in [[William Oughtred|Oughtred]]'s ''Opuscula mathematica hactenus inedita'' (1677) [p. 197], a posthumous work (§ 184) […] §368. Signs for parallel lines. […] when [[Robert Recorde|Recorde]]'s sign of equality won its way upon the Continent, vertical lines came to be used for parallelism. We find ∥ for "parallel" in [[John Kersey the elder|Kersey]],[14] [[John Caswell|Caswell]], [[William Jones (mathematician)|Jones]],[15] Wilson,[16] [[William Emerson (mathematician)|Emerson]],[17] Kambly,[18] and the writers of the last fifty years who have been already quoted in connection with other pictographs. Before about 1875 it does not occur as often […] Hall and Stevens[1] use "par[1] or ∥" for parallel […] [14] [[John Kersey the elder|John Kersey]], ''Algebra'' (London, 1673), Book IV, p. 177. [15] [[William Jones (mathematician)|W. Jones]], ''Synopsis palmarioum matheseos'' (London, 1706). [16] John Wilson, ''Trigonometry'' (Edinburgh, 1714), characters explained. [17] [[William Emerson (mathematician)|W. Emerson]], ''Elements of Geometry'' (London, 1763), p. 4. [18] {{ill|Ludwig Kambly{{!}}L.<!-- Ludwig --> Kambly|de|Ludwig Kambly}}, ''Die Elementar-Mathematik'', Part 2: ''Planimetrie'', 43. edition (Breslau, 1876), p. 8. […] [1] H. S.<!-- Henry Sinclair --> Hall and F. H.<!-- Frederick Haller --> Stevens, ''Euclid's Elements'', Parts I and II (London, 1889), p. 10. […] }} [https://monoskop.org/images/2/21/Cajori_Florian_A_History_of_Mathematical_Notations_2_Vols.pdf]</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

== Литература == |

|||

У [[еуклидов простор|еуклидском простору]] -{'''R'''}-<sup>-{''n''}-</sup>, за два [[афини простор|афина потпростора]] -{''a''}-<sub>1</sub> + -{''V''}-<sub>1</sub> и -{''a''}-<sub>2</sub> + -{''V''}-<sub>2</sub> каже се да су паралелни ако је један од одговарајућих [[векторски простор|векторских потпростора]] -{''V''}-<sub>1</sub> и -{''V''}-<sub>2</sub> потпростор другог. |

|||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last = Heath |

|||

| first = Thomas L. |

|||

| author-link = T. L. Heath |

|||

| title = The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements |

|||

| edition = 2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] |

|||

| date = 1956 |

|||

| publisher = Dover Publications |

|||

| location = New York |

|||

}} |

|||

: (3 vols.): {{isbn|0-486-60088-2}} (vol. 1), {{isbn|0-486-60089-0}} (vol. 2), {{isbn|0-486-60090-4}} (vol. 3). Heath's authoritative translation plus extensive historical research and detailed commentary throughout the text. |

|||

* {{citation|last=Richards|first=Joan L.|author-link= Joan L. Richards |title=Mathematical Visions: The Pursuit of Geometry in Victorian England|date=1988|publisher=Academic Press|location=Boston|isbn=0-12-587445-6}} |

|||

* {{citation|first=James Maurice|last=Wilson|title=Elementary Geometry|edition=1st|date=1868|place=London|publisher=Macmillan and Co.}} |

|||

* {{citation|first=C. R.|last=Wylie Jr.|title=Foundations of Geometry|date=1964|publisher=McGraw–Hill}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last1 = Papadopoulos |

|||

| first1 = Athanase |

|||

| last2=Théret |

|||

|first2= Guillaume |

|||

| title = La théorie des parallèles de Johann Heinrich Lambert : Présentation, traduction et commentaires |

|||

| date = 2014 |

|||

| publisher = Collection Sciences dans l'histoire, Librairie Albert Blanchard |

|||

| place=Paris |

|||

|isbn=978-2-85367-266-5}} |

|||

* Nicholas M. Patrikalakis and Takashi Maekawa, ''Shape Interrogation for Computer Aided Design and Manufacturing'', Springer, 2002, {{ISBN|3540424547}}, 9783540424543, pp. 408. [https://books.google.com/books?id=qoxBeti5ySoC&dq=intersection&source=gbs_navlinks_s] |

|||

* A'Campo, Norbert and Papadopoulos, Athanase, (2012) ''Notes on hyperbolic geometry'', in: Strasbourg Master class on Geometry, pp. 1–182, IRMA Lectures in Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, Vol. 18, Zürich: European Mathematical Society (EMS), 461 pages, SBN {{isbn|978-3-03719-105-7}}, DOI 10.4171–105. |

|||

* [[Harold Scott MacDonald Coxeter|Coxeter, H. S. M.]], (1942) ''Non-Euclidean geometry'', University of Toronto Press, Toronto |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last=Fenchel |

|||

| first=Werner |author-link=Werner Fenchel |

|||

| title=Elementary geometry in hyperbolic space |

|||

| series=De Gruyter Studies in mathematics |

|||

| volume=11 |

|||

| publisher=Walter de Gruyter & Co. |

|||

| location=Berlin-New York |

|||

| year=1989 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last= Fenchel |

|||

| first=Werner |author-link=Werner Fenchel |

|||

|author2=[[Jakob Nielsen (mathematician)|Nielsen, Jakob]] |editor=Asmus L. Schmidt |

|||

| title=Discontinuous groups of isometries in the hyperbolic plane |

|||

| series=De Gruyter Studies in mathematics |

|||

| volume=29 |

|||

| publisher=Walter de Gruyter & Co. |

|||

| location=Berlin |

|||

| year=2003 |

|||

}} |

|||

* Lobachevsky, Nikolai I., (2010) ''Pangeometry'', Edited and translated by Athanase Papadopoulos, Heritage of European Mathematics, Vol. 4. Zürich: European Mathematical Society (EMS). xii, 310~p, {{isbn|978-3-03719-087-6}}/hbk |

|||

* [[John Milnor|Milnor, John W.]], (1982) ''[http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.bams/1183548588 Hyperbolic geometry: The first 150 years]'', Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) Volume 6, Number 1, pp. 9–24. |

|||

* Reynolds, William F., (1993) ''Hyperbolic Geometry on a Hyperboloid'', [[American Mathematical Monthly]] 100:442–455. |

|||

* {{Cite book | last1=Stillwell | first1=John | author1-link=John Stillwell | title=Sources of hyperbolic geometry | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZQjBXxxQsucC | publisher=[[American Mathematical Society]] | location=Providence, R.I. | series=History of Mathematics | isbn=978-0-8218-0529-9 | year=1996 | volume=10 | mr=1402697}} |

|||

* Samuels, David, (March 2006) ''Knit Theory'' Discover Magazine, volume 27, Number 3. |

|||

* James W. Anderson, ''Hyperbolic Geometry'', Springer 2005, {{isbn|1-85233-934-9}} |

|||

* James W. Cannon, William J. Floyd, Richard Kenyon, and Walter R. Parry (1997) ''[http://www.msri.org/communications/books/Book31/files/cannon.pdf Hyperbolic Geometry]'', MSRI Publications, volume 31. |

|||

* {{citation|first=Bruce E.|last=Meserve|title=Fundamental Concepts of Geometry|date=1983|orig-year=1959|publisher=Dover|isbn=0-486-63415-9}} |

|||

* {{citation|first=Athanase|last=Papadopoulos|title=Euler, la géométrie sphérique et le calcul des variations. In: Leonhard Euler : Mathématicien, physicien et théoricien de la musique (dir. X. Hascher et A. Papadopoulos)|date=2015|publisher=CNRS Editions, Paris|isbn=978-2-271-08331-9}} |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Van Brummelen|first=Glen|author-link=Glen van Brummelen|title=Heavenly Mathematics: The Forgotten Art of Spherical Trigonometry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0BCCz8Sx5wkC|access-date=31 December 2014|year=2013|publisher=[[Princeton University Press]]|isbn=9780691148922}} |

|||

* [[Roshdi Rashed]] and Athanase Papadopoulos (2017) ''Menelaus' Spherics: Early Translation and al-Mahani'/alHarawi's version. Critical edition of Menelaus' Spherics from the Arabic manuscripts, with historical and mathematical commentaries'', [[De Gruyter]] Series: Scientia Graeco-Arabica 21 {{ISBN|978-3-11-057142-4}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

У геометријском простору тачака у којем је уведен појам [[бесконачност|бесконачно]] далеких тачака, два геометријска објекта су паралелна уколико се секу у бесконачно далекој тачки. |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

|||

{{клица-математика}} |

|||

{{Commons category-lat|Parallel (geometry)}} |

|||

* [http://www.mathopenref.com/constparallel.html Constructing a parallel line through a given point with compass and straightedge] |

|||

{{нормативна контрола}} |

{{нормативна контрола}} |

||

Верзија на датум 16. јул 2022. у 21:12

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Паралелност у геометрији представља однос између два геометријска објекта. Примери дефинисања паралелности у еуклидској геометрији су:

- Две праве су паралелне уколико се налазе у једној равни и не секу се.

- Права је паралелна са равни, уколико са њом нема пресечних тачака. (еуклидски простор)

- Две различите равни су паралелне уколико се не секу. (еуклидски простор)

У тродимензионом простору треба разликовати појам паралелности и мимоилажења. Уколико две праве не леже у истој равни и не секу се, онда су исте мимоилазне а не паралелне. По сличном концепту постоји и појам мимоилазних равни у еуклидским просторима већих димензија. У еуклидском простору Rn, за два афина потпростора a1 + V1 и a2 + V2 каже се да су паралелни ако је један од одговарајућих векторских потпростора V1 и V2 потпростор другог. У геометријском простору тачака у којем је уведен појам бесконачно далеких тачака, два геометријска објекта су паралелна уколико се секу у бесконачно далекој тачки.

Parallel lines are the subject of Euclid's parallel postulate.[1] Parallelism is primarily a property of affine geometries and Euclidean geometry is a special instance of this type of geometry. In some other geometries, such as hyperbolic geometry, lines can have analogous properties that are referred to as parallelism.

Симбол

The parallel symbol is .[2][3] For example, indicates that line AB is parallel to line CD.

In the Unicode character set, the "parallel" and "not parallel" signs have codepoints U+2225 (∥) and U+2226 (∦), respectively. In addition, U+22D5 (⋕) represents the relation "equal and parallel to".[4]

The same symbol is used for a binary function in electrical engineering (the parallel operator). It is distinct from the double-vertical-line brackets that indicate a norm, as well as from the logical or operator (||) in several programming languages.

Еуклидски паралелизам

Two lines in a plane

Conditions for parallelism

Given parallel straight lines l and m in Euclidean space, the following properties are equivalent:

- Every point on line m is located at exactly the same (minimum) distance from line l (equidistant lines).

- Line m is in the same plane as line l but does not intersect l (recall that lines extend to infinity in either direction).

- When lines m and l are both intersected by a third straight line (a transversal) in the same plane, the corresponding angles of intersection with the transversal are congruent.

Since these are equivalent properties, any one of them could be taken as the definition of parallel lines in Euclidean space, but the first and third properties involve measurement, and so, are "more complicated" than the second. Thus, the second property is the one usually chosen as the defining property of parallel lines in Euclidean geometry.[5] The other properties are then consequences of Euclid's Parallel Postulate. Another property that also involves measurement is that lines parallel to each other have the same gradient (slope).

History

The definition of parallel lines as a pair of straight lines in a plane which do not meet appears as Definition 23 in Book I of Euclid's Elements.[6] Alternative definitions were discussed by other Greeks, often as part of an attempt to prove the parallel postulate. Proclus attributes a definition of parallel lines as equidistant lines to Posidonius and quotes Geminus in a similar vein. Simplicius also mentions Posidonius' definition as well as its modification by the philosopher Aganis.[6]

At the end of the nineteenth century, in England, Euclid's Elements was still the standard textbook in secondary schools. The traditional treatment of geometry was being pressured to change by the new developments in projective geometry and non-Euclidean geometry, so several new textbooks for the teaching of geometry were written at this time. A major difference between these reform texts, both between themselves and between them and Euclid, is the treatment of parallel lines.[7] These reform texts were not without their critics and one of them, Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll), wrote a play, Euclid and His Modern Rivals, in which these texts are lambasted.[8]

One of the early reform textbooks was James Maurice Wilson's Elementary Geometry of 1868.[9] Wilson based his definition of parallel lines on the primitive notion of direction. According to Wilhelm Killing[10] the idea may be traced back to Leibniz.[11] Wilson, without defining direction since it is a primitive, uses the term in other definitions such as his sixth definition, "Two straight lines that meet one another have different directions, and the difference of their directions is the angle between them." Wilson (1868, p. 2) In definition 15 he introduces parallel lines in this way; "Straight lines which have the same direction, but are not parts of the same straight line, are called parallel lines." Wilson (1868, p. 12) Augustus De Morgan reviewed this text and declared it a failure, primarily on the basis of this definition and the way Wilson used it to prove things about parallel lines. Dodgson also devotes a large section of his play (Act II, Scene VI § 1) to denouncing Wilson's treatment of parallels. Wilson edited this concept out of the third and higher editions of his text.[12]

Other properties, proposed by other reformers, used as replacements for the definition of parallel lines, did not fare much better. The main difficulty, as pointed out by Dodgson, was that to use them in this way required additional axioms to be added to the system. The equidistant line definition of Posidonius, expounded by Francis Cuthbertson in his 1874 text Euclidean Geometry suffers from the problem that the points that are found at a fixed given distance on one side of a straight line must be shown to form a straight line. This can not be proved and must be assumed to be true.[13] The corresponding angles formed by a transversal property, used by W. D. Cooley in his 1860 text, The Elements of Geometry, simplified and explained requires a proof of the fact that if one transversal meets a pair of lines in congruent corresponding angles then all transversals must do so. Again, a new axiom is needed to justify this statement.

Construction

The three properties above lead to three different methods of construction[14] of parallel lines.

-

Property 1: Line m has everywhere the same distance to line l.

-

Property 2: Take a random line through a that intersects l in x. Move point x to infinity.

-

Property 3: Both l and m share a transversal line through a that intersect them at 90°.

Distance between two parallel lines

Because parallel lines in a Euclidean plane are equidistant there is a unique distance between the two parallel lines. Given the equations of two non-vertical, non-horizontal parallel lines,

the distance between the two lines can be found by locating two points (one on each line) that lie on a common perpendicular to the parallel lines and calculating the distance between them. Since the lines have slope m, a common perpendicular would have slope −1/m and we can take the line with equation y = −x/m as a common perpendicular. Solve the linear systems

and

to get the coordinates of the points. The solutions to the linear systems are the points

and

These formulas still give the correct point coordinates even if the parallel lines are horizontal (i.e., m = 0). The distance between the points is

which reduces to

When the lines are given by the general form of the equation of a line (horizontal and vertical lines are included):

their distance can be expressed as

Референце

- ^ Although this postulate only refers to when lines meet, it is needed to prove the uniqueness of parallel lines in the sense of Playfair's axiom.

- ^ Kersey (the elder), John (1673). Algebra. Book IV. London. стр. 177.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1993) [September 1928]. „§ 184, § 359, § 368”. A History of Mathematical Notations - Notations in Elementary Mathematics. 1 (two volumes in one unaltered reprint изд.). Chicago, US: Open court publishing company. стр. 193, 402–403, 411–412. ISBN 0-486-67766-4. LCCN 93-29211. Приступљено 2019-07-22. „§359. […] ∥ for parallel occurs in Oughtred's Opuscula mathematica hactenus inedita (1677) [p. 197], a posthumous work (§ 184) […] §368. Signs for parallel lines. […] when Recorde's sign of equality won its way upon the Continent, vertical lines came to be used for parallelism. We find ∥ for "parallel" in Kersey,[14] Caswell, Jones,[15] Wilson,[16] Emerson,[17] Kambly,[18] and the writers of the last fifty years who have been already quoted in connection with other pictographs. Before about 1875 it does not occur as often […] Hall and Stevens[1] use "par[1] or ∥" for parallel […] [14] John Kersey, Algebra (London, 1673), Book IV, p. 177. [15] W. Jones, Synopsis palmarioum matheseos (London, 1706). [16] John Wilson, Trigonometry (Edinburgh, 1714), characters explained. [17] W. Emerson, Elements of Geometry (London, 1763), p. 4. [18] de, Die Elementar-Mathematik, Part 2: Planimetrie, 43. edition (Breslau, 1876), p. 8. […] [1] H. S. Hall and F. H. Stevens, Euclid's Elements, Parts I and II (London, 1889), p. 10. […]” [1]

- ^ „Mathematical Operators – Unicode Consortium” (PDF). Приступљено 2013-04-21.

- ^ Wylie Jr. 1964, pp. 92—94

- ^ а б Heath 1956, pp. 190–194

- ^ Richards 1988, Chap. 4: Euclid and the English Schoolchild. pp. 161–200

- ^ Carroll, Lewis (2009) [1879], Euclid and His Modern Rivals, Barnes & Noble, ISBN 978-1-4351-2348-9

- ^ Wilson 1868

- ^ Einführung in die Grundlagen der Geometrie, I, p. 5

- ^ Heath 1956, p. 194

- ^ Richards 1988, pp. 180–184

- ^ Heath 1956, p. 194

- ^ Only the third is a straightedge and compass construction, the first two are infinitary processes (they require an "infinite number of steps".)

Литература

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956), The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] изд.), New York: Dover Publications

- (3 vols.): ISBN 0-486-60088-2 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-486-60089-0 (vol. 2), ISBN 0-486-60090-4 (vol. 3). Heath's authoritative translation plus extensive historical research and detailed commentary throughout the text.

- Richards, Joan L. (1988), Mathematical Visions: The Pursuit of Geometry in Victorian England, Boston: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-587445-6

- Wilson, James Maurice (1868), Elementary Geometry (1st изд.), London: Macmillan and Co.

- Wylie Jr., C. R. (1964), Foundations of Geometry, McGraw–Hill

- Papadopoulos, Athanase; Théret, Guillaume (2014), La théorie des parallèles de Johann Heinrich Lambert : Présentation, traduction et commentaires, Paris: Collection Sciences dans l'histoire, Librairie Albert Blanchard, ISBN 978-2-85367-266-5

- Nicholas M. Patrikalakis and Takashi Maekawa, Shape Interrogation for Computer Aided Design and Manufacturing, Springer, 2002, ISBN 3540424547, 9783540424543, pp. 408. [2]

- A'Campo, Norbert and Papadopoulos, Athanase, (2012) Notes on hyperbolic geometry, in: Strasbourg Master class on Geometry, pp. 1–182, IRMA Lectures in Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, Vol. 18, Zürich: European Mathematical Society (EMS), 461 pages, SBN ISBN 978-3-03719-105-7, DOI 10.4171–105.

- Coxeter, H. S. M., (1942) Non-Euclidean geometry, University of Toronto Press, Toronto

- Fenchel, Werner (1989). Elementary geometry in hyperbolic space. De Gruyter Studies in mathematics. 11. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Fenchel, Werner; Nielsen, Jakob (2003). Asmus L. Schmidt, ур. Discontinuous groups of isometries in the hyperbolic plane. De Gruyter Studies in mathematics. 29. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Lobachevsky, Nikolai I., (2010) Pangeometry, Edited and translated by Athanase Papadopoulos, Heritage of European Mathematics, Vol. 4. Zürich: European Mathematical Society (EMS). xii, 310~p, ISBN 978-3-03719-087-6/hbk

- Milnor, John W., (1982) Hyperbolic geometry: The first 150 years, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) Volume 6, Number 1, pp. 9–24.

- Reynolds, William F., (1993) Hyperbolic Geometry on a Hyperboloid, American Mathematical Monthly 100:442–455.

- Stillwell, John (1996). Sources of hyperbolic geometry. History of Mathematics. 10. Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-0529-9. MR 1402697.

- Samuels, David, (March 2006) Knit Theory Discover Magazine, volume 27, Number 3.

- James W. Anderson, Hyperbolic Geometry, Springer 2005, ISBN 1-85233-934-9

- James W. Cannon, William J. Floyd, Richard Kenyon, and Walter R. Parry (1997) Hyperbolic Geometry, MSRI Publications, volume 31.

- Meserve, Bruce E. (1983) [1959], Fundamental Concepts of Geometry, Dover, ISBN 0-486-63415-9

- Papadopoulos, Athanase (2015), Euler, la géométrie sphérique et le calcul des variations. In: Leonhard Euler : Mathématicien, physicien et théoricien de la musique (dir. X. Hascher et A. Papadopoulos), CNRS Editions, Paris, ISBN 978-2-271-08331-9

- Van Brummelen, Glen (2013). Heavenly Mathematics: The Forgotten Art of Spherical Trigonometry. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691148922. Приступљено 31. 12. 2014.

- Roshdi Rashed and Athanase Papadopoulos (2017) Menelaus' Spherics: Early Translation and al-Mahani'/alHarawi's version. Critical edition of Menelaus' Spherics from the Arabic manuscripts, with historical and mathematical commentaries, De Gruyter Series: Scientia Graeco-Arabica 21 ISBN 978-3-11-057142-4