Пет династија и десет краљевстава — разлика између измена

. |

|||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{Short description|Период кинеске историје 907–979}} |

|||

{{Потребна транскрипција}} |

|||

[[Датотека:Five Dynasties Ten Kingdoms 923 CE.png|мини|Династија Касни Лијанг (жуто) и тадашња кинеска краљевства]] |

[[Датотека:Five Dynasties Ten Kingdoms 923 CE.png|мини|Династија Касни Лијанг (жуто) и тадашња кинеска краљевства]] |

||

| ⚫ | '''Пет династија и десет краљевстава''' ({{јез-кин-туп|т=五代十國|у=五代十国|п=Wǔdài Shíguó}}) је израз који се користи за турбулентни период [[Историја Кине|кинеске историје]] који је започео 907. падом [[династија Танг|династије Танг]], а завршио успоставом [[династија Сунг|династије Сунг]] 960. године, односно формалном обновом политичког јединства [[Кинеско царство|царске Кине]] под њеном влашћу 979. Име је добила по пет династија које су представљале формалне насљеднике династије Танг те се брзо измијениле на пријестољу од 907. до 960. као и по 10 одметнутих држава (чији је број у стварности био већи од 12). Иако је на његовом крају Кина изашла као обновљена политичка цјелина, неки од ранијих територија на сјеверу су потпали под власт тада основане [[Китан (народ)|китанске]] [[династија Љао|династије Љао]]. |

||

{{историја Кине}} |

{{историја Кине}} |

||

| ⚫ | '''Пет династија и десет краљевстава''' ({{јез-кин-туп|т=五代十國|у=五代十国|п=Wǔdài Shíguó}}) је израз који се користи за турбулентни период [[Историја Кине|кинеске историје]] који је започео 907. падом [[династија Танг|династије Танг]], а завршио успоставом [[династија Сунг|династије Сунг]] 960. године, односно формалном обновом политичког јединства [[Кинеско царство|царске Кине]] под њеном влашћу 979. Име је добила по пет династија које су представљале формалне насљеднике династије Танг те се брзо измијениле на пријестољу од 907. до 960. као и по 10 одметнутих држава (чији је број у стварности био већи од 12). Иако је на његовом крају Кина изашла као обновљена политичка цјелина, неки од ранијих територија на сјеверу су потпали под власт тада основане [[Китан (народ)|китанске]] [[династија Љао|династије Љао]]. |

||

'''Пет династија:''' |

'''Пет династија:''' |

||

* [[Династија Каснији Лианг]] (1. јун 907–923) |

* [[Династија Каснији Лианг]] (1. јун 907–923) |

||

| Ред 13: | Ред 15: | ||

Остале државе/династије/режими: [[Yan (Pet dinastija)|Yan]], [[Qi (Pet dinastija)|Qi]], [[Zhao (Pet dinastija)|Zhao]], [[Yiwu Jiedushi]], [[Dingnan Jiedushi]], [[Wuping Jiedushi]], [[Qingyuan Jiedushi]], [[Yin (Deset kraljevstava)|Yin]], [[Zhangye|Ganzhou]], [[Dunhuang|Shazhou]], [[Wuwei (Gansu)|Liangzhou]]. |

Остале државе/династије/режими: [[Yan (Pet dinastija)|Yan]], [[Qi (Pet dinastija)|Qi]], [[Zhao (Pet dinastija)|Zhao]], [[Yiwu Jiedushi]], [[Dingnan Jiedushi]], [[Wuping Jiedushi]], [[Qingyuan Jiedushi]], [[Yin (Deset kraljevstava)|Yin]], [[Zhangye|Ganzhou]], [[Dunhuang|Shazhou]], [[Wuwei (Gansu)|Liangzhou]]. |

||

== Позадина == |

|||

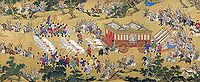

[[Датотека:五代-北宋 佚名 乞巧圖 軸-Palace banquet MET DP251118.jpg|thumb|left|250п|''Palace Banquet'' by Anonymous, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period]] |

|||

{{рут}} |

|||

Towards the end of the Tang dynasty, the imperial government granted increased powers to the ''[[jiedushi]]'', the regional military governors. The [[An Lushan]] (755–763) and [[Huang Chao]] rebellions weakened the imperial government, and by the early 10th century the ''jiedushi'' commanded ''de facto'' independence from its authority. In the last decades of the Tang dynasty, they were not even appointed by the central court any more, but developed hereditary systems, from father to son or from patron to protégé. They had their own armies rivaling the "palace armies" and amassed huge wealth, as testified by their sumptuous tombs.<ref name=Davis>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CMkzCgAAQBAJ|title=Historical Records of the Five Dynasties|pages=lv–lxv|author=Xiu Ouyang|publisher=Columbia University Press|year=2004|isbn=9780231128278|translator=Richard L. Davis}} The information was taken from Richard L. Davis's introduction.</ref> Due to the decline of Tang central authority after the An Lushan Rebellion, there was growing tendency to superimpose large regional administrations over the old districts and prefectures that had been used since the [[Qin dynasty]] (221–206 BC). These administrations, known as circuit commissions, would become the boundaries of the later Southern regimes; many circuit commissioners became the emperors or kings of these states.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Robert M. Hartwell |title=Demographic, Political, and Social Transformations of China, 750–1550 |journal=Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies |date=1982 |volume=42 |issue=2 |page=397}}</ref> |

|||

===North=== |

|||

According to Nicholas Tackett, the [[Three Fanzhen of Hebei|three provinces of Hebei]]: Chengde, Youzhou, Weibo, were able to maintain much greater autonomy from the central government in the aftermath of the An Lushan rebellion. With their administration under local military control, these provinces never submitted tax revenues and governorships lapsed into hereditary succession. They engaged in occasional war with the central government, or against each other, and Youzhou seemed to conduct its own foreign policy. This meant that the culture of these northeastern provinces started diverging from the capital. Many of the elites in post-Tang China, including the future emperors of the Song dynasty, came from this region.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Nicolas Tackett |title=The Destruction of the Medieval Chinese Aristocracy |date=2014 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=9780674492059 |pages=151–184}}</ref> |

|||

The administrations of the Five Dynasties and the early Song dynasty shared a pattern of being disproportionately drawn from the families of military governors in northern and northwestern China ([[Hebei]], [[Shanxi]], [[Shaanxi]]), their personal staff, and the bureaucrats who served in the capitals of the Five dynasties. These families had risen to prominence due to the unraveling of central authority after the An Lushan Rebellion, despite lacking esteemed ancestry.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Robert M. Hartwell |title=Demographic, Political, and Social Transformations of China, 750–1550 |journal=Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies |date=1982 |volume=42 |issue=2 |pages=405–408}}</ref> The historian [[Deng Xiaonan]] argued that many of these military families, including the [[House of Zhao|Song imperial family]], were of mixed Han Chinese-Turkic-[[Kumo Xi]] ancestry.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Nicolas Tackett |title=The Origins of the Chinese Nation |date=2017 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=University of California, Berkeley |isbn=978-1-316-64748-6 |page=100}}</ref> |

|||

The Southern regimes generally had more stable and effective government during this period.<ref>Eberhard, Wolfram, ''A History of China'' (1977), "Chapter IX: The Epoch of the Second Division of China."</ref> The Qing historian [[Wang Fuzhi]] (1619–1692) wrote that this period can be compared to the earlier [[Warring States period]] of ancient China, remarking that none of the rulers could be described as "[[Son of Heaven]]". These rulers, despite claiming the status of [[Emperor of China|emperor]], sometimes dealt with each other on terms of diplomatic equality out of pragmatic concern. This concept of "sharing the Mandate of Heaven" as "sibling states" was the result of the brief balance of power. After the reunification of China by the Song dynasty, the Song embarked on a special effort to denounce such arrangements.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Nicolas Tackett |title=The Origins of the Chinese Nation |date=2017 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=University of California, Berkeley |isbn=978-1-316-64748-6 |pages=72–73}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Wang, Hongjie |title=Power and politics in tenth-century China : the Former Shu regime |date=2011 |publisher=Cambria Press |location=Amherst, NY |isbn=978-1-60497-764-6 |pages=2, 5–6, 8, 11–12, 115, 118, 122, 233, 247, 248}}</ref> |

|||

===South=== |

|||

Even the rulers of the Southern states were almost all military leaders from the north with their key officers and elite forces also hailing from the north, since the bulk of the Tang army was based in the north.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wang, Hongjie |title=Power and politics in tenth-century China : the Former Shu regime |date=2011 |publisher=Cambria Press |location=Amherst, NY |isbn=978-1-60497-764-6 |pages=82}}</ref> The founders of Wu and Former Shu were 'rogues' from [[Huainan]] and [[Xuchang]] respectively, the founder of Min was a minor government staffer from Huainan, the founder of Wuyue was a 'rogue' from [[Hangzhou]], the founder of Chu was (according to one source) a carpenter from Xuchang, the founder of Jingnan was a slave from [[Shanzhou]] and the founder of Southern Han was a southern tribal chief.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Peter Lorge |title=Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms |date=2011 |publisher=The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press |pages=51–78}}</ref> The Southern kingdoms were founded by men of low social status who rose up through superior military ability, who were later scorned as "bandits" by future scholars. However, once established, these rulers took great pains to portray themselves as promoters of culture and economic development so as to legitimise their rule; many wooed former Tang courtiers to help administer their states.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Benjamin Brose |title=Patrons and Patriarchs: Regional Rulers and Chan Monks during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms |date=2015 |publisher=University of Hawaii Press |isbn=978-0824857240 |pages=20–21}}</ref> |

|||

The economies of each of the southern regions had prospered in the late Tang. Guangdong and Fujian were the sites of important port cities trading exotic goods, the middle Yangtze and Sichuan were centres of tea and porcelain production, and the Yangtze delta was a center of extremely high agricultural production and an entrepot for the other regions. The regions were economically interdependent. Sui and Tang policies, while paying little attention to developing the south, gave the south room to innovate free of tight administrative controls. The dominant northern officials had been unwilling to serve in the south during the Tang, and so southerners were recruited by the Tang to serve in a local capacity under the "Southern Selection" supplemental system. These southern officials became the administrative core of the Ten Kingdoms and later dominated the bureaucracy by the mid-Song.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hugh Clark |title=China during the Tang-Song Interregnum, 878–978: New Approaches to the Southern Kingdoms |date=2021 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781000426397 |pages=101–103}}</ref> |

|||

== Извори == |

== Извори == |

||

| Ред 18: | Ред 38: | ||

== Литература == |

== Литература == |

||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Michael Szonyi |title=A Companion to Chinese History |date=2017 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Ltd |location=Hoboken, NJ |isbn=9781118624548 |pages= }} |

|||

* {{Cite book|title=China's Southern Tang Dynasty (937-976)|author=Kurz, Johannes L.|publisher=Routledge|year=2011|isbn=978-0-415-45496-4|ref=harv}} |

* {{Cite book|title=China's Southern Tang Dynasty (937-976)|author=Kurz, Johannes L.|publisher=Routledge|year=2011|isbn=978-0-415-45496-4|ref=harv}} |

||

* {{cite book|title=From Warhorses to Ploughshares: The Later Tang Reign of Emperor Mingzong|author=Davis, Richard L.|publisher=Hong Kong University Press|year=2015|isbn=9789888208104}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=A Portrait of Five Dynasties China: From the Memoirs of Wang Renyu (880-956)|author=Dudbridge, Glen|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=2013|isbn=978-0199670680}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Ten States, Five Dynasties, One Great Emperor: How Emperor Taizu Unified China in the Song Dynasty|author=Hung, Hing Ming|publisher=Algora Publishing|year=2014|isbn=978-1-62894-072-5}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms|editor=Lorge, Peter|publisher=The Chinese University Press |year=2011|isbn=978-9629964184}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Empire of Min: A South China Kingdom of the Tenth Century|author=Schafer, Edward H.|author-link=Edward H. Schafer|publisher=[[Tuttle Publishing]]|year=1954}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=The Structure of Power in North China During the Five Dynasties|author=Wang Gungwu|author-link=Wang Gungwu|publisher=Stanford University Press|year=1963}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Power and Politics in Tenth-Century China: The Former Shu Regime|author=Wang Hongjie|publisher=[[Cambria Press]]|year=2011|isbn=978-1604977646}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last = Mote |first = F.W. |title = Imperial China: 900–1800 |publisher = Harvard University Press |year = 1999 |ISBN = 0-674-01212-7 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal|first=Christopher P.|last= Atwood|title=The Notion of Tribe in Medieval China: Ouyang Xiu and the Shatup Dynastic Myth|journal= Miscellanea Asiatica|year= 2010|url= https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/16/|pages= 610–613}} |

|||

* {{cite thesis|type= PhD|last= Barenghi|first= Maddalena|title= Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923–936) and Later Jin (936–947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh century Sources|date= 2014|url= https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/20635/|page= 3-4}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Ouyang |first=Xiu |translator = Richard L. Davis |title = Historical Records of the Five Dynasties|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R0QpslzUi50C&pg=PA76|date=5 April 2004 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn = 978-0-231-50228-3 |pages=76–}} |

|||

* {{cite book |first = Chang Woei |last = Ong |title = Men of Letters Within the Passes: Guanzhong Literati in Chinese History, 907–1911 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=w5_ZAAAAMAAJ&q=wujing+boshi+descendant|year=2008|publisher=Harvard University Asia Center|isbn=978-0-674-03170-8 |page = 29 }} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Chen|first=Yuan Julian|title="Legitimation Discourse and the Theory of the Five Elements in Imperial China." Journal of Song-Yuan Studies 44 (2014): 325–364.|journal=Journal of Song-Yuan Studies|year=2014 |volume=44 |issue=1 |page=325 |doi=10.1353/sys.2014.0000|s2cid=147099574|url=https://www.academia.edu/23276848|language=en}} |

|||

* {{Cite wikisource|title=Qīngyì lù|wslink=清異錄|wslanguage=zh|last=Gu|first=Tao|author-mask=Tao Gu 陶穀|year=n.d.e}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Zīzhì Tōngjiàn|wslink=資治通鑑|wslanguage=zh|last=Guang|first=Sima|author-link=Sima Guang|year=1084}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Sìkù Quánshū Zǒngmù Tíyào|wslink=四庫全書總目提要|wslanguage=zh|last=Ji|first=Yun|author-link=Ji Yun|year=1798}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Xù Zīzhì Tōngjiàn Chángbiān|wslink=續資治通鑑長編|wslanguage=zh|last=Li|first=Tao|author-link=Li Tao (historian)|year=1193}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Lù Shì Nán Táng Shū|wslink=陸氏南唐書|wslanguage=zh|last=Lu |first=You|author-mask=Lu, You 陸游|year=1184}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Mǎ Shì Nán Táng Shū|wslink=馬氏南唐書 (四部叢刊本)|wslanguage=zh|first=Ma|last=Ling|author-mask=Ling, Ma 馬令|date=n.d.e}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Wǔdài Shǐjì|wslink=新五代史|wslanguage=zh|last=Ouyang|first=Xiu|author-link=Ouyang Xiu|year=1073}} |

|||

* {{Cite wikisource|title=Ōuyáng xiū jí|wslink=歐陽修集 |

|||

|wslanguage=zh|last=Ouyang|first=Xiu|author-link=Ouyang Xiu|year=n.d.e}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Shíguó chūnqiūn|wslink=十國春秋|wslanguage=zh|last=Renchen|first=Wu|author-link=Wu Renchen|date=n.d.e}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Sòng Shǐ|wslink=宋史|wslanguage=zh|last=Toqto'a|first=|author-link=Toqto'a (Yuan dynasty)|year=1343}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Yù Hú Qīng Huà|wslink=玉壺清話|wslanguage=zh|last=Wenying|first=|author-link=Wenying|year=1078}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Jiù Wǔdài Shǐ|wslink=舊五代史|wslanguage=zh|last=Xue|first=Juzheng|author-link=Xue Juzheng|year=974}} |

|||

* {{cite wikisource|title=Nán Táng Jìn Shì|wslink=南唐近事|wslanguage=zh|last=Zheng|first=Wenbao|author-mask=Zheng, Wenbao 鄭文寶|year=978}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Brose|first=Benjamin|title=Patrons and Patriarchs : Regional Rulers and Chan monks during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms|publisher=University of Hawaii Press|year=2015|isbn=978-0-8248-5381-5|series=Studies in East Asian Buddhism|volume=25|location=Honolulu|pages=}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Clark|first=Hugh R.|title=The Sinitic Encounter in Southeast China through the First Millennium CE|publisher=University of Hawaii Press|year=2016|isbn=978-0-8248-5160-6|location=Honolulu|pages=}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Clark|first=Hugh R.|title=The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2009|isbn=978-0-521-81248-1|editor-last=Twitchett|editor-first=Denis|editor-link=Denis Twitchett|volume=5|series=[[The Cambridge History of China]]|location=New York|pages=133–205|chapter=The Southern Kingdoms between the T’ang and the Sung, 907–979|editor-last2=Smith|editor-first2=Paul J.}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last1=Fu|first1=Chonglan|title=Introduction to the Urban History of China|last2=Cao|first2=Wenming|publisher=[[Palgrave Macmillan]]|year=2019|isbn=978-981-13-8206-2|series=China Connections|location=London|pages=|translator-last=Zhang|translator-first=Qinggang|doi=10.1007/978-981-13-8207-9}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Hartill|first=David|title=Cast Chinese coins|publisher=Trafford Publishing|year=2005|isbn=978-1412054669|location=Trafford|pages=}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Hay|first=Jonathan|title=Tenth-century China and Beyond: Art and Visual Culture in a Multi-centered Age|publisher=The Center for the Art of East Asia, University of Chicago|year=2012|isbn=978-1588861153|editor-last=Hung|editor-first=Wu|location=Chicago|pages=285–318|chapter=Tenth-Century Painting before Song Taizong’s Reign: A Macrohistorical View}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Kurz|first=Johannes|title=Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms|publisher=China University Press|year=2011b|isbn=978-9629964184|editor-last=Lorge|editor-first=Peter|location=Hong Kong|pages=79–98|chapter=Han Xizai (902–970): An Eccentric Life in Exciting Times}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Kurz|first=Johannes|chapter=The Yangzi in the Negotiations between the Southern Tang and Its Northern Neighbors (Mid-Tenth Century)|title=China and Her Neighbours: Borders, Visions of the Other, Foreign Policy 10th to 19th Century|publisher=[[Harrassowitz]]|year=1997|isbn=3447039426|editor-last=Dabringhaus|editor-first=Sabine|series=South China and maritime Asia|volume=6|location=Wiesbaden|pages=|editor-last2=Ptak|editor-first2=Roderich|editor-last3=Teschke|editor-first3=Richard}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Lorge|first=Peter|title=Debating War in Chinese History|publisher=Brill|year=2013|isbn=978-90-04-22372-1|editor-last=Lorge|editor-first=Peter A.|location=Leiden and New York|pages=107–140|chapter=Fighting Against Empire: Resistance to the Later Zhou and Song Conquest of China}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Lorge|first=Peter A.|title=War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795|publisher=Routledge|year=2005|isbn=0-415-31690-1|location=London and New York|pages=}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Imperial China (900-1800)|last=Mote|first=F. W.|publisher=Harvard University Press|year=1999|location=|pages=|isbn=0674012127}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Standen|first=Naomi|title=The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2009|isbn=978-0-521-81248-1|editor-last=Twitchett|editor-first=Denis|editor-link=Denis Twitchett|volume=5|series=[[The Cambridge History of China]]|location=New York|pages=38–132|chapter=The Five Dynasties|editor-last2=Smith|editor-first2=Paul J.}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last1=Twitchett|first1=Denis|title=Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368|last2=Tietze|first2=Klaus-Peter|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1994|isbn=0-521-24331-9|editor-last=Franke|editor-first=Herbert|volume=6|series=[[The Cambridge History of China]]|location=New York|pages=43–153|chapter=The Liao|author-link=Denis Twitchett|editor-last2=Twitchett|editor-first2=Denis}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Worthy|first=Edmund H.|title=China among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries|publisher=University of California Press|year=1983|isbn=0520043839|editor-last=Rossabi|editor-first=Morris|location=Berkley and Los Angeles|pages=17–46|chapter=Diplomacy for Survival: Domestic and Foreign Relations of Wu Yüeh, 907-978}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=The Four Seasons of Tang Poetry|last=Wu|first=John C. H.|publisher=Charles E. Tuttle|year=1972|isbn=978-0804801973|location=|pages=|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/fourseasonsoftan0000wuji}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Chan|first=Ming K.|title=The Historiography of the Tzu-Chih T'ung-Chien: A Survey|date=1974|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/40726165|journal=Monumenta Sercia|volume=31|pages=1–38|doi=10.1080/02549948.1974.11731093|jstor=40726165|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Cho-ying|first=Li|date=2018|title=A Failed Peripheral Hegemonic State with a Limited Mandate of Heaven: Politico-Historical Reflections of a Survivor of the Southern Tang|url=|journal=Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies|volume=48|issue=2|pages=243–285|doi=10.6503/THJCS.201806_48(2).0002|via=Airiti}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|first=Hugh|last=Clark|date=2017|title=Why Does the Tang-Song Interregnum Matter? Part Two: The Social and Cultural Initiatives of the South|url=|journal=Journal of Song-Yuan Studies|volume=47|pages=1–31|doi=10.1353/sys.2017.0001|s2cid=165226638}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Clark|first=Hugh|date=2016b|title=Why does the Tang-Song Interregnum matter?: A focus on the economies of the south|url=|journal=Journal of Song-Yuan Studies|volume=46|pages=1–28|doi=10.1353/sys.2016.0002|s2cid=165844099}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Davis|first=Richard|date=1983|title=Historiography as Politics in Yang Wei-chen's 'Polemic on Legitimate Succession'|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/4528281|journal=T'oung Pao|volume=69|issue=1/3|pages=33–72|doi=10.1163/156853283X00045|jstor=4528281|via=Brill}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Hartwell|first=David|title=The Imperial Treasuries: Finance and Power in Song China|date=1988|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/23497391|journal=Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies|volume=20|issue=20|pages=18–89|jstor=23497391|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Horesh|first=Niv|title='Cannot be Fed on when Starving': An Analysis of the Economic Thought Surrounding China's Earlier Use of Paper Money|date=2013|url=https://doi.org/10.1017/S1053837213000229|journal=Journal of the History of Economic Thought|volume=35|issue=3|pages=373–395|doi=10.1017/S1053837213000229|s2cid=155064802|via=Cambridge University}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Kurz|first=Johannes|date=2016|title=On the Unification Plans of the Southern Tang Dynasty|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13173/jasiahist.50.1.0023|journal=Journal of Asian History|volume=50|issue=1|pages=23–45|doi=10.13173/jasiahist.50.1.0023|jstor=10.13173/jasiahist.50.1.0023|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Kurz|first=Johannes|date=2016|title=Song Taizong, the 'Record of Jiangnan' ('Jiangnan lu'), and an Alternate Ending to the Tang|url=|journal=Journal of Song-Yuan Studies|volume=46|pages=29–55|doi=10.1353/sys.2016.0003|s2cid=165211485}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Kurz|first=Johannes L.|date=2014|title=On the Southern Tang Imperial Genealogy|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7817/jameroriesoci.134.4.601|journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society|volume=134|issue=4|pages=601–620|doi=10.7817/jameroriesoci.134.4.601|jstor=10.7817/jameroriesoci.134.4.601|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Kurz|first=Johannes|date=2012|title=The Consolidation of Official Historiography during the Early Northern Song Dynasty|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/41933604|journal=Journal of Asian History|volume=46|issue=1|pages=13–35|jstor=41933604|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Kurz|first=Johannes|date=1998|title=The Invention of a "Faction" in Song Historical Writings on the Southern Tang|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/23496061|journal=Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies|volume=28|issue=28|pages=1–35|jstor=23496061|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Kurz|first=Johannes|date=1994|title=Sources for the History of the Southern Tang (937-975)|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/23496127|journal=Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies|volume=24|issue=24|pages=217–235|jstor=23496127|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Lamouroux|first=Christian|date=1995|title=Crise politique et développement rizicole en Chine : la région du Jiang-Huai (VIIIe – Xe siècles)|url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/befeo_0336-1519_1995_num_82_1_2883|journal=Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient|language=FR|volume=82|pages=145–184|doi=10.3406/befeo.1995.2883|via=}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Lee|first=De-nin D.|date=2004|title=Fragments for Constructing a History of Southern Tang Painting|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/23496260|journal=Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest|volume=34|issue=34|pages=1–39|jstor=23496260|via=JSTOR}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Li|first=Man|date=2016|title=Where is 'Yingyou' : the 'Tea Route' between Khitan and Southern Tang and its ports of departure|url=https://www.academia.edu/25290263|journal=National Maritime Research|location=[[Shanghai]]|volume=2|pages=31–46|isbn=978-7-5325-8037-8|via=Academia.edu}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Pak-sheung|first=Ng|date=2016|title=A Regional Cultural Tradition in Song China: "The Four Treasures of the Study of the Southern Tang" ('Nan Tang wenfang sibao')|url=|journal=Journal of Song-Yuan Studies|volume=46|pages=57–117|doi=10.1353/sys.2016.0004|s2cid=165887772}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal|last=Woolley|first=Nathan|date=2014|title=From restoration to unification: legitimacy and loyalty in the writings of Xu Xuan (917–992)|url=|journal=Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies|volume=77|issue=3|pages=547–567|doi=10.1017/S0041977X14000536|via=Cambridge University Press}} |

|||

* {{Cite thesis|last=Kim|first=Hanshin|title=The Transformation in State and Elite Responses to Popular Religious Beliefs|date=2012|degree=PhD|publisher=University of California, Los Angeles|url=https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52v2q1k3|doi=}} |

|||

* {{Cite thesis|last=Krompart|first=Robert J.|title=The Southern Restoration of T'ang: Counsel, Policy, and Parahistory in the Stabilization of the Chiang-Huai Region, 887–943|date=1973|degree=PhD|publisher=University of California, Berkeley|url=https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100790995|doi=}} |

|||

* {{Cite thesis|last=Standen|first=Naomi|title=Frontier crossings from north China to Liao, c.900-1005|date=1994|degree=PhD|publisher=Durham University|url=http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1623/|doi=}} |

|||

* {{Cite thesis|last=Woolley|first=Nathan|title=Religion and Politics in the Writings of Xu Xuan (917-92)|date=2010|degree=PhD|publisher=Australian National University|url=https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/150763|doi=}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://primaltrek.com/blog/2015/06/10/vault-protector-coins/|url-status=live|title=Vault Protector Coins.|date=10 June 2015|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=12 January 2020|author-last=Ashkenazy|author-first=Gary|work=Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture|language=en}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://primaltrek.com/chinesecoins.html|url-status=live|title=Chinese coins – 中國錢幣|date=16 November 2016|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=16 September 2018|author-last=Ashkenazy|author-first=Gary|work=Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture|language=en}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{cite web|url=http://ask.kedo.gov.cn/c/2015-08-21/811081.shtml|url-status=live|title=收藏迷带你深度游钱币博物馆.|date=21 August 2015|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=14 January 2020|website=|author-last=Kao|author-first=Garry|publisher=蝌蚪五线谱|language=zh-cn}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://www.calgarycoin.com/reference/china/china4.htm#south_t'ang|url-status=live|title=Chinese Cast Coins – Southern T'ang Dynasty AD 937–978.|author-last=Kokotailo|author-first=Robert|date=2018|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=16 September 2018|work=Calgary Coin & Antique Gallery – Chinese Cast Coins|language=en}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{нормативна контрола}} |

{{нормативна контрола}} |

||

Верзија на датум 14. јануар 2023. у 08:14

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| АНТИКА | |||||||

| Неолит c. 8500 – c. 2070 п. н. е. | |||||||

| Династија Сја c. 2070 – c. 1600 п. н. е. | |||||||

| Династија Шанг c. 1600 – c. 1046 п. н. е. | |||||||

| Династија Џоу c. 1046 – 256 п. н. е. | |||||||

| Западни Џоу | |||||||

| Источни Џоу | |||||||

| Пролеће и Јесен | |||||||

| Зараћене државе | |||||||

| ЦАРСТВО | |||||||

| Династија Ћин 221–206 п. н. е. | |||||||

| Династија Хан 206 п. н. е. – 220 н. е. | |||||||

| Западни Хан | |||||||

| Династија Син | |||||||

| Источни Хан | |||||||

| Три краљевства 220–280 | |||||||

| Веј, Шу и Ву | |||||||

| Династија Ђин 265–420 | |||||||

| Западни Ђин | |||||||

| Источни Ђин | Шеснаест краљевстава | ||||||

| Јужне и Сјеверне династије 420–589 | |||||||

| Династија Суеј 581–618 | |||||||

| Династија Танг 618–907 | |||||||

| (Друга Џоу династија 690–705) | |||||||

| Пет династија и десет краљевстава 907–960 |

Династија Љао 907–1125 | ||||||

| Династија Сунг 960–1279 |

|||||||

| Северни Сунг | Западни Сја | ||||||

| Јужни Сунг | Ђин | ||||||

| Династија Јуан 1271–1368 | |||||||

| Династија Минг 1368–1644 | |||||||

| Династија Ћинг 1644–1911 | |||||||

| САВРЕМЕНО ДОБА | |||||||

| Република Кина 1912–1949 | |||||||

| Народна Република Кина 1949–садашњост |

Република Кина (Тајван) 1949–садашњост | ||||||

Пет династија и десет краљевстава (Шаблон:Јез-кин-туп) је израз који се користи за турбулентни период кинеске историје који је започео 907. падом династије Танг, а завршио успоставом династије Сунг 960. године, односно формалном обновом политичког јединства царске Кине под њеном влашћу 979. Име је добила по пет династија које су представљале формалне насљеднике династије Танг те се брзо измијениле на пријестољу од 907. до 960. као и по 10 одметнутих држава (чији је број у стварности био већи од 12). Иако је на његовом крају Кина изашла као обновљена политичка цјелина, неки од ранијих територија на сјеверу су потпали под власт тада основане китанске династије Љао.

Пет династија:

- Династија Каснији Лианг (1. јун 907–923)

- Династија Каснији Танг (923–936)

- Латер Јин Дyнастy (936–947)

- Династија Каснији Хан (947–951 или 979, зависно сматра ли се Сјеверни Хан легитимним насљедником династије)

- Династија Каснији Зхоу (951–960)

Десет краљевстава: Ву (907-937), Wuyue (907-978), Мин (909-945), Чу (907-951), Јужни Хан (917-971), Рани Шу (907-925), Касни Шу (934-965), Јингнан (924-963), Јужни Танг (937-975), Сјеверни Хан (951-979).

Остале државе/династије/режими: Yan, Qi, Zhao, Yiwu Jiedushi, Dingnan Jiedushi, Wuping Jiedushi, Qingyuan Jiedushi, Yin, Ganzhou, Shazhou, Liangzhou.

Позадина

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Towards the end of the Tang dynasty, the imperial government granted increased powers to the jiedushi, the regional military governors. The An Lushan (755–763) and Huang Chao rebellions weakened the imperial government, and by the early 10th century the jiedushi commanded de facto independence from its authority. In the last decades of the Tang dynasty, they were not even appointed by the central court any more, but developed hereditary systems, from father to son or from patron to protégé. They had their own armies rivaling the "palace armies" and amassed huge wealth, as testified by their sumptuous tombs.[1] Due to the decline of Tang central authority after the An Lushan Rebellion, there was growing tendency to superimpose large regional administrations over the old districts and prefectures that had been used since the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC). These administrations, known as circuit commissions, would become the boundaries of the later Southern regimes; many circuit commissioners became the emperors or kings of these states.[2]

North

According to Nicholas Tackett, the three provinces of Hebei: Chengde, Youzhou, Weibo, were able to maintain much greater autonomy from the central government in the aftermath of the An Lushan rebellion. With their administration under local military control, these provinces never submitted tax revenues and governorships lapsed into hereditary succession. They engaged in occasional war with the central government, or against each other, and Youzhou seemed to conduct its own foreign policy. This meant that the culture of these northeastern provinces started diverging from the capital. Many of the elites in post-Tang China, including the future emperors of the Song dynasty, came from this region.[3]

The administrations of the Five Dynasties and the early Song dynasty shared a pattern of being disproportionately drawn from the families of military governors in northern and northwestern China (Hebei, Shanxi, Shaanxi), their personal staff, and the bureaucrats who served in the capitals of the Five dynasties. These families had risen to prominence due to the unraveling of central authority after the An Lushan Rebellion, despite lacking esteemed ancestry.[4] The historian Deng Xiaonan argued that many of these military families, including the Song imperial family, were of mixed Han Chinese-Turkic-Kumo Xi ancestry.[5]

The Southern regimes generally had more stable and effective government during this period.[6] The Qing historian Wang Fuzhi (1619–1692) wrote that this period can be compared to the earlier Warring States period of ancient China, remarking that none of the rulers could be described as "Son of Heaven". These rulers, despite claiming the status of emperor, sometimes dealt with each other on terms of diplomatic equality out of pragmatic concern. This concept of "sharing the Mandate of Heaven" as "sibling states" was the result of the brief balance of power. After the reunification of China by the Song dynasty, the Song embarked on a special effort to denounce such arrangements.[7][8]

South

Even the rulers of the Southern states were almost all military leaders from the north with their key officers and elite forces also hailing from the north, since the bulk of the Tang army was based in the north.[9] The founders of Wu and Former Shu were 'rogues' from Huainan and Xuchang respectively, the founder of Min was a minor government staffer from Huainan, the founder of Wuyue was a 'rogue' from Hangzhou, the founder of Chu was (according to one source) a carpenter from Xuchang, the founder of Jingnan was a slave from Shanzhou and the founder of Southern Han was a southern tribal chief.[10] The Southern kingdoms were founded by men of low social status who rose up through superior military ability, who were later scorned as "bandits" by future scholars. However, once established, these rulers took great pains to portray themselves as promoters of culture and economic development so as to legitimise their rule; many wooed former Tang courtiers to help administer their states.[11]

The economies of each of the southern regions had prospered in the late Tang. Guangdong and Fujian were the sites of important port cities trading exotic goods, the middle Yangtze and Sichuan were centres of tea and porcelain production, and the Yangtze delta was a center of extremely high agricultural production and an entrepot for the other regions. The regions were economically interdependent. Sui and Tang policies, while paying little attention to developing the south, gave the south room to innovate free of tight administrative controls. The dominant northern officials had been unwilling to serve in the south during the Tang, and so southerners were recruited by the Tang to serve in a local capacity under the "Southern Selection" supplemental system. These southern officials became the administrative core of the Ten Kingdoms and later dominated the bureaucracy by the mid-Song.[12]

Извори

- ^ Xiu Ouyang (2004). Historical Records of the Five Dynasties. Превод: Richard L. Davis. Columbia University Press. стр. lv—lxv. ISBN 9780231128278. The information was taken from Richard L. Davis's introduction.

- ^ Robert M. Hartwell (1982). „Demographic, Political, and Social Transformations of China, 750–1550”. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 42 (2): 397.

- ^ Nicolas Tackett (2014). The Destruction of the Medieval Chinese Aristocracy. Harvard University Press. стр. 151—184. ISBN 9780674492059.

- ^ Robert M. Hartwell (1982). „Demographic, Political, and Social Transformations of China, 750–1550”. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 42 (2): 405—408.

- ^ Nicolas Tackett (2017). The Origins of the Chinese Nation. University of California, Berkeley: Cambridge University Press. стр. 100. ISBN 978-1-316-64748-6.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram, A History of China (1977), "Chapter IX: The Epoch of the Second Division of China."

- ^ Nicolas Tackett (2017). The Origins of the Chinese Nation. University of California, Berkeley: Cambridge University Press. стр. 72—73. ISBN 978-1-316-64748-6.

- ^ Wang, Hongjie (2011). Power and politics in tenth-century China : the Former Shu regime. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press. стр. 2, 5—6, 8, 11—12, 115, 118, 122, 233, 247, 248. ISBN 978-1-60497-764-6.

- ^ Wang, Hongjie (2011). Power and politics in tenth-century China : the Former Shu regime. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press. стр. 82. ISBN 978-1-60497-764-6.

- ^ Peter Lorge (2011). Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. стр. 51—78.

- ^ Benjamin Brose (2015). Patrons and Patriarchs: Regional Rulers and Chan Monks during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. University of Hawaii Press. стр. 20—21. ISBN 978-0824857240.

- ^ Hugh Clark (2021). China during the Tang-Song Interregnum, 878–978: New Approaches to the Southern Kingdoms. Routledge. стр. 101—103. ISBN 9781000426397.

Литература

- Michael Szonyi (2017). A Companion to Chinese History. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 9781118624548.

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2011). China's Southern Tang Dynasty (937-976). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45496-4.

- Davis, Richard L. (2015). From Warhorses to Ploughshares: The Later Tang Reign of Emperor Mingzong. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789888208104.

- Dudbridge, Glen (2013). A Portrait of Five Dynasties China: From the Memoirs of Wang Renyu (880-956). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199670680.

- Hung, Hing Ming (2014). Ten States, Five Dynasties, One Great Emperor: How Emperor Taizu Unified China in the Song Dynasty. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62894-072-5.

- Lorge, Peter, ур. (2011). Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. The Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-9629964184.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1954). Empire of Min: A South China Kingdom of the Tenth Century. Tuttle Publishing.

- Wang Gungwu (1963). The Structure of Power in North China During the Five Dynasties. Stanford University Press.

- Wang Hongjie (2011). Power and Politics in Tenth-Century China: The Former Shu Regime. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1604977646.

- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01212-7.

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2010). „The Notion of Tribe in Medieval China: Ouyang Xiu and the Shatup Dynastic Myth”. Miscellanea Asiatica: 610—613.

- Barenghi, Maddalena (2014). Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923–936) and Later Jin (936–947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh century Sources (PhD). стр. 3-4.

- Ouyang, Xiu (5. 4. 2004). Historical Records of the Five Dynasties. Превод: Richard L. Davis. Columbia University Press. стр. 76—. ISBN 978-0-231-50228-3.

- Ong, Chang Woei (2008). Men of Letters Within the Passes: Guanzhong Literati in Chinese History, 907–1911. Harvard University Asia Center. стр. 29. ISBN 978-0-674-03170-8.

- Chen, Yuan Julian (2014). „"Legitimation Discourse and the Theory of the Five Elements in Imperial China." Journal of Song-Yuan Studies 44 (2014): 325–364.”. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies (на језику: енглески). 44 (1): 325. S2CID 147099574. doi:10.1353/sys.2014.0000.

- Tao Gu 陶穀 (n.d.e). Qīngyì lù (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Guang, Sima (1084). Zīzhì Tōngjiàn (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Ji, Yun (1798). Sìkù Quánshū Zǒngmù Tíyào (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Li, Tao (1193). Xù Zīzhì Tōngjiàn Chángbiān (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Lu, You 陸游 (1184). Lù Shì Nán Táng Shū (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Ling, Ma 馬令 (n.d.e). Mǎ Shì Nán Táng Shū (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Ouyang, Xiu (1073). Wǔdài Shǐjì (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Ouyang, Xiu (n.d.e). Ōuyáng xiū jí (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Renchen, Wu (n.d.e). Shíguó chūnqiūn (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Toqto'a (1343). Sòng Shǐ (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Wenying (1078). Yù Hú Qīng Huà (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Xue, Juzheng (974). Jiù Wǔdài Shǐ (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Zheng, Wenbao 鄭文寶 (978). Nán Táng Jìn Shì (на језику: кинески) — преко Викизворника.

- Brose, Benjamin (2015). Patrons and Patriarchs : Regional Rulers and Chan monks during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Studies in East Asian Buddhism. 25. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5381-5.

- Clark, Hugh R. (2016). The Sinitic Encounter in Southeast China through the First Millennium CE. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5160-6.

- Clark, Hugh R. (2009). „The Southern Kingdoms between the T’ang and the Sung, 907–979”. Ур.: Twitchett, Denis; Smith, Paul J. The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1. The Cambridge History of China. 5. New York: Cambridge University Press. стр. 133—205. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1.

- Fu, Chonglan; Cao, Wenming (2019). Introduction to the Urban History of China. China Connections. Превод: Zhang, Qinggang. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-981-13-8206-2. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8207-9.

- Hartill, David (2005). Cast Chinese coins. Trafford: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1412054669.

- Hay, Jonathan (2012). „Tenth-Century Painting before Song Taizong’s Reign: A Macrohistorical View”. Ур.: Hung, Wu. Tenth-century China and Beyond: Art and Visual Culture in a Multi-centered Age. Chicago: The Center for the Art of East Asia, University of Chicago. стр. 285—318. ISBN 978-1588861153.

- Kurz, Johannes (2011b). „Han Xizai (902–970): An Eccentric Life in Exciting Times”. Ур.: Lorge, Peter. Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Hong Kong: China University Press. стр. 79—98. ISBN 978-9629964184.

- Kurz, Johannes (1997). „The Yangzi in the Negotiations between the Southern Tang and Its Northern Neighbors (Mid-Tenth Century)”. Ур.: Dabringhaus, Sabine; Ptak, Roderich; Teschke, Richard. China and Her Neighbours: Borders, Visions of the Other, Foreign Policy 10th to 19th Century. South China and maritime Asia. 6. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3447039426.

- Lorge, Peter (2013). „Fighting Against Empire: Resistance to the Later Zhou and Song Conquest of China”. Ур.: Lorge, Peter A. Debating War in Chinese History. Leiden and New York: Brill. стр. 107—140. ISBN 978-90-04-22372-1.

- Lorge, Peter A. (2005). War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31690-1.

- Mote, F. W. (1999). Imperial China (900-1800). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674012127.

- Standen, Naomi (2009). „The Five Dynasties”. Ур.: Twitchett, Denis; Smith, Paul J. The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1. The Cambridge History of China. 5. New York: Cambridge University Press. стр. 38—132. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1.

- Twitchett, Denis; Tietze, Klaus-Peter (1994). „The Liao”. Ур.: Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis. Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368. The Cambridge History of China. 6. New York: Cambridge University Press. стр. 43—153. ISBN 0-521-24331-9.

- Worthy, Edmund H. (1983). „Diplomacy for Survival: Domestic and Foreign Relations of Wu Yüeh, 907-978”. Ур.: Rossabi, Morris. China among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries. Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. стр. 17—46. ISBN 0520043839.

- Wu, John C. H. (1972). The Four Seasons of Tang Poetry

. Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 978-0804801973.

. Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 978-0804801973. - Chan, Ming K. (1974). „The Historiography of the Tzu-Chih T'ung-Chien: A Survey”. Monumenta Sercia. 31: 1—38. JSTOR 40726165. doi:10.1080/02549948.1974.11731093 — преко JSTOR.

- Cho-ying, Li (2018). „A Failed Peripheral Hegemonic State with a Limited Mandate of Heaven: Politico-Historical Reflections of a Survivor of the Southern Tang”. Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies. 48 (2): 243—285. doi:10.6503/THJCS.201806_48(2).0002 — преко Airiti.

- Clark, Hugh (2017). „Why Does the Tang-Song Interregnum Matter? Part Two: The Social and Cultural Initiatives of the South”. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 47: 1—31. S2CID 165226638. doi:10.1353/sys.2017.0001.

- Clark, Hugh (2016b). „Why does the Tang-Song Interregnum matter?: A focus on the economies of the south”. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 46: 1—28. S2CID 165844099. doi:10.1353/sys.2016.0002.

- Davis, Richard (1983). „Historiography as Politics in Yang Wei-chen's 'Polemic on Legitimate Succession'”. T'oung Pao. 69 (1/3): 33—72. JSTOR 4528281. doi:10.1163/156853283X00045 — преко Brill.

- Hartwell, David (1988). „The Imperial Treasuries: Finance and Power in Song China”. Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies. 20 (20): 18—89. JSTOR 23497391 — преко JSTOR.

- Horesh, Niv (2013). „'Cannot be Fed on when Starving': An Analysis of the Economic Thought Surrounding China's Earlier Use of Paper Money”. Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 35 (3): 373—395. S2CID 155064802. doi:10.1017/S1053837213000229 — преко Cambridge University.

- Kurz, Johannes (2016). „On the Unification Plans of the Southern Tang Dynasty”. Journal of Asian History. 50 (1): 23—45. JSTOR 10.13173/jasiahist.50.1.0023. doi:10.13173/jasiahist.50.1.0023 — преко JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (2016). „Song Taizong, the 'Record of Jiangnan' ('Jiangnan lu'), and an Alternate Ending to the Tang”. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 46: 29—55. S2CID 165211485. doi:10.1353/sys.2016.0003.

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2014). „On the Southern Tang Imperial Genealogy”. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 134 (4): 601—620. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.134.4.601. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.134.4.601 — преко JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (2012). „The Consolidation of Official Historiography during the Early Northern Song Dynasty”. Journal of Asian History. 46 (1): 13—35. JSTOR 41933604 — преко JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (1998). „The Invention of a "Faction" in Song Historical Writings on the Southern Tang”. Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies. 28 (28): 1—35. JSTOR 23496061 — преко JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (1994). „Sources for the History of the Southern Tang (937-975)”. Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies. 24 (24): 217—235. JSTOR 23496127 — преко JSTOR.

- Lamouroux, Christian (1995). „Crise politique et développement rizicole en Chine : la région du Jiang-Huai (VIIIe – Xe siècles)”. Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (на језику: француски). 82: 145—184. doi:10.3406/befeo.1995.2883.

- Lee, De-nin D. (2004). „Fragments for Constructing a History of Southern Tang Painting”. Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest. 34 (34): 1—39. JSTOR 23496260 — преко JSTOR.

- Li, Man (2016). „Where is 'Yingyou' : the 'Tea Route' between Khitan and Southern Tang and its ports of departure”. National Maritime Research. Shanghai. 2: 31—46. ISBN 978-7-5325-8037-8 — преко Academia.edu.

- Pak-sheung, Ng (2016). „A Regional Cultural Tradition in Song China: "The Four Treasures of the Study of the Southern Tang" ('Nan Tang wenfang sibao')”. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 46: 57—117. S2CID 165887772. doi:10.1353/sys.2016.0004.

- Woolley, Nathan (2014). „From restoration to unification: legitimacy and loyalty in the writings of Xu Xuan (917–992)”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 77 (3): 547—567. doi:10.1017/S0041977X14000536 — преко Cambridge University Press.

- Kim, Hanshin (2012). The Transformation in State and Elite Responses to Popular Religious Beliefs (Теза). University of California, Los Angeles.

- Krompart, Robert J. (1973). The Southern Restoration of T'ang: Counsel, Policy, and Parahistory in the Stabilization of the Chiang-Huai Region, 887–943 (Теза). University of California, Berkeley.

- Standen, Naomi (1994). Frontier crossings from north China to Liao, c.900-1005 (Теза). Durham University.

- Woolley, Nathan (2010). Religion and Politics in the Writings of Xu Xuan (917-92) (Теза). Australian National University.

- Ashkenazy, Gary (10. 6. 2015). „Vault Protector Coins.”. Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture (на језику: енглески). Приступљено 12. 1. 2020.

- Ashkenazy, Gary (16. 11. 2016). „Chinese coins – 中國錢幣”. Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture (на језику: енглески). Приступљено 16. 9. 2018.

Спољашње везе

- Kao, Garry (21. 8. 2015). „收藏迷带你深度游钱币博物馆.” (на језику: кинески). 蝌蚪五线谱. Приступљено 14. 1. 2020.

- Kokotailo, Robert (2018). „Chinese Cast Coins – Southern T'ang Dynasty AD 937–978.”. Calgary Coin & Antique Gallery – Chinese Cast Coins (на језику: енглески). Приступљено 16. 9. 2018.