Јаје — разлика између измена

. |

|||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{short description|Органска посуда у којој први ембрион почиње да се развија}} |

|||

{{друга употреба|Јаје (храна)}} |

{{друга употреба|Јаје (храна)}} |

||

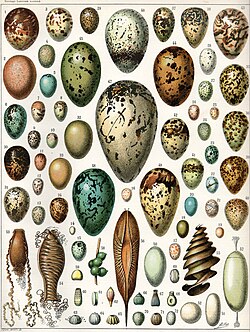

[[Датотека:Oeufs002b.jpg|250px|Јаја разних [[птица]], [[turtle|рептила]], разних [[cartilaginous fish|хрскавичних риба]], [[cephalopod|сипа]] и разних [[butterflies and moths|лептира и мољаца]].|right|thumb]] |

|||

[[Датотека:Anatomy_of_an_egg.svg|мини|десно| |

[[Датотека:Anatomy_of_an_egg.svg|мини|десно|250п|'''Схема грађе птичјег јајета:'''<br /> |

||

1. љуска јајета<br /> |

1. љуска јајета<br /> |

||

2. спољашња мембрана<br /> |

2. спољашња мембрана<br /> |

||

| Ред 18: | Ред 20: | ||

]] |

]] |

||

'''Јаје''' представља [[јајна ћелија|јајну ћелију]] [[животиње|животиња]], окружену јајним опнама.<ref name="Khanna2005">{{cite book|author=D.R. Khanna|title=Biology of Birds|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fDblIChi7KwC&pg=PA130|date=1. 1. 2005|publisher=Discovery Publishing House|isbn=978-81-7141-933-3|url-status=live|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160510084347/https://books.google.com/books?id=fDblIChi7KwC&pg=PA130|archivedate=10. 5. 2016.|pages=130}}</ref> Код свих животиња изузев неких [[дупљари|дупљара]], јајне ћелије се „пакују“ у јајне опне пре или након [[оплођење|оплођења]]. Јаје је репродуктивна ћелија женке и након [[Оплодња|оплодње]] са мушком полном ћелијом ([[Сперматозоид|сперматозоидом]]), ако се исправно инкубира, развиће се пиле. Током двадесетодневног периода док је [[ембрион]] у љусци, садржај у јајету служи као једини извор хране за пиле у развоју. |

'''Јаје''' представља [[јајна ћелија|јајну ћелију]] [[животиње|животиња]], окружену јајним опнама.<ref name="Khanna2005">{{cite book|author=D.R. Khanna|title=Biology of Birds|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fDblIChi7KwC&pg=PA130|date=1. 1. 2005|publisher=Discovery Publishing House|isbn=978-81-7141-933-3|url-status=live|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160510084347/https://books.google.com/books?id=fDblIChi7KwC&pg=PA130|archivedate=10. 5. 2016.|pages=130}}</ref> Код свих животиња изузев неких [[дупљари|дупљара]], јајне ћелије се „пакују“ у јајне опне пре или након [[оплођење|оплођења]]. Јаје је репродуктивна ћелија женке и након [[Оплодња|оплодње]] са мушком полном ћелијом ([[Сперматозоид|сперматозоидом]]), ако се исправно инкубира, развиће се пиле. Током двадесетодневног периода док је [[ембрион]] у љусци, садржај у јајету служи као једини извор хране за пиле у развоју. Јаје је једна од најкомплетнијих намирница познатих човеку јер садржи изванредно избалансиран однос [[Протеин|протеина]], [[масти]], [[Угљени хидрат|угљених хидрата]], минерала и [[Vitamin|витамина]]. |

||

Јаје је једна од најкомплетнијих намирница познатих човеку јер садржи изванредно избалансиран однос [[Протеин|протеина]], [[масти]], [[Угљени хидрат|угљених хидрата]], минерала и [[Vitamin|витамина]]. |

|||

== Љуска јајета == |

== Љуска јајета == |

||

'''Јаје''' је обавијено љуском која је састављена од кречњака. она је веома слаба јер је кречњачки слој веома танак. |

'''Јаје''' је обавијено љуском која је састављена од кречњака. она је веома слаба јер је кречњачки слој веома танак. |

||

== Научне класификације == |

|||

{{рут}} |

|||

Scientists often classify animal reproduction according to the degree of development that occurs before the new individuals are expelled from the adult body, and by the yolk which the egg provides to nourish the embryo. |

|||

===Egg size and yolk=== |

|||

[[Vertebrate]] eggs can be classified by the relative amount of [[yolk]]. Simple eggs with little yolk are called ''microlecithal'', medium-sized eggs with some yolk are called ''mesolecithal'', and large eggs with a large concentrated yolk are called ''macrolecithal''.<ref name="Romer & Parson">[[Alfred Romer|Romer, A. S.]] & Parsons, T. S. (1985): ''The Vertebrate Body.'' (6th ed.) Saunders, Philadelphia.</ref> This classification of eggs is based on the eggs of [[chordata|chordates]], though the basic principle extends to the whole [[animalia|animal kingdom]]. |

|||

==== Microlecithal ==== |

|||

[[File:Toxocara embryonated eggs.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Microlecithal eggs from the [[Nematoda|roundworm]] ''[[Toxocara]]'']] |

|||

[[File:Paragonimus westermani 01.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Microlecithal eggs from the [[flatworm]] ''[[Paragonimus westermani]]'']] |

|||

Small eggs with little yolk are called microlecithal. The yolk is evenly distributed, so the cleavage of the egg cell cuts through and divides the egg into cells of fairly similar sizes. In [[sponges]] and [[cnidaria]]ns the dividing eggs develop directly into a simple larva, rather like a [[morula]] with [[cilium|cilia]]. In cnidarians, this stage is called the [[planula]], and either develops directly into the adult animals or forms new adult individuals through a process of [[budding]].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Reitzel|first=A.M.|author2=Sullivan, J.C|author3=Finnery, J.R|title=Qualitative shift to indirect development in the parasitic sea anemone ''Edwardsiella lineata''|journal=Integrative and Comparative Biology|year=2006|volume=46|issue=6|pages=827–837|doi=10.1093/icb/icl032|pmid=21672788|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Microlecithal eggs require minimal yolk mass. Such eggs are found in [[flatworm]]s, [[roundworm]]s, [[annelid]]s, [[bivalve]]s, [[Echinodermata|echinoderms]], the [[lancelet]] and in most marine [[arthropod]]s.<ref name="Barns">Barns, R.D. (1968): Invertebrate Zoology. W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia. 743 pages</ref> In anatomically simple animals, such as cnidarians and flatworms, the fetal development can be quite short, and even microlecithal eggs can undergo direct development. These small eggs can be produced in large numbers. In animals with high egg mortality, microlecithal eggs are the norm, as in bivalves and marine arthropods. However, the latter are more complex anatomically than e.g. flatworms, and the small microlecithal eggs do not allow full development. Instead, the eggs hatch into [[larva]]e, which may be markedly different from the adult animal. |

|||

In placental mammals, where the embryo is nourished by the mother throughout the whole fetal period, the egg is reduced in size to essentially a naked egg cell. |

|||

====Mesolecithal==== |

|||

[[File:Frogspawn closeup.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Frog]]spawn is mesolecithal.]] |

|||

Mesolecithal eggs have comparatively more yolk than the microlecithal eggs. The yolk is concentrated in one part of the egg (the ''vegetal pole''), with the [[cell nucleus]] and most of the [[cytoplasm]] in the other (the ''animal pole''). The cell cleavage is uneven, and mainly concentrated in the cytoplasma-rich animal pole.<ref name=Hildebrand>Hildebrand, M. & Gonslow, G. (2001): Analysis of Vertebrate Structure. 5th edition. ''John Wiley & Sons, Inc''. [[New York City]]</ref> |

|||

The larger yolk content of the mesolecithal eggs allows for a longer fetal development. Comparatively anatomically simple animals will be able to go through the full development and leave the egg in a form reminiscent of the adult animal. This is the situation found in [[hagfish]] and some [[snail]]s.<ref name=Gorbman>{{cite journal|last=Gorbman|first=A.|title=Hagfish development|journal= Zoological Science|date=June 1997|volume=14|issue=3|pages=375–390|doi=10.2108/zsj.14.375|s2cid=198158310}}</ref><ref name="Barns"/> Animals with smaller size eggs or more advanced anatomy will still have a distinct larval stage, though the larva will be basically similar to the adult animal, as in [[lamprey]]s, [[coelacanth]] and the [[salamander]]s.<ref name=Hildebrand/> |

|||

====Macrolecithal==== |

|||

[[File:Tortoise-Hatchling.jpg|thumb|right|250px|A baby [[tortoise]] begins to emerge "fully developed" from its macrolecithal egg.]] |

|||

Eggs with a large yolk are called macrolecithal. The eggs are usually few in number, and the embryos have enough food to go through full fetal development in most groups.<ref name="Romer & Parson"/> Macrolecithal eggs are only found in selected representatives of two groups: [[Cephalopod]]s and [[vertebrate]]s.<ref name="Romer & Parson"/><ref>Nixon, M. & Messenger, J.B (eds) (1977): The Biology of Cephalopods. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London, pp 38–615</ref> |

|||

Macrolecithal eggs go through a different type of development than other eggs. Due to the large size of the yolk, the cell division can not split up the yolk mass. The fetus instead develops as a plate-like structure on top of the yolk mass, and only envelopes it at a later stage.<ref name="Romer & Parson"/> A portion of the yolk mass is still present as an external or semi-external [[yolk sac]] at hatching in many groups. This form of fetal development is common in [[bony fish]], even though their eggs can be quite small. Despite their macrolecithal structure, the small size of the eggs does not allow for direct development, and the eggs hatch to a larval stage ("fry"). In terrestrial animals with macrolecithal eggs, the large volume to surface ratio necessitates structures to aid in transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide, and for storage of waste products so that the embryo does not suffocate or get poisoned from its own waste while inside the egg, see [[amniote]].<ref name="Stewart J. R. 1997">Stewart J. R. (1997): ''Morphology and evolution of the egg of oviparous amniotes''. In: S. Sumida and K. Martin (ed.) Amniote Origins-Completing the Transition to Land (1): 291–326. London: Academic Press.</ref> |

|||

In addition to bony fish and cephalopods, macrolecithal eggs are found in [[Chondrichthyes|cartilaginous fish]], [[reptile]]s, [[bird]]s and [[monotreme]] mammals.<ref name=Hildebrand/> The eggs of the [[coelacanth]]s can reach a size of {{cvt|9|cm}} in diameter, and the young go through full development while in the [[uterus]], living on the copious yolk.<ref>Fricke, H.W. & Frahm, J. (1992): Evidence for lecithotrophic viviparity in the living coelacanth. ''Naturwissenschaften'' no 79: pp. 476–479</ref> |

|||

===Egg-laying reproduction=== |

|||

Animals are commonly classified by their manner of reproduction, at the most general level distinguishing egg-laying (Latin. ''oviparous'') from live-bearing (Latin. ''viviparous''). |

|||

These classifications are divided into more detail according to the development that occurs before the offspring are expelled from the adult's body. Traditionally:<ref>[[Thierry Lodé]] 2001. Les stratégies de reproduction des animaux (reproduction strategies in animal kingdom). Eds Dunod Sciences, Paris</ref> |

|||

*'''Ovuliparity''' means the female [[Spawn (biology)|spawns]] unfertilized eggs (ova), which must then be externally fertilised. Ovuliparity is typical of [[bony fish]], [[anuran]]s, echinoderms, bivalves and cnidarians. Most aquatic organisms are ovuliparous. The term is derived from the diminutive meaning "little egg". |

|||

*'''Oviparity''' is where fertilisation occurs internally and so the eggs laid by the female are zygotes (or newly developing embryos), often with important outer tissues added (for example, in a chicken egg, no part outside of the yolk originates with the zygote). Oviparity is typical of birds, reptiles, some cartilaginous fish and most arthropods. Terrestrial organisms are typically oviparous, with egg-casings that resist evaporation of moisture. |

|||

*'''Ovo-viviparity''' is where the zygote is retained in the adult's body but there are no ''trophic'' (feeding) interactions. That is, the embryo still obtains all of its nutrients from inside the egg. Most live-bearing fish, amphibians or reptiles are actually ovoviviparous. Examples include the reptile ''[[Anguis fragilis]]'', the sea horse (where zygotes are retained in the male's ventral "marsupium"), and the frogs ''Rhinoderma darwinii'' (where the eggs develop in the vocal sac) and ''Rheobatrachus'' (where the eggs develop in the stomach). |

|||

*'''Histotrophic viviparity''' means embryos develop in the female's [[oviduct]]s but obtain nutrients by consuming other ova, zygotes or sibling embryos ([[oophagy]] or [[adelphophagy]]). This [[intra-uterine cannibalism]] occurs in some sharks and in the black salamander ''Salamandra atra''. [[Marsupials]] excrete a "uterine milk" supplementing the nourishment from the yolk sac.<ref>{{cite book|last1=USA|first1=David O. Norris |location= University of Colorado at Boulder, Colorado, USA |author2= James A. Carr |title=Vertebrate endocrinology.|date=2013|isbn=978-0123948151|page=349|edition=Fifth|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F_NaW1ZcSSAC&q=uterine+milk+marsupial&pg=PA349|access-date=25 November 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171101190341/https://books.google.com/books?id=F_NaW1ZcSSAC&pg=PA349&lpg=PA349&dq=uterine+milk+marsupial&source=bl&ots=M_k_K_2IfP&sig=hRHbDN3R6DMto9XgoDyZWtK2pFQ&hl=no&sa=X&ei=-2x0VPWUKuH-ywOCr4K4Bg&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=uterine%20milk%20marsupial&f=false|archive-date=1 November 2017}}</ref> |

|||

*'''Hemotrophic viviparity''' is where nutrients are provided from the female's blood through a designated organ. This most commonly occurs through a [[placenta]], found in [[placentalia|most mammals]]. Similar structures are found in some sharks and in the lizard ''Pseudomoia pagenstecheri''.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hamlett|first1=William C.|title=Evolution and morphogenesis of the placenta in sharks|journal=Journal of Experimental Zoology|date=1989|volume=252|issue=S2|pages=35–52|doi=10.1002/jez.1402520406}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Jerez|first1=Adriana|last2=Ramírez-Pinilla|first2=Martha Patricia|title=Morphogenesis of extraembryonic membranes and placentation inMabuya mabouya (Squamata, Scincidae)|journal=Journal of Morphology|date=November 2003|volume=258|issue=2|pages=158–178|doi=10.1002/jmor.10138|pmid=14518010|s2cid=782433}}</ref> In some [[Hylidae|hylid frogs]], the embryo is fed by the mother through specialized [[gill]]s.<ref>{{cite book| editor= Gorbman Peter |editor2= K.T. Pang |editor3= Martin P. Schreibman |others= Aubrey|title=Vertebrate endocrinology : fundamentals and biomedical implications|date=1986|publisher=Academic Press|location=Orlando|isbn=978-0125449014|page=237|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Uuxo-6MkNJ8C&q=Gastrotheca+ovifera+embryo+gill&pg=PA237|access-date=25 November 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171101190341/https://books.google.com/books?id=Uuxo-6MkNJ8C&pg=PA237&lpg=PA237&dq=Gastrotheca+ovifera+embryo+gill&source=bl&ots=YSqFxEyVAI&sig=d1ma005QCJi2T7-sHL0aZPCo3jM&hl=no&sa=X&ei=e3B0VOmGJ4afygPqo4LwDA&ved=0CFgQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=Gastrotheca%20ovifera%20embryo%20gill&f=false|archive-date=1 November 2017}}</ref> |

|||

The term hemotropic derives from the Latin for blood-feeding, contrasted with histotrophic for tissue-feeding.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=histo-%2C+hemo- |title=Online Etymology Dictionary |publisher=Etymonline.com |access-date=2013-07-27 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140514110803/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=histo-%2C+hemo- |archive-date=2014-05-14 }}</ref> |

|||

== Референце == |

== Референце == |

||

{{reflist|30em}} |

{{reflist|30em}} |

||

== Литература == |

|||

{{refbegin|}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70101-5 |pmid=9821418 |title=Safe administration of influenza vaccine to patients with egg allergy |journal=The Journal of Pediatrics |volume=133 |issue=5 |pages=624–8 |year=1998 |last1=James |first1=John M. |last2=Zeiger |first2=Robert S. |last3=Lester |first3=Mitchell R. |last4=Fasano |first4=Mary Beth |last5=Gern |first5=James E. |last6=Mansfield |first6=Lyndon E. |last7=Schwartz |first7=Howard J. |last8=Sampson |first8=Hugh A. |last9=Windom |first9=Hugh H. |last10=Machtinger |first10=Steven B. |last11=Lensing |first11=Shelly }} |

|||

* {{citation |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fLmAYGxmTfIC&q=egg+white+Ovalbumin+Ovotransferrin+Ovomucoid&pg=PA19 |title=Hen eggs |author=Takehiko Yamamoto |author2= Mujo Kim|isbn=9780849340055 |date=1996-12-13 }} |

|||

* Gilbertus. ''Compendium Medicine Gilberti Anglici Tam Morborum Universalium Quam Particularium Nondum Medicis Sed & Cyrurgicis Utilissimum''. Lugduni: Impressum per Jacobum Sacconum, expensis Vincentii de Portonariis, 1510. |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

{{Commonscat|Eggs|Јаје}} |

{{Commonscat|Eggs|Јаје}} |

||

* [[Elmhurst College]], [https://web.archive.org/web/20060525230910/http://www.elmhurst.edu/~chm/vchembook/568denaturation.html Denaturation Protein] |

|||

* [[Exploratorium]], [http://www.exploratorium.edu/cooking/eggs/eggcomposition.html Anatomy of an Egg] |

|||

{{клица-биол}} |

|||

* {{cite web |title=Whale Shark – Cartilaginous Fish |url=http://seaworld.org/en/animal-info/animal-bytes/cartilaginous-fish/whale-shark/ |publisher=[[SeaWorld]] Parks & Entertainment |access-date=2014-06-26 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140609153809/http://seaworld.org/en/animal-info/animal-bytes/cartilaginous-fish/whale-shark/ |archive-date=2014-06-09 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1038/308667a0 |title=Why whip egg whites in copper bowls? |journal=Nature |volume=308 |issue=5960 |pages=667–8 |year=1984 |last1=McGee |first1=Harold J. |last2=Long |first2=Sharon R. |last3=Briggs |first3=Winslow R. |bibcode=1984Natur.308..667M |s2cid=4372579 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |author=Arnaldo Cantani |title=Pediatric Allergy, Asthma and Immunology |url=https://archive.org/details/fundamentalspowd00pech_440 |url-access=limited |publisher=Springer |location=Berlin |year=2008 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/fundamentalspowd00pech_440/page/n728 710]–713 |isbn=978-3-540-20768-9 }} |

|||

* {{Citation|last=Dasgupta|first=Amitava|title=Chapter 2 - Biotin: Pharmacology, Pathophysiology, and Assessment of Biotin Status|date=2019-01-01|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128164297000022|work=Biotin and Other Interferences in Immunoassays|pages=17–35|editor-last=Dasgupta|editor-first=Amitava|publisher=Elsevier|language=en|isbn=978-0-12-816429-7|access-date=2020-08-27}} |

|||

{{нормативна контрола}} |

{{нормативна контрола}} |

||

Верзија на датум 11. мај 2022. у 04:26

1. љуска јајета

2. спољашња мембрана

3. унутрашња мембрана

4. халаза

5. спољашњи албумен (беланце)

6. средишњи албумен (беланце)

7. вителинска мембрана

8. # бластодерм

10. жуто жуманце

11. бело жуманце

12. унутрашњи албумен (беланце)

13. халаза

14. ваздушна комора

15. кутикула

Јаје представља јајну ћелију животиња, окружену јајним опнама.[1] Код свих животиња изузев неких дупљара, јајне ћелије се „пакују“ у јајне опне пре или након оплођења. Јаје је репродуктивна ћелија женке и након оплодње са мушком полном ћелијом (сперматозоидом), ако се исправно инкубира, развиће се пиле. Током двадесетодневног периода док је ембрион у љусци, садржај у јајету служи као једини извор хране за пиле у развоју. Јаје је једна од најкомплетнијих намирница познатих човеку јер садржи изванредно избалансиран однос протеина, масти, угљених хидрата, минерала и витамина.

Љуска јајета

Јаје је обавијено љуском која је састављена од кречњака. она је веома слаба јер је кречњачки слој веома танак.

Научне класификације

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Scientists often classify animal reproduction according to the degree of development that occurs before the new individuals are expelled from the adult body, and by the yolk which the egg provides to nourish the embryo.

Egg size and yolk

Vertebrate eggs can be classified by the relative amount of yolk. Simple eggs with little yolk are called microlecithal, medium-sized eggs with some yolk are called mesolecithal, and large eggs with a large concentrated yolk are called macrolecithal.[2] This classification of eggs is based on the eggs of chordates, though the basic principle extends to the whole animal kingdom.

Microlecithal

Small eggs with little yolk are called microlecithal. The yolk is evenly distributed, so the cleavage of the egg cell cuts through and divides the egg into cells of fairly similar sizes. In sponges and cnidarians the dividing eggs develop directly into a simple larva, rather like a morula with cilia. In cnidarians, this stage is called the planula, and either develops directly into the adult animals or forms new adult individuals through a process of budding.[3]

Microlecithal eggs require minimal yolk mass. Such eggs are found in flatworms, roundworms, annelids, bivalves, echinoderms, the lancelet and in most marine arthropods.[4] In anatomically simple animals, such as cnidarians and flatworms, the fetal development can be quite short, and even microlecithal eggs can undergo direct development. These small eggs can be produced in large numbers. In animals with high egg mortality, microlecithal eggs are the norm, as in bivalves and marine arthropods. However, the latter are more complex anatomically than e.g. flatworms, and the small microlecithal eggs do not allow full development. Instead, the eggs hatch into larvae, which may be markedly different from the adult animal.

In placental mammals, where the embryo is nourished by the mother throughout the whole fetal period, the egg is reduced in size to essentially a naked egg cell.

Mesolecithal

Mesolecithal eggs have comparatively more yolk than the microlecithal eggs. The yolk is concentrated in one part of the egg (the vegetal pole), with the cell nucleus and most of the cytoplasm in the other (the animal pole). The cell cleavage is uneven, and mainly concentrated in the cytoplasma-rich animal pole.[5]

The larger yolk content of the mesolecithal eggs allows for a longer fetal development. Comparatively anatomically simple animals will be able to go through the full development and leave the egg in a form reminiscent of the adult animal. This is the situation found in hagfish and some snails.[6][4] Animals with smaller size eggs or more advanced anatomy will still have a distinct larval stage, though the larva will be basically similar to the adult animal, as in lampreys, coelacanth and the salamanders.[5]

Macrolecithal

Eggs with a large yolk are called macrolecithal. The eggs are usually few in number, and the embryos have enough food to go through full fetal development in most groups.[2] Macrolecithal eggs are only found in selected representatives of two groups: Cephalopods and vertebrates.[2][7]

Macrolecithal eggs go through a different type of development than other eggs. Due to the large size of the yolk, the cell division can not split up the yolk mass. The fetus instead develops as a plate-like structure on top of the yolk mass, and only envelopes it at a later stage.[2] A portion of the yolk mass is still present as an external or semi-external yolk sac at hatching in many groups. This form of fetal development is common in bony fish, even though their eggs can be quite small. Despite their macrolecithal structure, the small size of the eggs does not allow for direct development, and the eggs hatch to a larval stage ("fry"). In terrestrial animals with macrolecithal eggs, the large volume to surface ratio necessitates structures to aid in transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide, and for storage of waste products so that the embryo does not suffocate or get poisoned from its own waste while inside the egg, see amniote.[8]

In addition to bony fish and cephalopods, macrolecithal eggs are found in cartilaginous fish, reptiles, birds and monotreme mammals.[5] The eggs of the coelacanths can reach a size of 9 cm (3,5 in) in diameter, and the young go through full development while in the uterus, living on the copious yolk.[9]

Egg-laying reproduction

Animals are commonly classified by their manner of reproduction, at the most general level distinguishing egg-laying (Latin. oviparous) from live-bearing (Latin. viviparous).

These classifications are divided into more detail according to the development that occurs before the offspring are expelled from the adult's body. Traditionally:[10]

- Ovuliparity means the female spawns unfertilized eggs (ova), which must then be externally fertilised. Ovuliparity is typical of bony fish, anurans, echinoderms, bivalves and cnidarians. Most aquatic organisms are ovuliparous. The term is derived from the diminutive meaning "little egg".

- Oviparity is where fertilisation occurs internally and so the eggs laid by the female are zygotes (or newly developing embryos), often with important outer tissues added (for example, in a chicken egg, no part outside of the yolk originates with the zygote). Oviparity is typical of birds, reptiles, some cartilaginous fish and most arthropods. Terrestrial organisms are typically oviparous, with egg-casings that resist evaporation of moisture.

- Ovo-viviparity is where the zygote is retained in the adult's body but there are no trophic (feeding) interactions. That is, the embryo still obtains all of its nutrients from inside the egg. Most live-bearing fish, amphibians or reptiles are actually ovoviviparous. Examples include the reptile Anguis fragilis, the sea horse (where zygotes are retained in the male's ventral "marsupium"), and the frogs Rhinoderma darwinii (where the eggs develop in the vocal sac) and Rheobatrachus (where the eggs develop in the stomach).

- Histotrophic viviparity means embryos develop in the female's oviducts but obtain nutrients by consuming other ova, zygotes or sibling embryos (oophagy or adelphophagy). This intra-uterine cannibalism occurs in some sharks and in the black salamander Salamandra atra. Marsupials excrete a "uterine milk" supplementing the nourishment from the yolk sac.[11]

- Hemotrophic viviparity is where nutrients are provided from the female's blood through a designated organ. This most commonly occurs through a placenta, found in most mammals. Similar structures are found in some sharks and in the lizard Pseudomoia pagenstecheri.[12][13] In some hylid frogs, the embryo is fed by the mother through specialized gills.[14]

The term hemotropic derives from the Latin for blood-feeding, contrasted with histotrophic for tissue-feeding.[15]

Референце

- ^ D.R. Khanna (1. 1. 2005). Biology of Birds. Discovery Publishing House. стр. 130. ISBN 978-81-7141-933-3. Архивирано из оригинала 10. 5. 2016. г.

- ^ а б в г Romer, A. S. & Parsons, T. S. (1985): The Vertebrate Body. (6th ed.) Saunders, Philadelphia.

- ^ Reitzel, A.M.; Sullivan, J.C; Finnery, J.R (2006). „Qualitative shift to indirect development in the parasitic sea anemone Edwardsiella lineata”. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 46 (6): 827—837. PMID 21672788. doi:10.1093/icb/icl032

.

.

- ^ а б Barns, R.D. (1968): Invertebrate Zoology. W. B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia. 743 pages

- ^ а б в Hildebrand, M. & Gonslow, G. (2001): Analysis of Vertebrate Structure. 5th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York City

- ^ Gorbman, A. (јун 1997). „Hagfish development”. Zoological Science. 14 (3): 375—390. S2CID 198158310. doi:10.2108/zsj.14.375.

- ^ Nixon, M. & Messenger, J.B (eds) (1977): The Biology of Cephalopods. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London, pp 38–615

- ^ Stewart J. R. (1997): Morphology and evolution of the egg of oviparous amniotes. In: S. Sumida and K. Martin (ed.) Amniote Origins-Completing the Transition to Land (1): 291–326. London: Academic Press.

- ^ Fricke, H.W. & Frahm, J. (1992): Evidence for lecithotrophic viviparity in the living coelacanth. Naturwissenschaften no 79: pp. 476–479

- ^ Thierry Lodé 2001. Les stratégies de reproduction des animaux (reproduction strategies in animal kingdom). Eds Dunod Sciences, Paris

- ^ USA, David O. Norris; James A. Carr (2013). Vertebrate endocrinology. (Fifth изд.). University of Colorado at Boulder, Colorado, USA. стр. 349. ISBN 978-0123948151. Архивирано из оригинала 1. 11. 2017. г. Приступљено 25. 11. 2014.

- ^ Hamlett, William C. (1989). „Evolution and morphogenesis of the placenta in sharks”. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 252 (S2): 35—52. doi:10.1002/jez.1402520406.

- ^ Jerez, Adriana; Ramírez-Pinilla, Martha Patricia (новембар 2003). „Morphogenesis of extraembryonic membranes and placentation inMabuya mabouya (Squamata, Scincidae)”. Journal of Morphology. 258 (2): 158—178. PMID 14518010. S2CID 782433. doi:10.1002/jmor.10138.

- ^ Gorbman Peter; K.T. Pang; Martin P. Schreibman, ур. (1986). Vertebrate endocrinology : fundamentals and biomedical implications. Aubrey. Orlando: Academic Press. стр. 237. ISBN 978-0125449014. Архивирано из оригинала 1. 11. 2017. г. Приступљено 25. 11. 2014.

- ^ „Online Etymology Dictionary”. Etymonline.com. Архивирано из оригинала 2014-05-14. г. Приступљено 2013-07-27.

Литература

- James, John M.; Zeiger, Robert S.; Lester, Mitchell R.; Fasano, Mary Beth; Gern, James E.; Mansfield, Lyndon E.; Schwartz, Howard J.; Sampson, Hugh A.; Windom, Hugh H.; Machtinger, Steven B.; Lensing, Shelly (1998). „Safe administration of influenza vaccine to patients with egg allergy”. The Journal of Pediatrics. 133 (5): 624—8. PMID 9821418. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70101-5.

- Takehiko Yamamoto; Mujo Kim (1996-12-13), Hen eggs, ISBN 9780849340055

- Gilbertus. Compendium Medicine Gilberti Anglici Tam Morborum Universalium Quam Particularium Nondum Medicis Sed & Cyrurgicis Utilissimum. Lugduni: Impressum per Jacobum Sacconum, expensis Vincentii de Portonariis, 1510.

Спољашње везе

- Elmhurst College, Denaturation Protein

- Exploratorium, Anatomy of an Egg

- „Whale Shark – Cartilaginous Fish”. SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. Архивирано из оригинала 2014-06-09. г. Приступљено 2014-06-26.

- McGee, Harold J.; Long, Sharon R.; Briggs, Winslow R. (1984). „Why whip egg whites in copper bowls?”. Nature. 308 (5960): 667—8. Bibcode:1984Natur.308..667M. S2CID 4372579. doi:10.1038/308667a0.

- Arnaldo Cantani (2008). Pediatric Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

. Berlin: Springer. стр. 710–713. ISBN 978-3-540-20768-9.

. Berlin: Springer. стр. 710–713. ISBN 978-3-540-20768-9. - Dasgupta, Amitava (2019-01-01), Dasgupta, Amitava, ур., „Chapter 2 - Biotin: Pharmacology, Pathophysiology, and Assessment of Biotin Status”, Biotin and Other Interferences in Immunoassays (на језику: енглески), Elsevier, стр. 17—35, ISBN 978-0-12-816429-7, Приступљено 2020-08-27