Ромб — разлика између измена

Исправљене словне грешке |

. ознака: везе до вишезначних одредница |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{Short description|Четвороугао у коме све странице имају исту дужину}}{{рут}} |

|||

{{Инфокутија многоугао |

|||

| име = Ромб |

|||

| слика = rhombus.svg |

|||

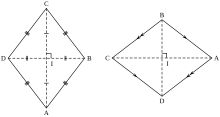

| натпис = A rhombus in two different orientations |

|||

| тип = [[quadrilateral]], [[trapezoid]], [[parallelogram]], [[kite (geometry)|kite]] |

|||

| ивице = 4 |

|||

| кокстер = {{CDD|node_1|sum|node_1}} |

|||

| симетрија = [[Dihedral symmetry|Dihedral]] (D<sub>2</sub>), [2], (*22), order 4 |

|||

| површина = <math>K = \frac{p \cdot q}{2} </math> (half the product of the diagonals) |

|||

| угао = |

|||

| двоструки = [[rectangle]] |

|||

| својства = [[convex polygon|convex]], [[isotoxal figure|isotoxal]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Ромб''' је у геометрији [[четвороугао|четвороугао]] из класе [[паралелограм]]а коме су све странице једнаких дужина. Карактерише га произвољна величина [[угао|угла]] између две његове стране, која може да варира у реалном [[Интервал (математика)|интервал]]у (0,π). Специјалан случај ромба коме су странице [[ортогоналност|нормалне]] једна на другу је [[квадрат]].<ref>Note: [[Euclid]]'s original definition and some English dictionaries' definition of rhombus excludes squares, but modern mathematicians prefer the inclusive definition.</ref><ref>{{MathWorld |urlname=Square |title=Square}} inclusive usage</ref> |

'''Ромб''' је у геометрији [[четвороугао|четвороугао]] из класе [[паралелограм]]а коме су све странице једнаких дужина. Карактерише га произвољна величина [[угао|угла]] између две његове стране, која може да варира у реалном [[Интервал (математика)|интервал]]у (0,π). Специјалан случај ромба коме су странице [[ортогоналност|нормалне]] једна на другу је [[квадрат]].<ref>Note: [[Euclid]]'s original definition and some English dictionaries' definition of rhombus excludes squares, but modern mathematicians prefer the inclusive definition.</ref><ref>{{MathWorld |urlname=Square |title=Square}} inclusive usage</ref> |

||

The rhombus is often called a "'''diamond'''", after the [[Diamonds (suit)|diamonds]] suit in [[playing card]]s which resembles the projection of an [[Octahedron#Orthogonal projections|octahedral]] [[diamond]], or a [[lozenge (shape)|lozenge]], though the former sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 60° angle (which some authors call a '''calisson''' after [[calisson|the French sweet]]<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2F_0DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA28|title = A Mathematical Space Odyssey: Solid Geometry in the 21st Century|isbn = 9781614442165|last1 = Alsina|first1 = Claudi|last2 = Nelsen|first2 = Roger B.|date = 31 December 2015}}</ref> – also see [[Polyiamond]]), and the latter sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 45° angle. |

|||

== Формуле == |

== Формуле == |

||

| Ред 34: | Ред 51: | ||

Углови између дијагонала ромба су прави тј. једнаки 90°. |

Углови између дијагонала ромба су прави тј. једнаки 90°. |

||

==Etymology== |

|||

The word "rhombus" comes from {{lang-grc|ῥόμβος|rhombos}}, meaning something that spins,<ref>[https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dr%28o%2Fmbos {{lang|grc|ῥόμβος}}] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131108114843/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dr%28o%2Fmbos |date=2013-11-08 }}, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', on Perseus</ref> which derives from the verb {{wikt-lang|grc|ῥέμβω}}, <small>romanized:</small> {{transl|grc|rhémbō}}, meaning "to turn round and round."<ref>[https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dr%28e%2Fmbw ρέμβω] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131108114840/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dr%28e%2Fmbw |date=2013-11-08 }}, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', on Perseus</ref> The word was used both by [[Euclid]] and [[Archimedes]], who used the term "solid rhombus" for a [[bicone]], two right circular [[cone]]s sharing a common base.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.pballew.net/rhomb |title=The Origin of Rhombus |access-date=2005-01-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402143657/http://www.pballew.net/rhomb |archive-date=2015-04-02 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

The surface we refer to as ''rhombus'' today is a [[cross section (geometry)|cross section]] of the bicone on a plane through the apexes of the two cones. |

|||

==Characterizations== |

|||

A [[simple polygon|simple]] (non-[[list of self-intersecting polygons|self-intersecting]]) quadrilateral is a rhombus [[if and only if]] it is any one of the following:<ref>Zalman Usiskin and Jennifer Griffin, "[https://books.google.com/books?id=ff0nDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=rhombus&f=false The Classification of Quadrilaterals. A Study of Definition] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200226195300/https://books.google.com/books?id=ff0nDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=rhombus&f=false |date=2020-02-26 }}", Information Age Publishing, 2008, pp. 55-56.</ref><ref>Owen Byer, Felix Lazebnik and [[Deirdre Smeltzer]], ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=W4acIu4qZvoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=rhombus&f=false Methods for Euclidean Geometry] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190901191543/https://books.google.com/books?id=W4acIu4qZvoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=rhombus&f=false |date=2019-09-01 }}'', Mathematical Association of America, 2010, p. 53.</ref> |

|||

*a [[parallelogram]] in which a [[diagonal]] bisects an [[Internal and external angle|interior angle]] |

|||

*a parallelogram in which at least two consecutive sides are equal in length |

|||

*a parallelogram in which the diagonals are perpendicular (an [[orthodiagonal]] parallelogram) |

|||

*a quadrilateral with four sides of equal length (by definition) |

|||

*a quadrilateral in which the diagonals are [[perpendicular]] and [[Bisection|bisect]] each other |

|||

*a quadrilateral in which each diagonal bisects two opposite interior angles |

|||

*a quadrilateral ''ABCD'' possessing a point ''P'' in its plane such that the four triangles ''ABP'', ''BCP'', ''CDP'', and ''DAP'' are all [[Congruence (geometry)|congruent]]<ref>Paris Pamfilos (2016), "A Characterization of the Rhombus", ''[[Forum Geometricorum]]'' '''16''', pp. 331–336, [http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2016volume16/FG201640.pdf] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161023135753/http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2016volume16/FG201640.pdf |date=2016-10-23 }}</ref> |

|||

*a quadrilateral ''ABCD'' in which the [[Incircle and excircles of a triangle|incircle]]s in triangles ''ABC'', ''BCD'', ''CDA'' and ''DAB'' have a common point<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://imomath.com/othercomp/Bra/BraMO04.pdf |title=IMOmath, "26-th Brazilian Mathematical Olympiad 2004" |access-date=2020-01-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161018164829/http://imomath.com/othercomp/Bra/BraMO04.pdf |archive-date=2016-10-18 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Basic properties== |

|||

Every rhombus has two [[diagonal]]s connecting pairs of opposite vertices, and two pairs of parallel sides. Using [[congruence (geometry)|congruent]] [[triangle]]s, one can [[mathematical proof|prove]] that the rhombus is [[symmetry|symmetric]] across each of these diagonals. It follows that any rhombus has the following properties: |

|||

* Opposite [[angle]]s of a rhombus have equal measure. |

|||

* The two diagonals of a rhombus are [[perpendicular]]; that is, a rhombus is an [[orthodiagonal quadrilateral]]. |

|||

* Its diagonals bisect opposite angles. |

|||

The first property implies that every rhombus is a [[parallelogram]]. A rhombus therefore has all of the [[Parallelogram#Properties|properties of a parallelogram]]: for example, opposite sides are parallel; adjacent angles are [[supplementary angles|supplementary]]; the two diagonals [[bisection|bisect]] one another; any line through the midpoint bisects the area; and the sum of the squares of the sides equals the sum of the squares of the diagonals (the [[parallelogram law]]). Thus denoting the common side as ''a'' and the diagonals as ''p'' and ''q'', in every rhombus |

|||

:<math>\displaystyle 4a^2=p^2+q^2.</math> |

|||

Not every parallelogram is a rhombus, though any parallelogram with perpendicular diagonals (the second property) is a rhombus. In general, any quadrilateral with perpendicular diagonals, one of which is a line of symmetry, is a [[kite (geometry)|kite]]. Every rhombus is a kite, and any quadrilateral that is both a kite and parallelogram is a rhombus. |

|||

A rhombus is a [[tangential quadrilateral]].<ref name=Mathworld>{{mathworld |urlname=Rhombus |title=Rhombus}}</ref> That is, it has an [[inscribed figure|inscribed circle]] that is tangent to all four sides. |

|||

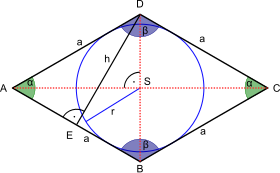

[[File:Rhombus1.svg|thumb|280px|A rhombus. Each angle marked with a black dot is a right angle. The height ''h'' is the perpendicular distance between any two non-adjacent sides, which equals the diameter of the circle inscribed. The diagonals of lengths ''p'' and ''q'' are the red dotted line segments.]] |

|||

==Diagonals== |

|||

The length of the diagonals ''p = AC'' and ''q = BD'' can be expressed in terms of the rhombus side ''a'' and one vertex angle ''α'' as |

|||

:<math>p=a\sqrt{2+2\cos{\alpha}}</math> |

|||

and |

|||

:<math>q=a\sqrt{2-2\cos{\alpha}}.</math> |

|||

These formulas are a direct consequence of the [[law of cosines]]. |

|||

==Inradius== |

|||

The inradius (the radius of a circle [[inscribed]] in the rhombus), denoted by {{math|''r''}}, can be expressed in terms of the diagonals {{math|''p''}} and {{math|''q''}} as<ref name=Mathworld/> |

|||

:<math>r = \frac{p \cdot q}{2\sqrt{p^2+q^2}},</math> |

|||

or in terms of the side length {{math|''a''}} and any vertex angle {{math|''α''}} or {{math|''β''}} as |

|||

:<math>r = \frac{a\sin\alpha}{2} = \frac{a\sin\beta}{2}.</math> |

|||

==Area== |

|||

As for all [[parallelogram]]s, the [[area]] ''K'' of a rhombus is the product of its [[Base (geometry)|base]] and its [[height]] (''h''). The base is simply any side length ''a'': |

|||

:<math>K = a \cdot h .</math> |

|||

The area can also be expressed as the [[Edge (geometry)|base]] [[Square (algebra)|squared]] times the sine of any angle: |

|||

:<math>K = a^2 \cdot \sin \alpha = a^2 \cdot \sin \beta ,</math> |

|||

or in terms of the height and a [[Vertex (geometry)|vertex]] [[angle]]: |

|||

:<math>K=\frac{h^2}{\sin\alpha} ,</math> |

|||

or as half the product of the [[diagonal]]s ''p'', ''q'': |

|||

:<math>K = \frac{p \cdot q}{2} ,</math> |

|||

or as the [[semiperimeter]] times the [[radius]] of the [[circle]] [[Inscribed figure|inscribed]] in the rhombus (inradius): |

|||

:<math>K = 2a \cdot r .</math> |

|||

Another way, in common with parallelograms, is to consider two adjacent sides as vectors, forming a [[bivector]], so the area is the magnitude of the bivector (the magnitude of the vector product of the two vectors), which is the [[determinant]] of the two vectors' Cartesian coordinates: ''K'' = ''x''<sub>1</sub>''y''<sub>2</sub> – ''x''<sub>2</sub>''y''<sub>1</sub>.<ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XghF70fqkY WildLinAlg episode 4] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170205162901/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XghF70fqkY |date=2017-02-05 }}, Norman J Wildberger, Univ. of New South Wales, 2010, lecture via youtube</ref> |

|||

==Cartesian equation== |

|||

The sides of a rhombus centered at the origin, with diagonals each falling on an axis, consist of all points (''x, y'') satisfying |

|||

:<math>\left|\frac{x}{a}\right|\! + \left|\frac{y}{b}\right|\! = 1.</math> |

|||

The vertices are at <math>(\pm a, 0)</math> and <math>(0, \pm b).</math> This is a special case of the [[superellipse]], with exponent 1. |

|||

==Other properties== |

|||

*One of the five 2D [[lattice (group)|lattice]] types is the rhombic lattice, also called [[centered rectangular lattice]]. |

|||

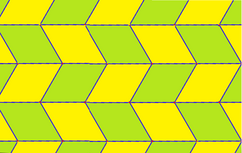

* Identical rhombi can tile the 2D plane in three different ways, including, for the 60° rhombus, the [[rhombille tiling]]. |

|||

** |

|||

{| class=wikitable |

|||

!colspan=2|As topological [[square tiling]]s |

|||

!As 30-60 degree [[rhombille]] tiling |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[File:Isohedral tiling p4-55.png|240px]] |

|||

|[[File:Isohedral tiling p4-51c.png|242px]] |

|||

|[[File:Rhombic star tiling.png|154px]] |

|||

|} |

|||

* Three-dimensional analogues of a rhombus include the [[bipyramid]] and the [[bicone]]. |

|||

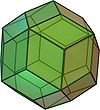

* Several [[polyhedra]] have rhombic faces, such as the [[rhombic dodecahedron]] and the [[trapezo-rhombic dodecahedron]]. |

|||

{| class=wikitable |

|||

|+<big>Some polyhedra with all rhombic faces</big> |

|||

! colspan="2" |Isohedral polyhedra |

|||

! colspan="3" |Not isohedral polyhedra |

|||

|- |

|||

!Identical rhombi |

|||

! colspan="2" |Identical golden rhombi |

|||

!Two types of rhombi |

|||

!Three types of rhombi |

|||

|- align="center" |

|||

|[[File:Rhombicdodecahedron.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|[[File:Rhombictriacontahedron.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|[[File:Rhombic icosahedron.png|100px]] |

|||

|[[File:Rhombic enneacontahedron.png|100px]] |

|||

|[[File:Rhombohedron.svg|100px]] |

|||

|- align="center" |

|||

![[Rhombic dodecahedron]] |

|||

![[Rhombic triacontahedron]] |

|||

![[Rhombic icosahedron]] |

|||

![[Rhombic enneacontahedron]] |

|||

![[Rhombohedron]] |

|||

|} |

|||

== Референце == |

== Референце == |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

== Литература == |

|||

{{Refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* {{cite book | author= Anthony Pugh | year= 1976 | title= Polyhedra: A visual approach | publisher= University of California Press Berkeley | location= California | isbn= 0-520-03056-7 }} |

|||

* Љиљана Петрушевски - Полиедри |

|||

* Cromwell, P.;''Polyhedra'', CUP hbk (1997), pbk. (1999). |

|||

* {{cite book| author1 = Grünbaum, B. | authorlink1 = Branko Grünbaum | chapter = Polyhedra with Hollow Faces |

|||

| editor1 = Tibor Bisztriczky | editor2 = Peter McMullen |

|||

| editor3 = Rolf Schneider |display-editors = 3 | editor4 = A Weiss |

|||

| title = Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Polytopes: Abstract, Convex and Computational |

|||

| year = 1994| publisher = Springer | location = |isbn= 978-94-010-4398-4| pages = 43–70 |

|||

| url = http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-011-0924-6_3}} |

|||

* Grünbaum, B.; Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra? ''Discrete and comput. geom: the Goodman-Pollack festschrift'', ed. Aronov et al. Springer (2003) pp. 461–488.'' ([http://www.math.washington.edu/~grunbaum/Your%20polyhedra-my%20polyhedra.pdf pdf] {{Wayback|url=http://www.math.washington.edu/~grunbaum/Your%20polyhedra-my%20polyhedra.pdf |date=20160803160413 }}) |

|||

* [[Joseph Louis François Bertrand|Bertrand, J.]] (1858). Note sur la théorie des polyèdres réguliers, ''Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Sciences'', '''46''', pp. 79–82. |

|||

* Haeckel, E. (1904). ''[[Kunstformen der Natur]]''. Available as Haeckel, E. ''Art forms in nature'', Prestel USA (1998), {{isbn|3-7913-1990-6}}, or online at https://web.archive.org/web/20090627082453/http://caliban.mpiz-koeln.mpg.de/~stueber/haeckel/kunstformen/natur.html |

|||

*Smith, J. V. (1982). ''Geometrical And Structural Crystallography''. John Wiley and Sons. |

|||

* [[Duncan MacLaren Young Sommerville|Sommerville, D. M. Y.]] (1930). ''An Introduction to the Geometry of n Dimensions.'' E. P. Dutton, New York. (Dover Publications edition, 1958). Chapter X: The Regular Polytopes. |

|||

*[[H.S.M. Coxeter|Coxeter, H.S.M.]]; Regular Polytopes (third edition). Dover Publications Inc. {{isbn|0-486-61480-8}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |authorlink=Hassler Whitney |first=Hassler |last=Whitney |title=Congruent graphs and the connectivity of graphs |url=https://archive.org/details/sim_american-journal-of-mathematics_1932-01_54_1/page/150 |journal=Amer. J. Math. |volume=54 |issue=1 |pages=150–168 |year=1932 |jstor=2371086 |doi=10.2307/2371086|hdl=10338.dmlcz/101067 }} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last1 = Blind | first1 = Roswitha |

|||

| last2 = Mani-Levitska | first2 = Peter |

|||

| doi = 10.1007/BF01830678 |

|||

| issue = 2–3 |

|||

| journal = [[Aequationes Mathematicae]] |

|||

| mr = 921106 |

|||

| pages = 287–297 |

|||

| title = Puzzles and polytope isomorphisms |

|||

| volume = 34 |

|||

| year = 1987}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last = Kalai | first = Gil | authorlink = Gil Kalai |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/0097-3165(88)90064-7 |

|||

| issue = 2 |

|||

| journal = [[Journal of Combinatorial Theory]] | series = Ser. A |

|||

| mr = 964396 |

|||

| pages = 381–383 |

|||

| title = A simple way to tell a simple polytope from its graph |

|||

| volume = 49 |

|||

| year = 1988}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |first=Volker |last=Kaibel |first2=Alexander |last2=Schwartz |url=http://eprintweb.org/S/authors/All/ka/Kaibel/16 |title=On the Complexity of Polytope Isomorphism Problems |journal=[[Graphs and Combinatorics]] |volume=19 |issue=2 |pages=215–230 |year=2003 |arxiv=math/0106093 |doi=10.1007/s00373-002-0503-y |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150721175904/http://eprintweb.org/S/authors/All/ka/Kaibel/16 |archivedate=2015-07-21 }} |

|||

* {{Cite book | last1 = Büeler | first1 = B. | last2 = Enge | first2 = A. | last3 = Fukuda | first3 = K. | doi = 10.1007/978-3-0348-8438-9_6 | chapter = Exact Volume Computation for Polytopes: A Practical Study | title = Polytopes — Combinatorics and Computation | pages = 131 | year = 2000 | isbn = 978-3-7643-6351-2 | pmid = | pmc = }} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last = Yao | first = Andrew Chi Chih | authorlink = Andrew Yao |

|||

| doi = 10.1145/322276.322289 |

|||

| issue = 4 |

|||

| journal = [[Journal of the ACM]] |

|||

| mr = 677089 |

|||

| pages = 780–787 |

|||

| title = A lower bound to finding convex hulls |

|||

| volume = 28 |

|||

| year = 1981}}; {{citation |

|||

| last = Ben-Or | first = Michael |

|||

| contribution = Lower Bounds for Algebraic Computation Trees |

|||

| doi = 10.1145/800061.808735 |

|||

| pages = 80–86 |

|||

| title = Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC '83) |

|||

| year = 1983}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last1 = Cundy | first1 = H. Martyn | author1-link = Martyn Cundy |

|||

| last2 = Rollett | first2 = A. P. |

|||

| edition = 2nd |

|||

| location = Oxford |

|||

| mr = 0124167 |

|||

| publisher = Clarendon Press |

|||

| title = Mathematical Models |

|||

| year = 1961}}. |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last1 = Gailiunas | first1 = P. |

|||

| last2 = Sharp | first2 = J. |

|||

| doi = 10.1080/00207390500064049 |

|||

| issue = 6 |

|||

| journal = International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology |

|||

| pages = 617–642 |

|||

| title = Duality of polyhedra |

|||

| volume = 36 |

|||

| year = 2005}}. |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last = Grünbaum | first = Branko | authorlink = Branko Grünbaum |

|||

| editor1-last = Aronov | editor1-first = Boris | editor1-link = Boris Aronov |

|||

| editor2-last = Basu | editor2-first = Saugata |

|||

| editor3-last = Pach | editor3-first = János | editor3-link = János Pach |

|||

| editor4-last = Sharir | editor4-first = Micha | editor4-link = Micha Sharir |

|||

| contribution = Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra? |

|||

| doi = 10.1007/978-3-642-55566-4_21 |

|||

| mr = 2038487 |

|||

| pages = 461–488 |

|||

| publisher = Springer | location = Berlin |

|||

| series = Algorithms and Combinatorics |

|||

| title = Discrete and Computational Geometry: The Goodman–Pollack Festschrift |

|||

| volume = 25 |

|||

| year = 2003| citeseerx = 10.1.1.102.755| isbn = 978-3-642-62442-1 }}. |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last = Grünbaum | first = Branko | authorlink = Branko Grünbaum |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/j.disc.2005.09.037 |

|||

| issue = 3–5 |

|||

| journal = [[Discrete Mathematics (journal)|Discrete Mathematics]] |

|||

| mr = 2287486 |

|||

| pages = 445–463 |

|||

| title = Graphs of polyhedra; polyhedra as graphs |

|||

| volume = 307 |

|||

| year = 2007}}. |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last1 = Grünbaum | first1 = Branko | author1-link = Branko Grünbaum |

|||

| last2 = Shephard | first2 = G. C. | author2-link = Geoffrey Colin Shephard |

|||

| editor-last = Senechal | editor-first = Marjorie | editor-link = Marjorie Senechal |

|||

| contribution = Duality of polyhedra |

|||

| doi = 10.1007/978-0-387-92714-5_15 |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-387-92713-8 |

|||

| mr = 3077226 |

|||

| pages = 211–216 |

|||

| publisher = Springer | location = New York |

|||

| title = Shaping Space: Exploring polyhedra in nature, art, and the geometrical imagination |

|||

| year = 2013}}. |

|||

* {{citation| first=Magnus | last=Wenninger | authorlink=Magnus Wenninger | title=Dual Models | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1983 | isbn=0-521-54325-8 | mr = 0730208}}. |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

| last1 = Barvinok | first1 = Alexander |

|||

| isbn = 0821829688 |

|||

| publisher = American Mathematical Soc. | location = Providence |

|||

| title = A course in convexity |

|||

| year = 2002}} |

|||

* de Villiers, Michael, "Equiangular cyclic and equilateral circumscribed polygons", ''[[Mathematical Gazette]]'' 95, March 2011, 102-107. |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

Верзија на датум 20. јул 2022. у 21:10

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

| Ромб | |

|---|---|

A rhombus in two different orientations | |

| Тип | quadrilateral, trapezoid, parallelogram, kite |

| Ивице и темена | 4 |

| Дијаграм Кокстера | |

| Симетрична група | Dihedral (D2), [2], (*22), order 4 |

| Површина | (half the product of the diagonals) |

| Двоструки многоугао | rectangle |

| Својства | convex, isotoxal |

Ромб је у геометрији четвороугао из класе паралелограма коме су све странице једнаких дужина. Карактерише га произвољна величина угла између две његове стране, која може да варира у реалном интервалу (0,π). Специјалан случај ромба коме су странице нормалне једна на другу је квадрат.[1][2]

The rhombus is often called a "diamond", after the diamonds suit in playing cards which resembles the projection of an octahedral diamond, or a lozenge, though the former sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 60° angle (which some authors call a calisson after the French sweet[3] – also see Polyiamond), and the latter sometimes refers specifically to a rhombus with a 45° angle.

Формуле

| Висина | |

| Обим | |

| Површина | |

| Дијагонале | |

| Полупречник уписане кружнице |

Углови

Из једнакости страна следи да су наспрамни углови ромба једнаки, што значи да постоје само две различите величине углова између страна ромба: α и β.

Са друге стране правило о збиру углова у четвороуглу једнозначно одређује вредност величине другог угла, уколико је први познат, те је ромб одређен само са дужином странице и једним углом:

Углови између дијагонала ромба су прави тј. једнаки 90°.

Etymology

The word "rhombus" comes from стгрч. ῥόμβος, meaning something that spins,[4] which derives from the verb ῥέμβω, romanized: rhémbō, meaning "to turn round and round."[5] The word was used both by Euclid and Archimedes, who used the term "solid rhombus" for a bicone, two right circular cones sharing a common base.[6]

The surface we refer to as rhombus today is a cross section of the bicone on a plane through the apexes of the two cones.

Characterizations

A simple (non-self-intersecting) quadrilateral is a rhombus if and only if it is any one of the following:[7][8]

- a parallelogram in which a diagonal bisects an interior angle

- a parallelogram in which at least two consecutive sides are equal in length

- a parallelogram in which the diagonals are perpendicular (an orthodiagonal parallelogram)

- a quadrilateral with four sides of equal length (by definition)

- a quadrilateral in which the diagonals are perpendicular and bisect each other

- a quadrilateral in which each diagonal bisects two opposite interior angles

- a quadrilateral ABCD possessing a point P in its plane such that the four triangles ABP, BCP, CDP, and DAP are all congruent[9]

- a quadrilateral ABCD in which the incircles in triangles ABC, BCD, CDA and DAB have a common point[10]

Basic properties

Every rhombus has two diagonals connecting pairs of opposite vertices, and two pairs of parallel sides. Using congruent triangles, one can prove that the rhombus is symmetric across each of these diagonals. It follows that any rhombus has the following properties:

- Opposite angles of a rhombus have equal measure.

- The two diagonals of a rhombus are perpendicular; that is, a rhombus is an orthodiagonal quadrilateral.

- Its diagonals bisect opposite angles.

The first property implies that every rhombus is a parallelogram. A rhombus therefore has all of the properties of a parallelogram: for example, opposite sides are parallel; adjacent angles are supplementary; the two diagonals bisect one another; any line through the midpoint bisects the area; and the sum of the squares of the sides equals the sum of the squares of the diagonals (the parallelogram law). Thus denoting the common side as a and the diagonals as p and q, in every rhombus

Not every parallelogram is a rhombus, though any parallelogram with perpendicular diagonals (the second property) is a rhombus. In general, any quadrilateral with perpendicular diagonals, one of which is a line of symmetry, is a kite. Every rhombus is a kite, and any quadrilateral that is both a kite and parallelogram is a rhombus.

A rhombus is a tangential quadrilateral.[11] That is, it has an inscribed circle that is tangent to all four sides.

Diagonals

The length of the diagonals p = AC and q = BD can be expressed in terms of the rhombus side a and one vertex angle α as

and

These formulas are a direct consequence of the law of cosines.

Inradius

The inradius (the radius of a circle inscribed in the rhombus), denoted by r, can be expressed in terms of the diagonals p and q as[11]

or in terms of the side length a and any vertex angle α or β as

Area

As for all parallelograms, the area K of a rhombus is the product of its base and its height (h). The base is simply any side length a:

The area can also be expressed as the base squared times the sine of any angle:

or in terms of the height and a vertex angle:

or as half the product of the diagonals p, q:

or as the semiperimeter times the radius of the circle inscribed in the rhombus (inradius):

Another way, in common with parallelograms, is to consider two adjacent sides as vectors, forming a bivector, so the area is the magnitude of the bivector (the magnitude of the vector product of the two vectors), which is the determinant of the two vectors' Cartesian coordinates: K = x1y2 – x2y1.[12]

Cartesian equation

The sides of a rhombus centered at the origin, with diagonals each falling on an axis, consist of all points (x, y) satisfying

The vertices are at and This is a special case of the superellipse, with exponent 1.

Other properties

- One of the five 2D lattice types is the rhombic lattice, also called centered rectangular lattice.

- Identical rhombi can tile the 2D plane in three different ways, including, for the 60° rhombus, the rhombille tiling.

| As topological square tilings | As 30-60 degree rhombille tiling | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

- Three-dimensional analogues of a rhombus include the bipyramid and the bicone.

- Several polyhedra have rhombic faces, such as the rhombic dodecahedron and the trapezo-rhombic dodecahedron.

| Isohedral polyhedra | Not isohedral polyhedra | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identical rhombi | Identical golden rhombi | Two types of rhombi | Three types of rhombi | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Rhombic dodecahedron | Rhombic triacontahedron | Rhombic icosahedron | Rhombic enneacontahedron | Rhombohedron |

Референце

- ^ Note: Euclid's original definition and some English dictionaries' definition of rhombus excludes squares, but modern mathematicians prefer the inclusive definition.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. „Square”. MathWorld. inclusive usage

- ^ Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger B. (31. 12. 2015). A Mathematical Space Odyssey: Solid Geometry in the 21st Century. ISBN 9781614442165.

- ^ ῥόμβος Архивирано 2013-11-08 на сајту Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ρέμβω Архивирано 2013-11-08 на сајту Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ „The Origin of Rhombus”. Архивирано из оригинала 2015-04-02. г. Приступљено 2005-01-25.

- ^ Zalman Usiskin and Jennifer Griffin, "The Classification of Quadrilaterals. A Study of Definition Архивирано 2020-02-26 на сајту Wayback Machine", Information Age Publishing, 2008, pp. 55-56.

- ^ Owen Byer, Felix Lazebnik and Deirdre Smeltzer, Methods for Euclidean Geometry Архивирано 2019-09-01 на сајту Wayback Machine, Mathematical Association of America, 2010, p. 53.

- ^ Paris Pamfilos (2016), "A Characterization of the Rhombus", Forum Geometricorum 16, pp. 331–336, [1] Архивирано 2016-10-23 на сајту Wayback Machine

- ^ „IMOmath, "26-th Brazilian Mathematical Olympiad 2004"” (PDF). Архивирано (PDF) из оригинала 2016-10-18. г. Приступљено 2020-01-06.

- ^ а б Weisstein, Eric W. „Rhombus”. MathWorld.

- ^ WildLinAlg episode 4 Архивирано 2017-02-05 на сајту Wayback Machine, Norman J Wildberger, Univ. of New South Wales, 2010, lecture via youtube

Литература

- Anthony Pugh (1976). Polyhedra: A visual approach. California: University of California Press Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-03056-7.

- Љиљана Петрушевски - Полиедри

- Cromwell, P.;Polyhedra, CUP hbk (1997), pbk. (1999).

- Grünbaum, B. (1994). „Polyhedra with Hollow Faces”. Ур.: Tibor Bisztriczky; Peter McMullen; Rolf Schneider; et al. Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Polytopes: Abstract, Convex and Computational. Springer. стр. 43—70. ISBN 978-94-010-4398-4.

- Grünbaum, B.; Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra? Discrete and comput. geom: the Goodman-Pollack festschrift, ed. Aronov et al. Springer (2003) pp. 461–488. (pdf Архивирано на сајту Wayback Machine (3. август 2016))

- Bertrand, J. (1858). Note sur la théorie des polyèdres réguliers, Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 46, pp. 79–82.

- Haeckel, E. (1904). Kunstformen der Natur. Available as Haeckel, E. Art forms in nature, Prestel USA (1998), ISBN 3-7913-1990-6, or online at https://web.archive.org/web/20090627082453/http://caliban.mpiz-koeln.mpg.de/~stueber/haeckel/kunstformen/natur.html

- Smith, J. V. (1982). Geometrical And Structural Crystallography. John Wiley and Sons.

- Sommerville, D. M. Y. (1930). An Introduction to the Geometry of n Dimensions. E. P. Dutton, New York. (Dover Publications edition, 1958). Chapter X: The Regular Polytopes.

- Coxeter, H.S.M.; Regular Polytopes (third edition). Dover Publications Inc. ISBN 0-486-61480-8

- Whitney, Hassler (1932). „Congruent graphs and the connectivity of graphs”. Amer. J. Math. 54 (1): 150—168. JSTOR 2371086. doi:10.2307/2371086. hdl:10338.dmlcz/101067.

- Blind, Roswitha; Mani-Levitska, Peter (1987), „Puzzles and polytope isomorphisms”, Aequationes Mathematicae, 34 (2–3): 287—297, MR 921106, doi:10.1007/BF01830678

- Kalai, Gil (1988), „A simple way to tell a simple polytope from its graph”, Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Ser. A, 49 (2): 381—383, MR 964396, doi:10.1016/0097-3165(88)90064-7

- Kaibel, Volker; Schwartz, Alexander (2003). „On the Complexity of Polytope Isomorphism Problems”. Graphs and Combinatorics. 19 (2): 215—230. arXiv:math/0106093

. doi:10.1007/s00373-002-0503-y. Архивирано из оригинала 2015-07-21. г.

. doi:10.1007/s00373-002-0503-y. Архивирано из оригинала 2015-07-21. г. - Büeler, B.; Enge, A.; Fukuda, K. (2000). „Exact Volume Computation for Polytopes: A Practical Study”. Polytopes — Combinatorics and Computation. стр. 131. ISBN 978-3-7643-6351-2. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-8438-9_6.

- Yao, Andrew Chi Chih (1981), „A lower bound to finding convex hulls”, Journal of the ACM, 28 (4): 780—787, MR 677089, doi:10.1145/322276.322289; Ben-Or, Michael (1983), „Lower Bounds for Algebraic Computation Trees”, Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC '83), стр. 80—86, doi:10.1145/800061.808735

- Cundy, H. Martyn; Rollett, A. P. (1961), Mathematical Models (2nd изд.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, MR 0124167.

- Gailiunas, P.; Sharp, J. (2005), „Duality of polyhedra”, International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 36 (6): 617—642, doi:10.1080/00207390500064049.

- Grünbaum, Branko (2003), „Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra?”, Ур.: Aronov, Boris; Basu, Saugata; Pach, János; Sharir, Micha, Discrete and Computational Geometry: The Goodman–Pollack Festschrift, Algorithms and Combinatorics, 25, Berlin: Springer, стр. 461—488, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.102.755

, ISBN 978-3-642-62442-1, MR 2038487, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55566-4_21.

, ISBN 978-3-642-62442-1, MR 2038487, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55566-4_21. - Grünbaum, Branko (2007), „Graphs of polyhedra; polyhedra as graphs”, Discrete Mathematics, 307 (3–5): 445—463, MR 2287486, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2005.09.037.

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (2013), „Duality of polyhedra”, Ур.: Senechal, Marjorie, Shaping Space: Exploring polyhedra in nature, art, and the geometrical imagination, New York: Springer, стр. 211—216, ISBN 978-0-387-92713-8, MR 3077226, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-92714-5_15.

- Wenninger, Magnus (1983), Dual Models, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-54325-8, MR 0730208.

- Barvinok, Alexander (2002), A course in convexity, Providence: American Mathematical Soc., ISBN 0821829688

- de Villiers, Michael, "Equiangular cyclic and equilateral circumscribed polygons", Mathematical Gazette 95, March 2011, 102-107.