Размера (географија) — разлика између измена

. |

|||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

[[Датотека:Scales in miles and meters.jpg|мини| |

[[Датотека:Scales in miles and meters.jpg|мини|250п|<center>Размере у метрима и миљама.]] |

||

'''Размера''' или '''размер''' је однос између дужине неке [[дуж]]и представљене на [[цртеж]]у ([[план]]у, [[карта|карти]]) и њој одговарајуће дужине у природи која је на [[цртеж]]у хоризонтално пројектована. |

|||

Размера се обично представља [[дељење|количником]] 1:-{n}-, где број -{n}- означава колико пута је пута дужина у природи -{n}- смањена (или ређе, повећана). То је бројна размера, која се увек изражава у виду разломка, код кога је бројилац једнак јединици. |

'''Размера''' или '''размер''' је однос између дужине неке [[дуж]]и представљене на [[цртеж]]у ([[план]]у, [[карта|карти]]) и њој одговарајуће дужине у природи која је на [[цртеж]]у хоризонтално пројектована. Размера се обично представља [[дељење|количником]] 1:-{n}-, где број -{n}- означава колико пута је пута дужина у природи -{n}- смањена (или ређе, повећана). То је бројна размера, која се увек изражава у виду разломка, код кога је бројилац једнак јединици. |

||

При упоређењу две размере (-{R}-<sub>1</sub>, -{R}-<sub>2</sub>) за једну се каже да је крупнија ако је њен број -{n}-<sub>1</sub> мањи од броја -{n}-<sub>2</sub> друге размере, и обратно, за другу размеру -{R}-<sub>2</sub> каже се да је ситнија ако је -{n}-<sub>2</sub> > -{n}-<sub>1</sub>. |

При упоређењу две размере (-{R}-<sub>1</sub>, -{R}-<sub>2</sub>) за једну се каже да је крупнија ако је њен број -{n}-<sub>1</sub> мањи од броја -{n}-<sub>2</sub> друге размере, и обратно, за другу размеру -{R}-<sub>2</sub> каже се да је ситнија ако је -{n}-<sub>2</sub> > -{n}-<sub>1</sub>. Избор размере зависи од: намене [[цртеж]]а ([[план]]а), од условљене тачности тог цртежа; од врсте, величине и облика цртежа, као и од међусобног односа објеката које треба представити. Размера представљена у графичком облику назива се [[размерник]]. |

||

{{rut}} |

|||

If the region of the map is small enough to ignore Earth's curvature, such as in a town plan, then a single value can be used as the scale without causing measurement errors. In maps covering larger areas, or the whole Earth, the map's scale may be less useful or even useless in measuring distances. The map projection becomes critical in understanding how scale varies throughout the map.<ref name=snyder>{{cite book | author=Snyder, John P. | title=Map Projections - A Working Manual. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1395 | publisher =United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. | year=1987}}This paper can be downloaded from [https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/pubs/pp/pp1395 USGS pages.] It gives full details of most projections, together with introductory sections, but it does not derive any of the projections from first principles. Derivation of all the formulae for the Mercator projections may be found in ''The Mercator Projections''.</ref><ref name=flattening>''Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections'', John P. Snyder, 1993, pp. 5-8, {{ISBN|0-226-76747-7}}. This is a survey of virtually all known projections from antiquity to 1993.</ref> When scale varies noticeably, it can be accounted for as the scale factor. [[Tissot's indicatrix]] is often used to illustrate the variation of point scale across a map. |

|||

== Историја == |

|||

Избор размере зависи од: намене [[цртеж]]а ([[план]]а), од условљене тачности тог цртежа; од врсте, величине и облика цртежа, као и од међусобног односа објеката које треба представити. |

|||

The foundations for quantitative map scaling goes back to [[Chinese cartography|ancient China]] with textual evidence that the idea of map scaling was understood by the second century BC. Ancient Chinese surveyors and cartographers had ample technical resources used to produce maps such as [[counting rods]], [[carpenter's square]]'s, [[Plumb bob|plumb lines]], [[Compass (drawing tool)|compasses]] for drawing circles, and sighting tubes for measuring inclination. Reference frames postulating a nascent coordinate system for identifying locations were hinted by ancient Chinese astronomers that divided the sky into various sectors or lunar lodges.<ref name="Selin 2008 567">{{Cite book |title=Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures |last=Selin |first= Helaine |publisher=Springer |year=2008 |isbn= 978-1402049606 |publication-date=March 17, 2008 |page=567}}</ref> |

|||

Размера представљена у графичком облику назива се [[размерник]]. |

|||

The Chinese cartographer and geographer [[Pei Xiu]] of the Three Kingdoms period created a set of large-area maps that were drawn to scale. He produced a set of principles that stressed the importance of consistent scaling, directional measurements, and adjustments in land measurements in the terrain that was being mapped.<ref name="Selin 2008 567"/> |

|||

== Large-scale maps with curvature neglected== |

|||

The region over which the earth can be regarded as flat depends on the accuracy of the [[surveying|survey]] measurements. If measured only to the nearest metre, then [[curvature of the earth]] is undetectable over a meridian distance of about {{Convert|100|km}} and over an east-west line of about 80 km (at a [[latitude]] of 45 degrees). If surveyed to the nearest {{Convert|1|mm|inch}}, then curvature is undetectable over a [[meridian arc|meridian]] distance of about 10 km and over an east-west line of about 8 km.<ref name=merc>{{citation|first=Peter |

|||

|last=Osborne |

|||

|title=The Mercator Projections |

|||

|year=2013 |

|||

|doi=10.5281/zenodo.35392 |

|||

|postscript=. (Supplements: [https://zenodo.org/record/35561 Maxima files] and [https://zenodo.org/record/35562 Latex code and figures]) |

|||

}}</ref> Thus a plan of [[New York City]] accurate to one metre or a building site plan accurate to one millimetre would both satisfy the above conditions for the neglect of curvature. They can be treated by plane surveying and mapped by scale drawings in which any two points at the same distance on the drawing are at the same distance on the ground. True ground distances are calculated by measuring the distance on the map and then multiplying by the [[Multiplicative inverse|inverse]] of the scale fraction or, equivalently, simply using dividers to transfer the separation between the points on the map to a [[bar scale]] on the map. |

|||

== Point scale (or particular scale){{anchor|Factor}}== |

|||

As proved by [[Gauss]]’s ''[[Theorema Egregium]]'', a sphere (or ellipsoid) cannot be projected onto a [[Plane (geometry)|plane]] without distortion. This is commonly illustrated by the impossibility of smoothing an orange peel onto a flat surface without tearing and deforming it. The only true representation of a sphere at constant scale is another sphere such as a [[globe]]. |

|||

Given the limited practical size of globes, we must use maps for detailed mapping. Maps require projections. A projection implies distortion: A constant separation on the map does not correspond to a constant separation on the ground. While a map may display a graphical bar scale, the scale must be used with the understanding that it will be accurate on only some lines of the map. (This is discussed further in the examples in the following sections.) |

|||

Let ''P'' be a point at latitude <math>\varphi</math> and longitude <math>\lambda</math> on the sphere (or [[ellipsoid]]). Let Q be a neighbouring point and let <math>\alpha</math> be the angle between the element PQ and the meridian at P: this angle is the '''azimuth''' angle of the element PQ. Let P' and Q' be corresponding points on the projection. The angle between the direction P'Q' and the projection of the meridian is the '''bearing''' <math>\beta</math>. In general <math>\alpha\ne\beta</math>. Comment: this precise distinction between azimuth (on the Earth's surface) and bearing (on the map) is not universally observed, many writers using the terms almost interchangeably. |

|||

'''Definition:''' the '''point scale''' at P is the ratio of the two distances P'Q' and PQ in the limit that Q approaches P. We write this as |

|||

::<math>\mu(\lambda,\,\varphi,\,\alpha)=\lim_{Q\to P}\frac{P'Q'}{PQ},</math> |

|||

where the notation indicates that the point scale is a function of the position of P and also the direction of the element PQ. |

|||

'''Definition:''' if P and Q lie on the same meridian <math>(\alpha=0)</math>, the '''meridian scale''' is denoted by <math>h(\lambda,\,\varphi)</math> . |

|||

'''Definition:''' if P and Q lie on the same parallel <math>(\alpha=\pi/2)</math>, the '''parallel scale''' is denoted by <math>k(\lambda,\,\varphi)</math>. |

|||

'''Definition:''' if the point scale depends only on position, not on direction, we say that it is [[Isotropy|isotropic]] and conventionally denote its value in any direction by the parallel scale factor <math>k(\lambda,\varphi)</math>. |

|||

'''Definition:''' A map projection is said to be [[Conformal map projection|conformal]] if the angle between a pair of lines intersecting at a point P is the same as the angle between the projected lines at the projected point P', for all pairs of lines intersecting at point P. A conformal map has an isotropic scale factor. Conversely isotropic scale factors across the map imply a conformal projection. |

|||

Isotropy of scale implies that ''small'' elements are stretched equally in all directions, that is the shape of a small element is preserved. This is the property of '''orthomorphism''' (from Greek 'right shape'). The qualification 'small' means that at some given accuracy of measurement no change can be detected in the scale factor over the element. Since conformal projections have an isotropic scale factor they have also been called '''orthomorphic projections'''. For example, the Mercator projection is conformal since it is constructed to preserve angles and its scale factor is isotropic, a function of latitude only: Mercator ''does'' preserve shape in small regions. |

|||

'''Definition:''' on a conformal projection with an isotropic scale, points which have the same scale value may be joined to form the '''isoscale lines'''. These are not plotted on maps for end users but they feature in many of the standard texts. (See Snyder<ref name=snyder/> pages 203—206.) |

|||

===Visualisation of point scale: the Tissot indicatrix=== |

|||

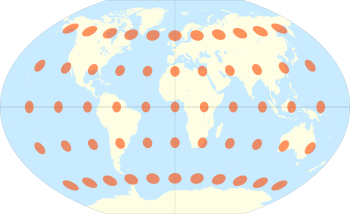

[[File:Tissot indicatrix world map Winkel Tripel proj.svg|thumb|right|350px|The Winkel tripel projection with [[Tissot's indicatrix]] of deformation]] |

|||

Consider a small circle on the surface of the Earth centred at a point P at latitude <math>\varphi</math> and longitude <math>\lambda</math>. Since the point scale varies with position and direction the projection of the circle on the projection will be distorted. [[Nicolas Auguste Tissot|Tissot]] proved that, as long as the distortion is not too great, the circle will become an ellipse on the projection. In general the dimension, shape and orientation of the ellipse will change over the projection. Superimposing these distortion ellipses on the map projection conveys the way in which the point scale is changing over the map. The distortion ellipse is known as [[Tissot's indicatrix]]. The example shown here is the [[Winkel tripel projection]], the standard projection for world maps made by the [[National Geographic Society]]. The minimum distortion is on the central meridian at latitudes of 30 degrees (North and South). (Other examples<ref>[http://www.progonos.com/furuti/MapProj/Normal/CartProp/Distort/distort.html Examples of Tissot's indicatrix.] Some illustrations of the Tissot Indicatrix applied to a variety of projections other than normal cylindrical.</ref><ref>[http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Map_projections_with_Tissot%27s_indicatrix Further examples of Tissot's indicatrix] at Wikimedia Commons.</ref>). |

|||

== Референце == |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== Литература == |

|||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* {{Cite web |url=http://www.cartography.org.uk/default.asp?contentID=749 |title=The British Cartographic Society > How long is the UK coastline? |access-date=2008-12-06 |archive-date=2012-05-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120522042745/http://www.cartography.org.uk/default.asp?contentID=749 |url-status=dead }} |

|||

* {{cite journal|title=Reference points and distance computations|journal=Code of Federal Regulations (Annual Edition). Title 47: Telecommunication.|date=October 1, 2016|volume=73|issue=208|url=https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2016-title47-vol4/pdf/CFR-2016-title47-vol4-sec73-208.pdf|access-date=8 November 2017}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

|last = Clairaut |

|||

|first = A. C. |

|||

|date = 1735 |

|||

|title = Détermination géometrique de la perpendiculaire à la méridienne tracée par M. Cassini |

|||

|trans-title = Geometrical determination of the perpendicular to the meridian drawn by Jacques Cassini |

|||

|language = fr |

|||

|journal = Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences de Paris 1733 |

|||

|pages = 406–416 |

|||

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=GOAEAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA406 |

|||

|author-link = Alexis Claude Clairaut }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

|last = Legendre |

|||

|first = A. M. |

|||

|date = 1806 |

|||

|title = Analyse des triangles tracées sur la surface d'un sphéroïde |

|||

|trans-title = Analysis of spheroidal triangles |

|||

|language = fr |

|||

|journal = Mémoires de l'Institut National de France |

|||

|number = 1st semester |

|||

|pages = 130–161 |

|||

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=EnVFAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA130 |

|||

|author-link = Adrien-Marie Legendre |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

| ref = {{harvid|Bessel|1825}} |

|||

| last1 = Bessel | first1 = F. W. |

|||

| author1-link = Friedrich Bessel |

|||

| date = 2010 |

|||

| doi = 10.1002/asna.201011352 |

|||

| title = The calculation of longitude and latitude from geodesic measurements |

|||

| journal = Astronomische Nachrichten |

|||

| volume = 331 | issue = 8 | pages = 852–861 |

|||

| arxiv = 0908.1824 |

|||

| orig-year = 1825 |

|||

| others = . Translated by C. F. F. Karney & R. E. Deakin |

|||

| postscript = . English translation of [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1825AN......4..241B ''Astron. Nachr.'' '''4''', 241–254 (1825)]. [https://geographiclib.sourceforge.io/bessel-errata.html Errata]. |

|||

| bibcode = 2010AN....331..852K |

|||

| s2cid = 118760590 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

|ref = {{harvid|Helmert|1880}} |

|||

|last = Helmert |

|||

|first = F. R. |

|||

|date = 1964 |

|||

|orig-year = 1880 |

|||

|title = Mathematical and Physical Theories of Higher Geodesy |

|||

|volume = 1 |

|||

|publisher = Aeronautical Chart and Information Center |

|||

|location = St. Louis |

|||

|url = https://geographiclib.sourceforge.io/geodesic-papers/helmert80-en.html |

|||

|author-link = Friedrich Robert Helmert |

|||

|postscript = . English translation of [https://books.google.com/books?id=qt2CAAAAIAAJ ''Die Mathematischen und Physikalischen Theorieen der Höheren Geodäsie''], Vol. 1 (Teubner, Leipzig, 1880). |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite techreport |

|||

|first=R. H. |last=Rapp |

|||

|title=Geometric Geodesy, Part II |

|||

|institution=Ohio State University |

|||

|date=March 1993 |

|||

|url=http://hdl.handle.net/1811/24409 |

|||

|access-date=2011-08-01 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

|first=T. |last=Vincenty |author-link=Thaddeus Vincenty |

|||

|title=Direct and Inverse Solutions of Geodesics on the Ellipsoid with application of nested equations |

|||

|journal=Survey Review |

|||

|volume=23 |issue=176 |date=April 1975 |pages=88–93 |

|||

|doi = 10.1179/sre.1975.23.176.88 |

|||

|url=http://www.ngs.noaa.gov/PUBS_LIB/inverse.pdf |access-date=2009-07-11 |

|||

|postscript = . Addendum: Survey Review '''23''' (180): 294 (1976). |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal | last1 = Karney | first1 = C. F. F. | doi = 10.1007/s00190-012-0578-z | title = Algorithms for geodesics | journal = Journal of Geodesy | volume = 87 | pages = 43–55| year = 2013| issue = 1| postscript = (open access). [https://geographiclib.sourceforge.io/geod-addenda.html Addenda].|arxiv = 1109.4448 |bibcode = 2013JGeod..87...43K | s2cid = 119310141 }} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

|url = https://geographiclib.sourceforge.io |

|||

|last = Karney |

|||

|first = C. F. F. |

|||

|title = GeographicLib |

|||

|version = 1.32 |

|||

|date = 2013 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite report |

|||

|last = Rapp |

|||

|first = R, H |

|||

|title = Geometric Geodesy, Part I |

|||

|date = 1991 |

|||

|publisher = Ohio Start Univ. |

|||

|hdl = 1811/24333 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

|last = Bowring |

|||

|first = B. R. |

|||

|title = The direct and inverse problems for short geodesics lines on the ellipsoid |

|||

|journal = Surveying and Mapping |

|||

|volume = 41 |

|||

|number = 2 |

|||

|date = 1981 |

|||

|pages = 135–141 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

|last = Lambert |

|||

|first = W. D |

|||

|title = The distance between two widely separated points on the surface of the earth |

|||

|journal = J. Washington Academy of Sciences |

|||

|date = 1942 |

|||

|volume = 32 |

|||

|number = 5 |

|||

|pages = 125–130 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.tech.mtu.edu/courses/su3150/Reference%20Material/Vincenty.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=2014-08-26 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140827072956/http://www.tech.mtu.edu/courses/su3150/Reference%20Material/Vincenty.pdf |archive-date=2014-08-27 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Ahl |first1=Valerie |last2=Allen |first2=Timothy F. H. |date=1996 |title=Hierarchy theory: a vision, vocabulary, and epistemology |location=New York |publisher=[[Columbia University Press]] |isbn=0231084803 |oclc=34149766 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZLR-G6I5wiQC }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Giampietro |first1=Mario |last2=Allen |first2=Timothy F. H. |last3=Mayumi |first3=Kozo |date=December 2006 |title=The epistemological predicament associated with purposive quantitative analysis |journal=[[Ecological Complexity]] |volume=3 |issue=4 |pages=307–327 |doi=10.1016/j.ecocom.2007.02.005 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228396570 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Kovacic |first1=Zora |last2=Giampietro |first2=Mario |date=December 2015 |title=Empty promises or promising futures? The case of smart grids |journal=[[Energy (journal)|Energy]] |volume=93 |issue=Part 1 |pages=67–74 |doi=10.1016/j.energy.2015.08.116 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281639433 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Serrano-Tovar |first1=Tarik |last2=Giampietro |first2=Mario |date=January 2014 |title=Multi-scale integrated analysis of rural Laos: studying metabolic patterns of land uses across different levels and scales |journal=Land Use Policy |volume=36 |pages=155–170 |doi=10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.08.003 }} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

Верзија на датум 11. фебруар 2023. у 11:36

Размера или размер је однос између дужине неке дужи представљене на цртежу (плану, карти) и њој одговарајуће дужине у природи која је на цртежу хоризонтално пројектована. Размера се обично представља количником 1:n, где број n означава колико пута је пута дужина у природи n смањена (или ређе, повећана). То је бројна размера, која се увек изражава у виду разломка, код кога је бројилац једнак јединици.

При упоређењу две размере (R1, R2) за једну се каже да је крупнија ако је њен број n1 мањи од броја n2 друге размере, и обратно, за другу размеру R2 каже се да је ситнија ако је n2 > n1. Избор размере зависи од: намене цртежа (плана), од условљене тачности тог цртежа; од врсте, величине и облика цртежа, као и од међусобног односа објеката које треба представити. Размера представљена у графичком облику назива се размерник.

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

If the region of the map is small enough to ignore Earth's curvature, such as in a town plan, then a single value can be used as the scale without causing measurement errors. In maps covering larger areas, or the whole Earth, the map's scale may be less useful or even useless in measuring distances. The map projection becomes critical in understanding how scale varies throughout the map.[1][2] When scale varies noticeably, it can be accounted for as the scale factor. Tissot's indicatrix is often used to illustrate the variation of point scale across a map.

Историја

The foundations for quantitative map scaling goes back to ancient China with textual evidence that the idea of map scaling was understood by the second century BC. Ancient Chinese surveyors and cartographers had ample technical resources used to produce maps such as counting rods, carpenter's square's, plumb lines, compasses for drawing circles, and sighting tubes for measuring inclination. Reference frames postulating a nascent coordinate system for identifying locations were hinted by ancient Chinese astronomers that divided the sky into various sectors or lunar lodges.[3]

The Chinese cartographer and geographer Pei Xiu of the Three Kingdoms period created a set of large-area maps that were drawn to scale. He produced a set of principles that stressed the importance of consistent scaling, directional measurements, and adjustments in land measurements in the terrain that was being mapped.[3]

Large-scale maps with curvature neglected

The region over which the earth can be regarded as flat depends on the accuracy of the survey measurements. If measured only to the nearest metre, then curvature of the earth is undetectable over a meridian distance of about 100 km (62 mi) and over an east-west line of about 80 km (at a latitude of 45 degrees). If surveyed to the nearest 1 mm (0,039 in), then curvature is undetectable over a meridian distance of about 10 km and over an east-west line of about 8 km.[4] Thus a plan of New York City accurate to one metre or a building site plan accurate to one millimetre would both satisfy the above conditions for the neglect of curvature. They can be treated by plane surveying and mapped by scale drawings in which any two points at the same distance on the drawing are at the same distance on the ground. True ground distances are calculated by measuring the distance on the map and then multiplying by the inverse of the scale fraction or, equivalently, simply using dividers to transfer the separation between the points on the map to a bar scale on the map.

Point scale (or particular scale)

As proved by Gauss’s Theorema Egregium, a sphere (or ellipsoid) cannot be projected onto a plane without distortion. This is commonly illustrated by the impossibility of smoothing an orange peel onto a flat surface without tearing and deforming it. The only true representation of a sphere at constant scale is another sphere such as a globe.

Given the limited practical size of globes, we must use maps for detailed mapping. Maps require projections. A projection implies distortion: A constant separation on the map does not correspond to a constant separation on the ground. While a map may display a graphical bar scale, the scale must be used with the understanding that it will be accurate on only some lines of the map. (This is discussed further in the examples in the following sections.)

Let P be a point at latitude and longitude on the sphere (or ellipsoid). Let Q be a neighbouring point and let be the angle between the element PQ and the meridian at P: this angle is the azimuth angle of the element PQ. Let P' and Q' be corresponding points on the projection. The angle between the direction P'Q' and the projection of the meridian is the bearing . In general . Comment: this precise distinction between azimuth (on the Earth's surface) and bearing (on the map) is not universally observed, many writers using the terms almost interchangeably.

Definition: the point scale at P is the ratio of the two distances P'Q' and PQ in the limit that Q approaches P. We write this as

where the notation indicates that the point scale is a function of the position of P and also the direction of the element PQ.

Definition: if P and Q lie on the same meridian , the meridian scale is denoted by .

Definition: if P and Q lie on the same parallel , the parallel scale is denoted by .

Definition: if the point scale depends only on position, not on direction, we say that it is isotropic and conventionally denote its value in any direction by the parallel scale factor .

Definition: A map projection is said to be conformal if the angle between a pair of lines intersecting at a point P is the same as the angle between the projected lines at the projected point P', for all pairs of lines intersecting at point P. A conformal map has an isotropic scale factor. Conversely isotropic scale factors across the map imply a conformal projection.

Isotropy of scale implies that small elements are stretched equally in all directions, that is the shape of a small element is preserved. This is the property of orthomorphism (from Greek 'right shape'). The qualification 'small' means that at some given accuracy of measurement no change can be detected in the scale factor over the element. Since conformal projections have an isotropic scale factor they have also been called orthomorphic projections. For example, the Mercator projection is conformal since it is constructed to preserve angles and its scale factor is isotropic, a function of latitude only: Mercator does preserve shape in small regions.

Definition: on a conformal projection with an isotropic scale, points which have the same scale value may be joined to form the isoscale lines. These are not plotted on maps for end users but they feature in many of the standard texts. (See Snyder[1] pages 203—206.)

Visualisation of point scale: the Tissot indicatrix

Consider a small circle on the surface of the Earth centred at a point P at latitude and longitude . Since the point scale varies with position and direction the projection of the circle on the projection will be distorted. Tissot proved that, as long as the distortion is not too great, the circle will become an ellipse on the projection. In general the dimension, shape and orientation of the ellipse will change over the projection. Superimposing these distortion ellipses on the map projection conveys the way in which the point scale is changing over the map. The distortion ellipse is known as Tissot's indicatrix. The example shown here is the Winkel tripel projection, the standard projection for world maps made by the National Geographic Society. The minimum distortion is on the central meridian at latitudes of 30 degrees (North and South). (Other examples[5][6]).

Референце

- ^ а б Snyder, John P. (1987). Map Projections - A Working Manual. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1395. United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.This paper can be downloaded from USGS pages. It gives full details of most projections, together with introductory sections, but it does not derive any of the projections from first principles. Derivation of all the formulae for the Mercator projections may be found in The Mercator Projections.

- ^ Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections, John P. Snyder, 1993, pp. 5-8, ISBN 0-226-76747-7. This is a survey of virtually all known projections from antiquity to 1993.

- ^ а б Selin, Helaine (2008). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer (објављено 17. 3. 2008). стр. 567. ISBN 978-1402049606.

- ^ Osborne, Peter (2013), The Mercator Projections, doi:10.5281/zenodo.35392. (Supplements: Maxima files and Latex code and figures)

- ^ Examples of Tissot's indicatrix. Some illustrations of the Tissot Indicatrix applied to a variety of projections other than normal cylindrical.

- ^ Further examples of Tissot's indicatrix at Wikimedia Commons.

Литература

- „The British Cartographic Society > How long is the UK coastline?”. Архивирано из оригинала 2012-05-22. г. Приступљено 2008-12-06.

- „Reference points and distance computations” (PDF). Code of Federal Regulations (Annual Edition). Title 47: Telecommunication. 73 (208). 1. 10. 2016. Приступљено 8. 11. 2017.

- Clairaut, A. C. (1735). „Détermination géometrique de la perpendiculaire à la méridienne tracée par M. Cassini” [Geometrical determination of the perpendicular to the meridian drawn by Jacques Cassini]. Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences de Paris 1733 (на језику: француски): 406–416.

- Legendre, A. M. (1806). „Analyse des triangles tracées sur la surface d'un sphéroïde” [Analysis of spheroidal triangles]. Mémoires de l'Institut National de France (на језику: француски) (1st semester): 130–161.

- Bessel, F. W. (2010) [1825]. . Translated by C. F. F. Karney & R. E. Deakin. „The calculation of longitude and latitude from geodesic measurements”. Astronomische Nachrichten. 331 (8): 852–861. Bibcode:2010AN....331..852K. S2CID 118760590. arXiv:0908.1824

. doi:10.1002/asna.201011352. English translation of Astron. Nachr. 4, 241–254 (1825). Errata.

. doi:10.1002/asna.201011352. English translation of Astron. Nachr. 4, 241–254 (1825). Errata. - Helmert, F. R. (1964) [1880]. Mathematical and Physical Theories of Higher Geodesy. 1. St. Louis: Aeronautical Chart and Information Center. English translation of Die Mathematischen und Physikalischen Theorieen der Höheren Geodäsie, Vol. 1 (Teubner, Leipzig, 1880).

- Rapp, R. H. (март 1993). Geometric Geodesy, Part II (Технички извештај). Ohio State University. Приступљено 2011-08-01.

- Vincenty, T. (април 1975). „Direct and Inverse Solutions of Geodesics on the Ellipsoid with application of nested equations” (PDF). Survey Review. 23 (176): 88–93. doi:10.1179/sre.1975.23.176.88. Приступљено 2009-07-11. Addendum: Survey Review 23 (180): 294 (1976).

- Karney, C. F. F. (2013). „Algorithms for geodesics”. Journal of Geodesy. 87 (1): 43—55. Bibcode:2013JGeod..87...43K. S2CID 119310141. arXiv:1109.4448

. doi:10.1007/s00190-012-0578-z(open access). Addenda.

. doi:10.1007/s00190-012-0578-z(open access). Addenda. - Karney, C. F. F. (2013). „GeographicLib”. 1.32.

- Rapp, R, H (1991). Geometric Geodesy, Part I (Извештај). Ohio Start Univ. hdl:1811/24333.

- Bowring, B. R. (1981). „The direct and inverse problems for short geodesics lines on the ellipsoid”. Surveying and Mapping. 41 (2): 135–141.

- Lambert, W. D (1942). „The distance between two widely separated points on the surface of the earth”. J. Washington Academy of Sciences. 32 (5): 125–130.

- „Archived copy” (PDF). Архивирано из оригинала (PDF) 2014-08-27. г. Приступљено 2014-08-26.

- Ahl, Valerie; Allen, Timothy F. H. (1996). Hierarchy theory: a vision, vocabulary, and epistemology. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231084803. OCLC 34149766.

- Giampietro, Mario; Allen, Timothy F. H.; Mayumi, Kozo (децембар 2006). „The epistemological predicament associated with purposive quantitative analysis”. Ecological Complexity. 3 (4): 307—327. doi:10.1016/j.ecocom.2007.02.005.

- Kovacic, Zora; Giampietro, Mario (децембар 2015). „Empty promises or promising futures? The case of smart grids”. Energy. 93 (Part 1): 67—74. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.08.116.

- Serrano-Tovar, Tarik; Giampietro, Mario (јануар 2014). „Multi-scale integrated analysis of rural Laos: studying metabolic patterns of land uses across different levels and scales”. Land Use Policy. 36: 155—170. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.08.003.