Vidljivi spektar — разлика између измена

ознака: промењено одредиште преусмерења |

. ознака: уклоњено преусмерење |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{short description|Deo elektromagnetnog spektra koji je vidljiv ljudskom oku}} |

|||

#Преусмери [[Светлост]] |

|||

[[File:Light dispersion of a mercury-vapor lamp with a flint glass prism IPNr°0125.jpg|thumb|Bela [[svetlost]] se [[Дисперзија (физика)|disperguje]] [[Dispersive prism|prizmom]] u boje vidljivog spektra.]] |

|||

'''Vidljivi spektar''' je porcija [[electromagnetic spectrum|elektromagnetnog spektra]] koja je [[visual perception|vidljiva]] [[human eye|ljudskim okom]]. [[Electromagnetic radiation|Elektromagnetan radijacija]] u ovom opsegu [[wavelength|talasnih dužina]] se naziva '''vidljiva svetlost''' ili jednostavno [[svetlost]]. Tipično [[human eye|ljudsko oko]] reaguje na talasne dužine od oko 380 do 740 [[nanometar]]a.<ref>{{cite book | title = Biology: Concepts and Applications | author = Starr, Cecie | publisher = Thomson Brooks/Cole | year = 2005 | isbn = 978-0-534-46226-0 | url = https://books.google.com/?id=RtSpGV_Pl_0C&pg=PA94}}</ref> Po frekvenciji, to odgovara opsegu u blizini 430–770 [[Hertz#SI prefixed forms of hertz|-{THz}-]]. |

|||

{{rut}} |

|||

The spectrum does not contain all the [[color]]s that the human eyes and brain can distinguish. [[Excitation purity|Unsaturated colors]] such as [[pink]], or [[purple]] variations like [[magenta]], for example, are absent because they can only be made from a mix of multiple wavelengths. Colors containing only one wavelength are also called [[Excitation purity|pure colors]] or spectral colors. |

|||

Visible wavelengths pass largely unattenuated through the [[Earth's atmosphere]] via the "[[optical window]]" region of the electromagnetic spectrum. An example of this phenomenon is when clean air [[scattering|scatters]] blue light more than red light, and so the midday sky appears blue. The optical window is also referred to as the "visible window" because it overlaps the human visible response spectrum. The [[near infrared]] (NIR) window lies just out of the human vision, as well as the medium wavelength infrared (MWIR) window, and the long wavelength or far infrared (LWIR or FIR) window, although other animals may experience them. |

|||

== Istorija == |

|||

[[File:Newton's color circle.png|thumb|Newton's color circle, from ''Opticks'' of 1704, showing the colors he associated with [[musical note]]s. The spectral colors from red to violet are divided by the notes of the musical scale, starting at D. The circle completes a full [[octave]], from D to D. Newton's circle places red, at one end of the spectrum, next to violet, at the other. This reflects the fact that non-spectral [[purple]] colors are observed when red and violet light are mixed.]] |

|||

In the 13th century, [[Roger Bacon]] theorized that [[rainbow]]s were produced by a similar process to the passage of light through glass or crystal.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=j8BCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA185&dq=%22roger+bacon%22+prism|title=The Science of Logic: An Inquiry Into the Principles of Accurate Thought |first=Peter|last=Coffey|year=1912|publisher=Longmans}}</ref> |

|||

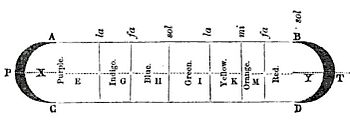

In the 17th century, [[Isaac Newton]] discovered that prisms could disassemble and reassemble white light, and described the phenomenon in his book ''[[Opticks]]''. He was the first to use the word ''spectrum'' ([[Latin]] for "appearance" or "apparition") in this sense in print in 1671 in describing his [[experiment]]s in [[optics]]. Newton observed that, when a narrow beam of [[sunlight]] strikes the face of a glass [[Dispersive prism|prism]] at an angle, some is [[Reflection (physics)|reflected]] and some of the beam passes into and through the glass, emerging as different-colored bands. Newton hypothesized light to be made up of "corpuscles" (particles) of different colors, with the different colors of light moving at different speeds in transparent matter, red light moving more quickly than violet in glass. The result is that red light is bent ([[refraction|refracted]]) less sharply than violet as it passes through the prism, creating a spectrum of colors. |

|||

[[File:Newton prismatic colours.JPG|thumb|left|350px|Newton's observation of prismatic colors ([[David Brewster]] 1855)]] Newton originally divided the spectrum into six named colors: [[red]], [[Orange (color)|orange]], [[yellow]], [[green]], [[blue]], and [[Violet (color)|violet]]. He later added [[indigo]] as the seventh color since he believed that seven was a perfect number as derived from the [[Ancient Greece|ancient Greek]] [[Sophism|sophists]], of there being a connection between the colors, the musical notes, the known objects in the [[solar system]], and the days of the week.<ref name="Isacoff2009">{{cite book|last=Isacoff|first=Stuart|title=Temperament: How Music Became a Battleground for the Great Minds of Western Civilization|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2kasFeTRcf4C&pg=PA12|accessdate=18 March 2014|date=16 January 2009|publisher=Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-307-56051-3|pages=12–13}}</ref> The human eye is relatively insensitive to indigo's frequencies, and some people who have otherwise-good vision cannot distinguish indigo from blue and violet. For this reason, some later commentators, including [[Isaac Asimov]],<ref>{{cite book|last=Asimov|first=Isaac|title=Eyes on the universe : a history of the telescope|year=1975|publisher=Houghton Mifflin|location=Boston|isbn=978-0-395-20716-1|page=59}}</ref> have suggested that indigo should not be regarded as a color in its own right but merely as a shade of blue or violet. Evidence indicates that what Newton meant by "indigo" and "blue" does not correspond to the modern meanings of those color words. Comparing Newton's observation of prismatic colors to a color image of the visible light spectrum shows that "indigo" corresponds to what is today called blue, whereas "blue" corresponds to [[cyan]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Evans|first=Ralph M.|title=The perception of color|year=1974|publisher=Wiley-Interscience|location=New York|isbn=978-0-471-24785-2|edition=null}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=McLaren|first=K.|title=Newton's indigo|journal=Color Research & Application|date=March 2007|volume=10|issue=4|pages=225–229|doi=10.1002/col.5080100411}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Waldman|first=Gary|title=Introduction to light : the physics of light, vision, and color|year=2002|publisher=Dover Publications|location=Mineola|isbn=978-0-486-42118-6|pages=193|url=https://books.google.com/?id=PbsoAXWbnr4C&pg=PA193&dq=Newton+color+Indigo#v=onepage&q=Newton%20color%20Indigo&f=false|edition=Dover}}</ref> |

|||

In the 18th century, [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe]] wrote about optical spectra in his ''[[Theory of Colours (book)|Theory of Colours]]''. Goethe used the word ''spectrum'' (''Spektrum'') to designate a ghostly optical [[afterimage]], as did [[Arthur Schopenhauer|Schopenhauer]] in ''[[On Vision and Colors]]''. Goethe argued that the continuous spectrum was a compound phenomenon. Where Newton narrowed the beam of light to isolate the phenomenon, Goethe observed that a wider aperture produces not a spectrum but rather reddish-yellow and blue-cyan edges with [[white]] between them. The spectrum appears only when these edges are close enough to overlap. |

|||

In the early 19th century, the concept of the visible spectrum became more definite, as light outside the visible range was discovered and characterized by [[William Herschel]] ([[infrared]]) and [[Johann Wilhelm Ritter]] ([[ultraviolet]]), [[Thomas Young (scientist)|Thomas Young]], [[Thomas Johann Seebeck]], and others.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| title = The Cambridge History of Science: The Modern Physical and Mathematical Sciences |

|||

| volume = 5 |

|||

| editor = Mary Jo Nye |

|||

| publisher = Cambridge University Press |

|||

| year = 2003 |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-521-57199-9 |

|||

| page = 278 |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/?id=B3WvWhJTTX8C&pg=PA278&dq=spectrum+%22thomas+young%22+herschel+ritter |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Young was the first to measure the wavelengths of different colors of light, in 1802.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| title = Lines of light: the sources of dispersive spectroscopy, 1800–1930 |

|||

| author = John C. D. Brand |

|||

| publisher = CRC Press |

|||

| year = 1995 |

|||

| isbn = 978-2-88449-163-1 |

|||

| pages = 30–32 |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/?id=sKx0IBC22p4C&pg=PA30&dq=light+wavelength+color++young+fresnel |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

The connection between the visible spectrum and [[color vision]] was explored by Thomas Young and [[Hermann von Helmholtz]] in the early 19th century. Their [[Young–Helmholtz theory|theory of color vision]] correctly proposed that the eye uses three distinct receptors to perceive color. |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

== Percepcija boja kod raznih vrsta == |

|||

{{See also-lat|Color vision#Physiology of color perception}} |

|||

Many species can see light within frequencies outside the human "visible spectrum". [[Bee]]s and many other insects can detect ultraviolet light, which helps them find [[nectar (plant)|nectar]] in flowers. Plant species that depend on insect pollination may owe reproductive success to their appearance in ultraviolet light rather than how colorful they appear to humans. Birds, too, can see into the ultraviolet (300–400 nm), and some have sex-dependent markings on their plumage that are visible only in the ultraviolet range.<ref>{{cite book|last=Cuthill|first=Innes C |authorlink=Innes Cuthill |editor=Peter J.B. Slater|title=Advances in the Study of Behavior|publisher=Academic Press|location=Oxford, England|year=1997|volume=29|chapter=Ultraviolet vision in birds|page=161|isbn=978-0-12-004529-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Jamieson|first=Barrie G. M. |title=Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Birds|publisher=University of Virginia|location=Charlottesville VA|year=2007|page=128|isbn=978-1-57808-386-2}}</ref> Many animals that can see into the ultraviolet range cannot see red light or any other reddish wavelengths. Bees' visible spectrum ends at about 590 nm, just before the orange wavelengths start.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Skorupski|first=Peter|last2=Chittka|first2=Lars|date=10 August 2010 |title=Photoreceptor Spectral Sensitivity in the Bumblebee, ''Bombus impatiens'' (Hymenoptera: Apidae) |journal=PLoS ONE |volume=5 |issue=8 |pages=e12049 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0012049 |pmid=20711523|pmc=2919406|bibcode = 2010PLoSO...512049S }}</ref> Birds can see some red wavelengths, although not as far into the light spectrum as humans.<ref name="Varela">Varela, F. J.; Palacios, A. G.; Goldsmith T. M. (1993) [https://books.google.com/books/about/Vision_Brain_and_Behavior_in_Birds.html?id=p1SUzc5GUVcC&redir_esc=y "Color vision of birds"], pp. 77–94 in ''Vision, Brain, and Behavior in Birds'', eds. Zeigler, Harris Philip and Bischof, Hans-Joachim. MIT Press. {{ISBN|9780262240369}}</ref> The popular belief that the common goldfish is the only animal that can see both infrared and ultraviolet light<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.skeptive.com/disputes/4484 |title=True or False? "The common goldfish is the only animal that can see both infra-red and ultra-violet light." |work= Skeptive |date=2013|accessdate=September 28, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131224110616/http://www.skeptive.com/disputes/4484 |archive-date=December 24, 2013 |dead-url=yes |df=mdy-all }}</ref> is incorrect, because goldfish cannot see infrared light.<ref>{{cite book |last=Neumeyer |first=Christa |editor1-first=Olga |editor1-last=Lazareva |editor2-first=Toru |editor2-last=Shimizu |editor3-first=Edward |editor3-last=Wasserman |title= How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision |publisher=Oxford Scholarship Online |year=2012 |chapter=Chapter 2: Color Vision in Goldfish and Other Vertebrates |isbn= 978-0-19-533465-4}}</ref> Similarly, dogs are often thought to be color blind but they have been shown to be sensitive to colors, though not as many as humans.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1098/rspb.2013.1356 |pmid= 23864600|pmc= 3730601|title= Colour cues proved to be more informative for dogs than brightness|journal= Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences|volume= 280|issue= 1766|pages= 20131356|year= 2013|last1= Kasparson|first1= A. A|last2= Badridze|first2= J|last3= Maximov|first3= V. V}}</ref> Some snakes can "see"<ref>{{cite journal | pmc = 2693128 | pmid=7256281 | volume=213 | issue=4509 | title=Integration of visual and infrared information in bimodal neurons in the rattlesnake optic tectum | year=1981 | journal=Science | pages=789–91 | last1 = Newman | first1 = EA | last2 = Hartline | first2 = PH | doi=10.1126/science.7256281| bibcode=1981Sci...213..789N }}</ref> radiant heat at [[wavelength]]s between 5 and 30 [[Micrometre|μm]] to a degree of accuracy such that a blind [[rattlesnake]] can target vulnerable body parts of the prey at which it strikes,<ref name="KM">{{cite journal | last1 = Kardong | first1 = KV | last2 = Mackessy | first2 = SP | year = 1991 | title = The strike behavior of a congenitally blind rattlesnake | url = | journal = Journal of Herpetology | volume = 25 | issue = 2| pages = 208–211 | doi=10.2307/1564650| jstor = 1564650 }}</ref> and other snakes with the organ may detect warm bodies from a meter away.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1038/news.2010.122 |title=Snake infrared detection unravelled |author=Fang, Janet |journal=Nature News|date=14 March 2010 }}</ref> It may also be used in [[thermoregulation]] and [[predator]] detection.<ref name="KBLaD">{{cite journal|last=Krochmal|first=Aaron R.|author2=George S. Bakken |author3=Travis J. LaDuc |title=Heat in evolution's kitchen: evolutionary perspectives on the functions and origin of the facial pit of pitvipers (Viperidae: Crotalinae)|journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |date=15 November 2004|volume=207|pages=4231–4238|doi=10.1242/jeb.01278|pmid=15531644|issue=Pt 24}}</ref><ref name="Gre92">Greene HW. (1992). "The ecological and behavioral context for pitviper evolution", in Campbell JA, Brodie ED Jr. ''Biology of the Pitvipers''. Texas: Selva. {{ISBN|0-9630537-0-1}}.</ref> (See [[Infrared sensing in snakes]]) |

|||

== Spektar boja == |

|||

{{Glavni-lat|Disperzija (optika)}} |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; width:400px; text-align:center; margin:0.5em auto; width:auto; margin-left:1em;" |

|||

! colspan="4" style="background:#FFF;" | [[File:Linear visible spectrum.svg|center|250px|sRGB rendering of the spectrum of visible light]] |

|||

|- |

|||

![[Boja]] |

|||

![[Talasna dužina]] |

|||

![[Frekvencija]] |

|||

![[Photon energy|Energija fotona]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="background:#ccb0f4;"|'''[[Violet (color)|Ljubičata]]''' |

|||

|380–450 nm |

|||

|680–790 THz |

|||

|2.95–3.10 [[Electronvolt|eV]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="background:#b0b0f4;"|'''[[Plava]]''' |

|||

|450–485 nm |

|||

|620–680 THz |

|||

|2.64–2.75 eV |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="background:#b0f4f4;"|'''[[Cijan]]''' |

|||

|485–500 nm |

|||

|600–620 THz |

|||

|2.48–2.52 eV |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="background:#b0f4b0;"|'''[[Zelena]]''' |

|||

|500–565 nm |

|||

|530–600 THz |

|||

|2.25–2.34 eV |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="background:#f4f4b0;"|'''[[Žuta]]''' |

|||

|565–590 nm |

|||

|510–530 THz |

|||

|2.10–2.17 eV |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="background:#f4ccb0;"|'''[[Orange (color)|Narandžasta]]''' |

|||

|590–625 nm |

|||

|480–510 THz |

|||

|2.00–2.10 eV |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="background:#f4b0b0;"|'''[[Crvena]]''' |

|||

|625–740 nm |

|||

|405–480 THz |

|||

|1.65–2.00 eV |

|||

|} |

|||

Colors that can be produced by visible light of a narrow band of wavelengths (monochromatic light) are called [[Spectral color|pure spectral colors]]. The various color ranges indicated in the illustration are an approximation: The spectrum is continuous, with no clear boundaries between one color and the next.<ref>Bruno, Thomas J. and Svoronos, Paris D. N. (2005). ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=FgjHjhCh5wsC&pg=PP1 CRC Handbook of Fundamental Spectroscopic Correlation Charts.]'' CRC Press. {{ISBN|9781420037685}}</ref> |

|||

Ako se uzak snop bele [[svetlost]]i propusti kroz pukotinu i da zatim prođe kroz [[Сочиво (оптика)|optičko sočivo]] tako da zraci u paralelnom snopu padaju na [[optička prizma|optičku prizmu]] dolazi do njegovog razlaganja. Pri tom prizma mora biti nameštena na minimum [[Devijacija|devijacije]]. Nakon [[Refrakcija|loma u prizmi]] taj će se uski snop svetlosti raširiti u široku prugu raznobojne svetlosti koja se zove spektar boja. Spektar bele svetlosti sastoji se od 6 boja i to: crvene, narančaste, žute, zelene, plave i ljubičaste koje neprekidno prelaze jedna u drugu. Ovo rastavljanje bele svetlosti u 6 spektralnih boja zove se [[Дисперзија (физика)|disperzija svetlosti]]. Disperziju svetlosti je prvi istražio [[Isaac Newton|I. Njutn]] i time objasnio hipotezu da je bela svetlost sastavljena iz različitih, takozvanih spektralnih boja. |

|||

Kako se prizmom svetlost dvaput lomi, to do disperzije dolazi zato što svaka spektralna boja ima različiti [[indeks loma]]. Kod toga se najmanje lomi crvena, a najviše ljubičasta svetlost. Dakle, indeks loma ljubičaste svetlosti veći je od indeksa loma crvene svetlosti. Odatle izlazi da se crvena i ljubičasta svetlost šire u [[staklo|staklu]] različitim [[brzina]]ma. Znači da [[brzina svetlosti]] u prozirnim sredstvima zavisi od boje svetlosti. Brzina crvene svetlosti je najveća. Sve manju brzinu ima po redu, narančasta, žuta, zelena, plava i modra svetlost, najmanju ljubičasta. |

|||

Merenja su pokazala da u [[vakuum]]u brzina svetlosti ne zavisi od njene boje. Stoga u vakuumu nema disperzije svetlosti. |

|||

Da je spektralna svetlost homogena i jednobojna ([[Monohromator|monohromatska]]), to jest da se ne može rastaviti, može se potvrditi [[eksperiment]]om. U zastoru na koji pada spektar boja napravi se uska pukotina tako da kroz nju prolazi snop jednobojne svetlosti i da pada na drugu prizmu. Druga prizma mora biti tako postavljena da joj lomni brid bude paralelan s lomnim bridom prve prizme. Zbog loma na prizmi svetlost će biti otklonjena, ali neće nastati disperzija.<ref> Velimir Kruz: "Tehnička fizika za tehničke škole", "Školska knjiga" Zagreb, 1969.</ref> |

|||

== Vidi još == |

|||

*[[High-energy visible light|Visokoenergetska vidljiva svetlost]] |

|||

*[[Electromagnetic absorption by water#Visible region|Elektromagnetna apsorpcija vodom]] |

|||

== Reference == |

|||

{{reflist|35em}} |

|||

== Spoljašnje veze == |

|||

{{Commons category-lat|Visible spectrum}} |

|||

{{Spektar-lat}} |

|||

{{Authority control-lat}} |

|||

[[Категорија:Боје]] |

|||

[[Категорија:Електромагнетни спектар]] |

|||

[[Категорија:Вид]] |

|||

Верзија на датум 8. август 2019. у 00:41

Vidljivi spektar je porcija elektromagnetnog spektra koja je vidljiva ljudskim okom. Elektromagnetan radijacija u ovom opsegu talasnih dužina se naziva vidljiva svetlost ili jednostavno svetlost. Tipično ljudsko oko reaguje na talasne dužine od oko 380 do 740 nanometara.[1] Po frekvenciji, to odgovara opsegu u blizini 430–770 THz.

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

The spectrum does not contain all the colors that the human eyes and brain can distinguish. Unsaturated colors such as pink, or purple variations like magenta, for example, are absent because they can only be made from a mix of multiple wavelengths. Colors containing only one wavelength are also called pure colors or spectral colors.

Visible wavelengths pass largely unattenuated through the Earth's atmosphere via the "optical window" region of the electromagnetic spectrum. An example of this phenomenon is when clean air scatters blue light more than red light, and so the midday sky appears blue. The optical window is also referred to as the "visible window" because it overlaps the human visible response spectrum. The near infrared (NIR) window lies just out of the human vision, as well as the medium wavelength infrared (MWIR) window, and the long wavelength or far infrared (LWIR or FIR) window, although other animals may experience them.

Istorija

In the 13th century, Roger Bacon theorized that rainbows were produced by a similar process to the passage of light through glass or crystal.[2]

In the 17th century, Isaac Newton discovered that prisms could disassemble and reassemble white light, and described the phenomenon in his book Opticks. He was the first to use the word spectrum (Latin for "appearance" or "apparition") in this sense in print in 1671 in describing his experiments in optics. Newton observed that, when a narrow beam of sunlight strikes the face of a glass prism at an angle, some is reflected and some of the beam passes into and through the glass, emerging as different-colored bands. Newton hypothesized light to be made up of "corpuscles" (particles) of different colors, with the different colors of light moving at different speeds in transparent matter, red light moving more quickly than violet in glass. The result is that red light is bent (refracted) less sharply than violet as it passes through the prism, creating a spectrum of colors.

Newton originally divided the spectrum into six named colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. He later added indigo as the seventh color since he believed that seven was a perfect number as derived from the ancient Greek sophists, of there being a connection between the colors, the musical notes, the known objects in the solar system, and the days of the week.[3] The human eye is relatively insensitive to indigo's frequencies, and some people who have otherwise-good vision cannot distinguish indigo from blue and violet. For this reason, some later commentators, including Isaac Asimov,[4] have suggested that indigo should not be regarded as a color in its own right but merely as a shade of blue or violet. Evidence indicates that what Newton meant by "indigo" and "blue" does not correspond to the modern meanings of those color words. Comparing Newton's observation of prismatic colors to a color image of the visible light spectrum shows that "indigo" corresponds to what is today called blue, whereas "blue" corresponds to cyan.[5][6][7]

In the 18th century, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote about optical spectra in his Theory of Colours. Goethe used the word spectrum (Spektrum) to designate a ghostly optical afterimage, as did Schopenhauer in On Vision and Colors. Goethe argued that the continuous spectrum was a compound phenomenon. Where Newton narrowed the beam of light to isolate the phenomenon, Goethe observed that a wider aperture produces not a spectrum but rather reddish-yellow and blue-cyan edges with white between them. The spectrum appears only when these edges are close enough to overlap.

In the early 19th century, the concept of the visible spectrum became more definite, as light outside the visible range was discovered and characterized by William Herschel (infrared) and Johann Wilhelm Ritter (ultraviolet), Thomas Young, Thomas Johann Seebeck, and others.[8] Young was the first to measure the wavelengths of different colors of light, in 1802.[9]

The connection between the visible spectrum and color vision was explored by Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz in the early 19th century. Their theory of color vision correctly proposed that the eye uses three distinct receptors to perceive color.

Percepcija boja kod raznih vrsta

Many species can see light within frequencies outside the human "visible spectrum". Bees and many other insects can detect ultraviolet light, which helps them find nectar in flowers. Plant species that depend on insect pollination may owe reproductive success to their appearance in ultraviolet light rather than how colorful they appear to humans. Birds, too, can see into the ultraviolet (300–400 nm), and some have sex-dependent markings on their plumage that are visible only in the ultraviolet range.[10][11] Many animals that can see into the ultraviolet range cannot see red light or any other reddish wavelengths. Bees' visible spectrum ends at about 590 nm, just before the orange wavelengths start.[12] Birds can see some red wavelengths, although not as far into the light spectrum as humans.[13] The popular belief that the common goldfish is the only animal that can see both infrared and ultraviolet light[14] is incorrect, because goldfish cannot see infrared light.[15] Similarly, dogs are often thought to be color blind but they have been shown to be sensitive to colors, though not as many as humans.[16] Some snakes can "see"[17] radiant heat at wavelengths between 5 and 30 μm to a degree of accuracy such that a blind rattlesnake can target vulnerable body parts of the prey at which it strikes,[18] and other snakes with the organ may detect warm bodies from a meter away.[19] It may also be used in thermoregulation and predator detection.[20][21] (See Infrared sensing in snakes)

Spektar boja

| Boja | Talasna dužina | Frekvencija | Energija fotona |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ljubičata | 380–450 nm | 680–790 THz | 2.95–3.10 eV |

| Plava | 450–485 nm | 620–680 THz | 2.64–2.75 eV |

| Cijan | 485–500 nm | 600–620 THz | 2.48–2.52 eV |

| Zelena | 500–565 nm | 530–600 THz | 2.25–2.34 eV |

| Žuta | 565–590 nm | 510–530 THz | 2.10–2.17 eV |

| Narandžasta | 590–625 nm | 480–510 THz | 2.00–2.10 eV |

| Crvena | 625–740 nm | 405–480 THz | 1.65–2.00 eV |

Colors that can be produced by visible light of a narrow band of wavelengths (monochromatic light) are called pure spectral colors. The various color ranges indicated in the illustration are an approximation: The spectrum is continuous, with no clear boundaries between one color and the next.[22]

Ako se uzak snop bele svetlosti propusti kroz pukotinu i da zatim prođe kroz optičko sočivo tako da zraci u paralelnom snopu padaju na optičku prizmu dolazi do njegovog razlaganja. Pri tom prizma mora biti nameštena na minimum devijacije. Nakon loma u prizmi taj će se uski snop svetlosti raširiti u široku prugu raznobojne svetlosti koja se zove spektar boja. Spektar bele svetlosti sastoji se od 6 boja i to: crvene, narančaste, žute, zelene, plave i ljubičaste koje neprekidno prelaze jedna u drugu. Ovo rastavljanje bele svetlosti u 6 spektralnih boja zove se disperzija svetlosti. Disperziju svetlosti je prvi istražio I. Njutn i time objasnio hipotezu da je bela svetlost sastavljena iz različitih, takozvanih spektralnih boja.

Kako se prizmom svetlost dvaput lomi, to do disperzije dolazi zato što svaka spektralna boja ima različiti indeks loma. Kod toga se najmanje lomi crvena, a najviše ljubičasta svetlost. Dakle, indeks loma ljubičaste svetlosti veći je od indeksa loma crvene svetlosti. Odatle izlazi da se crvena i ljubičasta svetlost šire u staklu različitim brzinama. Znači da brzina svetlosti u prozirnim sredstvima zavisi od boje svetlosti. Brzina crvene svetlosti je najveća. Sve manju brzinu ima po redu, narančasta, žuta, zelena, plava i modra svetlost, najmanju ljubičasta.

Merenja su pokazala da u vakuumu brzina svetlosti ne zavisi od njene boje. Stoga u vakuumu nema disperzije svetlosti.

Da je spektralna svetlost homogena i jednobojna (monohromatska), to jest da se ne može rastaviti, može se potvrditi eksperimentom. U zastoru na koji pada spektar boja napravi se uska pukotina tako da kroz nju prolazi snop jednobojne svetlosti i da pada na drugu prizmu. Druga prizma mora biti tako postavljena da joj lomni brid bude paralelan s lomnim bridom prve prizme. Zbog loma na prizmi svetlost će biti otklonjena, ali neće nastati disperzija.[23]

Vidi još

Reference

- ^ Starr, Cecie (2005). Biology: Concepts and Applications. Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-534-46226-0.

- ^ Coffey, Peter (1912). The Science of Logic: An Inquiry Into the Principles of Accurate Thought. Longmans.

- ^ Isacoff, Stuart (16. 1. 2009). Temperament: How Music Became a Battleground for the Great Minds of Western Civilization. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. стр. 12—13. ISBN 978-0-307-56051-3. Приступљено 18. 3. 2014.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1975). Eyes on the universe : a history of the telescope. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. стр. 59. ISBN 978-0-395-20716-1.

- ^ Evans, Ralph M. (1974). The perception of color (null изд.). New York: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-24785-2.

- ^ McLaren, K. (март 2007). „Newton's indigo”. Color Research & Application. 10 (4): 225—229. doi:10.1002/col.5080100411.

- ^ Waldman, Gary (2002). Introduction to light : the physics of light, vision, and color (Dover изд.). Mineola: Dover Publications. стр. 193. ISBN 978-0-486-42118-6.

- ^ Mary Jo Nye, ур. (2003). The Cambridge History of Science: The Modern Physical and Mathematical Sciences. 5. Cambridge University Press. стр. 278. ISBN 978-0-521-57199-9.

- ^ John C. D. Brand (1995). Lines of light: the sources of dispersive spectroscopy, 1800–1930. CRC Press. стр. 30—32. ISBN 978-2-88449-163-1.

- ^ Cuthill, Innes C (1997). „Ultraviolet vision in birds”. Ур.: Peter J.B. Slater. Advances in the Study of Behavior. 29. Oxford, England: Academic Press. стр. 161. ISBN 978-0-12-004529-7.

- ^ Jamieson, Barrie G. M. (2007). Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Birds. Charlottesville VA: University of Virginia. стр. 128. ISBN 978-1-57808-386-2.

- ^ Skorupski, Peter; Chittka, Lars (10. 8. 2010). „Photoreceptor Spectral Sensitivity in the Bumblebee, Bombus impatiens (Hymenoptera: Apidae)”. PLoS ONE. 5 (8): e12049. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512049S. PMC 2919406

. PMID 20711523. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012049.

. PMID 20711523. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012049.

- ^ Varela, F. J.; Palacios, A. G.; Goldsmith T. M. (1993) "Color vision of birds", pp. 77–94 in Vision, Brain, and Behavior in Birds, eds. Zeigler, Harris Philip and Bischof, Hans-Joachim. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262240369

- ^ „True or False? "The common goldfish is the only animal that can see both infra-red and ultra-violet light."”. Skeptive. 2013. Архивирано из оригинала 24. 12. 2013. г. Приступљено 28. 9. 2013.

- ^ Neumeyer, Christa (2012). „Chapter 2: Color Vision in Goldfish and Other Vertebrates”. Ур.: Lazareva, Olga; Shimizu, Toru; Wasserman, Edward. How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision. Oxford Scholarship Online. ISBN 978-0-19-533465-4.

- ^ Kasparson, A. A; Badridze, J; Maximov, V. V (2013). „Colour cues proved to be more informative for dogs than brightness”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1766): 20131356. PMC 3730601

. PMID 23864600. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1356.

. PMID 23864600. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1356.

- ^ Newman, EA; Hartline, PH (1981). „Integration of visual and infrared information in bimodal neurons in the rattlesnake optic tectum”. Science. 213 (4509): 789—91. Bibcode:1981Sci...213..789N. PMC 2693128

. PMID 7256281. doi:10.1126/science.7256281.

. PMID 7256281. doi:10.1126/science.7256281.

- ^ Kardong, KV; Mackessy, SP (1991). „The strike behavior of a congenitally blind rattlesnake”. Journal of Herpetology. 25 (2): 208—211. JSTOR 1564650. doi:10.2307/1564650.

- ^ Fang, Janet (14. 3. 2010). „Snake infrared detection unravelled”. Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2010.122.

- ^ Krochmal, Aaron R.; George S. Bakken; Travis J. LaDuc (15. 11. 2004). „Heat in evolution's kitchen: evolutionary perspectives on the functions and origin of the facial pit of pitvipers (Viperidae: Crotalinae)”. Journal of Experimental Biology. 207 (Pt 24): 4231—4238. PMID 15531644. doi:10.1242/jeb.01278.

- ^ Greene HW. (1992). "The ecological and behavioral context for pitviper evolution", in Campbell JA, Brodie ED Jr. Biology of the Pitvipers. Texas: Selva. ISBN 0-9630537-0-1.

- ^ Bruno, Thomas J. and Svoronos, Paris D. N. (2005). CRC Handbook of Fundamental Spectroscopic Correlation Charts. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420037685

- ^ Velimir Kruz: "Tehnička fizika za tehničke škole", "Školska knjiga" Zagreb, 1969.