Тврдоћа по Мосовој скали — разлика између измена

. ознака: везе до вишезначних одредница |

|||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{short description|Квалитативна скала која карактерише отпорност на огреботине}}{{рут}} |

|||

'''Мосова скала тврдоће''' је скала од 10 степени којом се одређује релативна тврдина минерала. Измислио ју је [[Немачка|немачки]] минералог [[Фридрих Мос]] [[1812]]. године. |

|||

[[File:Mohssche-haerteskala hg.jpg|thumb|250п|alt=Open wooden box with ten compartments, each containing a numbered mineral specimen.|Mohs hardness kit, containing one specimen of each mineral on the ten-point hardness scale]] |

|||

Тврдина појединачних [[минерал]]а у овој скали није сложена пропорцијално. Ова скала је једна од оријентационих скала, а класификација се заснива на томе да ако испитивани [[минерал]] може да огребе површину узорка, биће класификован његовом тврдоћом. |

'''Мосова скала тврдоће''' је скала од 10 степени којом се одређује релативна тврдина минерала. Измислио ју је [[Немачка|немачки]] минералог [[Фридрих Мос]] [[1812]]. године. Тврдина појединачних [[минерал]]а у овој скали није сложена пропорцијално. Ова скала је једна од оријентационих скала, а класификација се заснива на томе да ако испитивани [[минерал]] може да огребе површину узорка, биће класификован његовом тврдоћом. |

||

У овој скали минерали су поређани од најмекшег до најтврђег. ''Пример испитивања релативне тврдине минерала:'' Ако минерал који се испитује може да огребе површину [[кварц]]а а и кварц може њега онда ће имати кварцову тврдину, односно, тврдину 7 по Мосовој скали. Уколико минерал који испитујемо може да огребе кварц, а овај не може испитивани минерал онда ће његова тврдоћа бити већа од 7, а уколико исти минерал не може да огребе топаз (топаз има тврдину 8 по Мосовој скали) усваја се да је тврдоћа овог минерала по Мосовој скали 7,5. |

|||

У овој скали минерали су поређани од најмекшег до најтврђег. |

|||

The scale was introduced in 1822 by the German [[geologist]] and [[Mineralogy|mineralogist]] [[Friedrich Mohs]], in his ''Treatise on Mineralogy'';<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mohs|first1=Friedrich|title=Treatise on Mineralogy: Or, The Natural History of the Mineral Kingdom |translator-last1=Haidinger |translator-first1=William |location=United Kingdom |publisher=A. Constable and Company |year=1825 |orig-date=Original German publication in 1822|page=v |url=https://www.google.com/books/edition/Treatise_on_Mineralogy/BpBFAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=mohs,+treatise+on+mineralogy&pg=PR4&printsec=frontcover |access-date=11 February 2022}}</ref><ref name="USGSMineralGem">{{cite web |title=Mineral gemstones |date=18 June 1997 |publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]] |url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/gemstones/mineral.html |access-date=10 February 2021}}</ref> it is one of several definitions of [[Hardness comparison|hardness]] in [[materials science]], some of which are more quantitative.<ref name="MinSocAm">{{cite web |title=Mohs scale of hardness |publisher=[[Mineralogical Society of America]] |url=http://www.minsocam.org/MSA/collectors_corner/article/mohs.htm |access-date=10 February 2021}}</ref> |

|||

''Пример испитивања релативне тврдине минерала:'' Ако минерал који се испитује може да огребе површину [[кварц]]а а и кварц може њега онда ће имати кварцову тврдину, односно, тврдину 7 по Мосовој скали. Уколико минерал који испитујемо може да огребе кварц, а овај не може испитивани минерал онда ће његова тврдоћа бити већа од 7, а уколико исти минерал не може да огребе топаз (топаз има тврдину 8 по Мосовој скали) усваја се да је тврдоћа овог минерала по Мосовој скали 7,5. |

|||

The method of comparing hardness by observing which minerals can scratch others is of great antiquity, having been mentioned by [[Theophrastus]] in his treatise ''On Stones'', {{circa| 300 BC}}, followed by [[Pliny the Elder]] in his ''[[Natural History (Pliny)|Naturalis Historia]]'', {{circa| AD 77}}.<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.farlang.com/gemstones/theophrastus-on-stones/page_148/view?searchterm=scratch |title=Theophrastus on Stones |author=[[Theophrastus]] |via=Farlang.com |access-date=2011-12-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=[[Pliny the Elder]] |title=Naturalis Historia |chapter=Book 37, Chap. 15 |chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plin.+Nat.+37.15 |quote=''Adamas'': Six varieties of it. Two remedies.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=[[Pliny the Elder]] |title=[[Naturalis Historia]] |chapter=Book 37, Chap. 76 |chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plin.+Nat.+37.76 |quote=The methods of testing precious stones.}}</ref> The Mohs scale is useful for identification of minerals in the field, but is not an accurate predictor of how well materials endure in an industrial setting – ''toughness''.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ndt-ed.org/EducationResources/CommunityCollege/Materials/Mechanical/Hardness.htm |title=Hardness |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140214185403/http://www.ndt-ed.org/EducationResources/CommunityCollege/Materials/Mechanical/Hardness.htm |archive-date=2014-02-14 |publisher=Non-Destructive Testing Resource Center |series=Materials Mechanical Hardness}}</ref> |

|||

== Употреба == |

|||

'''Минерали који се користе за испитивање тврдоће:''' |

|||

Despite its lack of precision, the Mohs scale is relevant for field geologists, who use the scale to roughly identify minerals using scratch kits. The Mohs scale hardness of minerals can be commonly found in reference sheets. |

|||

<center> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" align=center |

|||

Mohs hardness is useful in [[Milling (machining)|milling]]. It allows assessment of which kind of mill will best reduce a given product whose hardness is known.<ref name="Milling1">{{cite web |title=Size reduction, comminution |series=Grinding and milling |publisher=PowderProcess.net |url=http://www.powderprocess.net/Grinding_Milling.html |access-date=27 October 2017}}</ref> The scale is used at electronic manufacturers for testing the resilience of flat panel display components (such as cover glass for [[Liquid-crystal display|LCD]]s or encapsulation for [[OLED]]s), as well as to evaluate the hardness of touch screens in consumer electronics.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Purdy |first=Kevin |date=16 May 2014 |title=Hardness is not toughness: Why your phone's screen may not scratch, but will shatter |magazine=Computerworld |publisher=IDG Communications Inc. |url=https://www.computerworld.com/article/2833434/hardness-is-not-toughness--why-your-phone-s-screen-may-not-scratch--but-will-shatter.html |access-date=16 April 2021}}</ref> |

|||

== Минерали == |

|||

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness is based on the ability of one natural sample of mineral to scratch another mineral visibly. The samples of matter used by Mohs are all different minerals. Minerals are chemically pure solids found in nature. Rocks are made up of one or more minerals. As the hardest known naturally occurring substance when the scale was designed, [[diamond]]s are at the top of the scale. The hardness of a material is measured against the scale by finding the hardest material that the given material can scratch, or the softest material that can scratch the given material. For example, if some material is scratched by apatite but not by fluorite, its hardness on the Mohs scale would be between 4 and 5.<ref>American Federation of Mineralogical Societies. [http://www.amfed.org/t_mohs.htm "Mohs Scale of Mineral Hardness"]. amfed.org</ref> |

|||

"Scratching" a material for the purposes of the Mohs scale means creating non-elastic dislocations visible to the naked eye. Frequently, materials that are lower on the Mohs scale can create microscopic, non-elastic dislocations on materials that have a higher Mohs number. While these microscopic dislocations are permanent and sometimes detrimental to the harder material's structural integrity, they are not considered "scratches" for the determination of a Mohs scale number.<ref>Geels, Kay. [https://web.archive.org/web/20160307194802/http://www.struers.com/resources/elements/12/2474/35art2.pdf "The True Microstructure of Materials"], pp. 5–13 in ''Materialographic Preparation from Sorby to the Present''. Struers A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark - archived Mar 7 2016</ref> |

|||

The Mohs scale is a purely [[ordinal scale]]. For example, [[corundum]] (9) is twice as hard as [[topaz]] (8), but diamond (10) is four times as hard as corundum. The table below shows the comparison with the [[absolute hardness]] measured by a [[sclerometer]], with pictorial examples.<ref>Amethyst Galleries' Mineral Gallery [https://web.archive.org/web/20061230174242/http://www.galleries.com/minerals/hardness.htm What is important about hardness?]. galleries.com</ref><ref>[http://www.inlandlapidary.com/user_area/hardness.asp Mineral Hardness and Hardness Scales] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081017152845/http://www.inlandlapidary.com/user_area/hardness.asp |date=2008-10-17 }}. Inland Lapidary</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="text-align:center" |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! |

!Мосова тврдоћа |

||

!Минерал |

|||

!style="background:#efefef;"|минерал |

|||

! |

!Хемијска формула |

||

!Апсолутна тврдоћа<ref>{{cite book|author=Mukherjee, Swapna |title=Applied Mineralogy: Applications in Industry and Environment|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mllvP7ZmWqkC&pg=PA373|date=2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-94-007-1162-4|page=373}}</ref> |

|||

!class="unsortable"|Слика |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''1''' |

|||

|<center>1</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Талк]] |

||

| |

|Mg<sub>3</sub>Si<sub>4</sub>O<sub>10</sub>(OH)<sub>2</sub> |

||

|1 |

|||

|[[Image:Talc block.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''2''' |

|||

|<center>2</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Гипс]] |

||

| |

|CaSO<sub>4</sub>·2H<sub>2</sub>O |

||

|2 |

|||

|[[Image:Gypse Arignac.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''3''' |

|||

|<center>3</center> |

|||

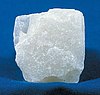

|[[ |

|[[Калцит]] |

||

| |

|CaCO<sub>3</sub> |

||

|14 |

|||

|[[Image:Calcite-sample2.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''4''' |

|||

|<center>4</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Флуорит]] |

||

| |

|CaF<sub>2</sub> |

||

|21 |

|||

|[[Image:Fluorite with Iron Pyrite.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''5''' |

|||

|<center>5</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Апатит]] |

||

| |

|Ca<sub>5</sub>(PO<sub>4</sub>)<sub>3</sub>(OH<sup>−</sup>,Cl<sup>−</sup>,F<sup>−</sup>) |

||

|48 |

|||

|[[Image:Apatite Canada.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''6''' |

|||

|<center>6</center> |

|||

|[[ортоклас]],([[фелдспат]]) |

|[[ортоклас]], ([[фелдспат]]) |

||

| |

|KAlSi<sub>3</sub>O<sub>8</sub> |

||

|72 |

|||

|[[Image:OrthoclaseBresil.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''7''' |

|||

|<center>7</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Кварц]] |

||

| |

|SiO<sub>2</sub> |

||

|100 |

|||

|[[Image:Quartz Brésil.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''8''' |

|||

|<center>8</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Топаз]] |

||

| |

|Al<sub>2</sub>SiO<sub>4</sub>(OH<sup>−</sup>,F<sup>−</sup>)<sub>2</sub> |

||

|200 |

|||

|[[Image:Topaz-120187.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''9''' |

|||

|<center>9</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Корунд]] |

||

| |

|Al<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> |

||

|400 |

|||

|[[Image:Corundum-dtn14b.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''10''' |

|||

|<center>10</center> |

|||

|[[ |

|[[Дијамант]] |

||

| |

|C |

||

|1500 |

|||

|[[Image:Rough diamond.jpg|100px]] |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

</center> |

|||

On the Mohs scale, a [[Streak (mineralogy)|streak plate]] (unglazed [[porcelain]]) has a hardness of approximately 7.0. Using these ordinary materials of known hardness can be a simple way to approximate the position of a mineral on the scale.<ref name=Brit>[https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/387714/Mohs-hardness "Mohs hardness"] in ''Encyclopædia Britannica Online''</ref> |

|||

== Средња тврдоћа == |

|||

==Литература== |

|||

The table below incorporates additional substances that may fall between levels:<ref name="Samsonov68">{{cite book | editor=Samsonov, G.V. | chapter=Mechanical Properties of the Elements | doi=10.1007/978-1-4684-6066-7 | isbn=978-1-4684-6068-1 | page=432 | title=Handbook of the Physicochemical Properties of the Elements | publisher=IFI-Plenum | place= New York | year=1968}}</ref> |

|||

{{refbegin}}-{ |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

*Mohs hardness of elements is taken from G.V. Samsonov (Ed.) in Handbook of the physicochemical properties of the elements, IFI-Plenum, New York, USA, 1968. |

|||

|- |

|||

*Cordua, William S. [http://www.gemcutters.org/LDA/hardness.htm "The Hardness of Minerals and Rocks"]. ''Lapidary Digest'', c. 1990.}- |

|||

!Hardness |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

!Substance or mineral |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|0.2–0.3 |

|||

|[[caesium]], [[rubidium]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|0.5–0.6 |

|||

|[[lithium]], [[sodium]], [[potassium]], candle wax |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|1 |

|||

|[[talc]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|1.5 |

|||

|[[gallium]], [[strontium]], [[indium]], [[tin]], [[barium]], [[thallium]], [[lead]], [[graphite]], [[ice]]<ref>[http://www.messenger-education.org/library/pdf/ice_mineral.pdf "Ice is a mineral"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151030173526/http://www.messenger-education.org/library/pdf/ice_mineral.pdf |date=2015-10-30 }} in ''Exploring Ice in the Solar System''. messenger-education.org</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|2 |

|||

|hexagonal [[boron nitride]],<ref name=berger>{{cite book|last=Berger|first=Lev I.|title=Semiconductor Materials|url=https://archive.org/details/semiconductormat0000berg|url-access=registration|year=1996|publisher=CRC Press|location=Boca Raton, FL|isbn=978-0849389122|edition=First|page=[https://archive.org/details/semiconductormat0000berg/page/126 126]}}</ref> [[calcium]], [[selenium]], [[cadmium]], [[sulfur]], [[tellurium]], [[bismuth]], [[gypsum]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|2–2.5 |

|||

|[[halite]] ([[rock salt]]), [[fingernail]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://geology.com/minerals/mohs-hardness-scale.shtml|title=Mohs Hardness Scale: Testing the Resistance to Being Scratched|website=geology.com}}</ref> [[mica]]<ref>{{Cite web|title=mica {{!}} Structure, Properties, Occurrence, & Facts|url=https://www.britannica.com/science/mica|access-date=2021-08-09|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|2.5–3 |

|||

| [[gold]], [[silver]], [[aluminium]], [[zinc]], [[lanthanum]], [[cerium]], [[Jet (lignite)|jet]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|3 |

|||

| [[calcite]], [[copper]], [[arsenic]], [[antimony]], [[thorium]], [[dentin]], [[chalk]]<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|title=Reade Advanced Materials - Mohs' Hardness (Typical) of Abrasives|url=https://www.reade.com/reade-resources/reference-educational/reade-reference-chart-particle-property-briefings/32-mohs-hardness-of-abrasives|access-date=2021-08-09|website=www.reade.com}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|3.5 |

|||

| [[platinum]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|4 |

|||

| [[fluorite]], [[iron]], [[nickel]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|4–4.5 |

|||

| ordinary [[steel]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|5 |

|||

| [[apatite]] ([[tooth enamel]]), [[zirconium]], [[palladium]], [[obsidian]] ([[volcanic glass]]) |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|5.5 |

|||

| [[beryllium]], [[molybdenum]], [[hafnium]], [[glass]], [[cobalt]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|6 |

|||

| [[orthoclase]], [[titanium]], [[manganese]], [[germanium]], [[niobium]], [[uranium]], [[rhodium]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|6–7 |

|||

| [[fused quartz]], [[iron pyrite]], [[silicon]], [[ruthenium]], [[iridium]], [[tantalum]], [[opal]], [[peridot]], [[tanzanite]], [[rhodium]], [[jade]], [[garnet]],<ref name=":0" /> [[pyrite]]<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|7 |

|||

| [[osmium]], [[quartz]], [[rhenium]], [[vanadium]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|7.5–8 |

|||

| [[emerald]], [[beryl]], [[zircon]], [[tungsten]], [[spinel]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|8 |

|||

| [[topaz]], [[cubic zirconia]], [[hardened steel]], [[spinel]]<ref>{{Cite web|title=Mohs Hardness Scale: Testing the Resistance to Being Scratched|url=https://geology.com/minerals/mohs-hardness-scale.shtml|access-date=2021-08-09|website=geology.com}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|8.5 |

|||

| [[chrysoberyl]], [[chromium]], [[silicon nitride]], [[tantalum carbide]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"| 9 |

|||

| [[corundum]] (includes [[sapphire]] and [[ruby]]), [[tungsten carbide#Physical properties|tungsten carbide]], [[titanium nitride]], [[aluminium oxide]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"| 9–9.5 |

|||

| [[silicon carbide]] (carborundum), [[tantalum carbide]], [[zirconium carbide]], [[Aluminium oxide|alumina]], [[beryllium carbide]], [[titanium carbide]], [[Aluminium boride|aluminum boride]], [[boron carbide]].<ref name=TedPellaMHT/><ref name=PraterindustriesHT/><ref name=TedPellaMHT>{{cite web |title=Material hardness tables |website=www.tedpella.com |url=https://www.tedpella.com/company_html/hardness.htm |access-date=2019-05-09}}</ref><ref name=PraterindustriesHT>{{cite web |title=Hardness table |url=https://www.praterindustries.com/wp-content/uploads/hardness-table.pdf |access-date=2019-05-09}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|9.5–near 10 |

|||

| [[boron]], [[boron nitride]], [[rhenium diboride]] (''a''-axis),<ref name=AFM>{{cite journal |last1=Levine |first1=Jonathan B. |last2=Tolbert |first2=Sarah H. |last3=Kaner |first3=Richard B. |year=2009 |title=Advancements in the search for superhard ultra-incompressible metal borides |journal=Advanced Functional Materials |volume=19 |issue=22 |pages=3526–3527 |doi=10.1002/adfm.200901257 |url=http://tolbert.chem.ucla.edu/Publication/AdvFuncMater-19-p3519.pdf |access-date=2015-12-08 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304102359/http://tolbert.chem.ucla.edu/Publication/AdvFuncMater-19-p3519.pdf |archive-date=2016-03-04}}</ref> [[stishovite]], [[titanium diboride]], [[moissanite]] (crystal form of silicon carbide), [[boron carbide]]<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center;"|10 |

|||

| [[diamond]], [[carbonado]] |

|||

|} |

|||

== Поређење са Викерсовом скалом == |

|||

{{Expand list|date=August 2017}} |

|||

Comparison between Mohs hardness and [[Vickers hardness test|Vickers hardness]]:<ref name="mindat.org">{{cite web |last=Ralph |first=Jolyon |title=Welcome to mindat.org |website=mindat.org |publisher=Hudson Institute of Mineralogy |url=https://www.mindat.org/ |access-date=April 16, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

{|class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Mineral<br/>name |

|||

! Hardness (Mohs) |

|||

! Hardness (Vickers)<br/>(kg/mm{{sup|2}}) |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Graphite]]||1–2||VHN{{sub|10}} = 7–11 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Tin]]||1.5||VHN{{sub|10}} = 7–9 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Bismuth]]||2–2.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 16–18 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Native gold|Gold]]||2.5||VHN{{sub|10}} = 30–34 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Silver]]||2.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 61–65 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Chalcocite]]||2.5–3||VHN{{sub|100}} = 84–87 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Native copper|Copper]]||2.5–3||VHN{{sub|100}} = 77–99 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Galena]]||2.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 79–104 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Sphalerite]]||3.5–4||VHN{{sub|100}} = 208–224 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Heazlewoodite]]||4||VHN{{sub|100}} = 230–254 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Carrollite]]||4.5–5.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 507–586 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Goethite]]||5–5.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 667 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Hematite]]||5–6||VHN{{sub|100}} = 1,000–1,100 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Chromite]]||5.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 1,278–1,456 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Anatase]]||5.5–6||VHN{{sub|100}} = 616–698 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Rutile]]||6–6.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 894–974 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Pyrite]]||6–6.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 1,505–1,520 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Bowieite]]||7||VHN{{sub|100}} = 858–1,288 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Euclase]]||7.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 1,310 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Chromium]]||8.5||VHN{{sub|100}} = 1,875–2,000 |

|||

|} |

|||

==Види још== |

==Види још== |

||

*[[Тврдина]] |

*[[Тврдина]] |

||

== Референце == |

|||

{{reflist|}} |

|||

== Литература == |

|||

{{refbegin|}} |

|||

* Mohs hardness of elements is taken from G.V. Samsonov (Ed.) in Handbook of the physicochemical properties of the elements, IFI-Plenum, New York, USA, 1968. |

|||

* {{cite magazine |last=Cordua |first=William S. |year=c. 1990 |title=The Hardness of Minerals and Rocks |magazine=Lapidary Digest |url=http://www.gemcutters.org/LDA/hardness.htm |via=gemcutters.org}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

{{Commonscat|Hardness}} |

* {{Commonscat-inline|Hardness}} |

||

{{нормативна контрола}} |

{{нормативна контрола}} |

||

| Ред 75: | Ред 241: | ||

[[Категорија:Минералогија]] |

[[Категорија:Минералогија]] |

||

[[Категорија:Скале]] |

[[Категорија:Скале]] |

||

[[de:Härte#Härteprüfung nach Mohs]] |

|||

Верзија на датум 4. јул 2022. у 03:16

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Мосова скала тврдоће је скала од 10 степени којом се одређује релативна тврдина минерала. Измислио ју је немачки минералог Фридрих Мос 1812. године. Тврдина појединачних минерала у овој скали није сложена пропорцијално. Ова скала је једна од оријентационих скала, а класификација се заснива на томе да ако испитивани минерал може да огребе површину узорка, биће класификован његовом тврдоћом.

У овој скали минерали су поређани од најмекшег до најтврђег. Пример испитивања релативне тврдине минерала: Ако минерал који се испитује може да огребе површину кварца а и кварц може њега онда ће имати кварцову тврдину, односно, тврдину 7 по Мосовој скали. Уколико минерал који испитујемо може да огребе кварц, а овај не може испитивани минерал онда ће његова тврдоћа бити већа од 7, а уколико исти минерал не може да огребе топаз (топаз има тврдину 8 по Мосовој скали) усваја се да је тврдоћа овог минерала по Мосовој скали 7,5.

The scale was introduced in 1822 by the German geologist and mineralogist Friedrich Mohs, in his Treatise on Mineralogy;[1][2] it is one of several definitions of hardness in materials science, some of which are more quantitative.[3]

The method of comparing hardness by observing which minerals can scratch others is of great antiquity, having been mentioned by Theophrastus in his treatise On Stones, око 300 BC, followed by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia, око AD 77.[4][5][6] The Mohs scale is useful for identification of minerals in the field, but is not an accurate predictor of how well materials endure in an industrial setting – toughness.[7]

Употреба

Despite its lack of precision, the Mohs scale is relevant for field geologists, who use the scale to roughly identify minerals using scratch kits. The Mohs scale hardness of minerals can be commonly found in reference sheets.

Mohs hardness is useful in milling. It allows assessment of which kind of mill will best reduce a given product whose hardness is known.[8] The scale is used at electronic manufacturers for testing the resilience of flat panel display components (such as cover glass for LCDs or encapsulation for OLEDs), as well as to evaluate the hardness of touch screens in consumer electronics.[9]

Минерали

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness is based on the ability of one natural sample of mineral to scratch another mineral visibly. The samples of matter used by Mohs are all different minerals. Minerals are chemically pure solids found in nature. Rocks are made up of one or more minerals. As the hardest known naturally occurring substance when the scale was designed, diamonds are at the top of the scale. The hardness of a material is measured against the scale by finding the hardest material that the given material can scratch, or the softest material that can scratch the given material. For example, if some material is scratched by apatite but not by fluorite, its hardness on the Mohs scale would be between 4 and 5.[10]

"Scratching" a material for the purposes of the Mohs scale means creating non-elastic dislocations visible to the naked eye. Frequently, materials that are lower on the Mohs scale can create microscopic, non-elastic dislocations on materials that have a higher Mohs number. While these microscopic dislocations are permanent and sometimes detrimental to the harder material's structural integrity, they are not considered "scratches" for the determination of a Mohs scale number.[11]

The Mohs scale is a purely ordinal scale. For example, corundum (9) is twice as hard as topaz (8), but diamond (10) is four times as hard as corundum. The table below shows the comparison with the absolute hardness measured by a sclerometer, with pictorial examples.[12][13]

| Мосова тврдоћа | Минерал | Хемијска формула | Апсолутна тврдоћа[14] | Слика |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Талк | Mg3Si4O10(OH)2 | 1 |

|

| 2 | Гипс | CaSO4·2H2O | 2 |

|

| 3 | Калцит | CaCO3 | 14 |

|

| 4 | Флуорит | CaF2 | 21 |

|

| 5 | Апатит | Ca5(PO4)3(OH−,Cl−,F−) | 48 |

|

| 6 | ортоклас, (фелдспат) | KAlSi3O8 | 72 |

|

| 7 | Кварц | SiO2 | 100 |

|

| 8 | Топаз | Al2SiO4(OH−,F−)2 | 200 |

|

| 9 | Корунд | Al2O3 | 400 |

|

| 10 | Дијамант | C | 1500 |

|

On the Mohs scale, a streak plate (unglazed porcelain) has a hardness of approximately 7.0. Using these ordinary materials of known hardness can be a simple way to approximate the position of a mineral on the scale.[15]

Средња тврдоћа

The table below incorporates additional substances that may fall between levels:[16]

Поређење са Викерсовом скалом

Шаблон:Expand list Comparison between Mohs hardness and Vickers hardness:[26]

| Mineral name |

Hardness (Mohs) | Hardness (Vickers) (kg/mm2) |

|---|---|---|

| Graphite | 1–2 | VHN10 = 7–11 |

| Tin | 1.5 | VHN10 = 7–9 |

| Bismuth | 2–2.5 | VHN100 = 16–18 |

| Gold | 2.5 | VHN10 = 30–34 |

| Silver | 2.5 | VHN100 = 61–65 |

| Chalcocite | 2.5–3 | VHN100 = 84–87 |

| Copper | 2.5–3 | VHN100 = 77–99 |

| Galena | 2.5 | VHN100 = 79–104 |

| Sphalerite | 3.5–4 | VHN100 = 208–224 |

| Heazlewoodite | 4 | VHN100 = 230–254 |

| Carrollite | 4.5–5.5 | VHN100 = 507–586 |

| Goethite | 5–5.5 | VHN100 = 667 |

| Hematite | 5–6 | VHN100 = 1,000–1,100 |

| Chromite | 5.5 | VHN100 = 1,278–1,456 |

| Anatase | 5.5–6 | VHN100 = 616–698 |

| Rutile | 6–6.5 | VHN100 = 894–974 |

| Pyrite | 6–6.5 | VHN100 = 1,505–1,520 |

| Bowieite | 7 | VHN100 = 858–1,288 |

| Euclase | 7.5 | VHN100 = 1,310 |

| Chromium | 8.5 | VHN100 = 1,875–2,000 |

Види још

Референце

- ^ Mohs, Friedrich (1825). Treatise on Mineralogy: Or, The Natural History of the Mineral Kingdom. Превод: Haidinger, William. United Kingdom: A. Constable and Company. стр. v. Приступљено 11. 2. 2022. Непознати параметар

|orig-date=игнорисан (помоћ) - ^ „Mineral gemstones”. United States Geological Survey. 18. 6. 1997. Приступљено 10. 2. 2021.

- ^ „Mohs scale of hardness”. Mineralogical Society of America. Приступљено 10. 2. 2021.

- ^ Theophrastus. Theophrastus on Stones. Приступљено 2011-12-10 — преко Farlang.com.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. „Book 37, Chap. 15”. Naturalis Historia. „'Adamas: Six varieties of it. Two remedies.”

- ^ Pliny the Elder. „Book 37, Chap. 76”. Naturalis Historia. „The methods of testing precious stones.”

- ^ „Hardness”. Materials Mechanical Hardness. Non-Destructive Testing Resource Center. Архивирано из оригинала 2014-02-14. г.

- ^ „Size reduction, comminution”. Grinding and milling. PowderProcess.net. Приступљено 27. 10. 2017.

- ^ Purdy, Kevin (16. 5. 2014). „Hardness is not toughness: Why your phone's screen may not scratch, but will shatter”. Computerworld. IDG Communications Inc. Приступљено 16. 4. 2021.

- ^ American Federation of Mineralogical Societies. "Mohs Scale of Mineral Hardness". amfed.org

- ^ Geels, Kay. "The True Microstructure of Materials", pp. 5–13 in Materialographic Preparation from Sorby to the Present. Struers A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark - archived Mar 7 2016

- ^ Amethyst Galleries' Mineral Gallery What is important about hardness?. galleries.com

- ^ Mineral Hardness and Hardness Scales Архивирано 2008-10-17 на сајту Wayback Machine. Inland Lapidary

- ^ Mukherjee, Swapna (2012). Applied Mineralogy: Applications in Industry and Environment. Springer Science & Business Media. стр. 373. ISBN 978-94-007-1162-4.

- ^ "Mohs hardness" in Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ Samsonov, G.V., ур. (1968). „Mechanical Properties of the Elements”. Handbook of the Physicochemical Properties of the Elements. New York: IFI-Plenum. стр. 432. ISBN 978-1-4684-6068-1. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-6066-7.

- ^ "Ice is a mineral" Архивирано 2015-10-30 на сајту Wayback Machine in Exploring Ice in the Solar System. messenger-education.org

- ^ Berger, Lev I. (1996). Semiconductor Materials

(First изд.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. стр. 126. ISBN 978-0849389122.

(First изд.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. стр. 126. ISBN 978-0849389122.

- ^ „Mohs Hardness Scale: Testing the Resistance to Being Scratched”. geology.com.

- ^ „mica | Structure, Properties, Occurrence, & Facts”. Encyclopedia Britannica (на језику: енглески). Приступљено 2021-08-09.

- ^ а б в г „Reade Advanced Materials - Mohs' Hardness (Typical) of Abrasives”. www.reade.com. Приступљено 2021-08-09.

- ^ „Mohs Hardness Scale: Testing the Resistance to Being Scratched”. geology.com. Приступљено 2021-08-09.

- ^ а б „Material hardness tables”. www.tedpella.com. Приступљено 2019-05-09.

- ^ а б „Hardness table” (PDF). Приступљено 2019-05-09.

- ^ Levine, Jonathan B.; Tolbert, Sarah H.; Kaner, Richard B. (2009). „Advancements in the search for superhard ultra-incompressible metal borides” (PDF). Advanced Functional Materials. 19 (22): 3526—3527. doi:10.1002/adfm.200901257. Архивирано из оригинала (PDF) 2016-03-04. г. Приступљено 2015-12-08.

- ^ Ralph, Jolyon. „Welcome to mindat.org”. mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Приступљено 16. 4. 2017.

Литература

- Mohs hardness of elements is taken from G.V. Samsonov (Ed.) in Handbook of the physicochemical properties of the elements, IFI-Plenum, New York, USA, 1968.

- Cordua, William S. (c. 1990). „The Hardness of Minerals and Rocks”. Lapidary Digest — преко gemcutters.org.

Спољашње везе

Медији везани за чланак Тврдоћа по Мосовој скали на Викимедијиној остави

Медији везани за чланак Тврдоћа по Мосовој скали на Викимедијиној остави