Хумор — разлика између измена

мНема описа измене |

. ознака: везе до вишезначних одредница |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

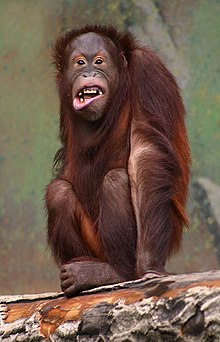

[[Датотека:Eduard von Grützner Falstaff.jpg|мини|Осмех]] |

[[Датотека:Eduard von Grützner Falstaff.jpg|мини|Осмех]] |

||

'''Хумор''' ({{јез-лат|humor}} – [[влажност]], [[течност]], сок из средњовековне [[физиологија|физиологије]]), '''увесељење''' или '''духовитост''' је способност [[човек|људи]], објеката или ситуација да изазове осећај [[забава|забаве]] у другим људима. Тај [[осећање|осећај]] углавном прати [[осмех]] или гласан смех, веома здрав за организам. Порекло речи хумор долази од хуморалног лечења [[античка Грчка|старих Грка]], који су тврдили да мешавина течности (хумора) контролише људско здравље и осећаје. Ова тврдња је касније оповргнута, дефинишући хумор као снажну емоцију која се јавља у случају комичних ситуација у којима се особа осећа надмоћно, или на било који начин бољом од [[човек|људи]], или објеката који изводи шалу. |

'''Хумор''' ({{јез-лат|humor}} – [[влажност]], [[течност]], сок из средњовековне [[физиологија|физиологије]]), '''увесељење''' или '''духовитост''' је способност [[човек|људи]], објеката или ситуација да изазове осећај [[забава|забаве]] у другим људима. Тај [[осећање|осећај]] углавном прати [[осмех]] или гласан смех, веома здрав за организам. Порекло речи хумор долази од хуморалног лечења [[античка Грчка|старих Грка]], који су тврдили да мешавина течности (хумора) контролише људско здравље и осећаје. Ова тврдња је касније оповргнута, дефинишући хумор као снажну емоцију која се јавља у случају комичних ситуација у којима се особа осећа надмоћно, или на било који начин бољом од [[човек|људи]], или објеката који изводи шалу. |

||

==Теорије== |

|||

{{rut}} |

|||

Many theories exist about what humour is and what social function it serves. The prevailing types of theories attempting to account for the existence of humour include [[psychology|psychological]] theories, the vast majority of which consider humour-induced behaviour to be very healthy; spiritual theories, which may, for instance, consider humour to be a "gift from God"; and theories which consider humour to be an unexplainable mystery, very much like a [[mysticism|mystical experience]].<ref>[[Raymond Smullyan]], "The Planet Without Laughter", ''[[This Book Needs No Title]]''</ref> |

|||

The benign-violation theory, endorsed by [[Peter McGraw]], attempts to explain humour's existence. The theory says 'humour only occurs when something seems wrong, unsettling, or threatening, but simultaneously seems okay, acceptable or safe'.<ref>[[Peter McGraw]], "Too close for Comfort, or Too Far to care? Finding Humor in Distant Tragedies and Close Mishaps"</ref> Humour can be used as a method to easily engage in social interaction by taking away that awkward, uncomfortable, or uneasy feeling of social interactions. |

|||

Others believe that 'the appropriate use of humour can facilitate social interactions'.<ref>[[Nicholas Kuiper]], "Prudence and Racial Humor: Troubling Epithets" </ref> |

|||

== Гледишта == |

|||

Some claim that humour should not be explained. Author [[E. B. White]] once said, "Humor can be dissected as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.quotationspage.com/quote/984.html|title=The Quotations Page: Quote from E.B. White|access-date=26 August 2018}}</ref> Counter to this argument, protests against "offensive" cartoons invite the dissection of humour or its lack by aggrieved individuals and communities. This process of dissecting humour does not necessarily banish a sense of humour but directs attention towards its politics and assumed universality.<ref>Ritu Gairola Khanduri. 2014. [http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/authors/246935 Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History of the Modern World]. Cambridge: [[Cambridge University Press]].</ref> |

|||

Non-satirical humour can be specifically termed ''droll humour'' or ''recreational drollery''.<ref>Seth Benedict Graham ''[http://etd.library.pitt.edu/ETD/available/etd-11032003-192424/unrestricted/grahamsethb_etd2003.pdf A cultural analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot]'' 2003 p. 13</ref><ref>Bakhtin, Mikhail. ''Rabelais and His World'' [1941, 1965]. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press p. 12</ref> |

|||

== Порекло појма == |

== Порекло појма == |

||

| Ред 8: | Ред 23: | ||

== Историја == |

== Историја == |

||

Хумор се појављује још у раној историји. У ''[[Библија|Светоме писму]]'' [[Илија (пророк)|пророк Илија]] иронично саопштава идолопоклоницима бога [https://sr.wikipedia.org/sr-ec/%D0%91%D0%B0%D0%B0%D0%BB Вала]:<blockquote>„А кад би у подне, стаде им се ругати Илија говорећи: вичите већма; јер је он бог! ваљда се нешто замислио, или је у послу, или на путу, или може бити да спава, да се пробуди.” ([[Прва књига о царевима|1 цар]], 18, 27)</blockquote> |

Хумор се појављује још у раној историји. У ''[[Библија|Светоме писму]]'' [[Илија (пророк)|пророк Илија]] иронично саопштава идолопоклоницима бога [https://sr.wikipedia.org/sr-ec/%D0%91%D0%B0%D0%B0%D0%BB Вала]:<blockquote>„А кад би у подне, стаде им се ругати Илија говорећи: вичите већма; јер је он бог! ваљда се нешто замислио, или је у послу, или на путу, или може бити да спава, да се пробуди.” ([[Прва књига о царевима|1 цар]], 18, 27)</blockquote> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

== Врсте хумора (шала) == |

== Врсте хумора (шала) == |

||

{{colbegin|colwidth=20em}} |

|||

* Вербалне форме |

* Вербалне форме |

||

** [[Иронија]] |

** [[Иронија]] |

||

| Ред 16: | Ред 33: | ||

** [[Parodija|Пародија]] |

** [[Parodija|Пародија]] |

||

** [[Шала|Виц]] |

** [[Шала|Виц]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* Невербалне |

* Невербалне |

||

** [[Гримасе]] (пример [[Џим Кери]]) |

** [[Гримасе]] (пример [[Џим Кери]]) |

||

| Ред 27: | Ред 43: | ||

* Одећа и костими |

* Одећа и костими |

||

* Смешни звукови |

* Смешни звукови |

||

{{colend}} |

|||

== At school == |

|||

The use of humour plays an important role in youth development.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Legkauskas, V.)), ((Magelinskaitė-Legkauskienė, Š.)) | journal=Early Child Development and Care | title=Social competence in the 1st grade predicts school adjustment two years later | volume=191 | issue=1 | pages=83–92 | date= 2021 | url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1603149 | issn=0300-4430 | doi=10.1080/03004430.2019.1603149| s2cid=150567697 }}</ref> Studies have shown that humour is especially important in social interactions with peers.<ref name="Burger">{{cite journal | vauthors=((Burger, C.)) | journal=International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | title=Humor styles, bullying victimization and psychological school adjustment: Mediation, moderation and person-oriented analyses | volume=19 | issue=18 | pages=11415 | date= 2022 | issn=1661-7827 | doi=10.3390/ijerph191811415| pmid= | pmc= | doi-access=free }}</ref> School entry is the time when the importance of parents fades into the background and social interaction with peers becomes increasingly important. Conflict is inherent in these interactions. The use of humour plays an important role in conflict resolution and ultimately in school success and psychological adjustment.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Kiuru, N.)), ((Wang, M.-T.)), ((Salmela-Aro, K.)), ((Kannas, L.)), ((Ahonen, T.)), ((Hirvonen, R.)) | journal=Journal of Youth and Adolescence | title=Associations between adolescents' interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions | volume=49 | issue=5 | pages=1057–1072 | date= 2020 | url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01184-y | issn=0047-2891 | doi=10.1007/s10964-019-01184-y| pmid= | pmc= }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors=((Søndergaard, D. M.)) | journal=Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour | title=The thrill of bullying. Bullying, humour and the making of community | volume=48 | issue=1 | pages=48–65 | date= 2018 | url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12153 | issn=0021-8308 | doi=10.1111/jtsb.12153}}</ref> The use of humour that is socially acceptable leads to a lower likelihood of being a victim of bullying, whereas the use of self-disparaging humour leads to a higher likelihood of being bullied.<ref name="Burger"/> When students are bullied, the use of self-disparaging humour can lead to an exacerbation of the negative effects on the student's psychological adjustment to school.<ref name="Burger"/> |

|||

== Studies == |

|||

=== Laughter === |

|||

[[File:Killian Couppey.jpg|thumb|upright|A man laughing]] |

|||

One of the main focuses of modern psychological humour theory and research is to establish and clarify the correlation between humour and laughter. The major empirical findings here are that [[laughter]] and humour do not always have a one-to-one association. While most previous theories assumed the connection between the two almost to the point of them being synonymous, psychology has been able to scientifically and empirically investigate the supposed connection, its implications, and significance. |

|||

In 2009, Diana Szameitat conducted a study to examine the differentiation of emotions in laughter. They hired actors and told them to laugh with one of four different emotional associations by using auto-induction, where they would focus exclusively on the internal emotion and not on the expression of laughter itself. They found an overall recognition rate of 44%, with joy correctly classified at 44%, [[Tickling|tickle]] 45%, [[schadenfreude]] 37%, and taunt 50%.<ref name="Szameitat2009">Szameitat, Diana P., et al. Differentiation of Emotions in Laughter at the Behavioural Level. 2009 Emotion 9 (3).</ref>{{rp|399}} Their second experiment tested the behavioural recognition of laughter during an induced emotional state and they found that different laughter types did differ with respect to emotional dimensions.<ref name="Szameitat2009" />{{rp|401–402}} In addition, the four emotional states displayed a full range of high and low sender arousal and valence.<ref name="Szameitat2009" />{{rp|403}} This study showed that laughter can be correlated with both positive (joy and tickle) and negative (schadenfreude and taunt) emotions with varying degrees of arousal in the subject. |

|||

=== Health === |

|||

Adaptive Humour use has shown to be effective for increasing resilience in dealing with distress and also effective in buffering against or undoing negative affects. In contrast, maladaptive humour use can magnify potential negative effects.<ref name="Burger"/> |

|||

Madeljin Strick, Rob Holland, Rick van Baaren, and Ad van Knippenberg (2009) of Radboud University conducted a study that showed the distracting nature of a joke on bereaved individuals.<ref name="Strick">{{cite journal | last1 = Strick | first1 = Madelijn | display-authors = etal | year = 2009| title = Finding Comfort in a Joke: Consolatory Effects of Humor Through Cognitive Distraction | doi = 10.1037/a0015951 | pmid = 19653782 | journal = Emotion | volume = 9 | issue = 4 | pages = 574–578 | s2cid = 14369631 | url = https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6f619548c28361ab18e6ea46ea611c03517fdad6 }}</ref>{{rp|574–578}} Subjects were presented with a wide range of negative pictures and sentences. Their findings showed that humorous therapy attenuated the negative emotions elicited after negative pictures and sentences were presented. In addition, the humour therapy was more effective in reducing negative affect as the degree of affect increased in intensity.<ref name="Strick" />{{rp|575–576}} Humour was immediately effective in helping to deal with distress. The escapist nature of humour as a coping mechanism suggests that it is most useful in dealing with momentary stresses. Stronger negative stimuli requires a different therapeutic approach. |

|||

Studies, such as those testing the [[undoing (psychology)|undoing hypothesis]],<ref name="Fredrickson">{{cite journal | last1 = Fredrickson | first1 = Barbara L. | year = 1998| title = What Good Are Positive Emotions? | doi = 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300 | journal = Review of General Psychology | volume = 2 | issue = 3| pages = 300–319 | pmid=21850154 | pmc=3156001}}</ref>{{rp|313}} have shown several positive outcomes of humour as an underlying positive trait in amusement and playfulness. Several studies have shown that positive emotions can restore autonomic quiescence after negative affect. For example, Frederickson and Levinson showed that individuals who expressed [[Smile#Duchenne smile|Duchenne smiles]] during the negative arousal of a sad and troubling event recovered from the negative affect approximately 20% faster than individuals who didn't smile.<ref name="Fredrickson" />{{rp|314}} |

|||

Using humour judiciously can have a positive influence on cancer treatment.<ref>{{cite web|access-date=22 January 2017|url=https://allusdoctors.com/cancer-treatment/humor-in-cancer|title=Humor in Cancer Treatment}}</ref> The effectiveness for humour‐based interventions in patients with schizophrenia is uncertain in a Cochrane review.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Tsujimoto | first1 = Y. | last2 = Nakamura | first2 = Y. | display-authors = etal | year = 2021 | title = Humour‐based interventions for people with schizophrenia | journal = Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2021 | issue = 10 | pages = CD013367 | doi=10.1002/14651858.CD013367.pub2| pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> |

|||

Humour can serve as a strong distancing mechanism in coping with adversity. In 1997, Kelter and Bonanno found that Duchenne laughter correlated with reduced awareness of distress.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Keltner | first1 = D. | last2 = Bonanno | first2 = G. A. | year = 1997 | title = A study of laughter and dissociation: Distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement | journal = Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | volume = 73 | issue = 4| pages = 687–702 | doi=10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.687| pmid = 9325589 }}</ref> Positive emotion is able to loosen the grip of negative emotions on people’s thinking. A distancing of thought leads to a distancing of the unilateral responses people often have to negative arousal. In parallel with the distancing role plays in coping with distress, it supports the [[broaden and build]] theory that positive emotions lead to increased multilateral cognitive pathway and social resource building. |

|||

== Види још == |

== Види још == |

||

* [[Хумореска]] |

* [[Хумореска]] |

||

== Референце == |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== Лиратура == |

|||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* Alexander, Richard (1984), ''Verbal humor and variation in English: Sociolinguistic notes on a variety of jokes'' |

|||

* Alexander, Richard (1997), ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=zioy07JVHcwC Aspects of verbal humour in English]'' |

|||

* {{citation | last = Basu | first =S | title= Dialogic ethics and the virtue of humor | journal =Journal of Political Philosophy | date= December 1999 | volume =7 | issue =4 | pages =378–403 | url=http://www.anthrosource.net/doi/abs/10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14 | doi =10.1111/1467-9760.00082 | access-date =2007-07-06 }} (Abstract) |

|||

* Billig, M. (2005). ''Laughter and ridicule: Towards a social critique of humour''. London: Sage. {{ISBN|1-4129-1143-5}} |

|||

* Bricker, Victoria Reifler (Winter, 1980) ''[https://www.jstor.org/stable/3629610 The Function of Humor in Zinacantan]'' Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 411–418 |

|||

* {{Citation | last1 =Buijzen | first1 =Moniek | last2 =Valkenburg | first2 =Patti M. | title =Developing a Typology of Humor in Audiovisual Media | journal =Media Psychology | volume =6 | issue =2 | pages =147–167 | year= 2004 | doi =10.1207/s1532785xmep0602_2 | s2cid =96438940}}(Abstract) |

|||

* Carrell, Amy (2000), ''[https://web.archive.org/web/20070928094655/http://www.uni-duesseldorf.de/WWW/MathNat/Ruch/PSY356-Webarticles/Historical_Views.pdf Historical views of humour]'', University of Central Oklahoma. Retrieved on 2007-07-06. |

|||

* {{Citation | last1 =García-Barriocanal | first1 =Elena | last2 =Sicilia | first2 =Miguel-Angel | last3 =Palomar | first3 =David | title =A Graphical Humor Ontology for Contemporary Cultural Heritage Access | publisher =University of Alcalá | location =Madrid | year =2005 | url =http://is2.lse.ac.uk/asp/aspecis/20050064.pdf | access-date =2007-07-06 | url-status=dead | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20060523215950/http://is2.lse.ac.uk/asp/aspecis/20050064.pdf | archive-date =2006-05-23 }} |

|||

* Goldstein, Jeffrey H., et al. (1976) "Humour, Laughter, and Comedy: A Bibliography of Empirical and Nonempirical Analyses in the English Language." ''It's a Funny Thing, Humour''. Ed. Antony J. Chapman and Hugh C. Foot. Oxford and New York: Pergamon Press, 1976. 469–504. |

|||

* Hurley, Matthew M., Dennett, Daniel C., and Adams, Reginald B. Jr. (2011), ''Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. {{ISBN|978-0-262-01582-0}} |

|||

* Holland, Norman. (1982) "Bibliography of Theories of Humor." ''Laughing; A Psychology of Humor''. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 209–223. |

|||

* Martin, Rod A. (2007). ''The Psychology Of Humour: An Integrative Approach.'' London, UK: Elsevier Academic Press. {{ISBN|978-0-12-372564-6}} |

|||

* McGhee, Paul E. (1984) "Current American Psychological Research on Humor." Jahrbuche fur Internationale Germanistik 16.2: 37–57. |

|||

* Mintz, Lawrence E., ed. (1988) ''Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics''. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1988. {{ISBN|0-313-24551-7}}; {{OCLC|16085479}}. |

|||

* {{Citation | last1 = Mobbs | first1 = D. | last2 = Greicius | first2 = M. D. | last3 = Abdel-Azim | first3 = E. | last4 = Menon | first4 = V. | last5 = Reiss | first5 = A. L. | year = 2003 | title = Humor modulates the mesolimbic reward centres | journal = Neuron | pmid = 14659102 | volume = 40 | issue = 5| pages = 1041–1048 | postscript = . |doi = 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00751-7| doi-access = free }} |

|||

* Nilsen, Don L. F. (1992) "Satire in American Literature." ''Humor in American Literature: A Selected Annotated Bibliography.'' New York: Garland, 1992. 543–48. |

|||

* Pogel, Nancy; and Paul P. Somers Jr. (1988) "Literary Humor." ''Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics''. Ed. Lawrence E. Mintz. London: Greenwood, 1988. 1–34. |

|||

* {{cite journal | last1 = Roth | first1 = G. | last2 = Yap | first2 = R. | last3 = Short | first3 = D. | year = 2006 | title = Examining humour in HRD from theoretical and practical perspectives | journal = Human Resource Development International | volume = 9 | issue = 1| pages = 121–127 | doi=10.1080/13678860600563424| s2cid = 143854518 }} |

|||

* Smuts, Aaron. "Humor". ''[http://www.iep.utm.edu/h/humor.htm Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]'' |

|||

* {{citation | last = Wogan | first = Peter | title = Laughing At ''First Contact'' | journal = Visual Anthropology Review | date =Spring 2006 | volume = 22 | issue = 1 | pages =14–34 | publication-date = 12 December 2006 | doi = 10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14 }} |

|||

* Wild, B., Rodden, F.A., Grodd, W., & Ruch, W. (2003). Neural correlates of laughter and humour<!--[sic]-->. ''Brain'', 126, 2121-1238. |

|||

* Goel, V., & Dolan, R. (2001). The functional anatomy of humor: Segregating cognitive and affective components. ''Nature Neuroscience'', 4(3), 237-8. |

|||

* Gervais, M. & Wilson, D., 2005. The evolution and functions of laughter and humor: A synthetic approach. ''The Quarterly Review of Biology''. 80(4), 395-430 |

|||

* Spoor, J. R. & Kelly, J. R. (2004). The evolutionary significance of affect in groups: Communication and group bonding. ''Group Processes and Intergroup Relations'', 7, 398-412 |

|||

* Neuhoff, C. & Shaeffer, C. (2002). Effects of laughing, smiling, and howling on mood. ''Psychological Reports'', 91, 1079-1080 |

|||

* {{cite journal | vauthors=((Burger, C.)) | journal=International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | title=Humor styles, bullying victimization and psychological school adjustment: Mediation, moderation and person-oriented analyses | volume=19 | issue=18 | pages=11415 | date= 2022 | issn=1661-7827 | doi=10.3390/ijerph191811415| pmid= | pmc= | doi-access=free }} |

|||

* Robinson, L. (2020, October). Laughter is the Best Medicine. https://www.helpguide.org/articles/mental-health/laughter-is-the-best-medicine.htm {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220218220940/https://www.helpguide.org/articles/mental-health/laughter-is-the-best-medicine.htm |date=2022-02-18 }} |

|||

* Henry Ford Health System Staff. How Laughter Benefits Your Heart Health. https://www.henryford.com/blog/2019/03/how-laughter-benefits-heart-health#:~:text=Reduces%20blood%20pressure.,takes%20tension%20off%20your%20heart {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211006234944/https://www.henryford.com/blog/2019/03/how-laughter-benefits-heart-health#:~:text=Reduces%20blood%20pressure.,takes%20tension%20off%20your%20heart |date=2021-10-06 }} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

{{Commonscat|Humor}} |

{{Commonscat|Humor}} |

||

* {{Curlie|Recreation/Humor/|Humor}} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20100111121416/http://www.hnu.edu/ishs/ International Society for Humor Studies] |

|||

{{клица}} |

|||

{{нормативна контрола}} |

{{нормативна контрола}} |

||

Верзија на датум 6. април 2023. у 05:46

Хумор (лат. humor – влажност, течност, сок из средњовековне физиологије), увесељење или духовитост је способност људи, објеката или ситуација да изазове осећај забаве у другим људима. Тај осећај углавном прати осмех или гласан смех, веома здрав за организам. Порекло речи хумор долази од хуморалног лечења старих Грка, који су тврдили да мешавина течности (хумора) контролише људско здравље и осећаје. Ова тврдња је касније оповргнута, дефинишући хумор као снажну емоцију која се јавља у случају комичних ситуација у којима се особа осећа надмоћно, или на било који начин бољом од људи, или објеката који изводи шалу.

Теорије

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Many theories exist about what humour is and what social function it serves. The prevailing types of theories attempting to account for the existence of humour include psychological theories, the vast majority of which consider humour-induced behaviour to be very healthy; spiritual theories, which may, for instance, consider humour to be a "gift from God"; and theories which consider humour to be an unexplainable mystery, very much like a mystical experience.[1]

The benign-violation theory, endorsed by Peter McGraw, attempts to explain humour's existence. The theory says 'humour only occurs when something seems wrong, unsettling, or threatening, but simultaneously seems okay, acceptable or safe'.[2] Humour can be used as a method to easily engage in social interaction by taking away that awkward, uncomfortable, or uneasy feeling of social interactions.

Others believe that 'the appropriate use of humour can facilitate social interactions'.[3]

Гледишта

Some claim that humour should not be explained. Author E. B. White once said, "Humor can be dissected as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind."[4] Counter to this argument, protests against "offensive" cartoons invite the dissection of humour or its lack by aggrieved individuals and communities. This process of dissecting humour does not necessarily banish a sense of humour but directs attention towards its politics and assumed universality.[5]

Non-satirical humour can be specifically termed droll humour or recreational drollery.[6][7]

Порекло појма

У европске језике реч хумор је продрла с медицинском терминологијом. Наиме, средњи век и средњовековна ренесансна учења објашњавала су различите темпераменте, у духу Хипократове и Галенове традиције, као мешавину основних особина „елемената” и главних „хумора” у телу: крви, жучи, слузи и црне жучи. Нарушавање хармоније животних сокова и преовлађивање једног хумора сматрано је истовремено за предуслов болести и подлогу настраности. Одатле је реч хумор добила поред физиолошког и једно психолошко значење: добар, односно лош хумор означавао је човеково расположење. Повезивање појма хумор са комичним ефектима среће се у ренесансној комедији.

Историја

Хумор се појављује још у раној историји. У Светоме писму пророк Илија иронично саопштава идолопоклоницима бога Вала:

„А кад би у подне, стаде им се ругати Илија говорећи: вичите већма; јер је он бог! ваљда се нешто замислио, или је у послу, или на путу, или може бити да спава, да се пробуди.” (1 цар, 18, 27)

Врсте хумора (шала)

At school

The use of humour plays an important role in youth development.[8] Studies have shown that humour is especially important in social interactions with peers.[9] School entry is the time when the importance of parents fades into the background and social interaction with peers becomes increasingly important. Conflict is inherent in these interactions. The use of humour plays an important role in conflict resolution and ultimately in school success and psychological adjustment.[10][11] The use of humour that is socially acceptable leads to a lower likelihood of being a victim of bullying, whereas the use of self-disparaging humour leads to a higher likelihood of being bullied.[9] When students are bullied, the use of self-disparaging humour can lead to an exacerbation of the negative effects on the student's psychological adjustment to school.[9]

Studies

Laughter

One of the main focuses of modern psychological humour theory and research is to establish and clarify the correlation between humour and laughter. The major empirical findings here are that laughter and humour do not always have a one-to-one association. While most previous theories assumed the connection between the two almost to the point of them being synonymous, psychology has been able to scientifically and empirically investigate the supposed connection, its implications, and significance.

In 2009, Diana Szameitat conducted a study to examine the differentiation of emotions in laughter. They hired actors and told them to laugh with one of four different emotional associations by using auto-induction, where they would focus exclusively on the internal emotion and not on the expression of laughter itself. They found an overall recognition rate of 44%, with joy correctly classified at 44%, tickle 45%, schadenfreude 37%, and taunt 50%.[12]:399 Their second experiment tested the behavioural recognition of laughter during an induced emotional state and they found that different laughter types did differ with respect to emotional dimensions.[12]:401–402 In addition, the four emotional states displayed a full range of high and low sender arousal and valence.[12]:403 This study showed that laughter can be correlated with both positive (joy and tickle) and negative (schadenfreude and taunt) emotions with varying degrees of arousal in the subject.

Health

Adaptive Humour use has shown to be effective for increasing resilience in dealing with distress and also effective in buffering against or undoing negative affects. In contrast, maladaptive humour use can magnify potential negative effects.[9]

Madeljin Strick, Rob Holland, Rick van Baaren, and Ad van Knippenberg (2009) of Radboud University conducted a study that showed the distracting nature of a joke on bereaved individuals.[13]:574–578 Subjects were presented with a wide range of negative pictures and sentences. Their findings showed that humorous therapy attenuated the negative emotions elicited after negative pictures and sentences were presented. In addition, the humour therapy was more effective in reducing negative affect as the degree of affect increased in intensity.[13]:575–576 Humour was immediately effective in helping to deal with distress. The escapist nature of humour as a coping mechanism suggests that it is most useful in dealing with momentary stresses. Stronger negative stimuli requires a different therapeutic approach.

Studies, such as those testing the undoing hypothesis,[14]:313 have shown several positive outcomes of humour as an underlying positive trait in amusement and playfulness. Several studies have shown that positive emotions can restore autonomic quiescence after negative affect. For example, Frederickson and Levinson showed that individuals who expressed Duchenne smiles during the negative arousal of a sad and troubling event recovered from the negative affect approximately 20% faster than individuals who didn't smile.[14]:314

Using humour judiciously can have a positive influence on cancer treatment.[15] The effectiveness for humour‐based interventions in patients with schizophrenia is uncertain in a Cochrane review.[16]

Humour can serve as a strong distancing mechanism in coping with adversity. In 1997, Kelter and Bonanno found that Duchenne laughter correlated with reduced awareness of distress.[17] Positive emotion is able to loosen the grip of negative emotions on people’s thinking. A distancing of thought leads to a distancing of the unilateral responses people often have to negative arousal. In parallel with the distancing role plays in coping with distress, it supports the broaden and build theory that positive emotions lead to increased multilateral cognitive pathway and social resource building.

Види још

Референце

- ^ Raymond Smullyan, "The Planet Without Laughter", This Book Needs No Title

- ^ Peter McGraw, "Too close for Comfort, or Too Far to care? Finding Humor in Distant Tragedies and Close Mishaps"

- ^ Nicholas Kuiper, "Prudence and Racial Humor: Troubling Epithets"

- ^ „The Quotations Page: Quote from E.B. White”. Приступљено 26. 8. 2018.

- ^ Ritu Gairola Khanduri. 2014. Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History of the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Seth Benedict Graham A cultural analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot 2003 p. 13

- ^ Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World [1941, 1965]. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press p. 12

- ^ Legkauskas, V., Magelinskaitė-Legkauskienė, Š. (2021). „Social competence in the 1st grade predicts school adjustment two years later”. Early Child Development and Care. 191 (1): 83—92. ISSN 0300-4430. S2CID 150567697. doi:10.1080/03004430.2019.1603149.

- ^ а б в г Burger, C. (2022). „Humor styles, bullying victimization and psychological school adjustment: Mediation, moderation and person-oriented analyses”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (18): 11415. ISSN 1661-7827. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811415

.

.

- ^ Kiuru, N., Wang, M.-T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., Hirvonen, R. (2020). „Associations between adolescents' interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions”. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 49 (5): 1057—1072. ISSN 0047-2891. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-01184-y.

- ^ Søndergaard, D. M. (2018). „The thrill of bullying. Bullying, humour and the making of community”. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 48 (1): 48—65. ISSN 0021-8308. doi:10.1111/jtsb.12153.

- ^ а б в Szameitat, Diana P., et al. Differentiation of Emotions in Laughter at the Behavioural Level. 2009 Emotion 9 (3).

- ^ а б Strick, Madelijn; et al. (2009). „Finding Comfort in a Joke: Consolatory Effects of Humor Through Cognitive Distraction”. Emotion. 9 (4): 574—578. PMID 19653782. S2CID 14369631. doi:10.1037/a0015951.

- ^ а б Fredrickson, Barbara L. (1998). „What Good Are Positive Emotions?”. Review of General Psychology. 2 (3): 300—319. PMC 3156001

. PMID 21850154. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300.

. PMID 21850154. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300.

- ^ „Humor in Cancer Treatment”. Приступљено 22. 1. 2017.

- ^ Tsujimoto, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; et al. (2021). „Humour‐based interventions for people with schizophrenia”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (10): CD013367. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013367.pub2.

- ^ Keltner, D.; Bonanno, G. A. (1997). „A study of laughter and dissociation: Distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 73 (4): 687—702. PMID 9325589. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.687.

Лиратура

- Alexander, Richard (1984), Verbal humor and variation in English: Sociolinguistic notes on a variety of jokes

- Alexander, Richard (1997), Aspects of verbal humour in English

- Basu, S (децембар 1999), „Dialogic ethics and the virtue of humor”, Journal of Political Philosophy, 7 (4): 378—403, doi:10.1111/1467-9760.00082, Приступљено 2007-07-06 (Abstract)

- Billig, M. (2005). Laughter and ridicule: Towards a social critique of humour. London: Sage. ISBN 1-4129-1143-5

- Bricker, Victoria Reifler (Winter, 1980) The Function of Humor in Zinacantan Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 411–418

- Buijzen, Moniek; Valkenburg, Patti M. (2004), „Developing a Typology of Humor in Audiovisual Media”, Media Psychology, 6 (2): 147—167, S2CID 96438940, doi:10.1207/s1532785xmep0602_2(Abstract)

- Carrell, Amy (2000), Historical views of humour, University of Central Oklahoma. Retrieved on 2007-07-06.

- García-Barriocanal, Elena; Sicilia, Miguel-Angel; Palomar, David (2005), A Graphical Humor Ontology for Contemporary Cultural Heritage Access (PDF), Madrid: University of Alcalá, Архивирано из оригинала (PDF) 2006-05-23. г., Приступљено 2007-07-06

- Goldstein, Jeffrey H., et al. (1976) "Humour, Laughter, and Comedy: A Bibliography of Empirical and Nonempirical Analyses in the English Language." It's a Funny Thing, Humour. Ed. Antony J. Chapman and Hugh C. Foot. Oxford and New York: Pergamon Press, 1976. 469–504.

- Hurley, Matthew M., Dennett, Daniel C., and Adams, Reginald B. Jr. (2011), Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01582-0

- Holland, Norman. (1982) "Bibliography of Theories of Humor." Laughing; A Psychology of Humor. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 209–223.

- Martin, Rod A. (2007). The Psychology Of Humour: An Integrative Approach. London, UK: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-372564-6

- McGhee, Paul E. (1984) "Current American Psychological Research on Humor." Jahrbuche fur Internationale Germanistik 16.2: 37–57.

- Mintz, Lawrence E., ed. (1988) Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1988. ISBN 0-313-24551-7; OCLC 16085479.

- Mobbs, D.; Greicius, M. D.; Abdel-Azim, E.; Menon, V.; Reiss, A. L. (2003), „Humor modulates the mesolimbic reward centres”, Neuron, 40 (5): 1041—1048, PMID 14659102, doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00751-7

.

. - Nilsen, Don L. F. (1992) "Satire in American Literature." Humor in American Literature: A Selected Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland, 1992. 543–48.

- Pogel, Nancy; and Paul P. Somers Jr. (1988) "Literary Humor." Humor in America: A Research Guide to Genres and Topics. Ed. Lawrence E. Mintz. London: Greenwood, 1988. 1–34.

- Roth, G.; Yap, R.; Short, D. (2006). „Examining humour in HRD from theoretical and practical perspectives”. Human Resource Development International. 9 (1): 121—127. S2CID 143854518. doi:10.1080/13678860600563424.

- Smuts, Aaron. "Humor". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Wogan, Peter (пролеће 2006), „Laughing At First Contact”, Visual Anthropology Review (објављено 12. 12. 2006), 22 (1): 14—34, doi:10.1525/var.2006.22.1.14

- Wild, B., Rodden, F.A., Grodd, W., & Ruch, W. (2003). Neural correlates of laughter and humour. Brain, 126, 2121-1238.

- Goel, V., & Dolan, R. (2001). The functional anatomy of humor: Segregating cognitive and affective components. Nature Neuroscience, 4(3), 237-8.

- Gervais, M. & Wilson, D., 2005. The evolution and functions of laughter and humor: A synthetic approach. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 80(4), 395-430

- Spoor, J. R. & Kelly, J. R. (2004). The evolutionary significance of affect in groups: Communication and group bonding. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 7, 398-412

- Neuhoff, C. & Shaeffer, C. (2002). Effects of laughing, smiling, and howling on mood. Psychological Reports, 91, 1079-1080

- Burger, C. (2022). „Humor styles, bullying victimization and psychological school adjustment: Mediation, moderation and person-oriented analyses”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (18): 11415. ISSN 1661-7827. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811415

.

. - Robinson, L. (2020, October). Laughter is the Best Medicine. https://www.helpguide.org/articles/mental-health/laughter-is-the-best-medicine.htm Архивирано 2022-02-18 на сајту Wayback Machine

- Henry Ford Health System Staff. How Laughter Benefits Your Heart Health. https://www.henryford.com/blog/2019/03/how-laughter-benefits-heart-health#:~:text=Reduces%20blood%20pressure.,takes%20tension%20off%20your%20heart Архивирано 2021-10-06 на сајту Wayback Machine

Спољашње везе

- Humor на сајту Curlie (језик: енглески)

- International Society for Humor Studies