Закон великих бројева — разлика између измена

м Бот: по захтеву Садка |

. ознака: везе до вишезначних одредница |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

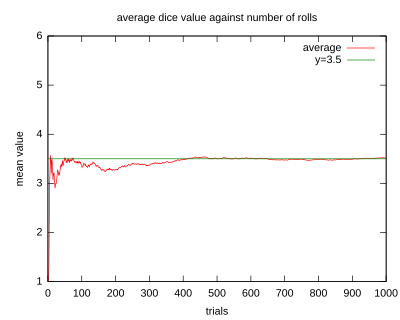

[[Датотека:Largenumbers.svg|мини|десно|400п|Илустрација закона великих бројева на примеру бацања коцке. Ако се број бацања повећава, просечна вредност исхода се приближава вредности 3,5.]] |

[[Датотека:Largenumbers.svg|мини|десно|400п|Илустрација закона великих бројева на примеру бацања коцке. Ако се број бацања повећава, просечна вредност исхода се приближава вредности 3,5.]] |

||

| ⚫ | [[Датотека:DiffusionMicroMacro.gif|thumb|right|250px|[[Molecular diffusion|Дифузија]] је пример закона великих бројева. У почетку, на левој страни баријере налазе се молекули [[раствор|растворених]] материја (магентна линија) и ни један на десној страни. Преграда се уклања, и раствор се дифундира да попуни цео контејнер.<br> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | <u>Доле:</u> Са огромним бројем молекула растворене супстанце (превише да се могу видети), случајност је у суштини нестала: Чини се да растворак иде глатко и систематски од подручја високе концентрације до подручја са ниском концентрацијом. У реалним ситуацијама, хемичари могу описати дифузију као детерминистички макроскопски феномен (погледајте [[Fick's law|Фикове законе]]), упркос њене радомне природе.]] |

||

| ⚫ | '''Закон великих бројева''' (LLN) је фундаментална [[теорема]] из области [[Теорија вероватноће|теорије вероватноће]] и [[Статистика|статистике]]. У своме најједноставнијем облику овај закон тврди да се релативна вероватноћа [[Случајан догађај|случајног догађаја]] приближава вероватноћи овог догађаја када се случајни експеримент понавља велики број пута. Формалније, ради се о [[Конвергенција|конвергенцији]] [[Случајна променљива|случајне променљиве]] у „јаком“ (скоро сигурна конвергенција) и „слабом“ смислу (конвергенција вероватноће).<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics| url=https://archive.org/details/modernintroducti00fmde|url-access=limited| last=Dekking|first=Michel| publisher=Springer| year=2005|isbn=9781852338961|pages=[https://archive.org/details/modernintroducti00fmde/page/n191 181]–190}}</ref> |

||

'''Закон великих бројева''' је фундаментална [[теорема]] из области [[Теорија вероватноће|теорије вероватноће]] и [[Статистика|статистике]]. |

|||

{{рут}} |

|||

The LLN is important because it guarantees stable long-term results for the averages of some random events.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Yao|first1=Kai|last2=Gao|first2=Jinwu|date=2016|title=Law of Large Numbers for Uncertain Random Variables|journal=IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems| volume=24| issue=3| pages=615–621| doi=10.1109/TFUZZ.2015.2466080| s2cid=2238905|issn=1063-6706}}</ref> For example, while a [[casino]] may lose money in a single spin of the [[roulette]] wheel, its earnings will tend towards a predictable percentage over a large number of spins. Any winning streak by a player will eventually be overcome by the parameters of the game. Importantly, the law applies (as the name indicates) only when a ''large number'' of observations are considered. There is no principle that a small number of observations will coincide with the expected value or that a streak of one value will immediately be "balanced" by the others (see the [[gambler's fallacy]]). |

|||

The LLN only applies to the average. Therefore, while |

|||

| ⚫ | У своме најједноставнијем облику овај закон тврди да се релативна вероватноћа [[Случајан догађај|случајног догађаја]] приближава вероватноћи овог догађаја када се случајни експеримент понавља велики број пута. Формалније, ради се о [[Конвергенција|конвергенцији]] [[Случајна променљива|случајне променљиве]] у „јаком“ (скоро сигурна конвергенција) и „слабом“ смислу (конвергенција вероватноће). |

||

<math display="block">\lim_{n\to\infty} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{X_i} n = \overline{X}</math> |

|||

other formulas that look similar are not verified, such as the raw deviation from "theoretical results": |

|||

<math display="block">\sum_{i=1}^n X_i - n\times\overline{X}</math> |

|||

not only does it not converge toward zero as ''n'' increases, but it tends to increase in absolute value as ''n'' increases. |

|||

== Пример: бацање новчића == |

== Пример: бацање новчића == |

||

| Ред 20: | Ред 26: | ||

* Медицина: Када се проучава ефикасност медицинских третмана, помоћу овог закона се могу елиминистаи случајни споредни фактори. |

* Медицина: Када се проучава ефикасност медицинских третмана, помоћу овог закона се могу елиминистаи случајни споредни фактори. |

||

* Природне науке: Утицај несистематских грешки у мерењу се смањује понављањем мерења. |

* Природне науке: Утицај несистематских грешки у мерењу се смањује понављањем мерења. |

||

* Информатика: Постоје информатичке технике код којих се примењује овај закон. Пример је [[ |

* Информатика: Постоје информатичке технике код којих се примењује овај закон. Пример је [[рачунарство у облаку]]. |

||

== Ограничење == |

|||

The average of the results obtained from a large number of trials may fail to converge in some cases. For instance, the average of ''n'' results taken from the [[Cauchy distribution]] or some [[Pareto distribution]]s (α<1) will not converge as ''n'' becomes larger; the reason is [[Heavy-tailed distribution|heavy tails]]. The Cauchy distribution and the Pareto distribution represent two cases: the Cauchy distribution does not have an expectation,<ref>{{Cite book|title=A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics|url=https://archive.org/details/modernintroducti00fmde|url-access=limited| last=Dekking|first=Michel|publisher=Springer|year=2005|isbn=9781852338961|pages=[https://archive.org/details/modernintroducti00fmde/page/n102 92]}}</ref> whereas the expectation of the Pareto distribution (''α''<1) is infinite.<ref>{{Cite book|title=A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics|url=https://archive.org/details/modernintroducti00fmde| url-access=limited| last=Dekking|first=Michel| publisher=Springer| year=2005| isbn=9781852338961| pages=[https://archive.org/details/modernintroducti00fmde/page/n74 63]}}</ref> One way to generate the Cauchy-distributed example is where the random numbers equal the [[tangent]] of an angle uniformly distributed between −90° and +90°. The [[median]] is zero, but the expected value does not exist, and indeed the average of ''n'' such variables have the same distribution as one such variable. It does not converge in probability toward zero (or any other value) as ''n'' goes to infinity. |

|||

And if the trials embed a selection bias, typical in human economic/rational behaviour, the law of large numbers does not help in solving the bias. Even if the number of trials is increased the selection bias remains. |

|||

== Историја == |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Датотека:DiffusionMicroMacro.gif|thumb|right|250px|[[Molecular diffusion|Дифузија]] је пример закона великих бројева. У почетку, на левој страни баријере налазе се молекули [[раствор|растворених]] материја (магентна линија) и ни један на десној страни. Преграда се уклања, и раствор се дифундира да попуни цео контејнер.<br> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | <u>Доле:</u> Са огромним бројем молекула растворене супстанце (превише да се могу видети), случајност је у суштини нестала: Чини се да растворак иде глатко и систематски од подручја високе концентрације до подручја са ниском концентрацијом. У реалним ситуацијама, хемичари могу описати дифузију као детерминистички макроскопски феномен (погледајте [[Fick's law|Фикове законе]]), упркос њене радомне природе.]] |

||

The Italian mathematician [[Gerolamo Cardano]] (1501–1576) stated without proof that the accuracies of empirical statistics tend to improve with the number of trials.<ref>{{cite book |last=Mlodinow |first=L. |title=The Drunkard's Walk |location=New York |publisher=Random House |year=2008 |page=50}}</ref> This was then formalized as a law of large numbers. A special form of the LLN (for a binary random variable) was first proved by [[Jacob Bernoulli]].<ref>{{cite book |first=Jakob |last=Bernoulli |title=Ars Conjectandi: Usum & Applicationem Praecedentis Doctrinae in Civilibus, Moralibus & Oeconomicis |language=la |year=1713 |chapter=4 |translator-first=Oscar |translator-last=Sheynin}}</ref> It took him over 20 years to develop a sufficiently rigorous mathematical proof which was published in his {{lang|la|italic=yes|[[Ars Conjectandi]]}} (''The Art of Conjecturing'') in 1713. He named this his "Golden Theorem" but it became generally known as "'''Bernoulli's theorem'''". This should not be confused with [[Bernoulli's principle]], named after Jacob Bernoulli's nephew [[Daniel Bernoulli]]. In 1837, [[Siméon Denis Poisson|S. D. Poisson]] further described it under the name {{lang|fr|"la loi des grands nombres"}} ("the law of large numbers").<ref>Poisson names the "law of large numbers" ({{lang|fr|la loi des grands nombres}}) in: {{cite book |first=S. D. |last=Poisson |title=Probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et en matière civile, précédées des règles générales du calcul des probabilitiés |location=Paris, France |publisher=Bachelier |year=1837 |page=[https://archive.org/details/recherchessurla02poisgoog/page/n30 7] |language=fr}} He attempts a two-part proof of the law on pp. 139–143 and pp. 277 ff.</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Hacking |first=Ian |year=1983 |title=19th-century Cracks in the Concept of Determinism |journal=Journal of the History of Ideas |volume=44 |issue=3 |pages=455–475 |doi=10.2307/2709176 |jstor=2709176}}</ref> Thereafter, it was known under both names, but the "law of large numbers" is most frequently used. |

|||

After Bernoulli and Poisson published their efforts, other mathematicians also contributed to refinement of the law, including [[Pafnuty Chebyshev|Chebyshev]],<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Tchebichef | first1 = P. | title = Démonstration élémentaire d'une proposition générale de la théorie des probabilités | doi = 10.1515/crll.1846.33.259 | journal = Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik | volume = 1846 | issue = 33 | pages = 259–267 | year = 1846 | s2cid = 120850863 | url = https://zenodo.org/record/1448850 |language=fr}}</ref> [[Andrey Markov|Markov]], [[Émile Borel|Borel]], [[Francesco Paolo Cantelli|Cantelli]], [[Andrey Kolmogorov|Kolmogorov]] and [[Aleksandr Khinchin|Khinchin]]. Markov showed that the law can apply to a random variable that does not have a finite variance under some other weaker assumption, and Khinchin showed in 1929 that if the series consists of independent identically distributed random variables, it suffices that the [[expected value]] exists for the weak law of large numbers to be true.{{sfn|Seneta|2013}}<ref name=EncMath>{{cite web| author1=Yuri Prohorov|author-link1=Yuri Vasilyevich Prokhorov|title=Law of large numbers| url=https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php/Law_of_large_numbers| website=Encyclopedia of Mathematics |publisher=EMS Press}}</ref> These further studies have given rise to two prominent forms of the LLN. One is called the "weak" law and the other the "strong" law, in reference to two different modes of [[limit of a sequence|convergence]] of the cumulative sample means to the expected value; in particular, as explained below, the strong form implies the weak.{{sfn|Seneta|2013}} |

|||

== Форме == |

|||

There are two different versions of the '''law of large numbers''' that are described below. They are called the'' '''strong law''' of large numbers'' and the '''''weak law''' of large numbers''.<ref>{{Cite book|title=A Course in Mathematical Statistics and Large Sample Theory| last1=Bhattacharya|first1=Rabi| last2=Lin|first2=Lizhen| last3=Patrangenaru|first3=Victor| date=2016| publisher=Springer New York| isbn=978-1-4939-4030-1| series=Springer Texts in Statistics| location=New York, NY| doi=10.1007/978-1-4939-4032-5}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> Stated for the case where ''X''<sub>1</sub>, ''X''<sub>2</sub>, ... is an infinite sequence of [[Independent and identically distributed random variables|independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.)]] [[Lebesgue integration|Lebesgue integrable]] random variables with expected value E(''X''<sub>1</sub>) = E(''X''<sub>2</sub>) = ... = ''µ'', both versions of the law state that the sample average |

|||

<math display="block">\overline{X}_n=\frac1n(X_1+\cdots+X_n) </math> |

|||

converges to the expected value: |

|||

{{NumBlk||<math display="block">\overline{X}_n \to \mu \quad\textrm{as}\ n \to \infty.</math>|{{EquationRef|1}}}} |

|||

(Lebesgue integrability of ''X<sub>j</sub>'' means that the expected value E(''X<sub>j</sub>'') exists according to Lebesgue integration and is finite. It does ''not'' mean that the associated probability measure is [[absolutely continuous]] with respect to [[Lebesgue measure]].) |

|||

Introductory probability texts often additionally assume identical finite [[variance]] <math> \operatorname{Var} (X_i) = \sigma^2 </math> (for all <math>i</math>) and no correlation between random variables. In that case, the variance of the average of n random variables is |

|||

<math display="block">\operatorname{Var}(\overline{X}_n) = \operatorname{Var}(\tfrac1n(X_1+\cdots+X_n)) = \frac{1}{n^2} \operatorname{Var}(X_1+\cdots+X_n) = \frac{n\sigma^2}{n^2} = \frac{\sigma^2}{n}.</math> |

|||

which can be used to shorten and simplify the proofs. This assumption of finite [[variance]] is ''not necessary''. Large or infinite variance will make the convergence slower, but the LLN holds anyway.<ref name="TaoBlog">{{cite web|title=The strong law of large numbers – What's new|date=19 June 2008|url=http://terrytao.wordpress.com/2008/06/18/the-strong-law-of-large-numbers/|access-date=2012-06-09|publisher=Terrytao.wordpress.com}}</ref> |

|||

[[Independence (probability theory)#More than two random variables|Mutual independence]] of the random variables can be replaced by [[pairwise independence]]<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Etemadi|first1=N. Z.|date=1981|title=An elementary proof of the strong law of large numbers|journal=Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie Verw Gebiete| volume=55| issue=1| pages=119–122| doi=10.1007/BF01013465|s2cid=122166046}}</ref> or [[Exchangeable random variables|exchangeability]]<ref>{{Cite journal| last=Kingman|first=J. F. C.|date=April 1978|title=Uses of Exchangeability|url=https://projecteuclid.org/journals/annals-of-probability/volume-6/issue-2/Uses-of-Exchangeability/10.1214/aop/1176995566.full|journal=The Annals of Probability| language=en| volume=6|issue=2|doi=10.1214/aop/1176995566|issn=0091-1798|doi-access=free}}</ref> in both versions of the law. |

|||

The difference between the strong and the weak version is concerned with the mode of convergence being asserted. For interpretation of these modes, see [[Convergence of random variables]]. |

|||

== Слаби закон великих бројева == |

=== Слаби закон великих бројева === |

||

За низ случајних променљивих <math>X_1, X_2, X_3, \dots</math> у <math>\mathcal{L}^1</math> каже се да задовољава ''слаби закон великих бројева'', када за <math>\overline{X}_n=\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_i-E ({X}_i))/n</math> и све позитивне бројеве <math>\varepsilon</math> важи: |

За низ случајних променљивих <math>X_1, X_2, X_3, \dots</math> у <math>\mathcal{L}^1</math> каже се да задовољава ''слаби закон великих бројева'', када за <math>\overline{X}_n=\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_i-E ({X}_i))/n</math> и све позитивне бројеве <math>\varepsilon</math> важи: |

||

| Ред 31: | Ред 72: | ||

[[варијанса|варијансе]] <math>\sigma_1^2, \sigma_2^2, \sigma_3^2\dots</math>, које су ограничене заједничком горњом границом, и нису међусобно [[Корелација|корелисане]]: <math>\operatorname{Cov}(X_i, X_j) = 0</math> за <math>i\neq j</math>.<ref>H.-O. Georgii: ''Stochastik'', 2. Auflage, de Gruyter, 2004, S. 120 Satz (5.6) Schwaches Gesetz der großen Zahlen, <math>\mathcal L^2</math>-Version.</ref> |

[[варијанса|варијансе]] <math>\sigma_1^2, \sigma_2^2, \sigma_3^2\dots</math>, које су ограничене заједничком горњом границом, и нису међусобно [[Корелација|корелисане]]: <math>\operatorname{Cov}(X_i, X_j) = 0</math> за <math>i\neq j</math>.<ref>H.-O. Georgii: ''Stochastik'', 2. Auflage, de Gruyter, 2004, S. 120 Satz (5.6) Schwaches Gesetz der großen Zahlen, <math>\mathcal L^2</math>-Version.</ref> |

||

== Јаки закон великих бројева == |

=== Јаки закон великих бројева === |

||

Каже се да низ случајних променљивих <math>X_1, X_2, X_3, \dots</math> у <math>\mathcal{L}^1</math> задовољава ''јаки закон великих бројева'', када за <math>\overline{X}_n=\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_i-E ({X}_i))/n</math> важи: |

Каже се да низ случајних променљивих <math>X_1, X_2, X_3, \dots</math> у <math>\mathcal{L}^1</math> задовољава ''јаки закон великих бројева'', када за <math>\overline{X}_n=\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_i-E ({X}_i))/n</math> важи: |

||

Верзија на датум 26. јун 2023. у 10:38

Закон великих бројева (LLN) је фундаментална теорема из области теорије вероватноће и статистике. У своме најједноставнијем облику овај закон тврди да се релативна вероватноћа случајног догађаја приближава вероватноћи овог догађаја када се случајни експеримент понавља велики број пута. Формалније, ради се о конвергенцији случајне променљиве у „јаком“ (скоро сигурна конвергенција) и „слабом“ смислу (конвергенција вероватноће).[1]

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

The LLN is important because it guarantees stable long-term results for the averages of some random events.[1][2] For example, while a casino may lose money in a single spin of the roulette wheel, its earnings will tend towards a predictable percentage over a large number of spins. Any winning streak by a player will eventually be overcome by the parameters of the game. Importantly, the law applies (as the name indicates) only when a large number of observations are considered. There is no principle that a small number of observations will coincide with the expected value or that a streak of one value will immediately be "balanced" by the others (see the gambler's fallacy).

The LLN only applies to the average. Therefore, while

other formulas that look similar are not verified, such as the raw deviation from "theoretical results":

not only does it not converge toward zero as n increases, but it tends to increase in absolute value as n increases.

Пример: бацање новчића

Вероватноћа да бачени новчић покаже писмо или главу износи ½. Што се више понавља овај експеримент, то ће бити вероватније да ће број исхода када „падне глава“ (релативна вероватноћа исхода „глава“), бити близак вредности ½. Са друге стране, врло је вероватно да ће апсолутна разлика између броја исхода „глава“ и половине броја бацања новчића расти.

Постоји и укорењено погрешно схватање закона великих бројева. Овај закон не тврди да ће они исходи који се до сада нису појављивали, од сада појављивати чешће да би уравнотежили расподелу вероватноћа. То је честа грешка играча рулета и лотоа.

Нека је низ исхода бацања новчића: глава, грб, глава, глава. Исход „глава“ се појавио три пута, а исход „грб“ једанпут. „Глава“ се дакле појављивала са релативним учешћем ¾, док је ова вредност за „грб“ ¼. После нових 96 бацања новчића исход је био 49 „грбова“ и 51 „глава“. Апсолутна разлика глава и грбова је после 100 бацања остала иста и као после 4, али је релативна разлика знатно смањена. Тако долазимо до дефиниције Закона великих бројева – вредност релативног учешћа тежи очекиваној вредности 0,5.

Практичне импликације

- Индустрија осигурања: Закон великих бројева има велики практични значај за индустрију осигурања. Он омогућава да се направе дугорочне прогнозе износа одштетних захтева. Што је већи број осигураних особа и добара, и ако се подразумева да су сви изложени једнаком ризику, то је мањи утицај случаја. Овај закон, ипак, не може да да никакву прогнозу о томе ко ће конкретно уложити одштетни захтев.

- Медицина: Када се проучава ефикасност медицинских третмана, помоћу овог закона се могу елиминистаи случајни споредни фактори.

- Природне науке: Утицај несистематских грешки у мерењу се смањује понављањем мерења.

- Информатика: Постоје информатичке технике код којих се примењује овај закон. Пример је рачунарство у облаку.

Ограничење

The average of the results obtained from a large number of trials may fail to converge in some cases. For instance, the average of n results taken from the Cauchy distribution or some Pareto distributions (α<1) will not converge as n becomes larger; the reason is heavy tails. The Cauchy distribution and the Pareto distribution represent two cases: the Cauchy distribution does not have an expectation,[3] whereas the expectation of the Pareto distribution (α<1) is infinite.[4] One way to generate the Cauchy-distributed example is where the random numbers equal the tangent of an angle uniformly distributed between −90° and +90°. The median is zero, but the expected value does not exist, and indeed the average of n such variables have the same distribution as one such variable. It does not converge in probability toward zero (or any other value) as n goes to infinity.

And if the trials embed a selection bias, typical in human economic/rational behaviour, the law of large numbers does not help in solving the bias. Even if the number of trials is increased the selection bias remains.

Историја

Горе: Са једним молекулом, кретање изгледа сасвим случајно.

Средина: Са више молекула, јасно је присутан тренд где растворена материја све више и више униформно испуњава контејнер, али постоје и случајне флуктуације.

Доле: Са огромним бројем молекула растворене супстанце (превише да се могу видети), случајност је у суштини нестала: Чини се да растворак иде глатко и систематски од подручја високе концентрације до подручја са ниском концентрацијом. У реалним ситуацијама, хемичари могу описати дифузију као детерминистички макроскопски феномен (погледајте Фикове законе), упркос њене радомне природе.

The Italian mathematician Gerolamo Cardano (1501–1576) stated without proof that the accuracies of empirical statistics tend to improve with the number of trials.[5] This was then formalized as a law of large numbers. A special form of the LLN (for a binary random variable) was first proved by Jacob Bernoulli.[6] It took him over 20 years to develop a sufficiently rigorous mathematical proof which was published in his Ars Conjectandi (The Art of Conjecturing) in 1713. He named this his "Golden Theorem" but it became generally known as "Bernoulli's theorem". This should not be confused with Bernoulli's principle, named after Jacob Bernoulli's nephew Daniel Bernoulli. In 1837, S. D. Poisson further described it under the name "la loi des grands nombres" ("the law of large numbers").[7][8] Thereafter, it was known under both names, but the "law of large numbers" is most frequently used.

After Bernoulli and Poisson published their efforts, other mathematicians also contributed to refinement of the law, including Chebyshev,[9] Markov, Borel, Cantelli, Kolmogorov and Khinchin. Markov showed that the law can apply to a random variable that does not have a finite variance under some other weaker assumption, and Khinchin showed in 1929 that if the series consists of independent identically distributed random variables, it suffices that the expected value exists for the weak law of large numbers to be true.[10][11] These further studies have given rise to two prominent forms of the LLN. One is called the "weak" law and the other the "strong" law, in reference to two different modes of convergence of the cumulative sample means to the expected value; in particular, as explained below, the strong form implies the weak.[10]

Форме

There are two different versions of the law of large numbers that are described below. They are called the strong law of large numbers and the weak law of large numbers.[12][1] Stated for the case where X1, X2, ... is an infinite sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) Lebesgue integrable random variables with expected value E(X1) = E(X2) = ... = µ, both versions of the law state that the sample average

converges to the expected value:

|

(1) |

(Lebesgue integrability of Xj means that the expected value E(Xj) exists according to Lebesgue integration and is finite. It does not mean that the associated probability measure is absolutely continuous with respect to Lebesgue measure.)

Introductory probability texts often additionally assume identical finite variance (for all ) and no correlation between random variables. In that case, the variance of the average of n random variables is

which can be used to shorten and simplify the proofs. This assumption of finite variance is not necessary. Large or infinite variance will make the convergence slower, but the LLN holds anyway.[13]

Mutual independence of the random variables can be replaced by pairwise independence[14] or exchangeability[15] in both versions of the law.

The difference between the strong and the weak version is concerned with the mode of convergence being asserted. For interpretation of these modes, see Convergence of random variables.

Слаби закон великих бројева

За низ случајних променљивих у каже се да задовољава слаби закон великих бројева, када за и све позитивне бројеве важи:

- .

Постоји мноштво ситуација у којима се може применити Слаби закон великих бројева. На пример, он важи за низ случајних променљивих које имају коначне варијансе , које су ограничене заједничком горњом границом, и нису међусобно корелисане: за .[16]

Јаки закон великих бројева

Каже се да низ случајних променљивих у задовољава јаки закон великих бројева, када за важи:

- .

Јаки закон великих бројева имплицира слаби закон великих бројева. Јаки закон великих бројева важи за, на пример, низ стохастички независних случајних променљивих које имају једнаку расподелу вероватноће. Један облик овог закона за независне случајне променљиве је ергодичност.

Види још

Референце

- ^ а б в Dekking, Michel (2005). A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics

. Springer. стр. 181–190. ISBN 9781852338961.

. Springer. стр. 181–190. ISBN 9781852338961.

- ^ Yao, Kai; Gao, Jinwu (2016). „Law of Large Numbers for Uncertain Random Variables”. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems. 24 (3): 615—621. ISSN 1063-6706. S2CID 2238905. doi:10.1109/TFUZZ.2015.2466080.

- ^ Dekking, Michel (2005). A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics

. Springer. стр. 92. ISBN 9781852338961.

. Springer. стр. 92. ISBN 9781852338961.

- ^ Dekking, Michel (2005). A Modern Introduction to Probability and Statistics

. Springer. стр. 63. ISBN 9781852338961.

. Springer. стр. 63. ISBN 9781852338961.

- ^ Mlodinow, L. (2008). The Drunkard's Walk. New York: Random House. стр. 50.

- ^ Bernoulli, Jakob (1713). „4”. Ars Conjectandi: Usum & Applicationem Praecedentis Doctrinae in Civilibus, Moralibus & Oeconomicis (на језику: латински). Превод: Sheynin, Oscar.

- ^ Poisson names the "law of large numbers" (la loi des grands nombres) in: Poisson, S. D. (1837). Probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et en matière civile, précédées des règles générales du calcul des probabilitiés (на језику: француски). Paris, France: Bachelier. стр. 7. He attempts a two-part proof of the law on pp. 139–143 and pp. 277 ff.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (1983). „19th-century Cracks in the Concept of Determinism”. Journal of the History of Ideas. 44 (3): 455—475. JSTOR 2709176. doi:10.2307/2709176.

- ^ Tchebichef, P. (1846). „Démonstration élémentaire d'une proposition générale de la théorie des probabilités”. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (на језику: француски). 1846 (33): 259—267. S2CID 120850863. doi:10.1515/crll.1846.33.259.

- ^ а б Seneta 2013.

- ^ Yuri Prohorov. „Law of large numbers”. Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Rabi; Lin, Lizhen; Patrangenaru, Victor (2016). A Course in Mathematical Statistics and Large Sample Theory. Springer Texts in Statistics. New York, NY: Springer New York. ISBN 978-1-4939-4030-1. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-4032-5.

- ^ „The strong law of large numbers – What's new”. Terrytao.wordpress.com. 19. 6. 2008. Приступљено 2012-06-09.

- ^ Etemadi, N. Z. (1981). „An elementary proof of the strong law of large numbers”. Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie Verw Gebiete. 55 (1): 119—122. S2CID 122166046. doi:10.1007/BF01013465.

- ^ Kingman, J. F. C. (април 1978). „Uses of Exchangeability”. The Annals of Probability (на језику: енглески). 6 (2). ISSN 0091-1798. doi:10.1214/aop/1176995566

.

.

- ^ H.-O. Georgii: Stochastik, 2. Auflage, de Gruyter, 2004, S. 120 Satz (5.6) Schwaches Gesetz der großen Zahlen, -Version.

Литература

- Grimmett, G. R.; Stirzaker, D. R. (1992). Probability and Random Processes, 2nd Edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-853665-8.

- Richard Durrett (1995). Probability: Theory and Examples, 2nd Edition. Duxbury Press.

- Martin Jacobsen (1992). Videregående Sandsynlighedsregning (Advanced Probability Theory) 3rd Edition. HCØ-tryk, Copenhagen. ISBN 87-91180-71-6.

- Loève, Michel (1977). Probability theory 1 (4th изд.). Springer Verlag.

- Newey, Whitney K.; McFadden, Daniel (1994). Large sample estimation and hypothesis testing. Handbook of econometrics, vol. IV, Ch. 36. Elsevier Science. стр. 2111—2245.

- Ross, Sheldon (2009). A first course in probability (8th изд.). Prentice Hall press. ISBN 978-0-13-603313-4.

- Sen, P. K; Singer, J. M. (1993). Large sample methods in statistics. Chapman & Hall, Inc.

- Seneta, Eugene (2013), „A Tricentenary history of the Law of Large Numbers”, Bernoulli, 19 (4): 1088—1121, arXiv:1309.6488

, doi:10.3150/12-BEJSP12

, doi:10.3150/12-BEJSP12

Спољашње везе

- Hazewinkel Michiel, ур. (2001). „Law of large numbers”. Encyclopaedia of Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 978-1556080104.

- Weisstein, Eric W. „Weak Law of Large Numbers”. MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. „Strong Law of Large Numbers”. MathWorld.

- Animations for the Law of Large Numbers by Yihui Xie using the R package animation

- Apple CEO Tim Cook said something that would make statisticians cringe.