Снег — разлика између измена

м Враћене измене 178.223.66.20 (разговор) на последњу измену корисника Ранко Николић |

. |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{друго значење3| |

{{друго значење3|Снег (филм)}} |

||

{{Infobox material |

|||

{{bez_izvora}} |

|||

| name = Снег |

|||

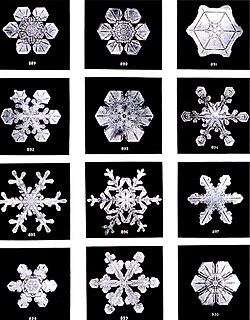

[[Датотека:SnowflakesWilsonBentley.jpg|мини|200п|Пахуљице (Вилсон Бентли, 1902.)]] |

|||

| image = CargoNet Di 12 Euro 4000 Lønsdal - Bolna.jpg |

|||

'''Снијег''' (или '''снег''') је [[падавине|падавина]] у облику ледених [[кристал]]а [[вода|воде]], која се састоји од мноштва пахуљица. Иако се састоји од малих, неправилних дијелова, снијег је у ствари зрнасти материјал. Има отворену и меку структуру, док се не нађе под спољашњим притиском. |

|||

| image_size = 250px |

|||

| alt = |

|||

| caption = Норвешки воз пролази кроз снег |

|||

| type = |

|||

| density = 0,1 – 0,8 -{g/cm}-<sup>3</sup> |

|||

| radiation_resistance = |

|||

| uv_resistance = |

|||

| youngs_modulus = |

|||

| tensile_strength = 1,5 – 3,5 -{kPa}-<ref name = Snowenclyclopedia/> |

|||

| elongation = |

|||

| compressive_strength = 3 – 7 -{MPa}-<ref name = Snowenclyclopedia/> |

|||

| poissons_ratio = |

|||

| coeff_friction = |

|||

| melting_point = 0 °-{C}- |

|||

| heat_transfer_coeff = |

|||

| thermal_conductivity_note = За густине 0,1 до 0,5 -{g/cm}-<sup>3</sup> |

|||

| thermal_conductivity = 0,05 – 0,7 -{W K}-<sup>−1</sup> m<sup>−1</sup> |

|||

| thermal_diffusivity_note = |

|||

| thermal_diffusivity = |

|||

| linear_expansion = |

|||

| specific_heat = |

|||

| dielectric_constant_note = За суви снег густине 0,1 од 0,9 -{g/cm}-<sup>3</sup> |

|||

| dielectric_constant = 1 – 3,2 |

|||

| footnotes = Физичка својства снега знатно варирају од догађаја до догађаја, од узорка до узорка, и током вемена. |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Датотека:SnowflakesWilsonBentley.jpg|мини|250п|Пахуљице (Вилсон Бентли, 1902.)]] |

|||

{{рут}} |

|||

'''Снијег''' (или '''снег''') је [[падавине|падавина]] у облику ледених [[кристал]]а [[вода|воде]], која се састоји од мноштва пахуљица. Иако се састоји од малих, неправилних делова, снег је у ствари зрнасти материјал.<ref name="Hobbs"> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

| last = Hobbs |

|||

| first = Peter V. |

|||

| title = Ice Physics |

|||

| publisher = Oxford University Press |

|||

| edition = |

|||

| date = 2010 |

|||

| location = Oxford |

|||

| pages = 856 |

|||

| isbn = 978-0199587711 }}</ref> Има отворену и меку структуру, док се не нађе под спољашњим притиском. Снег се формира када водена пара [[сублимација (физика)|сублимира]] високо у [[Земљина атмосфера|атмосфери]] на температури мањој од 0-{[[степен целзијуса|°C]]}- (32-{[[фаренхајт|°F]]}-), и након тога падне на земљу. Снијег такође може бити вјештачки направљен коришћењем сњежних топова, који уствари праве ситна зрна сличнија крупи. |

|||

Снег се задржава у облику замрзнуте кристалне воде током свог животног циклуса, starting when, under suitable conditions, the ice crystals form in the atmosphere, increase to millimeter size, precipitate and accumulate on surfaces, then metamorphose in place, and ultimately melt, slide or [[Sublimation (phase transition)|sublimate]] away. [[Snowstorms]] organize and develop by feeding on sources of atmospheric moisture and cold air. [[Snowflakes]] [[Nucleation|nucleate]] around particles in the atmosphere by attracting [[supercooling|supercooled]] water droplets, which freeze in hexagonal-shaped crystals. Snowflakes take on a variety of shapes, basic among these are platelets, needles, columns and [[Hard rime|rime]]. As snow accumulates into a [[snowpack]], it may blow into drifts. Over time, accumulated snow metamorphoses, by [[sintering]], [[sublimation (phase transition)|sublimation]] and [[freeze-thaw]]. Where the climate is cold enough for year-to-year accumulation, a [[glacier]] may form. Otherwise, snow typically melts seasonally, causing runoff into streams and rivers and recharging [[groundwater]]. |

|||

Снијег се формира када водена пара [[сублимација (физика)|сублимира]] високо у [[Земљина атмосфера|атмосфери]] на температури мањој од 0-{[[степен целзијуса|°C]]}- (32-{[[фаренхајт|°F]]}-), и након тога падне на земљу. Снијег такође може бити вјештачки направљен коришћењем сњежних топова, који уствари праве ситна зрна сличнија крупи. |

|||

Major snow-prone areas include the [[Polar regions of Earth|polar regions]], the upper half of the [[Northern Hemisphere]] and mountainous regions worldwide with sufficient moisture and cold temperatures. In the [[Southern Hemisphere]], snow is confined primarily to mountainous areas, apart from [[Antarctica]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

| last = Rees |

|||

| first = W. Gareth |

|||

| title = Remote Sensing of Snow and Ice |

|||

| publisher = CRC Press |

|||

| date = 2005 |

|||

| location = |

|||

| pages = 312 |

|||

| isbn = 9781420023749 |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=780IKxPcqpYC&pg=PA2&lpg=PA2&dq=Seasonal+snow+distribution+southern+Hemisphere&source=bl&ots=d4Ln6SMc_3&sig=FJA8jfhje6sJBUIJC7GO-ITm294&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjthLOViejQAhUkB8AKHfZJCLcQ6AEILjAD#v=onepage&q=Seasonal%20snow%20distribution%20southern%20Hemisphere&f=false |

|||

| access-date = December 9, 2016 }}</ref> |

|||

Snow affects such human activities as ''[[transportation]]'': creating the need for keeping roadways, wings, and windows clear; ''[[agriculture]]'': providing water to crops and safeguarding livestock; such ''[[sport]]s'' as [[skiing]], [[snowboarding]], [[Snowmobile|snowmachine]] travel; and ''[[warfare]]'': impairing target acquisition, degrading the performance of combatants and materiel, and impeding mobility. Snow affects ''[[ecosystem]]s'', as well, by providing an insulating layer during winter under which plants and animals are able to survive the cold.<ref name = Snowenclyclopedia>{{Citation |

|||

| author = Michael P. Bishop |

|||

| author2 = Helgi Björnsson |

|||

| author3 = Wilfried Haeberli |

|||

| author4 = Johannes Oerlemans |

|||

| author5 = John F. Shroder |

|||

| author6 = Martyn Tranter |

|||

| editor-last = Singh |

|||

| editor-first = Vijay P. |

|||

| editor2-last = Singh |

|||

| editor2-first = Pratap |

|||

| editor3-last = Haritashya |

|||

| editor3-first = Umesh K. |

|||

| contribution = |

|||

| contribution-url = |

|||

| series = |

|||

| year = 2011 |

|||

| pages = 1253 |

|||

| place = |

|||

| isbn = 9789048126415 |

|||

| title = Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers |

|||

| publisher = Springer Science & Business Media |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=mKKtQR4T-1MC&printsec=frontcover&dq=snow+formation&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjW27KZ4sbQAhWF4yYKHSurBWwQ6AEIKDAD#v=onepage&q=snow%20formation&f=false |

|||

| access-date = November 25, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

== Појава == |

== Појава == |

||

| Ред 23: | Ред 99: | ||

Снијег компресован у блокове се у неким дијеловима свијета користи као материјал за градњу објеката, нпр. [[иглу]] (сњежне [[Кућа|куће]]). |

Снијег компресован у блокове се у неким дијеловима свијета користи као материјал за градњу објеката, нпр. [[иглу]] (сњежне [[Кућа|куће]]). |

||

== Преципитација == |

|||

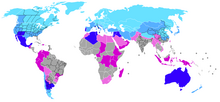

[[Датотека:Countries_receiving_snowfall.png|left|thumb|Worldwide occurrence of snowfall. Snow at reference above sea level (meters): |

|||

:{{Legend|#54E4E4|Below 500: annually.}} |

|||

{{Legend |#57AFFD|Below 500: annually, but not in all of its territory.}} |

|||

{{Legend|#0000FF|500: above annually, below occasionally.}} |

|||

{{Legend|#EC74E4|Above 500: annually.}} |

|||

{{Legend|#D300CA|Above 2,000: annually.}} |

|||

{{Legend|#C0C0C0|Any elevation: none.}}]] |

|||

[[Датотека:Neige 20150124 120130.ogv|thumb|left|Snowfall.]] |

|||

[[Датотека:De Lelie - Aalten - Winter - 2009.JPG|thumb|left|[[Aalten]], [[Netherlands]].]] |

|||

Snow develops in clouds that themselves are part of a larger weather system. The physics of snow crystal development in clouds results from a complex set of variables that include moisture content and temperatures. The resulting shapes of the falling and fallen crystals can be classified into a number of basic shapes and combinations, thereof. Occasionally, some plate-like, dendritic and stellar-shaped snowflakes can form under clear sky with a very cold temperature inversion present.<ref name = Classificationonground> |

|||

{{Citation |

|||

| last = Fierz |

|||

| first = C. |

|||

| last2 = Armstrong |

|||

| first2 = R.L. |

|||

| last3 = Durand |

|||

| first3 = Y. |

|||

| last4 = Etchevers |

|||

| first4 = P. |

|||

| last5 = Greene |

|||

| first5 = E. |

|||

| display-author=etal |

|||

| title = The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground |

|||

| place = Paris |

|||

| publisher = UNESCO |

|||

| series = IHP-VII Technical Documents in Hydrology |

|||

| volume = 83 |

|||

| year = 2009 |

|||

| pages = 80 |

|||

| url = http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001864/186462e.pdf |

|||

| access-date = November 25, 2016 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Формирање облака === |

|||

Snow clouds usually occur in the context of larger weather systems, the most important of which is the low pressure area, which typically incorporate warm and cold fronts as part of their circulation. Two additional and locally productive sources of snow are lake-effect (also sea-effect) storms and elevation effects, especially in mountains. |

|||

==== Области ниског притиска==== |

|||

{{Main article|Extratropical cyclone}} |

|||

[[File:Feb242007 blizzard.gif|thumb|right|Extratropical cyclonic snowstorm, February 24, 2007.]] |

|||

[[Extratropical cyclone|Mid-latitude cyclones]] are [[Low-pressure area|low pressure areas]] which are capable of producing anything from cloudiness and mild [[Winter storm#Snow|snow storms]] to heavy [[blizzard]]s.<ref name="ExtraLessonMillUni">{{cite web| title = ESCI 241 – Meteorology; Lesson 16 – Extratropical Cyclones | author = DeCaria| publisher = Department of Earth Sciences, [[Millersville University]]| date = December 7, 2005| url = http://www.atmos.millersville.edu/~adecaria/ESCI241/esci241_lesson16_cyclones.html | accessdate = June 21, 2009 |archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20080208224320/http://www.atmos.millersville.edu/~adecaria/ESCI241/esci241_lesson16_cyclones.html |archivedate = February 8, 2008}}</ref> During a hemisphere's [[autumn|fall]], winter, and spring, the atmosphere over continents can be cold enough through the depth of the [[troposphere]] to cause snowfall. In the Northern Hemisphere, the northern side of the low pressure area produces the most snow.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Tolme |

|||

| first = Paul |

|||

| title = Weather 101: How to track and bag the big storms |

|||

| journal = Ski Magazine |

|||

| volume = 69 |

|||

| issue = 4 |

|||

| pages = 298 |

|||

| publisher = Skimag.com |

|||

| location = |

|||

| date = December 2004 |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=t1DaXO7wF20C&pg=PA126&dq=low+pressure+area+snow&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiX7ajd78nQAhVh4YMKHbl8ALEQ6AEILDAD#v=onepage&q=low%20pressure%20area%20snow&f=false |

|||

| issn = 0037-6159 |

|||

| access-date = November 27, 2016}}</ref> For the southern mid-latitudes, the side of a cyclone that produces the most snow is the southern side. |

|||

====Фронтови==== |

|||

{{Main article|Weather front}} |

|||

[[Image:Snowsquall line-Bourrasque neige frontal NOAA.png|thumb|right|Frontal snowsquall moving toward [[Boston, Massachusetts]], [[United States]].]] |

|||

A [[cold front]], the leading edge of a cooler mass of air, can produce [[Snowsquall#Frontal snowsquall|frontal snowsqualls]]—an intense frontal [[convective]] line (similar to a [[rainband]]), when [[temperature]] is near freezing at the surface. The strong convection that develops has enough moisture to produce whiteout conditions at places which line passes over as the wind causes intense blowing snow.<ref name=EC-2>{{Cite web |

|||

|url= http://www.ec.gc.ca/meteo-weather/default.asp?lang=En&n=46FBA88B-1#Snow |

|||

|title= Snow |

|||

|work=Winter Hazards |

|||

|author= Meteorological Service of Canada |

|||

|author-link= Meteorological Service of Canada |

|||

|publisher=[[Environment Canada]] |

|||

|date= September 8, 2010 |

|||

|accessdate=October 4, 2010 |

|||

}}</ref> This type of snowsquall generally lasts less than 30 minutes at any point along its path but the motion of the line can cover large distances. Frontal squalls may form a short distance ahead of the surface cold front or behind the cold front where there may be a deepening low pressure system or a series of [[Trough (meteorology)|trough]] lines which act similar to a traditional cold frontal passage. In situations where squalls develop post-frontally it is not unusual to have two or three linear squall bands pass in rapid succession only separated by 25 miles (40 kilometers) with each passing the same point in roughly 30 minutes apart. In cases where there is a large amount of vertical growth and mixing the squall may develop embedded cumulonimbus clouds resulting in lightning and thunder which is dubbed [[thundersnow]]. |

|||

A [[warm front]] can produce snow for a period, as warm, moist air overrides below-freezing air and creates precipitation at the boundary. Often, snow transitions to rain in the warm sector behind the front.<ref name=EC-2/> |

|||

==== Утицаји језера и океана ==== |

|||

{{Main article|Lake-effect snow}} |

|||

[[File:Lake Effect Snow on Earth.jpg|thumb|Cold northwesterly wind over [[Lake Superior]] and [[Lake Michigan]] creating lake-effect snowfall.]] |

|||

Lake-effect snow is produced during cooler atmospheric conditions when a cold air mass moves across long expanses of warmer [[lake]] water, warming the lower layer of air which picks up [[water vapor]] from the lake, rises up through the colder air above, freezes and is deposited on the [[leeward]] (downwind) shores.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.noaa.gov/features/02_monitoring/lakesnow.html|title=NOAA - National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - Monitoring & Understanding Our Changing Planet|publisher=}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.comet.ucar.edu/class/smfaculty/byrd/sld012.htm |title=Fetch |publisher= |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080515101954/http://www.comet.ucar.edu/class/smfaculty/byrd/sld012.htm |archivedate=May 15, 2008 |df= }}</ref> |

|||

The same effect also occurs over bodies of salt water, when it is termed ''ocean-effect'' or ''bay-effect snow''. The effect is enhanced when the moving air mass is uplifted by the [[orographic lift|orographic]] influence of higher elevations on the downwind shores. This uplifting can produce narrow but very intense bands of precipitation, which deposit at a rate of many inches of snow each hour, often resulting in a large amount of total snowfall.<ref name=mass>{{cite book |last= Mass |first= Cliff |title= The Weather of the Pacific Northwest |year= 2008 |publisher= [[University of Washington Press]] |isbn= 978-0-295-98847-4 |page= 60}}</ref> |

|||

The areas affected by lake-effect snow are called [[snowbelt]]s. These include areas east of the [[Great Lakes]], the west coasts of northern Japan, the [[Kamchatka Peninsula]] in Russia, and areas near the [[Great Salt Lake]], [[Black Sea]], [[Caspian Sea]], [[Baltic Sea]], and parts of the northern Atlantic Ocean.<ref name="SCHMID">Thomas W. Schmidlin. [https://kb.osu.edu/dspace/bitstream/1811/23329/1/V089N4_101.pdf Climatic Summary of Snowfall and Snow Depth in the Ohio Snowbelt at Chardon.] Retrieved on March 1, 2008.</ref> |

|||

==== Утицаји планина ==== |

|||

{{Main article|Precipitation types#Orographic}} |

|||

[[Orography|Orographic]] or relief snowfall is caused when masses of air pushed by [[wind]] are forced up the side of elevated land formations, such as large [[mountain]]s. The lifting of air up the side of a mountain or range results in [[Adiabatic lapse rate|adiabatic]] cooling, and ultimately condensation and precipitation. Moisture is removed by orographic lift, leaving [[Foehn wind|drier, warmer air]] on the descending, leeward side.<ref name="MT">Physical Geography. [http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/8e.html CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081220230524/http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/8e.html |date=December 20, 2008 }} Retrieved on January 1, 2009.</ref> The resulting enhanced productivity of snow fall<ref>{{Citation |

|||

| first = Mark T. |

|||

| last = Stoelinga |

|||

| first2 = Ronald E. |

|||

| last2 = Stewart |

|||

| first3 = Gregory |

|||

| last3 = Thompson |

|||

| first4 = Julie M. |

|||

| last4 = Theriault |

|||

| editor-last = Chow |

|||

| editor-first = Fotini K. |

|||

| display-editors=etal |

|||

| title = Mountain Weather Research and Forecasting: Recent Progress and Current Challenges |

|||

| contribution = Micrographic processes within winter orographic cloud and precipitation systems |

|||

| series = Springer Atmospheric Sciences |

|||

| year = 2012 |

|||

| pages = 750 |

|||

| place = |

|||

| publisher = Springer Science & Business Media |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ihjFd5Q8oPMC&pg=PA3&dq=mountain+snow+storms&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiayqPTwsnQAhXJ4IMKHXa6Ca4Q6AEILDAD#v=onepage&q=Stoelinga&f=false |

|||

| access-date =November 27, 2016 }}</ref> and the [[Lapse rate|decrease in temperature]] with elevation<ref>{{cite book|author=Mark Zachary Jacobson|title=Fundamentals of Atmospheric Modeling|publisher=Cambridge University Press|edition=2nd|year=2005|isbn=0-521-83970-X}}</ref> means that snow depth and seasonal persistence of snowpack increases with elevation in snow-prone areas.<ref name = Snowenclyclopedia/><ref name = Singh> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

| last = P. |

|||

| first = Singh |

|||

| title = Snow and Glacier Hydrology |

|||

| publisher = Springer Science & Business Media |

|||

| series = Water Science and Technology Library |

|||

| volume = 37 |

|||

| date = 2001 |

|||

| location = |

|||

| pages = 756 |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=0VW6Tv0LVWkC&pg=PA75&dq=low+pressure+area+snow&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiX7ajd78nQAhVh4YMKHbl8ALEQ6AEINDAF#v=onepage&q=low%20pressure%20area%20snow&f=false |

|||

| access-date = November 27, 2016 |

|||

| isbn = 9780792367673 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Физика облака === |

|||

{{Main article|Snowflake}} |

|||

[[File:Feathery Snow Crystals (2217830221).jpg|thumb|Freshly fallen snowflakes.]] |

|||

A snowflake consists of roughly 10<sup>19</sup> water molecules, which are added to its core at different rates and in different patterns, depending on the changing temperature and humidity within the atmosphere that the snowflake falls through on its way to the ground. As a result, snowflakes vary among themselves, while following similar patterns.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2007/02/070213-snowflake.html|title="No Two Snowflakes the Same" Likely True, Research Reveals|author=John Roach|date=February 13, 2007|accessdate=July 14, 2009|publisher=[[National Geographic Society|National Geographic]] News}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|url=http://atmos-chem-phys.org/8/5669/2008/acp-8-5669-2008.pdf|title=Origin of diversity in falling snow|author=Jon Nelson|journal=Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics|date=September 26, 2008|accessdate=August 30, 2011|doi=10.5194/acp-8-5669-2008|volume=8|pages=5669–5682}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.aft.org/pubs-reports/american_educator/issues/winter04-05/Snowflake.pdf |title=Snowflake Science |author=Kenneth Libbrecht |journal=American Educator |date= 2004 |accessdate= 14. 7. 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081128094655/http://www.aft.org/pubs-reports/american_educator/issues/winter04-05/Snowflake.pdf |archivedate=November 28, 2008 }}</ref> |

|||

Snow crystals form when tiny [[supercool]]ed cloud droplets (about 10 [[micrometre|μm]] in diameter) [[freezing|freeze]]. These droplets are able to remain liquid at temperatures lower than {{convert|-18|°C|°F|0}}, because to freeze, a few [[molecules]] in the droplet need to get together by chance to form an arrangement similar to that in an ice lattice. Then the droplet freezes around this "nucleus". In warmer clouds an aerosol particle or "ice nucleus" must be present in (or in contact with) the droplet to act as a nucleus. Ice nuclei are very rare compared to that cloud condensation nuclei on which liquid droplets form. Clays, desert dust and biological particles can be nuclei.<ref name=Christner2008>{{cite journal |

|||

|author = Brent Q Christner |

|||

|author2=Cindy E Morris |author3=Christine M Foreman |author4=Rongman Cai |author5=David C Sands |

|||

|year = 2008 |

|||

|title = Ubiquity of Biological Ice Nucleators in Snowfall |

|||

|journal = Science |

|||

|volume = 319 |

|||

|issue = 5867 |

|||

|page = 1214 |

|||

|doi = 10.1126/science.1149757 |

|||

|pmid = 18309078 |

|||

|bibcode=2008Sci...319.1214C}}</ref> Artificial nuclei include particles of [[silver iodide]] and [[dry ice]], and these are used to stimulate precipitation in [[cloud seeding]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://amsglossary.allenpress.com/glossary/search?p=1&query=cloud+seeding&submit=Search|title=Cloud seeding|author=Glossary of Meteorology|year=2009|accessdate=June 28, 2009|publisher=[[American Meteorological Society]]}}</ref> |

|||

Once a droplet has frozen, it grows in the supersaturated environment—one where air is saturated with respect to ice when the temperature is below the freezing point. The droplet then grows by diffusion of water molecules in the air (vapor) onto the ice crystal surface where they are collected. Because water droplets are so much more numerous than the ice crystals due to their sheer abundance, the crystals are able to grow to hundreds of [[micrometer]]s or millimeters in size at the expense of the water droplets by the [[Wegener–Bergeron–Findeisen process]]. The corresponding depletion of water vapor causes the ice crystals to grow at the droplets' expense. These large crystals are an efficient source of precipitation, since they fall through the atmosphere due to their mass, and may collide and stick together in clusters, or aggregates. These aggregates are snowflakes, and are usually the type of ice particle that falls to the ground.<ref name="natgeojan07">{{cite journal|author=M. Klesius| title=The Mystery of Snowflakes| journal=National Geographic| volume=211| issue=1| year=2007| issn=0027-9358|page=20}}</ref> Although the ice is clear, scattering of light by the crystal facets and hollows/imperfections mean that the crystals often appear white in color due to [[diffuse reflection]] of the whole [[spectrum]] of [[light]] by the small ice particles.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=4T-aXFsMhAgC&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39|title=Hands-on Science: Light, Physical Science (matter) – Chapter 5: The Colors of Light|page=39|author=Jennifer E. Lawson|isbn=978-1-894110-63-1|year=2001|accessdate=June 28, 2009|publisher=Portage & Main Press}}</ref> |

|||

=== Кlasifiкaција снежних пахуљица === |

|||

{{Main article||Snowflake#Classification}} |

|||

[[File:Snowflakeschapte00warriala-p11-p21-p29-p39.jpg|thumb|right|An early classification of snowflakes by [[Israel Perkins Warren]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

| last = Warren |

|||

| first = Israel Perkins |

|||

| author-link = Israel Perkins Warren |

|||

| title = Snowflakes: a chapter from the book of nature |

|||

| publisher = American Tract Society |

|||

| date = 1863 |

|||

| location = Boston |

|||

| pages = 164 |

|||

| url = https://archive.org/details/snowflakeschapte00warriala |

|||

| access-date = November 25, 2016}}</ref>]] |

|||

[[Micrography]] of thousands of snowflakes from 1885 onward, starting with [[Wilson Bentley|Wilson Alwyn Bentley]], revealed the wide diversity of snowflakes within a classifiable set of patterns.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/263168|title=No two snowflakes are alike|date=December 7, 2008|author=Chris V. Thangham|accessdate=July 14, 2009|publisher=Digital Journal}}</ref> Closely matching snow crystals have been observed.<ref name="identical_crystals">{{cite news |

|||

|author= Randolph E. Schmid |

|||

|title= Identical snowflakes cause flurry |

|||

|agency= Associated Press |

|||

|publisher= The Boston Globe |

|||

|date= June 15, 1988 |

|||

|accessdate=November 27, 2008 |

|||

|quote= But there the two crystals were, side by side, on a glass slide exposed in a cloud on a research flight over Wausau, Wis. |

|||

|url= http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-8066647.html}}</ref> |

|||

Nakaya developed a crystal morphology diagram, relating crystal shapes to the temperature and moisture conditions under which they formed, which is summarized in the following table.<ref name = Snowenclyclopedia/> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+ Crystal structure morphology as a function of temperature and water saturation |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan=2| Temperature range |

|||

! colspan=2| Saturation range |

|||

! colspan=2| Types of snow crystal |

|||

|- |

|||

!°C |

|||

!°F |

|||

!g/m<sup>3</sup> |

|||

!oz/cu yd |

|||

! ''below'' saturation |

|||

! ''above'' saturation |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{convert|0|to|-3.5|C|F|0|disp=table}} |

|||

| {{convert|0.0|to|0.5|g/m3|oz/cuyd|disp=table}} |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Solid plates |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Thin plates |

|||

Dendrites |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{convert|-3.5|to|-10|C|F|0|disp=table}} |

|||

| {{convert|0.5|to|1.2|g/m3|oz/cuyd|disp=table}} |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Solid prisms |

|||

Hollow prisms |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Hollow prisms |

|||

Needles |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{convert|-10|to|-22|C|F|0|disp=table}} |

|||

| {{convert|1.2|to|1.4|g/m3|oz/cuyd|disp=table}} |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Thin plates |

|||

Solid plates |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Sectored plates |

|||

Dendrites |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{convert|-22|to|-40|C|F|0|disp=table}} |

|||

| {{convert|1.2|to|0.1|g/m3|oz/cuyd|disp=table}} |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Thin plates |

|||

Solid plates |

|||

| style="text-align:center;" | Columns |

|||

Prisms |

|||

|} |

|||

As Nakaya discovered, shape is also a function of whether the prevalent moisture is above or below saturation. Forms below the saturation line trend more towards solid and compact. Crystals formed in supersaturated air trend more towards lacy, delicate and ornate. Many more complex growth patterns also form such as side-planes, bullet-rosettes and also planar types depending on the conditions and ice nuclei.<ref name=BaileyHallett>{{cite journal |

|||

|author = Matthew Bailey |

|||

|author2=John Hallett |

|||

|year = 2004 |

|||

|title = Growth rates and habits of ice crystals between −20 and −70C |

|||

|journal = Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences |

|||

|volume = 61 |

|||

|issue = 5 |

|||

|pages = 514–544 |

|||

|doi = 10.1175/1520-0469(2004)061<0514:GRAHOI>2.0.CO;2 |

|||

|bibcode = 2004JAtS...61..514B}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author= Kenneth G. Libbrecht|url=http://www.its.caltech.edu/~atomic/snowcrystals/primer/primer.htm|title=A Snowflake Primer|date=October 23, 2006|publisher=[[California Institute of Technology]]|accessdate=June 28, 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Kenneth G. Libbrecht|title=The Formation of Snow Crystals|journal=American Scientist|volume=95|issue=1|pages=52–59 |date= 2007|doi=10.1511/2007.63.52}}</ref> If a crystal has started forming in a column growth regime, at around {{convert|-5|C|F|0}}, and then falls into the warmer plate-like regime, then plate or dendritic crystals sprout at the end of the column, producing so called "capped columns".<ref name="natgeojan07" /> |

|||

Magono and Lee devised a classification of freshly formed snow crystals that includes 80 distinct shapes. They documented each with micrographs.<ref name = magono-lee> |

|||

{{Citation |

|||

| last = Magono |

|||

| first = Choji |

|||

| last2 = Lee |

|||

| first2 = Chung Woo |

|||

| title = Meteorological Classification of Natural Snow Crystals |

|||

| place = Hokkaido |

|||

| publisher = Hokkaido University |

|||

| journal = Journal of the Faculty of Science |

|||

| volume = 3 |

|||

| issue = 4 |

|||

| date = 1966 |

|||

| edition = Geophysics |

|||

| series = 7 |

|||

| chapter-url = |

|||

| page = |

|||

| pages = 321–335 |

|||

| language = English |

|||

| url = http://hdl.handle.net/2115/8672 |

|||

| access-date = November 25, 2016 }}</ref> |

|||

== Референце == |

|||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

{{Commonscat|Snow}} |

{{Commonscat|Snow}} |

||

* [http://www.nsdl.arm.gov/Library/glossary.shtml#snowflake National Science Digital Library - Snowflake] |

* -{[http://www.nsdl.arm.gov/Library/glossary.shtml#snowflake National Science Digital Library - Snowflake]}- |

||

* [http://www.its.caltech.edu/~atomic/snowcrystals/faqs/faqs.htm Kenneth G. Libbrecht's Snowflake FAQ] |

* -{[http://www.its.caltech.edu/~atomic/snowcrystals/faqs/faqs.htm Kenneth G. Libbrecht's Snowflake FAQ]}- |

||

* -{[http://www.unep.org/geo/geo%5Fice/ United Nations Environment Programme: Global Outlook for Ice and Snow]}- |

|||

* -{[http://www.lowtem.hokudai.ac.jp/en/index.html Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University]}- |

|||

* -{[http://www.slf.ch/english_EN Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research]}- |

|||

* -{[http://nsidc.org National Snow and Ice Data Center of the United States]}- |

|||

* -{[http://design.medeek.com/resources/snow/groundsnowloads.html American Society of Civil Engineers ground snow loads interactive map for the continental US]}- |

|||

{{Падавине}} |

{{Падавине}} |

||

{{Климатски елементи}} |

{{Климатски елементи}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Категорија:Метеорологија]] |

[[Категорија:Метеорологија]] |

||

Верзија на датум 2. новембар 2017. у 21:04

| Снег | |

|---|---|

Норвешки воз пролази кроз снег | |

| Физичке особине | |

| Густина (ρ) | 0,1 – 0,8 g/cm3 |

| Механичка својства | |

| Затезна чврстоћа (σt) | 1,5 – 3,5 kPa[1] |

| Компресивна јачина (σc) | 3 – 7 MPa[1] |

| Термална својства | |

| Тачка топљења (Tm) | 0 °C |

| Топлотна проводљивост (k) За густине 0,1 до 0,5 g/cm3 | 0,05 – 0,7 W K−1 m−1 |

| Електрична својства | |

| Диелектрична константа (εr) За суви снег густине 0,1 од 0,9 g/cm3 | 1 – 3,2 |

| Физичка својства снега знатно варирају од догађаја до догађаја, од узорка до узорка, и током вемена. | |

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Снијег (или снег) је падавина у облику ледених кристала воде, која се састоји од мноштва пахуљица. Иако се састоји од малих, неправилних делова, снег је у ствари зрнасти материјал.[2] Има отворену и меку структуру, док се не нађе под спољашњим притиском. Снег се формира када водена пара сублимира високо у атмосфери на температури мањој од 0°C (32°F), и након тога падне на земљу. Снијег такође може бити вјештачки направљен коришћењем сњежних топова, који уствари праве ситна зрна сличнија крупи.

Снег се задржава у облику замрзнуте кристалне воде током свог животног циклуса, starting when, under suitable conditions, the ice crystals form in the atmosphere, increase to millimeter size, precipitate and accumulate on surfaces, then metamorphose in place, and ultimately melt, slide or sublimate away. Snowstorms organize and develop by feeding on sources of atmospheric moisture and cold air. Snowflakes nucleate around particles in the atmosphere by attracting supercooled water droplets, which freeze in hexagonal-shaped crystals. Snowflakes take on a variety of shapes, basic among these are platelets, needles, columns and rime. As snow accumulates into a snowpack, it may blow into drifts. Over time, accumulated snow metamorphoses, by sintering, sublimation and freeze-thaw. Where the climate is cold enough for year-to-year accumulation, a glacier may form. Otherwise, snow typically melts seasonally, causing runoff into streams and rivers and recharging groundwater.

Major snow-prone areas include the polar regions, the upper half of the Northern Hemisphere and mountainous regions worldwide with sufficient moisture and cold temperatures. In the Southern Hemisphere, snow is confined primarily to mountainous areas, apart from Antarctica.[3]

Snow affects such human activities as transportation: creating the need for keeping roadways, wings, and windows clear; agriculture: providing water to crops and safeguarding livestock; such sports as skiing, snowboarding, snowmachine travel; and warfare: impairing target acquisition, degrading the performance of combatants and materiel, and impeding mobility. Snow affects ecosystems, as well, by providing an insulating layer during winter under which plants and animals are able to survive the cold.[1]

Појава

Сњежне падавине зависе од доба године и локације, која укључује географску ширину, надморску висину и друге факторе који уопштено утичу на временске прилике.

Неке планине, од којих и неке близу екватора, имају стални сњежни покривач на врху, укључујући Килиманџаро у Танзанији. Обрнуто, многи дијелови Арктика и Антарктика имају малу количину сњежних падавина, упркос великој хладноћи.

Највеће укупне падавине на свијету су измјерене на планини Маунт Бејкер (Вашингтон, САД) током сезоне 1998-1999. када су износиле 28 метара, а највећа количина дневних падавина је измјерена на Сребрном језеру (Колорадо, САД) 1921. године и износи 1,93 метара.

Рекреација

Врсте рекреације за које је неопходан снијег:

- зимски спортови попут скијања, санкања и других спортова

- прављење Сњешка Бијелића или кула од снијега

- грудвање (међусобно гађање грудвама, збијеним снежним куглама)

На мјестима гдје је довољно хладно, али нема падавина, могуће је користити сњежне топове за довољну количину снијега за зимске спортове.

Снијег компресован у блокове се у неким дијеловима свијета користи као материјал за градњу објеката, нпр. иглу (сњежне куће).

Преципитација

Snow develops in clouds that themselves are part of a larger weather system. The physics of snow crystal development in clouds results from a complex set of variables that include moisture content and temperatures. The resulting shapes of the falling and fallen crystals can be classified into a number of basic shapes and combinations, thereof. Occasionally, some plate-like, dendritic and stellar-shaped snowflakes can form under clear sky with a very cold temperature inversion present.[4]

Формирање облака

Snow clouds usually occur in the context of larger weather systems, the most important of which is the low pressure area, which typically incorporate warm and cold fronts as part of their circulation. Two additional and locally productive sources of snow are lake-effect (also sea-effect) storms and elevation effects, especially in mountains.

Области ниског притиска

Mid-latitude cyclones are low pressure areas which are capable of producing anything from cloudiness and mild snow storms to heavy blizzards.[5] During a hemisphere's fall, winter, and spring, the atmosphere over continents can be cold enough through the depth of the troposphere to cause snowfall. In the Northern Hemisphere, the northern side of the low pressure area produces the most snow.[6] For the southern mid-latitudes, the side of a cyclone that produces the most snow is the southern side.

Фронтови

A cold front, the leading edge of a cooler mass of air, can produce frontal snowsqualls—an intense frontal convective line (similar to a rainband), when temperature is near freezing at the surface. The strong convection that develops has enough moisture to produce whiteout conditions at places which line passes over as the wind causes intense blowing snow.[7] This type of snowsquall generally lasts less than 30 minutes at any point along its path but the motion of the line can cover large distances. Frontal squalls may form a short distance ahead of the surface cold front or behind the cold front where there may be a deepening low pressure system or a series of trough lines which act similar to a traditional cold frontal passage. In situations where squalls develop post-frontally it is not unusual to have two or three linear squall bands pass in rapid succession only separated by 25 miles (40 kilometers) with each passing the same point in roughly 30 minutes apart. In cases where there is a large amount of vertical growth and mixing the squall may develop embedded cumulonimbus clouds resulting in lightning and thunder which is dubbed thundersnow.

A warm front can produce snow for a period, as warm, moist air overrides below-freezing air and creates precipitation at the boundary. Often, snow transitions to rain in the warm sector behind the front.[7]

Утицаји језера и океана

Lake-effect snow is produced during cooler atmospheric conditions when a cold air mass moves across long expanses of warmer lake water, warming the lower layer of air which picks up water vapor from the lake, rises up through the colder air above, freezes and is deposited on the leeward (downwind) shores.[8][9]

The same effect also occurs over bodies of salt water, when it is termed ocean-effect or bay-effect snow. The effect is enhanced when the moving air mass is uplifted by the orographic influence of higher elevations on the downwind shores. This uplifting can produce narrow but very intense bands of precipitation, which deposit at a rate of many inches of snow each hour, often resulting in a large amount of total snowfall.[10]

The areas affected by lake-effect snow are called snowbelts. These include areas east of the Great Lakes, the west coasts of northern Japan, the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, and areas near the Great Salt Lake, Black Sea, Caspian Sea, Baltic Sea, and parts of the northern Atlantic Ocean.[11]

Утицаји планина

Orographic or relief snowfall is caused when masses of air pushed by wind are forced up the side of elevated land formations, such as large mountains. The lifting of air up the side of a mountain or range results in adiabatic cooling, and ultimately condensation and precipitation. Moisture is removed by orographic lift, leaving drier, warmer air on the descending, leeward side.[12] The resulting enhanced productivity of snow fall[13] and the decrease in temperature with elevation[14] means that snow depth and seasonal persistence of snowpack increases with elevation in snow-prone areas.[1][15]

Физика облака

A snowflake consists of roughly 1019 water molecules, which are added to its core at different rates and in different patterns, depending on the changing temperature and humidity within the atmosphere that the snowflake falls through on its way to the ground. As a result, snowflakes vary among themselves, while following similar patterns.[16][17][18]

Snow crystals form when tiny supercooled cloud droplets (about 10 μm in diameter) freeze. These droplets are able to remain liquid at temperatures lower than −18 °C (0 °F), because to freeze, a few molecules in the droplet need to get together by chance to form an arrangement similar to that in an ice lattice. Then the droplet freezes around this "nucleus". In warmer clouds an aerosol particle or "ice nucleus" must be present in (or in contact with) the droplet to act as a nucleus. Ice nuclei are very rare compared to that cloud condensation nuclei on which liquid droplets form. Clays, desert dust and biological particles can be nuclei.[19] Artificial nuclei include particles of silver iodide and dry ice, and these are used to stimulate precipitation in cloud seeding.[20]

Once a droplet has frozen, it grows in the supersaturated environment—one where air is saturated with respect to ice when the temperature is below the freezing point. The droplet then grows by diffusion of water molecules in the air (vapor) onto the ice crystal surface where they are collected. Because water droplets are so much more numerous than the ice crystals due to their sheer abundance, the crystals are able to grow to hundreds of micrometers or millimeters in size at the expense of the water droplets by the Wegener–Bergeron–Findeisen process. The corresponding depletion of water vapor causes the ice crystals to grow at the droplets' expense. These large crystals are an efficient source of precipitation, since they fall through the atmosphere due to their mass, and may collide and stick together in clusters, or aggregates. These aggregates are snowflakes, and are usually the type of ice particle that falls to the ground.[21] Although the ice is clear, scattering of light by the crystal facets and hollows/imperfections mean that the crystals often appear white in color due to diffuse reflection of the whole spectrum of light by the small ice particles.[22]

Кlasifiкaција снежних пахуљица

Micrography of thousands of snowflakes from 1885 onward, starting with Wilson Alwyn Bentley, revealed the wide diversity of snowflakes within a classifiable set of patterns.[24] Closely matching snow crystals have been observed.[25]

Nakaya developed a crystal morphology diagram, relating crystal shapes to the temperature and moisture conditions under which they formed, which is summarized in the following table.[1]

| Temperature range | Saturation range | Types of snow crystal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | °F | g/m3 | oz/cu yd | below saturation | above saturation |

| 0 to −35 | 32 to −31 | 00 to 05 | 0,00 to 0,13 | Solid plates | Thin plates

Dendrites |

| −35 to −10 | −31 to 14 | 05 to 12 | 0,13 to 0,32 | Solid prisms

Hollow prisms |

Hollow prisms

Needles |

| −10 to −22 | 14 to −8 | 12 to 14 | 0,32 to 0,38 | Thin plates

Solid plates |

Sectored plates

Dendrites |

| −22 to −40 | −8 to −40 | 12 to 01 | 0,324 to 0,027 | Thin plates

Solid plates |

Columns

Prisms |

As Nakaya discovered, shape is also a function of whether the prevalent moisture is above or below saturation. Forms below the saturation line trend more towards solid and compact. Crystals formed in supersaturated air trend more towards lacy, delicate and ornate. Many more complex growth patterns also form such as side-planes, bullet-rosettes and also planar types depending on the conditions and ice nuclei.[26][27][28] If a crystal has started forming in a column growth regime, at around −5 °C (23 °F), and then falls into the warmer plate-like regime, then plate or dendritic crystals sprout at the end of the column, producing so called "capped columns".[21]

Magono and Lee devised a classification of freshly formed snow crystals that includes 80 distinct shapes. They documented each with micrographs.[29]

Референце

- ^ а б в г д Michael P. Bishop; Helgi Björnsson; Wilfried Haeberli; Johannes Oerlemans; John F. Shroder; Martyn Tranter (2011), Singh, Vijay P.; Singh, Pratap; Haritashya, Umesh K., ур., Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers, Springer Science & Business Media, стр. 1253, ISBN 9789048126415, Приступљено 25. 11. 2016

- ^ Hobbs, Peter V. (2010). Ice Physics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. стр. 856. ISBN 978-0199587711.

- ^ Rees, W. Gareth (2005). Remote Sensing of Snow and Ice. CRC Press. стр. 312. ISBN 9781420023749. Приступљено 9. 12. 2016.

- ^

Fierz, C.; Armstrong, R.L.; Durand, Y.; Etchevers, P.; Greene, E. (2009), The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground (PDF), IHP-VII Technical Documents in Hydrology, 83, Paris: UNESCO, стр. 80, Приступљено 25. 11. 2016 Непознати параметар

|display-author=игнорисан (помоћ) - ^ DeCaria (7. 12. 2005). „ESCI 241 – Meteorology; Lesson 16 – Extratropical Cyclones”. Department of Earth Sciences, Millersville University. Архивирано из оригинала 8. 2. 2008. г. Приступљено 21. 6. 2009.

- ^ Tolme, Paul (децембар 2004). „Weather 101: How to track and bag the big storms”. Ski Magazine. Skimag.com. 69 (4): 298. ISSN 0037-6159. Приступљено 27. 11. 2016.

- ^ а б Meteorological Service of Canada (8. 9. 2010). „Snow”. Winter Hazards. Environment Canada. Приступљено 4. 10. 2010.

- ^ „NOAA - National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - Monitoring & Understanding Our Changing Planet”.

- ^ „Fetch”. Архивирано из оригинала 15. 5. 2008. г.

- ^ Mass, Cliff (2008). The Weather of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press. стр. 60. ISBN 978-0-295-98847-4.

- ^ Thomas W. Schmidlin. Climatic Summary of Snowfall and Snow Depth in the Ohio Snowbelt at Chardon. Retrieved on March 1, 2008.

- ^ Physical Geography. CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes. Архивирано децембар 20, 2008 на сајту Wayback Machine Retrieved on January 1, 2009.

- ^ Stoelinga, Mark T.; Stewart, Ronald E.; Thompson, Gregory; Theriault, Julie M. (2012), „Micrographic processes within winter orographic cloud and precipitation systems”, Ур.: Chow, Fotini K.; et al., Mountain Weather Research and Forecasting: Recent Progress and Current Challenges, Springer Atmospheric Sciences, Springer Science & Business Media, стр. 750, Приступљено 27. 11. 2016

- ^ Mark Zachary Jacobson (2005). Fundamentals of Atmospheric Modeling (2nd изд.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83970-X.

- ^ P., Singh (2001). Snow and Glacier Hydrology. Water Science and Technology Library. 37. Springer Science & Business Media. стр. 756. ISBN 9780792367673. Приступљено 27. 11. 2016.

- ^ John Roach (13. 2. 2007). „"No Two Snowflakes the Same" Likely True, Research Reveals”. National Geographic News. Приступљено 14. 7. 2009.

- ^ Jon Nelson (26. 9. 2008). „Origin of diversity in falling snow” (PDF). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 8: 5669—5682. doi:10.5194/acp-8-5669-2008. Приступљено 30. 8. 2011.

- ^ Kenneth Libbrecht (2004). „Snowflake Science” (PDF). American Educator. Архивирано из оригинала (PDF) 28. 11. 2008. г. Приступљено 14. 7. 2009.

- ^ Brent Q Christner; Cindy E Morris; Christine M Foreman; Rongman Cai; David C Sands (2008). „Ubiquity of Biological Ice Nucleators in Snowfall”. Science. 319 (5867): 1214. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1214C. PMID 18309078. doi:10.1126/science.1149757.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). „Cloud seeding”. American Meteorological Society. Приступљено 28. 6. 2009.

- ^ а б M. Klesius (2007). „The Mystery of Snowflakes”. National Geographic. 211 (1): 20. ISSN 0027-9358.

- ^ Jennifer E. Lawson (2001). Hands-on Science: Light, Physical Science (matter) – Chapter 5: The Colors of Light. Portage & Main Press. стр. 39. ISBN 978-1-894110-63-1. Приступљено 28. 6. 2009.

- ^ Warren, Israel Perkins (1863). Snowflakes: a chapter from the book of nature. Boston: American Tract Society. стр. 164. Приступљено 25. 11. 2016.

- ^ Chris V. Thangham (7. 12. 2008). „No two snowflakes are alike”. Digital Journal. Приступљено 14. 7. 2009.

- ^ Randolph E. Schmid (15. 6. 1988). „Identical snowflakes cause flurry”. The Boston Globe. Associated Press. Приступљено 27. 11. 2008. „But there the two crystals were, side by side, on a glass slide exposed in a cloud on a research flight over Wausau, Wis.”

- ^ Matthew Bailey; John Hallett (2004). „Growth rates and habits of ice crystals between −20 and −70C”. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 61 (5): 514—544. Bibcode:2004JAtS...61..514B. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(2004)061<0514:GRAHOI>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Kenneth G. Libbrecht (23. 10. 2006). „A Snowflake Primer”. California Institute of Technology. Приступљено 28. 6. 2009.

- ^ Kenneth G. Libbrecht (2007). „The Formation of Snow Crystals”. American Scientist. 95 (1): 52—59. doi:10.1511/2007.63.52.

- ^ Magono, Choji; Lee, Chung Woo (1966), „Meteorological Classification of Natural Snow Crystals”, Journal of the Faculty of Science, 7 (на језику: енглески) (Geophysics изд.), Hokkaido: Hokkaido University, 3 (4): 321—335, Приступљено 25. 11. 2016

Спољашње везе

- National Science Digital Library - Snowflake

- Kenneth G. Libbrecht's Snowflake FAQ

- United Nations Environment Programme: Global Outlook for Ice and Snow

- Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University

- Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research

- National Snow and Ice Data Center of the United States

- American Society of Civil Engineers ground snow loads interactive map for the continental US