Maurijsko carstvo

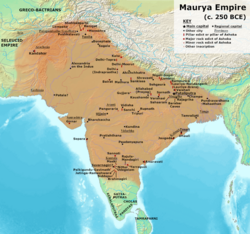

Maurja carstvo je bilo prostrano carstvo u drevnoj Indiji tokom gvozdenog doba, kojom je vladala dinastija Maurja od 322. p. n. e. do 185. p. n. e.[1] Carstvo vodi poreklo od kraljevstva Magada u Indogangskoj niziji (današnji Bihar i istočni Utar Pradeš) na istočnoj strani Indijskog potkontinenta Glavni grad carstva je bila Pataliputra (današnja Patna). Carstvo je osnovao Čandragupta Maurija, koji je zbacio dinastiju Nanda i uz Čanakjinu pomoć brzo širio svoju vlast na zapad preko centralne i zapadne Indije, iskoristivši poremećaja lokalnih vlasti u po povlačenju na zapad vojske Aleksandra Velikog. Do 316. p. n. e. carstvo je potpuno zauzelo severozapadnu Indiju, pobedivši i pokorivši satrape koje je postavio Aleksandar. Čandragupta je zatim odbio invaziju Seleuka I, osvojivši još teritorija zapadno od reke Ind.

Maurja carstvo je bilo jedno od najvećih carstava u svetu u svoje vreme.[11][12][13] Na svom vrhuncu carstvo se prostiralo na severu duž prirodnih granica Himalaja, na istoku u Asam, na zapadu u Beludžistan (jugozapadni Pakistan i jugoistočni Iran) i planina Hindukuš u današnjem Avganistanu. Carstvo su u centralne i južne regije Indije proširili carevi Čandragupta i Bindusara, ali oni nije obuhvatalo mali deo plemenskih i šumovitih regija kod Kalinge (današnja Odiša), sve dok ih nije pokorio Ašoka. Carstvo je propalo oko 50 godina nakon što je okončana Ašokina vladavina, i raspalo se 185. p. n. e. sa uspotavljanjem dinastije Šunga u Magadi.

Pod Čandraguptom i njegovim naslednicima, uznapredovale su unutrašnja i spoljna trgovine, poljoprivreda i ekonomske aktivnost i proširila se širom Indije zahvaljujući stvaranju jedinstvenog i efikasnog sistema finansija, upravljanja i bezbednosti. Nakon Kalingskog rata carstvo je uživalo skoro pola veka mira i bezbednosti pod Ašokom. Maurjanska Indija je takođe uživala u eri društvene harmonije, verske transformaciju i širenje nauke i znanja. Čandraguptino prihvatanje đainizma je pojačalo društvenu i versku obnovu i reforme širom njegove države, dok se za Ašokino prihvatanje budizma govorilo da je bilo temelj vladavine društvenog i političkog mira i nenasilja širom cele Indije. Ašoka je podsticao širenje budističkih ideala u Šri Lanku, jugoistočnu Aziju, zapadnu Aziju i mediteransku Evropu.

Stanovništvo carstva je procenjena na oko 50-60 miliona, što čini Maurja carstvo jednim od najmnogoljudnijim carstava antike. Period vladavine Maurja u južnoj Aziji areheološki spada u vreme kulture severne crne glačane keramike). Artašastra i Ašokini edikti su glavni pisani izvori iz doba Maurja. Lavlji kapitel Ašoke iz Sarnata je postao državni amblem Indije.

Reference[uredi | uredi izvor]

- ^ Dyson, Tim (2018), A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day, Oxford University Press, str. 16—17, ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8 Quote: "Magadha power came to extend over the main cities and communication routes of the Ganges basin. Then, under Chandragupta Maurya (c.321–297 bce), and subsequently Ashoka his grandson, Pataliputra became the centre of the loose-knit Mauryan 'Empire' which during Ashoka's reign (c.268–232 bce) briefly had a presence throughout the main urban centres and arteries of the subcontinent, except for the extreme south."

- ^ Hermann Kulke 2004, str. 69-70.

- ^ Stein, Burton (2010), A History of India, John Wiley & Sons, str. 74, ISBN 978-1-4443-2351-1, „In the past it was not uncommon for historians to conflate the vast space thus outlined with the oppressive realm described in the Arthashastra and to posit one of the earliest and certainly one of the largest totalitarian regimes in all of history. Such a picture is no longer considered believable; at present what is taken to be the realm of Ashoka is a discontinuous set of several core regions separated by very large areas occupied by relatively autonomous peoples.”

- ^ Ludden, David (2013), India and South Asia: A Short History, Oneworld Publications, str. 29—3, ISBN 978-1-78074-108-6, „The geography of the Mauryan Empire resembled a spider with a small dense body and long spindly legs. The highest echelons of imperial society lived in the inner circle composed of the ruler, his immediate family, other relatives, and close allies, who formed a dynastic core. Outside the core, empire travelled stringy routes dotted with armed cities. ... In most janapadas, the Mauryan Empire consisted of strategic urban sites connected loosely to vast hinterlands through lineages and local elites who were there when the Mauryas arrived and were still in control when they left.”

- ^ a b v Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE – 200 CE, Cambridge University Press, str. 451—466, ISBN 978-1-316-41898-7

- ^ Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE – 200 CE, Cambridge University Press, str. 453, ISBN 978-1-316-41898-7

- ^ Dyson, Tim (2018), A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day, Oxford University Press, str. 16—17, ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8, „Magadha power came to extend over the main cities and communication routes of the Ganges basin. Then, under Chandragupta Maurya (c.321–297 bce), and subsequently Ashoka his grandson, Pataliputra became the centre of the loose-knit Mauryan 'Empire' which during Ashoka's reign (c.268–232 bce) briefly had a presence throughout the main urban centres and arteries of the subcontinent, except for the extreme south.”

- ^ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1920), The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, Clarendon Press, str. 104—106

- ^ Majumdar, R. C.; Raychaudhuri, H. C.; Datta, Kalikinkar (1950), An Advanced History of India (Second izd.), Macmillan & Company, str. 104

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. A Historical Atlas of South Asia, 2nd ed. (University of Minnesota, 1992), Plate III.B.4b (p.18) and Plate XIV.1a-c (p.145)

- ^ Ludden, David (2013), India and South Asia: A Short History, Oneworld Publications, str. 29—30, ISBN 978-1-78074-108-6 Quote: "The geography of the Mauryan Empire resembled a spider with a small dense body and long spindly legs. The highest echelons of imperial society lived in the inner circle composed of the ruler, his immediate family, other relatives, and close allies, who formed a dynastic core. Outside the core, empire travelled stringy routes dotted with armed cities. Outside the palace, in the capital cities, the highest ranks in the imperial elite were held by military commanders whose active loyalty and success in war determined imperial fortunes. Wherever these men failed or rebelled, dynastic power crumbled. ... Imperial society flourished where elites mingled; they were its backbone, its strength was theirs. Kautilya's Arthasastra indicates that imperial power was concentrated in its original heartland, in old Magadha, where key institutions seem to have survived for about seven hundred years, down to the age of the Guptas. Here, Mauryan officials ruled local society, but not elsewhere. In provincial towns and cities, officials formed a top layer of royalty; under them, old conquered royal families were not removed, but rather subordinated. In most janapadas, the Mauryan Empire consisted of strategic urban sites connected loosely to vast hinterlands through lineages and local elites who were there when the Mauryas arrived and were still in control when they left."

- ^ Hermann Kulke 2004, str. xii, 448.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (1990). A History of India, Volume 1. Penguin Books. str. 384. ISBN 0-14-013835-8.

Literatura[uredi | uredi izvor]

- Alain Daniélou (2003). A Brief History of India. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-59477-794-3.

- Arthur Llewellyn Basham (1951). History and doctrines of the Ājīvikas: a vanished Indian religion. foreword by L. D. Barnett (1 izd.). London: Luzac.

- Burton Stein (1998). A History of India (1st ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Geoffrey Samuel (2010). The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press.

- H. C. Raychaudhuri (1988) [1967]. „India in the Age of the Nandas”. Ur.: K. A. Nilakanta Sastri. Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second izd.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1.

- H. C. Raychaudhuri; B. N. Mukherjee (1996). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. Oxford University Press.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India (4th izd.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15481-2.

- Irfan Habib; Vivekanand Jha (2004). Mauryan India. A People's History of India. Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books. ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8.

- J. E. Schwartzberg (1992). A Historical Atlas of South Asia. University of Oxford Press.

- John Keay (2000). India, a History. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1.

- John D Grainger (2014). Seleukos Nikator (Routledge Revivals): Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-80098-9.

- Hemacandra (1998), The Lives of the Jain Elders, Prevod: R.C.C. Fynes, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283227-6

- Kailash Chand Jain (1991). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena (2002), Encyclopaedia of Buddhism: Acala, Government of Ceylon

- R. K. Mookerji (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0.

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th izd.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- R. C. Majumdar (2003) [1952]. Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0436-8.

- Roy, Kaushik (2012), Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8

- Sen, R.K. (1895), „Origin of the Maurya of Magadha and of Chanakya”, Journal of the Buddhist Text Society of India, The Society

- S. N. Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- Romila Thapar (2004) [first published by Penguin in 2002]. Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

- Thapar, Romila (2013), The Past Before Us, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72651-2

Spoljašnje veze[uredi | uredi izvor]

- Livius.org: Maurya dynasty Arhivirano na sajtu Wayback Machine (26. februar 2012)

- Extent of the Empire

- Ashoka's Edicts