Камено доба — разлика између измена

м грешкица |

. |

||

| Ред 5: | Ред 5: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|} |

||

[[Датотека:Kärnyxa av flinta, Nordisk familjebok.jpg|мини| |

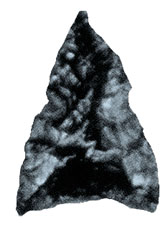

[[Датотека:Kärnyxa av flinta, Nordisk familjebok.jpg|мини|250п|Оруђе од [[кремен]]а]] |

||

{{rut}} |

|||

'''Камено доба''' означава најстарије раздобље [[преисторија|праисторије]]. Прву периодизацију праисторије дефинисао је дански археолог Кристијан Томасен [[1836]]. године. Његов „[[Метално доба|тропериодни систем]]“ којим се праисторија дели на камено, [[Бронзано доба|бронзано]] и [[гвоздено доба]] постаје темељем свих каснијих периодизација. Назив је добило по камену од ког су претежно израђивани алати. |

'''Камено доба''' означава најстарије раздобље [[преисторија|праисторије]]. Прву периодизацију праисторије дефинисао је дански археолог Кристијан Томасен [[1836]]. године. Његов „[[Метално доба|тропериодни систем]]“ којим се праисторија дели на камено, [[Бронзано доба|бронзано]] и [[гвоздено доба]] постаје темељем свих каснијих периодизација. Назив је добило по камену од ког су претежно израђивани алати. Камено доба је широк [[преисторија |преисторијски]] период током кога је [[Камен (геологија) |камен]] био у широкој употреби за прављење оруђа са ивицом или врхом. Овај период је трајао око 3,4 милиона година<ref name="nhm.ac.uk">https://web.archive.org/web/20100818123718/http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2010/august/oldest-tool-use-and-meat-eating-revealed75831.html</ref> и завшио се између 8700 п. н. е. и 2000 п. н. е. са развојом [[Обрада метала |обраде метала]]. |

||

Године [[1865]]. [[Уједињено Краљевство|британски]] археолог [[Џон Лубок]] камено доба дели на старије камено доба или [[палеолит]] и млађе камено доба или [[неолит]]. Године [[1866]]. Вентроп је додао средње камено доба или [[мезолит]]. |

Године [[1865]]. [[Уједињено Краљевство|британски]] археолог [[Џон Лубок]] камено доба дели на старије камено доба или [[палеолит]] и млађе камено доба или [[неолит]]. Године [[1866]]. Вентроп је додао средње камено доба или [[мезолит]]. |

||

== Историјски значај == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Еволуција човека график}} |

|||

* [[палеолит]] |

|||

[[Датотека:Awashrivermap.png|thumb|лево|250px|Модерна [[Аваш (река)|Аваш река]], Етиопија, наследница Палаео-Аваша, извора седимената у којима су пронађени најстарији алати каменог доба]] |

|||

* [[епипалеолит]] |

|||

* [[мезолит]] |

|||

Камено доба се подудара са еволуцијом рода -{''[[Homo]]''}-. Једини могући изузетак је рано камено доба, током кога је могуће да су врсте које су претходиле врсти -{''Homo''}- производиле оруђе.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Ko|first1=Kwang Hyun|title=Origins of human intelligence: The chain of tool-making and brain evolution|journal=Anthropological Notebooks|date=2016|volume=22|issue=1|pages=5–22|url=http://www.drustvo-antropologov.si/AN/PDF/2016_1/Anthropological_Notebooks_XXII_1_Ko.pdf}}</ref> Судећи по добу и локацији постојеће евиденције, колевка људског рода је био систем [[East African Rift |Источно Афричког расцепа]], посебно предео севера [[Етиопија |Етиопије]], где се граничи са [[Травњак |пашњацима]]. Најближи сродник међу другим живућим [[примат]]има, род -{''[[Шимпанза|Pan]]''}-, представља грану која је наставила да обитава у дубокој шуми, где су примати еволуирали. Расцеп је служио као пролаз за кретање у [[Јужна Африка |јужну Африку]] а исто тако северно низ [[Нил]] у сверну Африку и кроз натавак процепа до [[Левант]]а и на огромне травњаке Азије. |

|||

* [[протонеолит]] |

|||

* [[прекерамички неолит]] |

|||

Почевши пре око 4 милиона година ([[Година|-{mya}-]]) један [[биом]] се успоставио од Јужне Африке кроз процеп, северну Африку, и кроз Азију до модерне Кине, који се назива „трансконтинентални 'саванастан'”.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=106}}</ref> Полазећи од пашњака у процепу, -{''[[Homo erectus]]''}-, претходник савремених људи, је нашао [[Еколошка ниша |еколошку нишу]] као градитељ алата и временом је развио зависност од тога, постајући „оруђима опремљен становник [[савана |саване]]”.<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=147}}</ref> |

|||

* [[неолит]] |

|||

== Камено доба у археологији == |

|||

=== Почетак каменог доба === |

|||

[[Датотека:Arrowhead.jpg|thumb|left|250px|[[Опсидијан]]ски [[пројектилски врх]] ]] |

|||

Најстарија посредна евиденција о употреби каменог оруђа су фосилизоване животињске кости са трагом употребе алата; оне су око 3,4 милиона годна старе и нађене су у долини Аваш у Етиопији.<ref name="nhm.ac.uk"/> Археолошка открића у Кенији из 2015, указују на могућност да је то могућа најстарија хоминидна употреба оруђа до данас позната, из чега следи да је -{''[[Kenyanthropus]] platyops''}- (3,2 до 3,5 милиона година стар [[плиоцен]]ски хоминински фосил откривен на језеру Туркана у Кенији 1999. године) вероватно био најранији познати корисник оруђа.<ref>[http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-32804177 BBC News, 21/05/2015: Oldest stone tools pre-date earliest humans]</ref> |

|||

Најстарија камена оруђа су ископана на локацији [[Ломекви]] 3 у западној [[Turkana County|Туркани]] у северзападној Кенији, и стара су око 3,3 милиона година.<ref name="Harmand 2015">{{cite journal|last1=Harmand|first1=Sonia|title=3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya|journal=Nature|date=21 May 2015|volume=521|pages=310–315|doi=10.1038/nature14464|display-authors=etal|pmid=25993961}}</ref> Пре открића тих „Ломеквијанских” оруђа, најстарија позната оруђа су била нађена на неколико локација у Гони, [[Етиопија]], у седиментима палео-Авашке реке, који су помогли у њиховом датирању. Сва та оруђа птичу из Бусидамске формације, која лежи изнад [[Дискорданција |дисконформитета]], или недостајућег слоја, који одговара периоду од пре 2,9 до 2,7 милиона година. Најстарије локације које садрже оруђа су датиране на пре 2,6–2,55 милиона година.<ref>{{harvnb|Rogers|Semaw|2009|pp=162–163}}</ref> Једна од најупечатљивијих околности ових локација је да су оне из касног [[плиоцен]]а, док се пре њиховог открића сматрало да су алати еволуирали само у [[плеистоцен]]у. Екскаватори на локалитету напомињу да су:<ref>{{harvnb|Rogers|Semaw|2009|p=155}}</ref> |

|||

:"... најранији израђивачи камених оруђа били вешти [[Окресивање |окресивачи]] .... Могући разлози иза овог наизглед наглог преласка из одсуства камених алата на његово присуство укључују ... празнине у геолошком запису." |

|||

Врсте које су направиле плиоценска оруђа нису познате. Фрагменти -{''[[Australopithecus garhi]]''}-, -{''[[Australopithecus aethiopicus]]''}-<ref>As to whether aethiopicus is the genus ''[[Australopithecus]]'' or the genus ''[[Paranthropus]]'', broken out to include the more robust forms, anthropological opinion is divided and both usages occur in the professional sources.</ref> и -{''Homo''}-, вероватно -{''[[Homo habilis]]''}-, су били нађени на локацијама у близини старости Гона алата.<ref>{{harvnb|Rogers|Semaw|2009|p=164}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Изум технике [[Топљење |топљења]] [[руда |руде]] означио је крај каменог доба и почетак [[Бронзано доба |бронзаног доба]]. The first most significant metal manufactured was [[bronze]], an alloy of copper and [[tin]], each of which was smelted separately. The transition from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age was a period during which modern people could smelt copper, but did not yet manufacture bronze, a time known as the [[Copper Age]], or more technically the [[Chalcolithic]], "copper-stone" age. The Chalcolithic by convention is the initial period of the Bronze Age. The Bronze Age was followed by the [[Iron Age]]. |

|||

The transition out of the Stone Age occurred between 6000 BCE and 2500 [[BCE]] for much of humanity living in [[North Africa]] and [[Eurasia]]. The first evidence of human [[metallurgy]] dates to between the [[5th millennium BC|5th]] and [[6th millennium BC|6th]] [[millennium]] BCE in the archaeological sites of [[Majdanpek]], [[Yarmovac]], and [[Pločnik]] in modern-day Serbia ([[Prokuplje#Archaeological findings|a copper axe from 5500 BCE]] belonging to the [[Vinca culture]]), though not conventionally considered part of the Chalcolithic or "Copper Age", this provides the earliest known example of copper metallurgy.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.stonepages.com/news/archives/002605.html | title=Neolithic Vinca was a metallurgical culture | date=17 November 2007 | publisher=Archaeo News | agency=Reuters | accessdate=25 January 2011}}</ref> Note the [[Rudna Glava]] mine in [[Serbia]]. [[Ötzi the Iceman]], a [[mummy]] from about 3300 BCE carried with him a copper axe and a flint knife. |

|||

In regions such as [[Sub-Saharan Africa]], the Stone Age was followed directly by the Iron Age.<ref>{{cite book|author1=S.J.S. Cookey|editor1-last=Swartz|editor1-first=B.K.|editor2-last=Dumett|editor2-first=Raymond E.|title=West African Culture Dynamics: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives|date=1980|publisher=Mouton de Gruyter|isbn=978-9027979209|page=329|url=https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8_Z5N0gmNlsC&pg=PA329&dq=africa+Stone+Age+was+followed+directly+by+the+iron+age&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiT_93oyIvNAhUK2hoKHdnpCi0Q6AEITzAI#v=onepage&q=africa%20Stone%20Age%20was%20followed%20directly%20by%20the%20iron%20age&f=false|accessdate=3 June 2016|chapter=An Ethnohistorical Reconstruction of Traditional Igbo Society}}</ref> The Middle East and [[southeast Asia|southeastern Asian]] regions progressed past Stone Age technology around 6000 BCE. Europe, and the rest of Asia became post–Stone Age societies by about 4000 BCE. The [[Cultural periods of Peru|proto-Inca]] cultures of South America continued at a Stone Age level until around 2000 BCE, when gold, copper and silver made their entrance. The Americas notably did not develop a widespread behavior of smelting Bronze or Iron after the Stone Age period, although the technology existed.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Easby|first1=Dudley T.|title=Pre-Hispanic Metallurgy and Metalworking in the New World|journal=Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society|date=April 1965|volume=109|issue=2|pages=89–98}}</ref> Stone tool manufacture continued even after the Stone Age ended in a given area. In Europe and North America, [[millstone]]s were in use until well into the 20th century, and still are in many parts of the world. |

|||

=== Концепт каменог доба === |

|||

The terms "Stone Age", "Bronze Age", and "Iron Age" were never meant to suggest that advancement and time periods in prehistory are only measured by the type of tool material, rather than, for example, [[social organization]], [[food sources]] exploited, adaptation to climate, adoption of agriculture, cooking, [[Human settlement|settlement]] and religion. Like [[pottery]], the typology of the stone tools combined with the relative sequence of the types in various regions provide a chronological framework for the evolution of man and society. They serve as diagnostics of date, rather than characterizing the people or the society. |

|||

[[Lithic analysis]] is a major and specialised form of archaeological investigation. It involves the measurement of the stone tools to determine their typology, function and the technology involved. It includes scientific study of the [[lithic reduction]] of the raw materials, examining how the artifacts were made. Much of this study takes place in the laboratory in the presence of various specialists. In [[experimental archaeology]], researchers attempt to create replica tools, to understand how they were made. [[Flintknapper]]s are craftsmen who use sharp tools to reduce [[flint]]stone to [[Flint (tool)|flint tool]]. |

|||

[[File:National park stone tools.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Разна [[Камено оруђе |камена оруђа]]]] |

|||

In addition to lithic analysis, the field prehistorian utilizes a wide range of techniques derived from multiple fields. The work of the archaeologist in determining the paleocontext and relative sequence of the layers is supplemented by the efforts of the geologic specialist in identifying layers of rock over geologic time, of the paleontological specialist in identifying bones and animals, of the palynologist in discovering and identifying plant species, of the physicist and chemist in laboratories determining dates by the [[carbon-14]], [[K–Ar dating|potassium-argon]] and other methods. Study of the Stone Age has never been mainly about stone tools and archaeology, which are only one form of evidence. The chief focus has always been on the society and the physical people who belonged to it. |

|||

Useful as it has been, the concept of the Stone Age has its limitations. The date range of this period is ambiguous, disputed, and variable according to the region in question. While it is possible to speak of a general 'stone age' period for the whole of humanity, some groups never developed metal-[[smelting]] technology, so remained in a 'stone age' until they encountered technologically developed cultures. The term was innovated to describe the [[archaeological culture]]s of Europe. It may not always be the best in relation to regions such as some parts of the [[Indies]] and Oceania, where [[farmers]] or [[hunter-gatherer]]s used stone for tools until European [[colonisation]] began. |

|||

The archaeologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries CE, who adapted the [[three-age system]] to their ideas, hoped to combine cultural anthropology and archaeology in such a way that a specific contemporaneous tribe can be used to illustrate the way of life and beliefs of the people exercising a specific Stone-Age technology. As a description of people living today, the term ''stone age'' is controversial. The [[Association of Social Anthropologists]] discourages this use, asserting:<ref>{{cite news | title=ASA Statement on the use of 'primitive' as a descriptor of contemporary human groups | newspaper=ASA News | date=27 August 2007 | publisher=Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth | url=http://www.theasa.org/news.shtml#asa}}</ref><blockquote>"To describe any living group as 'primitive' or 'Stone Age' inevitably implies that they are living representatives of some earlier stage of human development that the majority of humankind has left behind."</blockquote> |

|||

=== Троступни систем === |

|||

In the 1920s, South African archaeologists organizing the stone tool collections of that country observed that they did not fit the newly detailed Three-Age System. In the words of [[J. Desmond Clark]],<ref>{{harvnb|Clark|1970|p=22}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote> "It was early realized that the threefold division of culture into Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages adopted in the nineteenth century for Europe had no validity in Africa outside the Nile valley."</blockquote> |

|||

Consequently, they proposed a new system for Africa, the Three-stage System. Clark regarded the Three-age System as valid for North Africa; in sub-Saharan Africa, the Three-stage System was best.<ref>{{harvnb|Clark|1970|pp=18–19}}</ref> In practice, the failure of African archaeologists either to keep this distinction in mind, or to explain which one they mean, contributes to the considerable equivocation already present in the literature. There are in effect two Stone Ages, one part of the Three-age and the other constituting the Three-stage. They refer to one and the same artifacts and the same technologies, but vary by locality and time. |

|||

The three-stage system was proposed in 1929 by Astley John Hilary Goodwin, a professional archaeologist, and [[Clarence van Riet Lowe]], a civil engineer and amateur archaeologist, in an article titled "Stone Age Cultures of South Africa" in the journal ''Annals of the South African Museum''. By then, the dates of the Early Stone Age, or [[Paleolithic]], and Late Stone Age, or [[Neolithic]] (''neo'' = new), were fairly solid and were regarded by Goodwin as absolute. He therefore proposed a relative chronology of periods with floating dates, to be called the Earlier and Later Stone Age. The Middle Stone Age would not change its name, but it would not mean [[Mesolithic]].<ref>{{harvnb|Deacon|Deacon|1999|pp=5–6}}</ref> |

|||

The duo thus reinvented the Stone Age. In Sub-Saharan Africa, however, iron-working technologies were either invented independently or came across the Sahara from the north (see ''[[iron metallurgy in Africa]]''). The Neolithic was characterized primarily by herding societies rather than large agricultural societies, and although there was [[copper metallurgy in Africa]] as well as bronze smelting, archaeologists do not currently recognize a separate Copper Age or Bronze Age. Moreover, the technologies included in those 'stages', as Goodwin called them, were not exactly the same. Since then, the original relative terms have become identified with the technologies of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, so that they are no longer relative. Moreover, there has been a tendency to drop the comparative degree in favor of the positive: resulting in two sets of Early, Middle and Late Stone Ages of quite different content and chronologies. |

|||

By voluntary agreement, archaeologists respect the decisions of the Pan-African Congress of Prehistory, which meets every four years to resolve archaeological business brought before it. Delegates are actually international; the organization takes its name from the topic. [[Louis Leakey]] hosted the first one in [[Nairobi]] in 1947. It adopted Goodwin and Lowe's 3-stage system at that time, the stages to be called Early, Middle and Later. |

|||

=== Проблем транзиције === |

|||

The problem of the transitions in archaeology is a branch of the general philosophic continuity problem, which examines how discrete objects of any sort that are [[contiguity|contiguous]] in any way can be presumed to have a relationship of any sort. In archaeology, the relationship is one of [[causality]]. If Period B can be presumed to descend from Period A, there must be a boundary between A and B, the A–B boundary. The problem is in the nature of this boundary. If there is no distinct boundary, then the population of A suddenly stopped using the customs characteristic of A and suddenly started using those of B, an unlikely scenario in the process of [[evolution]]. More realistically, a distinct border period, the A/B transition, existed, in which the customs of A were gradually dropped and those of B acquired. If transitions do not exist, then there is no proof of any continuity between A and B. |

|||

The Stone Age of Europe is characteristically in deficit of known transitions. The 19th and early 20th-century innovators of the modern [[three-age system]] recognized the problem of the initial transition, the "gap" between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. [[Louis Leakey]] provided something of an answer by proving that man evolved in Africa. The Stone Age must have begun there to be carried repeatedly to Europe by migrant populations. The different phases of the Stone Age thus could appear there without transitions. The burden on African archaeologists became all the greater, because now they must find the missing transitions in Africa. The problem is difficult and ongoing. |

|||

After its adoption by the First Pan African Congress in 1947, the Three-Stage Chronology was amended by the Third Congress in 1955 to include a First Intermediate Period between Early and Middle, to encompass the [[Fauresmith (industry)|Fauresmith]] and [[Sangoan]] technologies, and the Second Intermediate Period between Middle and Later, to encompass the [[Magosian]] technology and others. The chronologic basis for definition was entirely relative. With the arrival of scientific means of finding an absolute chronology, the two intermediates turned out to be [[will-of-the-wisp]]s. They were in fact [[Middle Paleolithic|Middle]] and [[Lower Paleolithic]]. Fauresmith is now considered to be a [[facies]] of [[Acheulean]], while Sangoan is a facies of [[Lupemban]].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | first=Glynn | last=Isaac | authorlink=Glynn Isaac | title=The Earliest Archaeological Traces | editor-first=J. Desmond | series=Volume | editor-last=Clark | encyclopedia=The Cambridge History of Africa | volume=I: From the Earliest Times to C. 500 BC | page=246 | location=Cambridge | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1982 | ref=harv}}</ref> Magosian is "an artificial mix of two different periods."<ref>{{cite book | last=Willoughby | first=Pamela R. | year=2007 | title=The evolution of modern humans in Africa: a comprehensive guide | location=Lanham, Maryland | publisher=AltaMira Press | page=54}}</ref> |

|||

Once seriously questioned, the intermediates did not wait for the next Pan African Congress two years hence, but were officially rejected in 1965 (again on an advisory basis) by Burg Wartenstein Conference #29, ''Systematic Investigation of the African Later Tertiary and Quaternary'',<ref>{{harvnb|Barham|Mitchell|2008|p=477}}</ref> a conference in anthropology held by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, at Burg Wartenstein Castle, which it then owned in Austria, attended by the same scholars that attended the Pan African Congress, including Louis Leakey and [[Mary Leakey]], who was delivering a pilot presentation of her typological analysis of Early Stone Age tools, to be included in her 1971 contribution to ''Olduvai Gorge'', "Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960–1963."<ref>{{cite web | title=History: Systematic Investigation of the African Later Tertiary and Quaternary | url=http://wennergren.org/history/conferences-seminars-symposia/wenner-gren-symposia/cumulative-list-wenner-gren-symposia/we-23 | publisher=The Wenner-Gren Foundation | accessdate=3 March 2011}}</ref> |

|||

However, although the intermediate periods were gone, the search for the transitions continued. |

|||

== Референце == |

|||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

== Литература == |

== Литература == |

||

{{refbegin}} |

{{refbegin}} |

||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | first=Lawrence | last=Barham | first2=Peter | last2=Mitchell | title=The First Africans: African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers | year=2008 | location=Oxford | publisher=Oxford University Press | series=Cambridge World Archaeology}} |

|||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | first=Miriam | last=Belmaker | title=Community Structure through Time: 'Ubeidiya, a Lower Pleistocene Site as a Case Study (Thesis) |date=March 2006 | publisher=Paleoanthropology Society | url=http://www.paleoanthro.org/dissertations/Miriam%20Belmaker.pdf}} |

|||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | first=J. Desmond | last=Clark | title=The Prehistory of Africa | series=Ancient People and Places, Volume 72 | location=New York; Washington | publisher=Praeger Publishers | year=1970}} |

* {{cite book | ref=harv | first=J. Desmond | last=Clark | title=The Prehistory of Africa | series=Ancient People and Places, Volume 72 | location=New York; Washington | publisher=Praeger Publishers | year=1970}} |

||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | last=Deacon | first=Hilary John | first2=Janette | last2=Deacon | year=1999 | title=Human beginnings in South Africa: uncovering the secrets of the Stone Age | location=Walnut Creek, |

* {{cite book | ref=harv | last=Deacon | first=Hilary John | first2=Janette | last2=Deacon | year=1999 | title=Human beginnings in South Africa: uncovering the secrets of the Stone Age | location=Walnut Creek, California [u.a.] | publisher=Altamira Press}} |

||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | first=Salvatore | last=Piccolo | title=Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily | location=Thornham/Norfolk (UK)| publisher=Brazen Head Publishing | year=2013}} |

* {{cite book | ref=harv | first=Salvatore | last=Piccolo | title=Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily | location=Thornham/Norfolk (UK)| publisher=Brazen Head Publishing | year=2013}} |

||

* {{Cite book | ref=harv |editor-last=Camps |

* {{Cite book | ref=harv |editor-last=Camps Calbet |editor-first=Marta | editor2-first=Parth R. | editor2-last=Chauhan |year=2009 | title=Sourcebook of paleolithic transitions: methods, theories, and interpretations | location=New York | publisher=Springer |first=Michael J. | last=Rogers | first2=Sileshi | last2=Semaw | contribution=From Nothing to Something: The Appearance and Context of the Earliest Archaeological Record}} |

||

* {{Cite book | ref=harv | first=John J. | last=Shea | |

* {{Cite book| ref=harv |last=Schick|first=Kathy D.|first2=Nicholas|last2= Toth|title=Making Silent Stones Speak: Human Evolution and the Dawn of Technology|publisher=Simon & Schuster|location=New York|year=1993|isbn=0-671-69371-9}} |

||

* {{Cite book | ref=harv | first=John J. | last=Shea | others= Stone Age Visiting Cards Revisited: a Strategic Perspective on the Lithic Technology of Early Hominin Dispersal | pages=47–64 | editor-first=John G. | editor-last=Fleagle | editor2-first=John J. | editor2-last=Shea | editor3-first=Frederick E. | editor3-last=Grine | editor4-first=Andrea L. | editor4-last=Boden | editor5-first=Richard E, | editor5-last=Leakey | title=Out of Africa I: the First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia | year=2010 | location=Dordrecht; Heidelberg; London; New York | publisher=Springer}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Scarre|first=Christopher |year=1988|title=Past Worlds: The Times Atlas of Archaeology|publisher=Times Books|location=London|isbn=0-7230-0306-8}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Commonscat|Stone Age}} |

{{Commonscat|Stone Age}} |

||

* [http://history-world.org/stone_age.htm Камено доба] {{ен}} |

* [http://history-world.org/stone_age.htm Камено доба] {{ен}} |

||

* {{cite web | title=The Stone Age | url=http://history-world.org/stone_age.htm | first=Robert A. | last=Giusepi | year=2000 | publisher=History World International | accessdate=22 February 2011}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title=Stone Age Hand-axes | url=http://www.aerobiologicalengineering.com/wxk116/StoneAge/Handaxes/ | first=D.R. | last=Kowalski | publisher=AerobiologicalEngineering.com | accessdate=22 February 2011}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title=Stone Age Habitats |url=http://www.aerobiologicalengineering.com/wxk116/StoneAge/Habitats/ | first=D.R. | last=Kowalski | publisher=AerobiologicalEngineering.com | accessdate=22 February 2011}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title=PanAfrican Archaeological Association | url=http://www.panafprehistory.org/index.php/ | accessdate=28 February 2011}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title=Society of Africanist Archaeologists | url=http://www.safa.rice.edu/ | accessdate=3 March 2011}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title=The ASA | url=http://www.theasa.org/ | publisher=Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth}} |

|||

* -{[http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-evolution-timeline-interactive Human Timeline (Interactive)] – [[Smithsonian Institution|Smithsonian]], [[National Museum of Natural History]] (August 2016).}- |

|||

{{Доба}} |

{{Доба}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Категорија:Археологија]] |

[[Категорија:Археологија]] |

||

Верзија на датум 4. октобар 2017. у 06:01

- За више детаља о трипериодном систему епоха види и Метално доба

| Део серије о људској историји и преисторији |

| Људска историја и преисторија |

|---|

| ↑ пре рода Homo (плиоцен) |

|

Преисторија (трипериодни систем) |

| Забележена историја |

| ↓ Будућност (холоцен) |

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Камено доба означава најстарије раздобље праисторије. Прву периодизацију праисторије дефинисао је дански археолог Кристијан Томасен 1836. године. Његов „тропериодни систем“ којим се праисторија дели на камено, бронзано и гвоздено доба постаје темељем свих каснијих периодизација. Назив је добило по камену од ког су претежно израђивани алати. Камено доба је широк преисторијски период током кога је камен био у широкој употреби за прављење оруђа са ивицом или врхом. Овај период је трајао око 3,4 милиона година[1] и завшио се између 8700 п. н. е. и 2000 п. н. е. са развојом обраде метала.

Године 1865. британски археолог Џон Лубок камено доба дели на старије камено доба или палеолит и млађе камено доба или неолит. Године 1866. Вентроп је додао средње камено доба или мезолит.

Историјски значај

Камено доба се подудара са еволуцијом рода Homo. Једини могући изузетак је рано камено доба, током кога је могуће да су врсте које су претходиле врсти Homo производиле оруђе.[2] Судећи по добу и локацији постојеће евиденције, колевка људског рода је био систем Источно Афричког расцепа, посебно предео севера Етиопије, где се граничи са пашњацима. Најближи сродник међу другим живућим приматима, род Pan, представља грану која је наставила да обитава у дубокој шуми, где су примати еволуирали. Расцеп је служио као пролаз за кретање у јужну Африку а исто тако северно низ Нил у сверну Африку и кроз натавак процепа до Леванта и на огромне травњаке Азије.

Почевши пре око 4 милиона година (mya) један биом се успоставио од Јужне Африке кроз процеп, северну Африку, и кроз Азију до модерне Кине, који се назива „трансконтинентални 'саванастан'”.[3] Полазећи од пашњака у процепу, Homo erectus, претходник савремених људи, је нашао еколошку нишу као градитељ алата и временом је развио зависност од тога, постајући „оруђима опремљен становник саване”.[4]

Камено доба у археологији

Почетак каменог доба

Најстарија посредна евиденција о употреби каменог оруђа су фосилизоване животињске кости са трагом употребе алата; оне су око 3,4 милиона годна старе и нађене су у долини Аваш у Етиопији.[1] Археолошка открића у Кенији из 2015, указују на могућност да је то могућа најстарија хоминидна употреба оруђа до данас позната, из чега следи да је Kenyanthropus platyops (3,2 до 3,5 милиона година стар плиоценски хоминински фосил откривен на језеру Туркана у Кенији 1999. године) вероватно био најранији познати корисник оруђа.[5]

Најстарија камена оруђа су ископана на локацији Ломекви 3 у западној Туркани у северзападној Кенији, и стара су око 3,3 милиона година.[6] Пре открића тих „Ломеквијанских” оруђа, најстарија позната оруђа су била нађена на неколико локација у Гони, Етиопија, у седиментима палео-Авашке реке, који су помогли у њиховом датирању. Сва та оруђа птичу из Бусидамске формације, која лежи изнад дисконформитета, или недостајућег слоја, који одговара периоду од пре 2,9 до 2,7 милиона година. Најстарије локације које садрже оруђа су датиране на пре 2,6–2,55 милиона година.[7] Једна од најупечатљивијих околности ових локација је да су оне из касног плиоцена, док се пре њиховог открића сматрало да су алати еволуирали само у плеистоцену. Екскаватори на локалитету напомињу да су:[8]

- "... најранији израђивачи камених оруђа били вешти окресивачи .... Могући разлози иза овог наизглед наглог преласка из одсуства камених алата на његово присуство укључују ... празнине у геолошком запису."

Врсте које су направиле плиоценска оруђа нису познате. Фрагменти Australopithecus garhi, Australopithecus aethiopicus[9] и Homo, вероватно Homo habilis, су били нађени на локацијама у близини старости Гона алата.[10]

Крај каменог доба

Изум технике топљења руде означио је крај каменог доба и почетак бронзаног доба. The first most significant metal manufactured was bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, each of which was smelted separately. The transition from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age was a period during which modern people could smelt copper, but did not yet manufacture bronze, a time known as the Copper Age, or more technically the Chalcolithic, "copper-stone" age. The Chalcolithic by convention is the initial period of the Bronze Age. The Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age.

The transition out of the Stone Age occurred between 6000 BCE and 2500 BCE for much of humanity living in North Africa and Eurasia. The first evidence of human metallurgy dates to between the 5th and 6th millennium BCE in the archaeological sites of Majdanpek, Yarmovac, and Pločnik in modern-day Serbia (a copper axe from 5500 BCE belonging to the Vinca culture), though not conventionally considered part of the Chalcolithic or "Copper Age", this provides the earliest known example of copper metallurgy.[11] Note the Rudna Glava mine in Serbia. Ötzi the Iceman, a mummy from about 3300 BCE carried with him a copper axe and a flint knife.

In regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, the Stone Age was followed directly by the Iron Age.[12] The Middle East and southeastern Asian regions progressed past Stone Age technology around 6000 BCE. Europe, and the rest of Asia became post–Stone Age societies by about 4000 BCE. The proto-Inca cultures of South America continued at a Stone Age level until around 2000 BCE, when gold, copper and silver made their entrance. The Americas notably did not develop a widespread behavior of smelting Bronze or Iron after the Stone Age period, although the technology existed.[13] Stone tool manufacture continued even after the Stone Age ended in a given area. In Europe and North America, millstones were in use until well into the 20th century, and still are in many parts of the world.

Концепт каменог доба

The terms "Stone Age", "Bronze Age", and "Iron Age" were never meant to suggest that advancement and time periods in prehistory are only measured by the type of tool material, rather than, for example, social organization, food sources exploited, adaptation to climate, adoption of agriculture, cooking, settlement and religion. Like pottery, the typology of the stone tools combined with the relative sequence of the types in various regions provide a chronological framework for the evolution of man and society. They serve as diagnostics of date, rather than characterizing the people or the society.

Lithic analysis is a major and specialised form of archaeological investigation. It involves the measurement of the stone tools to determine their typology, function and the technology involved. It includes scientific study of the lithic reduction of the raw materials, examining how the artifacts were made. Much of this study takes place in the laboratory in the presence of various specialists. In experimental archaeology, researchers attempt to create replica tools, to understand how they were made. Flintknappers are craftsmen who use sharp tools to reduce flintstone to flint tool.

In addition to lithic analysis, the field prehistorian utilizes a wide range of techniques derived from multiple fields. The work of the archaeologist in determining the paleocontext and relative sequence of the layers is supplemented by the efforts of the geologic specialist in identifying layers of rock over geologic time, of the paleontological specialist in identifying bones and animals, of the palynologist in discovering and identifying plant species, of the physicist and chemist in laboratories determining dates by the carbon-14, potassium-argon and other methods. Study of the Stone Age has never been mainly about stone tools and archaeology, which are only one form of evidence. The chief focus has always been on the society and the physical people who belonged to it.

Useful as it has been, the concept of the Stone Age has its limitations. The date range of this period is ambiguous, disputed, and variable according to the region in question. While it is possible to speak of a general 'stone age' period for the whole of humanity, some groups never developed metal-smelting technology, so remained in a 'stone age' until they encountered technologically developed cultures. The term was innovated to describe the archaeological cultures of Europe. It may not always be the best in relation to regions such as some parts of the Indies and Oceania, where farmers or hunter-gatherers used stone for tools until European colonisation began.

The archaeologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries CE, who adapted the three-age system to their ideas, hoped to combine cultural anthropology and archaeology in such a way that a specific contemporaneous tribe can be used to illustrate the way of life and beliefs of the people exercising a specific Stone-Age technology. As a description of people living today, the term stone age is controversial. The Association of Social Anthropologists discourages this use, asserting:[14]

"To describe any living group as 'primitive' or 'Stone Age' inevitably implies that they are living representatives of some earlier stage of human development that the majority of humankind has left behind."

Троступни систем

In the 1920s, South African archaeologists organizing the stone tool collections of that country observed that they did not fit the newly detailed Three-Age System. In the words of J. Desmond Clark,[15]

"It was early realized that the threefold division of culture into Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages adopted in the nineteenth century for Europe had no validity in Africa outside the Nile valley."

Consequently, they proposed a new system for Africa, the Three-stage System. Clark regarded the Three-age System as valid for North Africa; in sub-Saharan Africa, the Three-stage System was best.[16] In practice, the failure of African archaeologists either to keep this distinction in mind, or to explain which one they mean, contributes to the considerable equivocation already present in the literature. There are in effect two Stone Ages, one part of the Three-age and the other constituting the Three-stage. They refer to one and the same artifacts and the same technologies, but vary by locality and time.

The three-stage system was proposed in 1929 by Astley John Hilary Goodwin, a professional archaeologist, and Clarence van Riet Lowe, a civil engineer and amateur archaeologist, in an article titled "Stone Age Cultures of South Africa" in the journal Annals of the South African Museum. By then, the dates of the Early Stone Age, or Paleolithic, and Late Stone Age, or Neolithic (neo = new), were fairly solid and were regarded by Goodwin as absolute. He therefore proposed a relative chronology of periods with floating dates, to be called the Earlier and Later Stone Age. The Middle Stone Age would not change its name, but it would not mean Mesolithic.[17]

The duo thus reinvented the Stone Age. In Sub-Saharan Africa, however, iron-working technologies were either invented independently or came across the Sahara from the north (see iron metallurgy in Africa). The Neolithic was characterized primarily by herding societies rather than large agricultural societies, and although there was copper metallurgy in Africa as well as bronze smelting, archaeologists do not currently recognize a separate Copper Age or Bronze Age. Moreover, the technologies included in those 'stages', as Goodwin called them, were not exactly the same. Since then, the original relative terms have become identified with the technologies of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, so that they are no longer relative. Moreover, there has been a tendency to drop the comparative degree in favor of the positive: resulting in two sets of Early, Middle and Late Stone Ages of quite different content and chronologies.

By voluntary agreement, archaeologists respect the decisions of the Pan-African Congress of Prehistory, which meets every four years to resolve archaeological business brought before it. Delegates are actually international; the organization takes its name from the topic. Louis Leakey hosted the first one in Nairobi in 1947. It adopted Goodwin and Lowe's 3-stage system at that time, the stages to be called Early, Middle and Later.

Проблем транзиције

The problem of the transitions in archaeology is a branch of the general philosophic continuity problem, which examines how discrete objects of any sort that are contiguous in any way can be presumed to have a relationship of any sort. In archaeology, the relationship is one of causality. If Period B can be presumed to descend from Period A, there must be a boundary between A and B, the A–B boundary. The problem is in the nature of this boundary. If there is no distinct boundary, then the population of A suddenly stopped using the customs characteristic of A and suddenly started using those of B, an unlikely scenario in the process of evolution. More realistically, a distinct border period, the A/B transition, existed, in which the customs of A were gradually dropped and those of B acquired. If transitions do not exist, then there is no proof of any continuity between A and B.

The Stone Age of Europe is characteristically in deficit of known transitions. The 19th and early 20th-century innovators of the modern three-age system recognized the problem of the initial transition, the "gap" between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. Louis Leakey provided something of an answer by proving that man evolved in Africa. The Stone Age must have begun there to be carried repeatedly to Europe by migrant populations. The different phases of the Stone Age thus could appear there without transitions. The burden on African archaeologists became all the greater, because now they must find the missing transitions in Africa. The problem is difficult and ongoing.

After its adoption by the First Pan African Congress in 1947, the Three-Stage Chronology was amended by the Third Congress in 1955 to include a First Intermediate Period between Early and Middle, to encompass the Fauresmith and Sangoan technologies, and the Second Intermediate Period between Middle and Later, to encompass the Magosian technology and others. The chronologic basis for definition was entirely relative. With the arrival of scientific means of finding an absolute chronology, the two intermediates turned out to be will-of-the-wisps. They were in fact Middle and Lower Paleolithic. Fauresmith is now considered to be a facies of Acheulean, while Sangoan is a facies of Lupemban.[18] Magosian is "an artificial mix of two different periods."[19]

Once seriously questioned, the intermediates did not wait for the next Pan African Congress two years hence, but were officially rejected in 1965 (again on an advisory basis) by Burg Wartenstein Conference #29, Systematic Investigation of the African Later Tertiary and Quaternary,[20] a conference in anthropology held by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, at Burg Wartenstein Castle, which it then owned in Austria, attended by the same scholars that attended the Pan African Congress, including Louis Leakey and Mary Leakey, who was delivering a pilot presentation of her typological analysis of Early Stone Age tools, to be included in her 1971 contribution to Olduvai Gorge, "Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960–1963."[21]

However, although the intermediate periods were gone, the search for the transitions continued.

Референце

- ^ а б https://web.archive.org/web/20100818123718/http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2010/august/oldest-tool-use-and-meat-eating-revealed75831.html

- ^ Ko, Kwang Hyun (2016). „Origins of human intelligence: The chain of tool-making and brain evolution” (PDF). Anthropological Notebooks. 22 (1): 5—22.

- ^ Barham & Mitchell 2008, стр. 106

- ^ Barham & Mitchell 2008, стр. 147

- ^ BBC News, 21/05/2015: Oldest stone tools pre-date earliest humans

- ^ Harmand, Sonia; et al. (21. 5. 2015). „3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya”. Nature. 521: 310—315. PMID 25993961. doi:10.1038/nature14464.

- ^ Rogers & Semaw 2009, стр. 162–163

- ^ Rogers & Semaw 2009, стр. 155

- ^ As to whether aethiopicus is the genus Australopithecus or the genus Paranthropus, broken out to include the more robust forms, anthropological opinion is divided and both usages occur in the professional sources.

- ^ Rogers & Semaw 2009, стр. 164

- ^ „Neolithic Vinca was a metallurgical culture”. Archaeo News. Reuters. 17. 11. 2007. Приступљено 25. 1. 2011.

- ^ S.J.S. Cookey (1980). „An Ethnohistorical Reconstruction of Traditional Igbo Society”. Ур.: Swartz, B.K.; Dumett, Raymond E. West African Culture Dynamics: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives. Mouton de Gruyter. стр. 329. ISBN 978-9027979209. Приступљено 3. 6. 2016.

- ^ Easby, Dudley T. (април 1965). „Pre-Hispanic Metallurgy and Metalworking in the New World”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 109 (2): 89—98.

- ^ „ASA Statement on the use of 'primitive' as a descriptor of contemporary human groups”. ASA News. Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth. 27. 8. 2007.

- ^ Clark 1970, стр. 22

- ^ Clark 1970, стр. 18–19

- ^ Deacon & Deacon 1999, стр. 5–6

- ^ Isaac, Glynn (1982). „The Earliest Archaeological Traces”. Ур.: Clark, J. Desmond. The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume. I: From the Earliest Times to C. 500 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. стр. 246.

- ^ Willoughby, Pamela R. (2007). The evolution of modern humans in Africa: a comprehensive guide. Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press. стр. 54.

- ^ Barham & Mitchell 2008, стр. 477

- ^ „History: Systematic Investigation of the African Later Tertiary and Quaternary”. The Wenner-Gren Foundation. Приступљено 3. 3. 2011.

Литература

- Barham, Lawrence; Mitchell, Peter (2008). The First Africans: African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers. Cambridge World Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Belmaker, Miriam (март 2006). Community Structure through Time: 'Ubeidiya, a Lower Pleistocene Site as a Case Study (Thesis) (PDF). Paleoanthropology Society.

- Clark, J. Desmond (1970). The Prehistory of Africa. Ancient People and Places, Volume 72. New York; Washington: Praeger Publishers.

- Deacon, Hilary John; Deacon, Janette (1999). Human beginnings in South Africa: uncovering the secrets of the Stone Age. Walnut Creek, California [u.a.]: Altamira Press.

- Piccolo, Salvatore (2013). Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily. Thornham/Norfolk (UK): Brazen Head Publishing.

- Rogers, Michael J.; Semaw, Sileshi (2009). „From Nothing to Something: The Appearance and Context of the Earliest Archaeological Record”. Ур.: Camps Calbet, Marta; Chauhan, Parth R. Sourcebook of paleolithic transitions: methods, theories, and interpretations. New York: Springer.

- Schick, Kathy D.; Toth, Nicholas (1993). Making Silent Stones Speak: Human Evolution and the Dawn of Technology. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-69371-9.

- Shea, John J. (2010). Fleagle, John G.; Shea, John J.; Grine, Frederick E.; Boden, Andrea L.; Leakey, Richard E,, ур. Out of Africa I: the First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia. Stone Age Visiting Cards Revisited: a Strategic Perspective on the Lithic Technology of Early Hominin Dispersal. Dordrecht; Heidelberg; London; New York: Springer. стр. 47—64.

- Scarre, Christopher (1988). Past Worlds: The Times Atlas of Archaeology. London: Times Books. ISBN 0-7230-0306-8.

Спољашње везе

- Камено доба (језик: енглески)

- Giusepi, Robert A. (2000). „The Stone Age”. History World International. Приступљено 22. 2. 2011.

- Kowalski, D.R. „Stone Age Hand-axes”. AerobiologicalEngineering.com. Приступљено 22. 2. 2011.

- Kowalski, D.R. „Stone Age Habitats”. AerobiologicalEngineering.com. Приступљено 22. 2. 2011.

- „PanAfrican Archaeological Association”. Приступљено 28. 2. 2011.

- „Society of Africanist Archaeologists”. Приступљено 3. 3. 2011.

- „The ASA”. Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).