Вештачка интелигенција — разлика између измена

м Dcirovic преместио је страницу Вјештачка интелигенција на Вештачка интелигенција преко преусмерења: . |

. ознака: везе до вишезначних одредница |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{short description|Интелигенција машина или софтвера}}{{рут}} |

|||

[[Датотека:HONDA ASIMO.jpg|мини|десно|200п|Хондин интелигентни хуманоидни робот [[АСИМО]]]] |

|||

[[Датотека:HONDA ASIMO.jpg|мини|десно|200п|Хондин интелигентни хуманоидни робот [[ASIMO]]]] |

|||

'''Вјештачка интелигенција''' (такође VI) је подобласт [[рачунарство|рачунарства]]. Циљ истраживања вјештачке интелигенције је развијање програма ([[софтвер]]а), који ће рачунарима омогућити да се понашају на начин који би се могао окарактерисати интелигентним. Прва истраживања се вежу за саме коријене рачунарства. Идеја о стварању машина које ће бити способне да обављају различите задатке интелигентно, била је централна преокупација научника рачунарства који су се опредијелили за истраживање вјештачке интелигенције, током цијеле друге половине [[20. век|20. вијека]]. Савремена истраживања у вјештачкој интелигенцији су оријентисана на [[експертски системи|експертске]] и преводилачке системе у ограниченим доменима, препознавање природног говора и писаног текста, [[аутоматски доказивач теорема|аутоматске доказиваче теорема]], као и константно интересовање за стварање генерално интелигентних [[аутономни агенти|аутономних агената]]. |

|||

'''Вештачка интелигенција''' (такође VI) је подобласт [[рачунарство|рачунарства]] која развија и проучава интелигентне машине.<ref>{{Cite book | first1 = Stuart J. | last1 = Russell | author1-link = Stuart J. Russell | first2 = Peter. | last2 = Norvig | author2-link = Peter Norvig | title=[[Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach]] | year = 2021 | edition = 4th | isbn = 978-0134610993 | lccn = 20190474 | publisher = Pearson | location = Hoboken }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | first1 = Elaine | last1 = Rich | author1-link = Elaine Rich | first2 = Kevin | last2 = Knight | first3 = Shivashankar B | last3 = Nair | title = Artificial Intelligence | date = 2010 | isbn = 978-0070087705 | language = en | publisher = Tata McGraw Hill India | location = New Delhi | edition = 3rd }}</ref> Вештачка интелигенција је интелигенција [[машина]] или софтвера, за разлику од интелигенције живих бића, првенствено [[Human intelligence|људи]]. Циљ истраживања вештачке интелигенције је развијање програма ([[софтвер]]а), који ће рачунарима омогућити да се понашају на начин који би се могао окарактерисати интелигентним. Прва истраживања се вежу за саме корене рачунарства. Идеја о стварању машина које ће бити способне да обављају различите задатке интелигентно, била је централна преокупација научника рачунарства који су се определили за истраживање вештачке интелигенције, током целе друге половине [[20. век]]а. Савремена истраживања у вештачкој интелигенцији су оријентисана на [[експертски системи|експертске]] и преводилачке системе у ограниченим доменима, препознавање природног говора и писаног текста, [[аутоматски доказивач теорема|аутоматске доказиваче теорема]], као и константно интересовање за стварање генерално интелигентних [[аутономни агенти|аутономних агената]]. Вештачка интелигенција као појам у ширем смислу, означава капацитет једне вештачке творевине за реализовање функција које су карактеристика људског размишљања. Могућност развоја сличне творевине је будила интересовање људи још од античког доба; ипак, тек у другој половини [[XX vek|XX века]] таква могућност је добила прва оруђа ([[рачунар]]е), чиме се отворио пут за тај подухват.<ref>[http://library.thinkquest.org/2705/ Artificial Intelligence] {{Wayback|url=http://library.thinkquest.org/2705/ |date=20110221055830 }}, Приступљено 28. 3. 2013.</ref> Потпомогнута напретком модерне науке, истраживања на пољу вештачке интелигенције се развијају у два основна смера: [[психологија|психолошка]] и [[физиологија|физиолошка]] истраживања природе људског ума, и технолошки развој све сложенијих [[рачунарство|рачунарских]] система. У том смислу, појам вештачке интелигенције се првобитно приписао системима и [[рачунарски програм|рачунарским програмима]] са способностима реализовања сложених задатака, односно симулацијама функционисања људског размишљања, иако и дан данас, прилично далеко од циља. У тој сфери, најважније области истраживања су обрада података, препознавање модела различитих области знања, игре и примијењене области, као на пример [[медицина]]. [[Applications of artificial intelligence|AI технологија]] се широко користи у [[Вештачка интелигенција у индустрији|индустрији]], [[Artificial intelligence in government|влади]] и науци. Неке апликације високог профила су: напредни [[web search engine|веб претраживачи]] (нпр. [[Google Search|Гоогле претрага]]), [[Sistemi za preporuku|системи препорука]] (које користе [[YouTube]], [[Amazon (company)|Амазон]] и [[Netflix|Нетфликс]]), интеракција путем [[natural-language understanding|људског говора]] (нпр. [[Google помоћник|Гугл асистант]], [[Сири]] и [[Amazon Alexa|Алекса]]), [[self-driving car|самостална вожња]] аутомобиле (нпр. [[Waymo|Вејмо]]), [[Generative artificial intelligence|генеративни]] и [[Computational creativity|креативни]] алати (нпр. [[ChatGPT]] и [[AI art|AI уметност]]), и надљудска игру и анализа у [[strategy game|стратешким играма]] (нпр. [[шах]] и [[Go (game)|го]]).{{sfnp|Google|2016}} |

|||

Вјештачка интелигенција као појам у ширем смислу, означава капацитет једне вјештачке творевине за реализовање функција које су карактеристика људског размишљања. Могућност развоја сличне творевине је будила интересовање људи још од античког доба ; ипак, тек у другој половини [[XX vek|XX вијека]] таква могућност је добила прва оруђа ([[рачунар]]е), чиме се отворио пут за тај подухват.<ref>[http://library.thinkquest.org/2705/ Artificial Intelligence] {{Wayback|url=http://library.thinkquest.org/2705/ |date=20110221055830 }}, Приступљено 28. 3. 2013.</ref> |

|||

Неке области данашњих истраживања обрађивања података се концентришу на програме који настоје оспособити рачунар за разумевање писане и вербалне информације, стварање резимеа, давање одговара на одређена питања или редистрибуцију података корисницима заинтересованим за одређене делове тих информација. У тим програмима је од суштинског значаја капацитет система за конструисање [[граматика|граматички]] коректних реченица и успостављање везе између речи и идеја, односно идентификовање значења. Истраживања су показала да, док је проблеме структурне [[логика|логике]] [[језик]]а, односно његове [[синтакса|синтаксе]], могуће решити [[програмски језик|програмирањем]] одговарајућих [[алгоритам]]а, проблем значења, или [[семантика]], је много дубљи и иде у правцу аутентичне вештачке интелигенције. Основне тенденције данас, за развој система VI представљају: развој [[експертски системи|експертских система]] и развој [[неуронска мрежа|неуронских мрежа]]. Експертски системи покушавају репродуковати људско размишљање преко [[симбол]]а. Неуронске мреже то раде више из [[биологија|биолошке]] перспективе (рекреирају структуру људског мозга уз помоћ [[генетски алгоритам|генетских алгоритама]]). Упркос сложености оба система, резултати су веома далеко од стварног интелигентног размишљања. Многи научници су скептици према могућности развијања истинске VI. Функционисање људског размишљања, још увек није дубље познато, из ког разлога ће [[информатички дизајн]] интелигентних система, још дужи временски период бити у суштини онеспособљен за представљање тих непознатих и сложених процеса. Истраживања у VI су фокусирана на следеће компоненте интелигенције: учење, размишљање, решавање проблема, перцепција и разумијевање природног језика. |

|||

Потпомогнута напретком модерне науке, истраживања на пољу вјештачке интелигенције се развијају у два основна смјера: [[психологија|психолошка]] и [[физиологија|физиолошка]] истраживања природе људског ума, и технолошки развој све сложенијих [[рачунарство|рачунарских]] система. |

|||

[[Алан Тјуринг]] је био прва особа која је спровела значајна истраживања у области коју је назвао машинска интелигенција.<ref name="turing"/> Вештачка интелигенција је основана као академска дисциплина 1956. године.<ref name="Dartmouth workshop"/> Поље је прошло кроз више циклуса оптимизма,<ref name="AI in the 60s"/><ref name="AI in the 80s"/> праћених периодима разочарења и губитка финансирања, познатим као [[AI winter|AI зима]].<ref name="First AI winter" /><ref name="Second AI winter"/> Финансирање и интересовање су се знатно повећали након 2012. када је [[deep learning|дубоко учење]] надмашило све претходне технике вештачке интелигенције,<ref name="Deep learning revolution"/> и после 2017. са архитектуром [[Transformer (machine learning model)|трансформатора]].{{sfnp|Toews|2023}} Ово је довело до [[AI spring|AI пролећа]] почетком 2020-их, при чему су компаније, универзитети и лабораторије које су претежно са седиштем у Сједињеним Државама, остварили значајне пионирске [[advances in artificial intelligence|напретке]] у вештачкој интелигенцији.{{sfnp|Frank|2023}} Све већа употреба вештачке интелигенције у 21. веку утиче на [[AI era|друштвени и економски помак]] ка повећању [[automation|аутоматизације]], [[data-driven decision-making|доношења одлука заснованих на подацима]] и [[Artificial intelligence systems integration|интеграцији AI система]] у различите економске секторе и области живота, утичући на [[Workplace impact of artificial intelligence|тржишта рада]], [[Artificial intelligence in healthcare|здравство]], владу , индустрија и [[Artificial intelligence in education|образовање]]. Ово поставља питања о [[Etika veštačke inteligencije|етичким импликацијама]] и [[AI risk|ризицима од AI]], што подстиче дискусије о [[Regulation of artificial intelligence|регулаторним политикама]] како би се осигурала [[AI safety|безбедност и предности]] технологије. Различите подобласти AI истраживања су усредсређене на одређене циљеве и употребу специфичних алата. Традиционални циљеви истраживања вештачке интелигенције обухватају [[Аутоматско резоновање|расуђивање]], [[knowledge representation|представљање знања]], [[Automated planning and scheduling|планирање]], [[machine learning|учење]], [[natural language processing|обрада природног језика]], [[machine perception|перцепција]] и подршка [[robotics|роботици]].{{efn|name="Problems of AI"}} [[Artificial general intelligence|Општа интелигенција]] (способност да се обави било који задатак који човек може да изврши) спада у дугорочне цињеве у овој области.<ref name="AGI"/> Да би решили ове проблеме, истраживачи вештачке интелигенције су прилагодили и интегрисали широк спектар техника решавања проблема, укључујући [[state space search|претрагу]] и [[mathematical optimization|математичку оптимизацију]], формалну логику, [[artificial neural network|вештачке неуронске мреже]] и методе засноване на [[statistics|статистици]], [[operations research|операционом истраживању]] и [[economics|економији]].{{efn|name="Tools of AI"}} AI се такође ослања на [[psychology|психологију]], [[linguistics|лингвистику]], [[philosophy|филозофију]], [[neuroscience|неуронауку]] и друге области.<ref name="AI influences">{{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§1.2}}.</ref> |

|||

У том смислу, појам вјештачке интелигенције се првобитно приписао системима и [[рачунарски програм|рачунарским програмима]] са способностима реализовања сложених задатака, односно симулацијама функционисања људског размишљања, иако и дан данас, прилично далеко од циља. У тој сфери, најважније области истраживања су обрада података, препознавање модела различитих области знања, игре и примијењене области, као на примјер [[медицина]]. |

|||

== Циљеви == |

|||

Неке области данашњих истраживања обрађивања података се концентришу на програме који настоје оспособити рачунар за разумијевање писане и вербалне информације, стварање резимеа, давање одговара на одређена питања или редистрибуцију података корисницима заинтересованим за одређене дијелове тих информација. У тим програмима је од суштинског значаја капацитет система за конструисање [[граматика|граматички]] коректних реченица и успостављање везе између ријечи и идеја, односно идентификовање значења. Истраживања су показала да, док је проблеме структурне [[логика|логике]] [[језик]]а, односно његове [[синтакса|синтаксе]], могуће ријешити [[програмски језик|програмирањем]] одговарајућих [[алгоритам]]а, проблем значења, или [[семантика]], је много дубљи и иде у правцу аутентичне вјештачке интелигенције. |

|||

Општи проблем симулације (или стварања) интелигенције подељен је на подпроблеме. Они се састоје од одређених особина или способности које истраживачи очекују да интелигентни систем покаже. Испод описане особине су задобиле највише пажње и покривају обим истраживања вештачке интелигенције.{{efn|name="Problems of AI"|Ова листа интелигентних особина заснована је на темама које покривају главни AI уџбеници, укључујући: {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021}}, {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004}}, {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998}} and {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998}}}} |

|||

Основне тенденције данас, за развој система VI представљају: развој [[експертски системи|експертских система]] и развој [[неуронска мрежа|неуронских мрежа]]. Експертски системи покушавају репродуковати људско размишљање преко [[симбол]]а. Неуронске мреже то раде више из [[биологија|биолошке]] перспективе (рекреирају структуру људског мозга уз помоћ [[генетски алгоритам|генетских алгоритама]]). Упркос сложености оба система, резултати су веома далеко од стварног интелигентног размишљања. |

|||

=== Основни циљеви истраживања на пољу вештачке интелигенције === |

|||

Многи научници су скептици према могућности развијања истинске VI. Функционисање људског размишљања, још увијек није дубље познато, из ког разлога ће [[информатички дизајн]] интелигентних система, још дужи временски период бити у суштини онеспособљен за представљање тих непознатих и сложених процеса. |

|||

Тренутно, када су у питању истраживања на пољу вештачке интелигенције, могуће је постићи два комплементарна циља, који респективно наглашавају два аспекта вештачке интелигенције, а то су теоријски и технолошки аспект. |

|||

Истраживања у VI су фокусирана на сљедеће компоненте интелигенције: учење, размишљање, рјешавање проблема, перцепција и разумијевање природног језика. |

|||

Први циљ је студија људских [[спознаја|когнитивних]] процеса уопште, што потврђује дефиницију [[Патрик Хејес|Патрика Ј. Хејеса]] - „студија интелигенције као компутације“, чиме се вештачка интелигенција усмерава ка једној својеврсној студији интелигентног понашања код људи. |

|||

== Учење == |

|||

Вештачка интелигенција, као област информатике, бави се пројектовањем програмских решења за проблеме које настоји решити. |

|||

Постоји више различитих облика учења који су примијењени на област вјештачке интелигенције. Најједноставнији се односи на учење на грешкама преко покушаја. На примјер, најједноставнији рачунарски програм за ријешавање проблема матирања у једном потезу у [[шах]]у, је истраживање мат позиције случајним потезима. Једном изнађено рјешење, програм може запамтити позицију и искористити је сљедећи пут када се нађе у идентичној ситуацији. Једноставно памћење индивидуалних потеза и процедура - познато као [[механичко учење]] - је врло лако имплементирати у рачунарски систем. Приликом покушаја имплементације тзв., уопштавања, јављају се већи проблеми и захтјеви. Уопштавање се састоји од примјене прошлих искустава на аналогне нове ситуације. На примјер, програм који учи прошла времена глагола на српском језику механичким учењем, неће бити способан да изведе прошло вријеме, рецимо глагола скочити, док се не нађе пред обликом глагола скочио, гдје ће програм који је способан за уопштавање научити „додај -о и уклони -ти“ правило, те тако формирати прошло вријеме глагола скочити, заснивајући се на искуству са сличним глаголима. |

|||

== Размишљање == |

=== Размишљање и решавање проблема === |

||

Размишљање је процес извлачења закључака који одговарају датој ситуацији. Закључци се класификују као дедуктивни и индуктивни. |

Размишљање је процес извлачења закључака који одговарају датој ситуацији. Закључци се класификују као дедуктивни и индуктивни. Пример дедуктивног начина закључивања би могао бити, „Саво је или у музеју, или у кафићу. Није у кафићу; онда је сигурно у музеју“; и индуктивног, „Претходне несреће ове врсте су биле последица грешке у систему; стога је и ова несрећа узрокована грешком у систему“. Најзначајнија разлика између ова два начина закључивања је да, у случају дедуктивног размишљања, истинитост премисе гарантује истинитост закључка, док у случају индуктивног размишљања истинитост премисе даје подршку закључку без давања апсолутне сигурности његовој истинитости. Индуктивно закључивање је уобичајено у наукама у којима се сакупљају подаци и развијају провизиони модели за опис и предвиђање будућег понашања, све док се не појаве аномалије у моделу, који се тада реконструише. Дедуктивно размишљање је уобичајено у [[математика|математици]] и [[логика|логици]], где детаљно обрађене структуре непобитних [[теорема]] настају од мањих скупова основних [[аксиома]] и правила. Постоје значајни успеси у програмирању рачунара за извлачење закључака, нарочито дедуктивне природе. Ипак, истинско размишљање се састоји од сложенијих аспеката; укључује закључивање на начин којим ће се решити одређени задатак, или ситуација. Ту се налази један од највећих проблема с којим се сусреће VI. |

||

Решавање проблема, нарочито у вештачкој интелигенцији, карактерише систематска претрага у рангу могућих акција с циљем изналажења неког раније дефинисаног решења. Методе решавања проблема се деле на оне посебне и оне опште намене. Метода посебне намене је тражење адаптираног решења за одређени проблем и садржи врло специфичне особине ситуација од којих се проблем састоји. Супротно томе, метод опште намене се може применити на шири спектар проблема. Техника опште намене која се користи у VI је метод крајње анализе, део по део, или постепено додавање, односно редуковање различитости између тренутног стања и крајњег циља. Програм бира акције из листе метода - у случају једноставног робота кораци су следећи: -{PICKUP}-, -{PUTDOWN}-, -{MOVEFROWARD}-, -{MOVEBACK}-, -{MOVELEFT}- и -{MOVERIGHT}-, све док се циљ не постигне. Већи број различитих проблема су решени преко програма вештачке интелигенције. Неки од примера су тражење победничког потеза, или секвенце потеза у играма, сложени математички докази и манипулација виртуелних објеката у вештачким, односно синтетичким рачунарским световима. |

|||

Постоје значајни успјеси у програмирању рачунара за извлачење закључака, нарочито дедуктивне природе. Ипак, истинско размишљање се састоји од сложенијих аспеката; укључује закључивање на начин којим ће се ријешити одређени задатак, или ситуација. Ту се налази један од највећих проблема с којим се сусреће VI. |

|||

Early researchers developed algorithms that imitated step-by-step reasoning that humans use when they solve puzzles or make logical [[Deductive reasoning|deductions]].<ref> |

|||

== Рјешавање проблема == |

|||

Problem solving, puzzle solving, game playing and deduction: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 3–5}} |

|||

Рјешавање проблема, нарочито у вјештачкој интелигенцији, карактерише систематска претрага у рангу могућих акција с циљем изналажења неког раније дефинисаног рјешења. Методе рјешавања проблема се дијеле на оне посебне и оне опште намјене. Метода посебне намјене је тражење адаптираног рјешења за одређени проблем и садржи врло специфичне особине ситуација од којих се проблем састоји. Супротно томе, метод опште намјене се може примијенити на шири спектар проблема. Техника опште намјене која се користи у VI је метод крајње анализе, дио по дио, или постепено додавање, односно редуковање различитости између тренутног стања и крајњег циља. Програм бира акције из листе метода - у случају једноставног робота кораци су сљедећи: -{PICKUP}-, -{PUTDOWN}-, -{MOVEFROWARD}-, -{MOVEBACK}-, -{MOVELEFT}- и -{MOVERIGHT}-, све док се циљ не постигне. |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 6}} ([[constraint satisfaction]]) |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|loc=chpt. 2, 3, 7, 9}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|loc=chpt. 3, 4, 6, 8}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 7–12}} |

|||

</ref> By the late 1980s and 1990s, methods were developed for dealing with [[uncertainty|uncertain]] or incomplete information, employing concepts from [[probability]] and [[economics]].<ref> |

|||

Uncertain reasoning: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 12–18}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=345–395}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=333–381}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 7–12}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Many of these algorithms are insufficient for solving large reasoning problems because they experience a "combinatorial explosion": they became exponentially slower as the problems grew larger.<ref name="Intractability"> |

|||

Већи број различитих проблема су ријешени преко програма вјештачке интелигенције. Неки од примјера су тражење побједничког потеза, или секвенце потеза у играма, сложени математички докази и манипулација виртуелних објеката у вјештачким, односно синтетичким рачунарским свјетовима. |

|||

[[Intractably|Intractability and efficiency]] and the [[combinatorial explosion]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|p=21}} |

|||

== Историјски преглед развоја == |

|||

</ref> Even humans rarely use the step-by-step deduction that early AI research could model. They solve most of their problems using fast, intuitive judgments.<ref name="Psychological evidence of sub-symbolic reasoning"> |

|||

Psychological evidence of the prevalence sub-symbolic reasoning and knowledge: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Kahneman|2011}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Dreyfus|Dreyfus|1986}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Wason|Shapiro|1966}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Kahneman|Slovic|Tversky|1982}} |

|||

</ref> Accurate and efficient reasoning is an unsolved problem. |

|||

=== Knowledge representation === |

|||

Појам '''вјештачка интелигенција (VI)''', настаје љета [[1956]]. године у [[Дартмуд]]у, [[Хановер (САД)]], на скупу истраживача заинтересованих за теме [[интелигенција|интелигенције]], [[неуронска мрежа (вештачка интелигенција)|неуронских мрежа]] и [[теорија аутомата|теорије аутомата]]. Скуп је организовао [[Џон Макарти (информатичар)|Џон Макарти]], уједно са [[Klod Elvud Šenon|Клодом Шеноном]], [[Марвин Мински|Марвином Минским]] и Н. Рочестером. На скупу су такође учествовали Т. Мур ([[Универзитет Принстон|Принстон]]), А. Семјуел ([[IBM]]), Р. Соломоноф и О. Селфриџ ([[Масачусетски институт технологије|МИТ]]), као и А. Невил, Х. Сајмон (-{Carnegie Tech}-, данас -{Carnegie Mellon University}-). На скупу су постављене основе области вјештачке интелигенције и трасиран пут за њен даљи развој. |

|||

[[File:General Formal Ontology.svg|thumb|upright=1.2|An ontology represents knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain and the relationships between those concepts.]] |

|||

[[Knowledge representation]] and [[knowledge engineering]]<ref> |

|||

Раније, [[1950]]. године, [[Алан Тјуринг]] је објавио један чланак у ревији Мајнд ''(-{Mind}-)'', под насловом „Рачунари и интелигенција“, гдје говори о концепту вјештачке интелигенције и поставља основе једне врсте пробе, преко које би се утврђивало да ли се одређени рачунарски систем понаша у складу са оним што се подразумијева под вјештачком интелигенцијом, или не. Касније ће та врста пробе добити име, [[Тјурингов тест]]. |

|||

[[Knowledge representation]] and [[knowledge engineering]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 10}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=23–46, 69–81, 169–233, 235–277, 281–298, 319–345}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=227–243}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 17.1–17.4, 18}} |

|||

</ref> allow AI programs to answer questions intelligently and make deductions about real-world facts. Formal knowledge representations are used in content-based indexing and retrieval,{{sfnp|Smoliar|Zhang|1994}} scene interpretation,{{sfnp|Neumann|Möller|2008}} clinical decision support,{{sfnp|Kuperman|Reichley|Bailey|2006}} knowledge discovery (mining "interesting" and actionable inferences from large [[Database|databases]]),{{sfnp|McGarry|2005}} and other areas.{{sfnp|Bertini|Del Bimbo|Torniai|2006}} |

|||

A [[knowledge base]] is a body of knowledge represented in a form that can be used by a program. An [[ontology (information science)|ontology]] is the set of objects, relations, concepts, and properties used by a particular domain of knowledge.{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=272}} Knowledge bases need to represent things such as: objects, properties, categories and relations between objects;<ref name="Representing categories and relations"> |

|||

Скуп је посљедица првих радова у области. Невил и Сајмон су на њему представили свој програм за [[аутоматско резоновање]], Логиц Тхеорист (који је направио сензацију). Данас се сматра да су концепт вјештачке интелигенције поставили В. Мекулок и M. Питс, [[1943]]. године, у раду у ком се представља модел вјештачких неурона на бази три извора: [[спознаја]] о физиологији и функционисању можданих неурона, [[исказна логика]] [[Бертранд Расел|Расела]] и Вајтехеда, и Тјурингова [[компутациона теорија]]. Неколико година касније створен је први неурални рачунар -{SNARC}-. Заслужни за подухват су студенти Принстона, Марвин Мински и Д. Едмонс, [[1951]]. године. Негдје из исте епохе су и први програми за [[шах]], чији су аутори Шенон и Тјуринг. |

|||

Representing categories and relations: [[Semantic network]]s, [[description logic]]s, [[Inheritance (object-oriented programming)|inheritance]] (including [[Frame (artificial intelligence)|frames]] and [[Scripts (artificial intelligence)|scripts]]): |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§10.2 & 10.5}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=174–177}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=248–258}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 18.3}} |

|||

</ref> situations, events, states and time;<ref name="Representing time">Representing events and time:[[Situation calculus]], [[event calculus]], [[fluent calculus]] (including solving the [[frame problem]]): |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§10.3}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=281–298}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 18.2}} |

|||

</ref> causes and effects;<ref name="Representing causation"> |

|||

[[Causality#Causal calculus|Causal calculus]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=335–337}} |

|||

</ref> knowledge about knowledge (what we know about what other people know);<ref name="Representing knowledge about knowledge"> |

|||

Representing knowledge about knowledge: Belief calculus, [[modal logic]]s: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§10.4}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=275–277}} |

|||

</ref> [[default reasoning]] (things that humans assume are true until they are told differently and will remain true even when other facts are changing);<ref name="Default reasoning and non-monotonic logic"> |

|||

[[Default reasoning]], [[Frame problem]], [[default logic]], [[non-monotonic logic]]s, [[circumscription (logic)|circumscription]], [[closed world assumption]], [[abductive reasoning|abduction]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§10.6}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=248–256, 323–335}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=335–363}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=~18.3.3}} |

|||

(Poole ''et al.'' places abduction under "default reasoning". Luger ''et al.'' places this under "uncertain reasoning"). |

|||

</ref> and many other aspects and domains of knowledge. |

|||

Among the most difficult problems in knowledge representation are: the breadth of commonsense knowledge (the set of atomic facts that the average person knows is enormous);<ref name="Breadth of commonsense knowledge"> |

|||

Иако се ова истраживања сматрају зачетком вјештачке интелигенције, постоје многа друга који су битно утјецала на развој ове области. Нека потичу из области као што су [[филозофија]] (први покушаји формализације резоновања су [[силогизам|силогизми]] грчког филозофа [[Аристотел]]а), [[математика]] (теорија одлучивања и [[теорија пробабилитета]] се примјењују у многим данашњим системима), или [[психологија]] (која је заједно са вјештачком интелигенцијом формирала област [[когнитивна наука|когнитивне науке]]). |

|||

Breadth of commonsense knowledge: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Lenat|Guha|1989|loc=Introduction}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Crevier|1993|pp=113–114}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Moravec|1988|p=13}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=241, 385, 982}} ([[qualification problem]]) |

|||

</ref> and the sub-symbolic form of most commonsense knowledge (much of what people know is not represented as "facts" or "statements" that they could express verbally).<ref name="Psychological evidence of sub-symbolic reasoning"/> There is also the difficulty of [[knowledge acquisition]], the problem of obtaining knowledge for AI applications.{{efn|It is among the reasons that [[expert system]]s proved to be inefficient for capturing knowledge.{{sfnp|Newquist|1994|p=296}}{{sfnp|Crevier|1993|pp=204–208}}}} |

|||

=== Planning and decision making === |

|||

У годинама које слиједе скуп у Дартмуду постижу се значајни напреци. Конструишу се програми који рјешавају различите проблеме. На примјер, студенти Марвина Минског ће крајем шездесетих година имплементирати програм -{Analogy}-, који је оспособљен за рјешавање геометријских проблема, сличним онима који се јављају у [[тест интелигенције|тестовима интелигенције]], и програм Стјудент, који рјешава [[алгебра|алгебарске]] проблеме написане на [[енглески језик|енглеском језику]]. Невил и Сајмон ће развити ''-{General Problem Solver}- (-{ГПС}-)'', који покушава имитирати људско резоновање. Семјуел је написао програме за игру сличну дами, који су били оспособљени за учење те игре. Макарти, који је у међувремену отишао на МИТ, имплементира програмски језик [[Lisp (programski jezik)|Lisp]], [[1958]]. године. Исте године је написао чланак, ''-{Programs With Common Sense}-'', гдје описује један хипотетички програм који се сматра првим комплетним системом вјештачке интелигенције. |

|||

An "agent" is anything that perceives and takes actions in the world. A [[rational agent]] has goals or preferences and takes actions to make them happen.{{efn| |

|||

Ова серија успјеха се ломи средином шездесетих година и превише оптимистичка предвиђања из ранијих година се фрустрирају. До тада имплементирани системи су функционисали у ограниченим доменима, познатим као микросвијетови (-{microworlds}-). Трансформација која би омогућила њихову примјену у стварним окружењима није била тако лако изводљива, упркос очекивањима многих истраживача. По Раселу и Норивигу, постоје три фундаментална фактора који су то онемогућили: |

|||

"Rational agent" is general term used in [[economics]], [[philosophy]] and theoretical artificial intelligence. It can refer to anything that directs its behavior to accomplish goals, such as a person, an animal, a corporation, a nation, or, in the case of AI, a computer program. |

|||

# Многи дизајнирани системи нису посједовали сазнање о окружењу примјене, или је имплементирано сазнање било врло ниског нивоа и састојало се од неких једноставних синтактичких манипулација. |

|||

}}{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|p=528}} In [[automated planning and scheduling|automated planning]], the agent has a specific goal.<ref> |

|||

# Многи проблеми које су покушавали ријешити су били у суштини нерјешиви, боље речено, док је количина сазнања била мала и ограничена рјешење је било могуће, али када би дошло до пораста обима сазнања, проблеми постају нерјешиви. |

|||

[[Automated planning and scheduling|Automated planning]]: |

|||

# Неке од основних структура које су се користиле за стварање одређеног интелигентног понашања су биле веома ограничене. |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 11}}. |

|||

</ref> In [[automated decision making]], the agent has preferences – there are some situations it would prefer to be in, and some situations it is trying to avoid. The decision making agent assigns a number to each situation (called the "[[utility (economics)|utility]]") that measures how much the agent prefers it. For each possible action, it can calculate the "[[expected utility]]": the [[utility]] of all possible outcomes of the action, weighted by the probability that the outcome will occur. It can then choose the action with the maximum expected utility.<ref> |

|||

[[Automated decision making]], [[Decision theory]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 16–18}}. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

In [[Automated planning and scheduling#classical planning|classical planning]], the agent knows exactly what the effect of any action will be.<ref> |

|||

[[Automated planning and scheduling#classical planning|Classical planning]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Section 11.2}}. |

|||

</ref> In most real-world problems, however, the agent may not be certain about the situation they are in (it is "unknown" or "unobservable") and it may not know for certain what will happen after each possible action (it is not "deterministic"). It must choose an action by making a probabilistic guess and then reassess the situation to see if the action worked.<ref> |

|||

Sensorless or "conformant" planning, contingent planning, replanning (a.k.a online planning): |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Section 11.5}}. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

In some problems, the agent's preferences may be uncertain, especially if there are other agents or humans involved. These can be learned (e.g., with [[inverse reinforcement learning]]) or the agent can seek information to improve its preferences.<ref> |

|||

Uncertain preferences: |

|||

*{{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Section 16.7}} |

|||

[[Inverse reinforcement learning]]: |

|||

*{{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Section 22.6}} |

|||

</ref> [[Information value theory]] can be used to weigh the value of exploratory or experimental actions.<ref> |

|||

[[Information value theory]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Section 16.6}}. |

|||

</ref> The space of possible future actions and situations is typically [[intractable problem|intractably]] large, so the agents must take actions and evaluate situations while being uncertain what the outcome will be. |

|||

A [[Markov decision process]] has a [[Finite-state machine|transition model]] that describes the probability that a particular action will change the state in a particular way, and a [[reward function]] that supplies the utility of each state and the cost of each action. A [[Reinforcement learning#Policy|policy]] associates a decision with each possible state. The policy could be calculated (e.g., by [[policy iteration|iteration]]), be [[heuristic]], or it can be learned.<ref> |

|||

[[Markov decision process]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 17}}. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

[[Game theory]] describes rational behavior of multiple interacting agents, and is used in AI programs that make decisions that involve other agents.<ref> |

|||

[[Game theory]] and multi-agent decision theory: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 18}}. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

=== Учење === |

|||

Постоји више различитих облика учења који су примењени на област вештачке интелигенције. Најједноставнији се односи на учење на грешкама преко покушаја. На пример, најједноставнији рачунарски програм за решавање проблема матирања у једном потезу у [[шах]]у, је истраживање мат позиције случајним потезима. Једном изнађено решење, програм може запамтити позицију и искористити је следећи пут када се нађе у идентичној ситуацији. Једноставно памћење индивидуалних потеза и процедура - познато као [[механичко учење]] - је врло лако имплементирати у рачунарски систем. Приликом покушаја имплементације тзв. уопштавања, јављају се већи проблеми и захтеви. Уопштавање се састоји од примене прошлих искустава на аналогне нове ситуације. На пример, програм који учи прошла времена глагола на српском језику механичким учењем, неће бити способан да изведе прошло време, рецимо глагола скочити, док се не нађе пред обликом глагола скочио, где ће програм који је способан за уопштавање научити „додај -о и уклони -ти“ правило, те тако формирати прошло време глагола скочити, заснивајући се на искуству са сличним глаголима. |

|||

[[Machine learning]] is the study of programs that can improve their performance on a given task automatically.<ref name ="machine learning"> |

|||

[[machine learning|Learning]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 19–22}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=397–438}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=385–542}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 3.3, 10.3, 17.5, 20}} |

|||

</ref> It has been a part of AI from the beginning.{{efn |

|||

|[[Alan Turing]] discussed the centrality of learning as early as 1950, in his classic paper "[[Computing Machinery and Intelligence]]".{{sfnp|Turing|1950}} In 1956, at the original Dartmouth AI summer conference, [[Ray Solomonoff]] wrote a report on unsupervised probabilistic machine learning: "An Inductive Inference Machine".{{sfnp|Solomonoff|1956}} |

|||

}} |

|||

There are several kinds of machine learning. [[Unsupervised learning]] analyzes a stream of data and finds patterns and makes predictions without any other guidance.<ref> |

|||

[[Unsupervised learning]]: |

|||

* {{harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=653}} (definition) |

|||

* {{harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=738–740}} ([[cluster analysis]]) |

|||

* {{harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=846–860}} ([[word embedding]]) |

|||

</ref> [[Supervised learning]] requires a human to label the input data first, and comes in two main varieties: [[statistical classification|classification]] (where the program must learn to predict what category the input belongs in) and [[Regression analysis|regression]] (where the program must deduce a numeric function based on numeric input).<ref name="Supervised learning"> |

|||

[[Supervised learning]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§19.2}} (Definition) |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Chpt. 19–20}} (Techniques) |

|||

</ref> |

|||

In [[reinforcement learning]] the agent is rewarded for good responses and punished for bad ones. The agent learns to choose responses that are classified as "good".<ref> |

|||

[[Reinforcement learning]]: |

|||

*{{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 22}} |

|||

*{{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=442–449}} |

|||

</ref> [[Transfer learning]] is when the knowledge gained from one problem is applied to a new problem.<ref> |

|||

[[Transfer learning]]: |

|||

*{{harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=281}} |

|||

*{{harvtxt|The Economist|2016}} |

|||

</ref> [[Deep learning]] is a type of machine learning that runs inputs through biologically inspired [[artificial neural networks]] for all of these types of learning.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Artificial Intelligence (AI): What Is AI and How Does It Work? {{!}} Built In |url=https://builtin.com/artificial-intelligence |access-date=2023-10-30 |website=builtin.com}}</ref> |

|||

[[Computational learning theory]] can assess learners by [[computational complexity]], by [[sample complexity]] (how much data is required), or by other notions of [[optimization theory|optimization]].<ref> |

|||

[[Computational learning theory]]: |

|||

* {{harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=672–674}} |

|||

* {{harvtxt|Jordan|Mitchell|2015}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

=== Natural language processing === |

|||

[[Natural language processing]] (NLP)<ref> |

|||

[[Natural language processing]] (NLP): |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 23–24}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=91–104}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=591–632}} |

|||

</ref> allows programs to read, write and communicate in human languages such as [[English (language)|English]]. Specific problems include [[speech recognition]], [[speech synthesis]], [[machine translation]], [[information extraction]], [[information retrieval]] and [[question answering]].<ref> |

|||

Subproblems of [[Natural language processing|NLP]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=849–850}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Early work, based on [[Noam Chomsky]]'s [[generative grammar]] and [[semantic network]]s, had difficulty with [[word-sense disambiguation]]{{efn|See {{section link|AI winter|Machine translation and the ALPAC report of 1966 |

|||

}}}} unless restricted to small domains called "[[blocks world|micro-worlds]]" (due to the common sense knowledge problem<ref name="Breadth of commonsense knowledge" />). [[Margaret Masterman]] believed that it was meaning, and not grammar that was the key to understanding languages, and that [[thesauri]] and not dictionaries should be the basis of computational language structure. |

|||

Modern deep learning techniques for NLP include [[word embedding]] (representing words, typically as [[Vector space|vectors]] encoding their meaning),{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|p=856–858}} [[transformer (machine learning model)|transformer]]s (a deep learning architecture using an [[Attention (machine learning)|attention]] mechanism),{{sfnp|Dickson|2022}} and others.<ref>Modern statistical and deep learning approaches to [[Natural language processing|NLP]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 24}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Cambria|White|2014}} |

|||

</ref> In 2019, [[generative pre-trained transformer]] (or "GPT") language models began to generate coherent text,{{sfnp|Vincent|2019}}{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|p=875–878}} and by 2023 these models were able to get human-level scores on the [[bar exam]], [[scholastic aptitude test|SAT]] test, [[Graduate Record Examinations|GRE]] test, and many other real-world applications.{{sfnp|Bushwick|2023}} |

|||

=== Perception === |

|||

[[Machine perception]] is the ability to use input from sensors (such as cameras, microphones, wireless signals, active [[lidar]], sonar, radar, and [[tactile sensor]]s) to deduce aspects of the world. [[Computer vision]] is the ability to analyze visual input.<ref> |

|||

[[Computer vision]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 25}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 6}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The field includes [[speech recognition]],{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=849–850}} [[image classification]],{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=895–899}} [[facial recognition system|facial recognition]], [[object recognition]],{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=899–901}} and [[robotic sensing|robotic perception]].{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=931–938}} |

|||

До тог момента рјешавање проблема је било засновано на једном механизму опште претраге преко којег се покушавају повезати, корак по корак, елементарне основе размишљања да би се дошло до коначног рјешења. Наравно такав приступ подразумијева и велике издатке, те да би се смањили, развијају се први алгоритми за потребе контролисања трошкова истраживања. На примјер, [[Едсгер Дајкстра|Едсхер Дајкстра]] [[1959]]. године дизајнира један метод за стабилизацију издатака, Невил и Ернст, [[1965]]. године развијају концепт [[хеуристика|хеуристичке]] претраге и Харт, Нилсон и Рафаел, алгоритам А. У исто вријеме, у вези програма за игре, дефинише се претрага алфа-бета. Творац идеје је иначе био Макарти, [[1956]]. године, а касније ју је користио Невил, [[1958]]. године. |

|||

=== Social intelligence === |

|||

Важност схватања сазнања у контексту домена и примјене, као и грађе структуре, којој би било лако приступати, довела је до детаљнијих студија метода представљања сазнања. Између осталих, дефинисале су се семантичке мреже (дефинисане почетком шездесетих година, од стране Килијана) и окружења (које је дефинисао Мински [[1975]]. године). У истом периоду почињу да се користе одређене врсте логике за представљање сазнања. |

|||

[[File:Kismet-IMG 6007-gradient.jpg|thumb|[[Kismet (robot)|Kismet]], a robot head which was made in the 1990s; a machine that can recognize and simulate emotions.{{sfnp|MIT AIL|2014}}]] |

|||

[[Affective computing]] is an interdisciplinary umbrella that comprises systems that recognize, interpret, process or simulate human [[Affect (psychology)|feeling, emotion and mood]].<ref> |

|||

Паралелно с тим, током истих година, настављају се истраживања за стварање система за игру чекерс, за који је заслужан Самуел, оријентисан на имплементацију неке врсте методе учења. Е. Б. Хунт, Ј. Мартин и П. Т. Стоне, [[1969]]. године конструишу хијерархијску структуру одлука (ради класификације), коју је већ идејно поставио Шенон, [[1949]]. године. Килијан, [[1979]], представља метод -{IDZ}- који треба да послужи као основа за конструкцију такве структуре. С друге стране, П. Винстон, 1979. године, развија властити програм за учење описа сложених објеката, и Т. Мичел, [[1977]], развија тзв., простор верзија. Касније, средином осамдесетих, поновна примјена методе учења на неуралне мреже тзв., -{backpropagation}-, доводи до поновног оживљавања ове области. |

|||

[[Affective computing]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Thro|1993}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Edelson|1991}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Tao|Tan|2005}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Scassellati|2002}} |

|||

</ref> For example, some [[virtual assistant]]s are programmed to speak conversationally or even to banter humorously; it makes them appear more sensitive to the emotional dynamics of human interaction, or to otherwise facilitate [[human–computer interaction]]. |

|||

However, this tends to give naïve users an unrealistic conception of the intelligence of existing computer agents.{{sfnp|Waddell|2018}} Moderate successes related to affective computing include textual [[sentiment analysis]] and, more recently, [[multimodal sentiment analysis]], wherein AI classifies the affects displayed by a videotaped subject.{{sfnp|Poria|Cambria|Bajpai |Hussain|2017}} |

|||

Конструкција апликација за стварна окружења, довела је до потребе разматрања аспеката као што су неизвјесност, или непрецизност (који се такође јављају приликом рјешавања проблема у играма). За рјешавање ових проблема примјењиване су пробабилистичке методе (теорија пробабилитета, или пробабилистичке мреже) и развијали други формализми као дифузни скупови (дефинисани од Л. Задеха [[1965]]. године), или [[Демпстер-Шаферова теорија]] (творац теорије је А. Демпстер, [[1968]], са значајним доприносом Г. Шафера [[1976]]. године). |

|||

=== General intelligence === |

|||

На основу ових истраживања, почев од осамдесетих година, конструишу се први комерцијални системи вјештачке интелигенције, углавном тзв., експертски системи. |

|||

A machine with [[artificial general intelligence]] should be able to solve a wide variety of problems with breadth and versatility similar to human intelligence.<ref name = "AGI" > |

|||

Савремени проблеми који се настоје ријешити у истраживањима вјештачке интелигенције, везани су за настојања конструисања кооперативних система на бази [[агент (рачунарство)|агената]], укључујући системе за управљање подацима, утврђивање редослиједа обраде података и покушаје имитације природног језика, између осталих. |

|||

[[Artificial general intelligence]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=32–33, 1020–1021}} |

|||

Proposal for the modern version: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Pennachin|Goertzel|2007}} |

|||

Warnings of overspecialization in AI from leading researchers: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1995}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|McCarthy|2007}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Beal|Winston|2009}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

== Проблем дефиниције |

== Проблем дефиниције вештачке интелигенције == |

||

За разлику од других области, у |

За разлику од других области, у вештачкој интелигенцији не постоји сагласност око једне дефиниције, него их има више зависно од различитих погледа и метода за решавање проблема. |

||

=== Дефиниција и циљеви === |

=== Дефиниција и циљеви === |

||

Упркос времену које је прошло од када је [[Џон Макарти (информатичар)|Џон Макарти]] дао име овој области на конференцији одржаној [[1956]]. године у Дартмуду, није нимало лако тачно дефинисати садржај и достигнућа |

Упркос времену које је прошло од када је [[Џон Макарти (информатичар)|Џон Макарти]] дао име овој области на конференцији одржаној [[1956]]. године у Дартмуду, није нимало лако тачно дефинисати садржај и достигнућа вештачке интелигенције. |

||

Највероватније, једна од најкраћих и најједноставнијих карактеристика која се приписује вештачкој интелигенцији, парафразирајући [[Марвин Мински|Марвина Минског]], (једног од стручњака и најпознатијих истраживача вештачке интелигенције), је „конструисање рачунарских система са особинама које би код људских бића биле окарактерисане као интелигентне“. |

|||

=== Тјурингов тест === |

=== Тјурингов тест === |

||

[[Датотека:Тјурингов тест.png|мини|десно|Људско и ''вештачко интелигентно'' понашање.]] |

[[Датотека:Тјурингов тест.png|мини|десно|Људско и ''вештачко интелигентно'' понашање.]] |

||

У познатом такозваном [[Тјурингов тест|Тјуринговом тесту]], који је [[Алан Тјуринг]] описао и објавио у једном чланку из [[1950]]. године, под насловом ''-{Computing machinery and intelligence}-'' (''Рачунске машине и интелигенција''), предлаже се један експеримент чији је циљ откривање интелигентног понашања једне машине. |

|||

Тест полази од једне игре у којој испитивач треба да погоди [[пол]] два интерлокутора, A и Б, а који се налазе у посебним и одвојеним собама. Иако обоје тврде да су женског пола, у ствари ради се о мушкарцу и жени. У изворном Тјуринговом |

У познатом такозваном [[Тјурингов тест|Тјуринговом тесту]], који је [[Алан Тјуринг]] описао и објавио у једном чланку из [[1950]]. године, под насловом ''-{Computing machinery and intelligence}-'' (''Рачунске машине и интелигенција''), предлаже се један експеримент чији је циљ откривање интелигентног понашања једне машине. Тест полази од једне игре у којој испитивач треба да погоди [[пол]] два интерлокутора, A и Б, а који се налазе у посебним и одвојеним собама. Иако обоје тврде да су женског пола, у ствари ради се о мушкарцу и жени. У изворном Тјуринговом предлогу урађена је извесна модификација, те је жену заменио рачунар. Испитивач треба да погоди ко је од њих машина, полазећи од њиховог међусобног разговора и имајући у виду да обоје тврде да су људи. Задатак треба постићи упркос чињеници да ниједан од интерлокутора није обавезан да говори истину, те на пример, машина може одлучити да да погрешан резултат једне аритметичке операције, или чак да га саопшти много касније како би варка била уверљивија. |

||

По оптимистичкој хипотези самог Тјуринга, око [[2000]]. године, већ је требало да постоје рачунари оспособљени за игру ове игре довољно добро, тако да просечан испитивач нема више од 70% шансе да уради исправну идентификацију, након пет минута постављања питања. Када би то данас заиста било тако, налазили би се пред једном истински интелигентном машином, или у најмању руку машином која уме да се представи као интелигентна. Не треба ни поменути да су Тјурингова предвиђања била превише оптимистична, што је био врло чест случај у самим почецима развоја области вештачке интелигенције. У стварности проблем није само везан за способност рачунара за обраду података, него на првом мјесту, за могућност програмирања рачунара са способностима за интелигентно понашање. |

|||

Задатак треба постићи упркос чињеници да ниједан од интерлокутора није обавезан да говори истину, те на примјер, машина може одлучити да да погрешан резултат једне аритметичке операције, или чак да га саопшти много касније како би варка била увјерљивија. |

|||

== Вештачка интелигенција у образовању == |

|||

По оптимистичкој хипотези самог Тјуринга, око [[2000]]. године, већ је требало да постоје рачунари оспособљени за игру ове игре довољно добро, тако да просјечан испитивач нема више од 70% шансе да уради исправну идентификацију, након пет минута постављања питања. |

|||

Сан о рачунарима који би могли да образују ученике и студенте, више деценија је инспирисао научнике [[когнитивна наука|когнитивне науке]]. Прва генерација таквих система (названи ''-{Computer Aided Instruction}-'' или ''-{Computer Based Instruction}-''), углавном су се заснивали на [[хипертекст]]у. Структура тих система се састојала од презентације материјала и питања са више избора, која шаљу ученика на даље информације, у зависности од одговора на постављена питања. |

|||

Када би то данас заиста било тако, налазили би се пред једном истински интелигентном машином, или у најмању руку машином која умије да се представи као интелигентна. |

|||

Наредна генерација ових система ''-{Intelligent CAI}-'' или ''-{Intelligent Tutoring Systems}-'', заснивали су се на имплементацији знања о одређеној теми, у сам рачунар. Постајала су два типа оваквих система. Први је тренирао ученика у самом процесу решавања сложених проблема, као што је нпр. препознавање грешака дизајна у једном [[електрична кола|електричном колу]] или писање рачунарског програма. Други тип система је покушавао да одржава [[силогизам|силогистички дијалог]] са студентима. Имплементацију другог типа система је било врло тешко спровести у праксу, великим делом због проблема програмирања система за разумевање спонтаног и природног људског језика. Из тог разлога, пројектовано их је само неколико. |

|||

Не треба ни поменути да су Тјурингова предвиђања била превише оптимистична, што је био врло чест случај у самим почецима развоја области вјештачке интелигенције. |

|||

Типични систем за тренирање ученика и студената се обично састоји од четири основне компоненте. |

|||

У стварности проблем није само везан за способност рачунара за обраду података, него на првом мјесту, за могућност програмирања рачунара са способностима за интелигентно понашање. |

|||

# Прва компонента је окружење у којем ученик или студент ради на решавању сложених задатака. То може бити симулација компоненте или компонената електронских уређаја представљена као серија проблема које студент треба да реши. |

|||

# Друга компонента је [[ekspertski sistemi|експертски систем]] који може решити представљене проблеме на којима студент ради. |

|||

# Трећу чини један посебан модул који може упоредити решења која нуди студент са онима које су уграђене у експертски систем и његов циљ је да препозна студентов план за решење проблема, као и које делове знања највероватније студент користи. |

|||

# Четврту чини [[педагогија|педагошки]] модул који сугерише задатке које треба решити, одговара на питања студента и указује му на могуће грешке. Одговори на питања студента и сугестије за планирање решавања задатака, заснивају се на прикупљеним подацима из претходног модула. |

|||

Свака од ових компонената може користити технологију вештачке интелигенције. Окружење може садржати софистицирану симулацију или [[интелигентни агент|интелигентног агента]], односно симулираног студента или чак опонента студенту. Модул који чини експертски систем се састоји од класичних проблема вештачке интелигенције, као што су препознавање плана и резоновање над проблемима који укључују неизвесност. Задатак педагошког модула је надгледање плана инструкције и његово адаптирање на основу нових информација о компетентности студента за решавање проблема. Упркос сложености система за тренирање ученика и студената, пројектовани су у великом броју, а неки од њих се регуларно користе у школама, [[индустрија|индустрији]] и за [[војска|војне инструкције]]. |

|||

== Основни циљеви истраживања на пољу вјештачке интелигенције == |

|||

== Технике == |

|||

Тренутно, када су у питању истраживања на пољу вјештачке интелигенције, могуће је постићи два комплементарна циља, који респективно наглашавају два аспекта вјештачке интелигенције, а то су теоријски и технолошки аспект. |

|||

AI research uses a wide variety of techniques to accomplish the goals above.{{efn|name="Tools of AI"|This list of tools is based on the topics covered by the major AI textbooks, including: {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021}}, {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004}}, {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998}} and {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998}}}} |

|||

Први циљ је студија људских [[спознаја|когнитивних]] процеса уопште, што потврђује дефиницију [[Патрик Хејес|Патрика Ј. Хејеса]] - „студија интелигенције као компутације“, чиме се вјештачка интелигенција усмјерава ка једној својеврсној студији интелигентног понашања код људи. |

|||

=== Search and optimization === |

|||

=== Конструкција програмских рјешења === |

|||

AI can solve many problems by intelligently searching through many possible solutions.<ref> |

|||

[[Search algorithm]]s: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Chpt. 3–5}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=113–163}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=79–164, 193–219}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 7–12}} |

|||

</ref> There are two very different kinds of search used in AI: [[state space search]] and [[Local search (optimization)|local search]]. |

|||

==== State space search ==== |

|||

Вјештачка интелигенција, као област информатике, бави се пројектовањем програмских рјешења за проблеме које настоји ријешити. |

|||

[[State space search]] searches through a tree of possible states to try to find a goal state.<ref name="State space search"> |

|||

[[State space search]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 3}} |

|||

</ref> For example, [[Automated planning and scheduling|planning]] algorithms search through trees of goals and subgoals, attempting to find a path to a target goal, a process called [[means-ends analysis]].{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§11.2}} |

|||

[[Brute force search|Simple exhaustive searches]]<ref name="Uninformed search">[[Uninformed search]]es ([[breadth first search]], [[depth-first search]] and general [[state space search]]): |

|||

== Вјештачка интелигенција у образовању == |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§3.4}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=113–132}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=79–121}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 8}} |

|||

</ref> are rarely sufficient for most real-world problems: the [[Search algorithm|search space]] (the number of places to search) quickly grows to [[Astronomically large|astronomical numbers]]. The result is a search that is [[Computation time|too slow]] or never completes.<ref name="Intractability"/> "[[Heuristics]]" or "rules of thumb" can help to prioritize choices that are more likely to reach a goal.<ref name="Informed search"> |

|||

[[Heuristic]] or informed searches (e.g., greedy [[Best-first search|best first]] and [[A* search algorithm|A*]]): |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=s§3.5}} |

|||

Сан о рачунарима који би могли да образују ученике и студенте, више деценија је инспирисао научнике [[когнитивна наука|когнитивне науке]]. Прва генерација таквих система (названи ''-{Computer Aided Instruction}-'' или ''-{Computer Based Instruction}-''), углавном су се заснивали на [[хипертекст]]у. Структура тих система се састојала од презентације материјала и питања са више избора, која шаљу ученика на даље информације, у зависности од одговора на постављена питања. |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=132–147}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|2017|loc=§3.6}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=133–150}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

[[Adversarial search]] is used for [[game AI|game-playing]] programs, such as chess or Go. It searches through a [[Game tree|tree]] of possible moves and counter-moves, looking for a winning position.<ref> |

|||

Наредна генерација ових система ''-{Intelligent CAI}-'' или ''-{Intelligent Tutoring Systems}-'', заснивали су се на имплементацији знања о одређеној теми, у сам рачунар. Постајала су два типа оваквих система. Први је тренирао ученика у самом процесу рјешавања сложених проблема, као што је нпр., препознавање грешака дизајна у једном [[електрична кола|електричном колу]] или писање рачунарског програма. Други тип система је покушавао да одржава [[силогизам|силогистички дијалог]] са студентима. Имплементацију другог типа система је било врло тешко спровести у праксу, великим дијелом због проблема програмирања система за разумијевање спонтаног и природног људског језика. Из тог разлога, пројектовано их је само неколико. |

|||

[[Adversarial search]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 5}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

==== Local search ==== |

|||

Типични систем за тренирање ученика и студената се обично састоји од четири основне компоненте. |

|||

[[File:Gradient descent.gif|thumb|Illustration of [[gradient descent]] for 3 different starting points. Two parameters (represented by the plan coordinates) are adjusted in order to minimize the [[loss function]] (the height).]][[Local search (optimization)|Local search]] uses [[mathematical optimization]] to find a solution to a problem. It begins with some form of guess and refines it incrementally.<ref name="Local search2">[[Local search (optimization)|Local]] or "[[Mathematical optimization|optimization]]" search: |

|||

# Прва компонента је окружење у којем ученик или студент ради на рјешавању сложених задатака. То може бити симулација компоненте или компонената електронских уређаја представљена као серија проблема које студент треба да ријеши. |

|||

# Друга компонента је [[ekspertski sistemi|експертски систем]] који може ријешити представљене проблеме на којима студент ради. |

|||

# Трећу чини један посебан модул који може упоредити рјешења која нуди студент са онима које су уграђене у експертски систем и његов циљ је да препозна студентов план за рјешење проблема, као и које дијелове знања највјероватније студент користи. |

|||

# Четврту чини [[педагогија|педагошки]] модул који сугерише задатке које треба ријешити, одговара на питања студента и указује му на могуће грешке. Одговори на питања студента и сугестије за планирање рјешавања задатака, заснивају се на прикупљеним подацима из претходног модула. |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 4}}</ref> |

|||

Свака од ових компонената може користити технологију вјештачке интелигенције. Окружење може садржати софистицирану симулацију или [[интелигентни агент|интелигентног агента]], односно симулираног студента или чак опонента студенту. Модул који чини експертски систем се састоји од класичних проблема вјештачке интелигенције, као што су препознавање плана и резоновање над проблемима који укључују неизвјесност. Задатак педагошког модула је надгледање плана инструкције и његово адаптирање на основу нових информација о компетентности студента за рјешавање проблема. Упркос сложености система за тренирање ученика и студената, пројектовани су у великом броју, а неки од њих се регуларно користе у школама, [[индустрија|индустрији]] и за [[војска|војне инструкције]]. |

|||

[[Gradient descent]] is a type of local search that optimizes a set of numerical parameters by incrementally adjusting them to minimize a [[loss function]]. Variants of gradient descent are commonly used to train neural networks.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Singh Chauhan |first=Nagesh |date=December 18, 2020 |title=Optimization Algorithms in Neural Networks |url=https://www.kdnuggets.com/optimization-algorithms-in-neural-networks |access-date=2024-01-13 |website=KDnuggets |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

Another type of local search is [[evolutionary computation]], which aims to iteratively improve a set of candidate solutions by "mutating" and "recombining" them, [[Artificial selection|selecting]] only the fittest to survive each generation.<ref> |

|||

[[Evolutionary computation]]: |

|||

*{{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§4.1.2}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Distributed search processes can coordinate via [[swarm intelligence]] algorithms. Two popular swarm algorithms used in search are [[particle swarm optimization]] (inspired by bird [[Flocking (behavior)|flocking]]) and [[ant colony optimization]] (inspired by [[ant trail]]s).{{sfnp|Merkle|Middendorf|2013}} |

|||

=== Logic === |

|||

Formal [[Logic]] is used for [[automatic reasoning|reasoning]] and [[knowledge representation]].<ref name="Logic"> |

|||

[[Logic]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 6–9}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=35–77}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 13–16}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Formal logic comes in two main forms: [[propositional logic]] (which operates on statements that are true or false and uses [[logical connective]]s such as "and", "or", "not" and "implies")<ref name="Propositional logic"> |

|||

[[Propositional logic]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 6}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=45–50}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 13}}</ref> |

|||

and [[predicate logic]] (which also operates on objects, predicates and relations and uses [[Quantifier (logic)|quantifier]]s such as "''Every'' ''X'' is a ''Y''" and "There are ''some'' ''X''s that are ''Y''s").<ref name="Predicate logic"> |

|||

[[First-order logic]] and features such as [[Equality (mathematics)|equality]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 7}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=268–275}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=50–62}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 15}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Logical [[inference]] (or [[Deductive reasoning|deduction]]) is the process of [[logical proof|proving]] a new statement ([[Logical consequence|conclusion]]) from other statements that are already known to be true (the [[premise]]s).<ref name="Inference"> |

|||

[[Logical inference]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc = chpt. 10}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

A logical [[knowledge base]] also handles queries and assertions as a special case of inference.{{sfnp|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§8.3.1}} |

|||

An [[inference rule]] describes what is a [[validity (logic)|valid]] step in a proof. The most general inference rule is [[resolution (logic)|resolution]].<ref name="Resolution"> |

|||

[[Resolution (logic)|Resolution]] and [[unification (computer science)|unification]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc = §7.5.2, §9.2, §9.5}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Inference can be reduced to performing a search to find a path that leads from premises to conclusions, where each step is the application of an [[inference rule]].<ref name="Logic as search">[[Forward chaining]], [[backward chaining]], [[Horn clause]]s, and logical deduction as search: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc= §9.3, §9.4}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=~46–52}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=62–73}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 4.2, 7.2}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Inference performed this way is [[Intractable problem|intractable]] except for short proofs in restricted domains. No efficient, powerful and general method has been discovered. |

|||

[[Fuzzy logic]] assigns a "degree of truth" between 0 and 1. It can therefore handle propositions that are vague and partially true.<ref name="Fuzzy logic"> |

|||

Fuzzy logic: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|pp=214, 255, 459}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Scientific American|1999}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

[[Non-monotonic logic]]s are designed to handle [[default reasoning]].<ref name="Default reasoning and non-monotonic logic"/> |

|||

Other specialized versions of logic have been developed to describe many complex domains (see [[#Knowledge representation|knowledge representation]] above). |

|||

=== Probabilistic methods for uncertain reasoning === |

|||

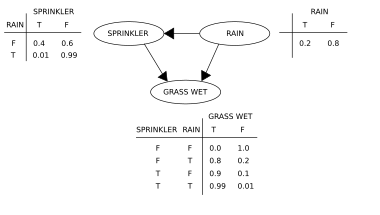

[[File:SimpleBayesNet.svg|thumb|380x380px|A simple [[Bayesian network]], with the associated [[Conditional probability table|conditional probability tables]]]] |

|||

Many problems in AI (including in reasoning, planning, learning, perception, and robotics) require the agent to operate with incomplete or uncertain information. AI researchers have devised a number of tools to solve these problems using methods from [[probability]] theory and economics.<ref name="Uncertain reasoning"> |

|||

Stochastic methods for uncertain reasoning: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Chpt. 12–18 and 20}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=345–395}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=165–191, 333–381}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 19}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

[[Bayesian network]]s<ref name="Bayesian networks"> |

|||

[[Bayesian network]]s: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§12.5–12.6, §13.4–13.5, §14.3–14.5, §16.5, §20.2 -20.3}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=361–381}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=~182–190, ≈363–379}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 19.3–4}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

are a very general tool that can be used for many problems, including [[automated reasoning|reasoning]] (using the [[Bayesian inference]] algorithm),{{efn| |

|||

Compared with symbolic logic, formal Bayesian inference is computationally expensive. For inference to be tractable, most observations must be [[conditionally independent]] of one another. [[Google AdSense|AdSense]] uses a Bayesian network with over 300 million edges to learn which ads to serve.{{sfnp|Domingos|2015|loc=chapter 6}} |

|||

}}<ref name="Bayesian inference"> |

|||

[[Bayesian inference]] algorithm: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§13.3–13.5}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=361–381}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Luger|Stubblefield|2004|pp=~363–379}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 19.4 & 7}} |

|||

</ref> [[Machine learning|learning]] (using the [[expectation-maximization algorithm]]),{{efn|Expectation-maximization, one of the most popular algorithms in machine learning, allows clustering in the presence of unknown [[latent variables]].{{sfnp|Domingos|2015|p=210}}}}<ref name="Bayesian learning"> |

|||

[[Bayesian learning]] and the [[expectation-maximization algorithm]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc = Chpt. 20}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=424–433}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Nilsson|1998|loc=chpt. 20}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Domingos|2015|p=210}} |

|||

</ref> [[Automated planning and scheduling|planning]] (using [[decision network]]s)<ref name="Bayesian decision networks">[[Bayesian decision theory]] and Bayesian [[decision network]]s: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§16.5}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

and [[Machine perception|perception]] (using [[dynamic Bayesian network]]s).<ref name="Stochastic temporal models"/> |

|||

Probabilistic algorithms can also be used for filtering, prediction, smoothing and finding explanations for streams of data, helping [[Machine perception|perception]] systems to analyze processes that occur over time (e.g., [[hidden Markov model]]s or [[Kalman filter]]s).<ref name="Stochastic temporal models"> |

|||

Stochastic temporal models: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Chpt. 14}} |

|||

[[Hidden Markov model]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§14.3}} |

|||

[[Kalman filter]]s: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§14.4}} |

|||

[[Dynamic Bayesian network]]s: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§14.5}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Precise mathematical tools have been developed that analyze how an agent can make choices and plan, using [[decision theory]], [[decision analysis]],<ref name="Decisions theory and analysis"> |

|||

[[decision theory]] and [[decision analysis]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=Chpt. 16–18}}, |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Poole|Mackworth|Goebel|1998|pp=381–394}} |

|||

</ref> and [[information value theory]].<ref name="Information value theory"> |

|||

[[Information value theory]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§16.6}} |

|||

</ref> These tools include models such as [[Markov decision process]]es,<ref name="Markov decision process">[[Markov decision process]]es and dynamic [[decision network]]s: |

|||

*{{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 17}} |

|||

</ref> dynamic [[decision network]]s,<ref name="Stochastic temporal models" /> [[game theory]] and [[mechanism design]].<ref name="Game theory and mechanism design">[[Game theory]] and [[mechanism design]]: |

|||

*{{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 18}} |

|||

</ref>[[File:EM_Clustering_of_Old_Faithful_data.gif|thumb|upright=1.2|[[Expectation-maximization]] [[Cluster analysis|clustering]] of [[Old Faithful]] eruption data starts from a random guess but then successfully converges on an accurate clustering of the two physically distinct modes of eruption.]] |

|||

=== Класификатори и статистичке методе учења === |

|||

The simplest AI applications can be divided into two types: classifiers (e.g., "if shiny then diamond"), on one hand, and controllers (e.g., "if diamond then pick up"), on the other hand. [[Classifier (mathematics)|Classifiers]]<ref name="Statistical classifiers"> |

|||

Statistical learning methods and [[Classifier (mathematics)|classifiers]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=chpt. 20}}, |

|||

</ref> |

|||

are functions that use [[pattern matching]] to determine the closest match. They can be fine-tuned based on chosen examples using [[supervised learning]]. Each pattern (also called an "[[random variate|observation]]") is labeled with a certain predefined class. All the observations combined with their class labels are known as a [[data set]]. When a new observation is received, that observation is classified based on previous experience.<ref name="Supervised learning"/> |

|||

There are many kinds of classifiers in use. The [[decision tree]] is the simplest and most widely used symbolic machine learning algorithm.<ref> |

|||

[[Alternating decision tree|Decision tree]]s: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§19.3}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Domingos|2015|p=88}} |

|||

</ref> [[K-nearest neighbor]] algorithm was the most widely used analogical AI until the mid-1990s, and [[Kernel methods]] such as the [[support vector machine]] (SVM) displaced k-nearest neighbor in the 1990s.<ref> |

|||

[[Nonparametric statistics|Non-parameteric]] learning models such as [[K-nearest neighbor]] and [[support vector machines]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§19.7}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Domingos|2015|p=187}} (k-nearest neighbor) |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Domingos|2015|p=88}} (kernel methods) |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The [[naive Bayes classifier]] is reportedly the "most widely used learner"{{sfnp|Domingos|2015|p=152}} at Google, due in part to its scalability.<ref> |

|||

[[Naive Bayes classifier]]: |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Russell|Norvig|2021|loc=§12.6}} |

|||

* {{Harvtxt|Domingos|2015|p=152}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

[[Artificial neural network|Neural networks]] are also used as classifiers.<ref name="Neural networks"/> |

|||

=== Вештачке неуронске мреже === |

|||

[[File:Artificial_neural_network.svg|right|thumb|A neural network is an interconnected group of nodes, akin to the vast network of [[neuron]]s in the [[human brain]].]] |

|||