Књижевност — разлика између измена

мНема описа измене |

. |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{bez_izvora}} |

|||

{{Књижевност}} |

{{Књижевност}} |

||

{{rut}} |

|||

'''Књижевност''', термин настао од речи [[књига]], представља превод стране речи литература и њен је најближи синоним. Термин '''литература''' потиче из [[латински језик|латинског језика]] од речи -{littero}- — [[слово]], настали превођењем [[грчки језик|грчке]] речи са истим значењем γραμματικη (τεχνη) од γραμμα — слово. |

'''Књижевност''', термин настао од речи [[књига]], представља превод стране речи литература и њен је најближи синоним. Термин '''литература''' потиче из [[латински језик|латинског језика]] од речи -{littero}- — [[слово]], настали превођењем [[грчки језик|грчке]] речи са истим значењем γραμματικη (τεχνη) од γραμμα — слово. |

||

| Ред 8: | Ред 8: | ||

Термин књижевност употребљава се да означи језичку уметност, естетички вид језичке творевине. Књижевна естетика покушава да пружи мерило за разликовање уметничке речи од осталих појавних облика [[језик]]а. Бројне су поделе књижевности и критеријуми на којима се те поделе заснивају: припадност одређеној епохи, периоду, правцу, етничкој заједници, културно-географском подручју; критеријум за поделу може бити и публика, коме је дело намењено; да ли је аутор познат или не. Полазећи од природе самог дела, књижевност се дели на књижевне родове и врсти. |

Термин књижевност употребљава се да означи језичку уметност, естетички вид језичке творевине. Књижевна естетика покушава да пружи мерило за разликовање уметничке речи од осталих појавних облика [[језик]]а. Бројне су поделе књижевности и критеријуми на којима се те поделе заснивају: припадност одређеној епохи, периоду, правцу, етничкој заједници, културно-географском подручју; критеријум за поделу може бити и публика, коме је дело намењено; да ли је аутор познат или не. Полазећи од природе самог дела, књижевност се дели на књижевне родове и врсти. |

||

== Definitions == |

|||

There have been various attempts to define "literature".<ref name=meyer>{{cite journal|last=Meyer|first=Jim|title=What is Literature? A Definition Based on Prototypes|journal=Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session|year=1997|volume=41|issue=1|url=http://www.und.nodak.edu/dept/linguistics/wp/1997Meyer.htm|accessdate=11 February 2014}}</ref> Simon and Delyse Ryan begin their attempt to answer the question "What is Literature?" with the observation: |

|||

<blockquote>The quest to discover a definition for "literature" is a road that is much travelled, though the point of arrival, if ever reached, is seldom satisfactory. Most attempted definitions are broad and vague, and they inevitably change over time. In fact, the only thing that is certain about defining literature is that the definition will change. Concepts of what is literature change over time as well. |

|||

<ref name=acu>{{cite web|title=What is Literature?|url=http://dlibrary.acu.edu.au/staffhome/siryan/academy/foundation/what_is_literature.htm|work=Foundation: Fundamentals of Literature and Drama|publisher=Australian Catholic University|accessdate=9 February 2014|author=Simon Ryan|author2=Delyse Ryan|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140220034442/http://dlibrary.acu.edu.au/staffhome/siryan/academy/foundation/what_is_literature.htm|archivedate=20 February 2014|df=}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Definitions of literature have varied over time: it is a "culturally relative definition".<ref name="Leitch ''et al.'', ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism'', 28">Leitch ''et al.'', ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism'', 28</ref> In [[Western Europe]] prior to the 18th century, literature denoted all books and writing.<ref name="Leitch ''et al.'', ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism'', 28" /> A more restricted sense of the term emerged during the [[Romanticism|Romantic period]], in which it began to demarcate "imaginative" writing.<ref name="Ross, The Emergence of Literature: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century, 406">Ross, "The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century", 406</ref><ref name="Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 16">Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 16</ref> Contemporary debates over what constitutes literature can be seen as returning to older, more inclusive notions; [[Cultural studies]], for instance, takes as its subject of analysis both popular and minority genres, in addition to [[Western canon|canonical works]]. |

|||

The [[value judgment]] definition of literature considers it to cover exclusively those writings that possess high quality or distinction, forming part of the so-called ''[[belles-lettres]]'' ('fine writing') tradition.<ref name="Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 9">Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 9</ref> This sort of definition is that used in the [[Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition|''Encyclopædia Britannica'' Eleventh Edition]] (1910–11) when it classifies literature as "the best expression of the best thought reduced to writing."<ref name="Biswas, ''Critique of Poetics'', 538">Biswas, ''Critique of Poetics'', 538</ref> Problematic in this view is that there is no objective definition of what constitutes "literature": anything can be literature, and anything which is universally regarded as literature has the potential to be excluded, since value judgments can change over time.<ref name="Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 9" /> |

|||

The [[Formalism (literature)|formalist]] definition is that "literature" foregrounds poetic effects; it is the "literariness" or "poetic" of literature that distinguishes it from ordinary speech or other kinds of writing (e.g., [[journalism]]).<ref name="Leitch ''et al.'', ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism'', 4">Leitch ''et al.'', ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism'', 4</ref><ref name="Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 2–6">Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 2–6</ref> Jim Meyer considers this a useful characteristic in explaining the use of the term to mean published material in a particular field (e.g., "[[scientific literature]]"), as such writing must use language according to particular standards.<ref name=meyer /> The problem with the formalist definition is that in order to say that literature deviates from ordinary uses of language, those uses must first be identified; this is difficult because "[[ordinary language]]" is an unstable category, differing according to social categories and across history.<ref name="Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 4">Eagleton, ''Literary theory: an introduction'', 4</ref> |

|||

[[Etymology|Etymologically]], the term derives from [[Latin language|Latin]] ''literatura/litteratura'' "learning, a writing, grammar," originally "writing formed with letters," from ''litera/littera'' "letter".<ref name=oetyd>{{cite web|title=literature (n.)|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=literature&allowed_in_frame=0|publisher=Online Etymology Dictionary|accessdate=9 February 2014}}</ref> In spite of this, the term has also been applied to [[Oral literature|spoken or sung texts]].<ref name=meyer /><ref>{{cite journal|last=Finnegan|first=Ruth|title=How Oral Is Oral Literature?|journal=Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies|year=1974|volume=37|issue=1|pages=52–64|jstor=614104|doi=10.1017/s0041977x00094842 }} {{subscription required}}</ref> |

|||

== Врсте књижевности == |

|||

Широко је усвојена подела књижевности на три рода: |

Широко је усвојена подела књижевности на три рода: |

||

| Ред 22: | Ред 37: | ||

Књижевност се може поделити на дуже историјскокњижевне временске одсеке, епохе: |

Књижевност се може поделити на дуже историјскокњижевне временске одсеке, епохе: |

||

{{colbegin|4}} |

|||

* [[Древни исток]] |

* [[Древни исток]] |

||

* [[Антика]] |

* [[Антика]] |

||

| Ред 39: | Ред 55: | ||

*# [[Касни модернизам]] |

*# [[Касни модернизам]] |

||

*# [[Постмодернизам]] |

*# [[Постмодернизам]] |

||

{{colend}} |

|||

=== Усмена књижевност === |

|||

Усмена књижевност представља најстарији облик књижевноумјетничког рада. На различитим просторима развијали су се различити родови усмене књижевности. Основна подела усмене књижевности на родове и врсте може изгледати овако: |

|||

{{colbegin|4}} |

|||

* Поезија |

|||

** лирска пјесма севдалинке, обредне, додолске, краљичке...; |

|||

** епска пјесма: епови и крајишнице; |

|||

** епско-лирска пјесма: баладе и романсе. |

|||

* Проза |

|||

** бајке, |

|||

** приповетке, |

|||

** приче, |

|||

** легенде, |

|||

** предаје: предаје о грађевинама, гробљима, турбетима; предаје о евлијама и керамети-сахибијама; предаје о значајним историјским догађајима; предаје о значајним историјским личностима... |

|||

* Драмски радови |

|||

{{colend}} |

|||

=== Писана или уметничка књижевност === |

|||

Уметничка књижевност, као и усмена, има три основне гране: поезију, прозу и драму. |

|||

==== Поезија ==== |

|||

{{Main article|Поезија}} |

|||

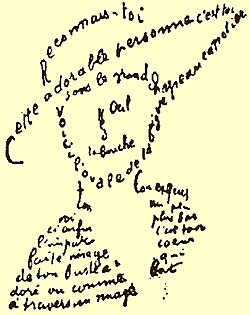

[[Датотека:Calligramme.jpg|thumb|right|250п|[[Калиграм]] [[Гијом Аполинер |Гијома Аполинера]]. Ово су типови поема у којима су написане речи аранжиране на такав начин да производе визуелну слику.]] |

|||

Поезија је врста књижевности у којој се текст пише у стиховима. Поезија обично садржи низ [[стилска фигура |стилских фигура]] укључујући риму, метафору, поређење, градацију, хиперболу, итд. Могуће је да је поезија најстарија врста књижевност. Рани примери су [[Сумер]]ски „[[Еп о Гилгамешу|Еп]] о [[Гилгамеш]]у” ([[1700. п. н. е.]]), делови Библије, и радови [[Хомер]]а. |

|||

Poetry is a form of literary art which uses [[Aesthetics|aesthetic]] and [[rhythm]]ic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, [[Prose|prosaic]] ostensible meaning.<ref name=oedpoetry>{{cite web|title=poetry, n.|url=http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/146552|work=Oxford English Dictionary|publisher=OUP|accessdate=13 February 2014}} {{subscription required}}</ref> Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from [[prose]] by its being set in [[Verse (poetry)|verse]];{{efn|This distinction is complicated by various hybrid forms such as the [[prose poem]]<ref name=prosepoemaap>{{cite web|title=Poetic Form: Prose Poem|url=http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/5787|work=Poets.org|publisher=Academy of American Poets|accessdate=15 February 2014}}</ref> and [[prosimetrum]],<ref name="Preminger, ''The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics'', 981">Preminger, ''The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics'', 981</ref> and more generally by the fact that prose possesses rhythm.<ref name="Preminger, ''The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics'', 979">Preminger, ''The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics'', 979</ref> Abram Lipsky refers to it as an "open secret" that "prose is not distinguished from poetry by lack of rhythm".<ref name=lipsky>{{cite journal|last=Lipsky|first=Abram|title=Rhythm in Prose|journal=The Sewanee Review|year=1908|volume=16|issue=3|pages=277–89|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/27530906|accessdate=15 February 2014}} {{subscription required}}</ref>}} prose is cast in [[Sentence (linguistics)|sentences]], poetry in [[Line (poetry)|lines]]; the [[syntax]] of prose is dictated by meaning, whereas that of poetry is held across meter or the visual aspects of the poem.<ref name="Preminger, ''The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics'', 938–9">Preminger, ''The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics'', 938–9</ref> Prior to the 19th century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines; accordingly, in 1658 a definition of poetry is "any kind of subject consisting of {{sic|hide=y|Rythm}} or Verses".<ref name=oedpoetry /> Possibly as a result of [[Aristotle]]'s influence (his ''[[Poetics (Aristotle)|Poetics]]''), "poetry" before the 19th century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art.<ref name="Ross, The Emergence of Literature: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century, 398">Ross, "The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century", 398</ref> As a form it may pre-date [[literacy]], with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition;<ref>{{cite book|last=Finnegan|first=Ruth H.|title=Oral poetry: its nature, significance, and social context|year=1977|publisher=Indiana University Press|page=66}}</ref><ref name=magoun>{{cite journal|last=Magoun, Jr.|first=Francis P.|title=Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry|journal=Speculum|year=1953|volume=28|issue=3|pages=446–67|jstor=2847021|doi=10.2307/2847021}} {{subscription required}}</ref> hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature. |

|||

У различитим нацијама наилази се на раличите врсте поезије. У грчкој поезији стихови се ретко римују, док је у Италијанској и Француској поезији супротан случај. Генерално гледајући, у британској и немачкој поезији рима је подједнако и присутна и одсутна. Неке језике карактерише природан афинитет за дуже стихове, док је код других изражена тенденција ка краћим стиховима. Неке од ових карактеристика су условљене разликама у лексици и граматици самих језика. На пример, неки језици имају већи фонд речи које се римују, или више синонима од других. Поезија је такође укомпонована у неке врсте драме, попут опере. |

|||

==== Проза ==== |

|||

{{Main article|Проза}} |

|||

Проза је форма [[језик]]а која поседује обичну [[синтакса |синтаксу]] и [[природни говор]] уместо ритмичке структуре; in which regard, along with its measurement in sentences rather than lines, it differs from poetry.<ref name="Preminger, ''The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics'', 938–9" /><ref>{{cite web|title=Glossary: P|url=http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/litweb10/glossary/P.aspx|work=LitWeb, the Norton Introduction to Literature Studyspace|accessdate=15 February 2014|author=Alison Booth|author2=Kelly J. Mays }}</ref> On the historical development of prose, Richard Graff notes that "[In the case of [[Ancient Greece]]] recent scholarship has emphasized the fact that formal prose was a comparatively late development, an "invention" properly associated with the [[Classical antiquity|classical period]]".<ref name=graff>{{cite journal|last=Graff|first=Richard|title=Prose versus Poetry in Early Greek Theories of Style|journal=Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric|year=2005|volume=23|issue=4|pages=303–35|jstor=10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303|doi=10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303}} {{subscription required}}</ref> |

|||

*'''[[Novel]]''': a long [[fiction]]al prose narrative. It was the form's close relation to [[Realism (arts)|real life]] that differentiated it from the [[chivalric romance]];<ref name="Goody, ''The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture'', 18">{{cite book|last=Goody|first=Jack|title=The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography, and Culture|year=2006|publisher=Princeton UP|location=Princeton|isbn=978-0-691-04947-2|page=18|editor=Franco Moretti|chapter=From Oral to Written: An Anthropological Breakthrough in Storytelling}}</ref><ref name=brooklyn>{{cite web|title=The Novel|url=http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/english/melani/cs6/novel.html|work=A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature|publisher=[[Brooklyn College]]|accessdate=22 February 2014}}</ref> in most European languages the equivalent term is ''roman'', indicating the proximity of the forms.<ref name=brooklyn /> In English, the term emerged from the [[Romance language]]s in the late 15th century, with the meaning of "news"; it came to indicate something new, without a distinction between fact or fiction.<ref name=sommerville>{{cite book|last=Sommerville|first=C. J.|year=1996|title=The News Revolution in England: Cultural Dynamics of Daily Information|location=Oxford|publisher=OUP|page=18}}</ref> Although there are many historical prototypes, so-called "novels before the novel",<ref name="Goody, ''The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture'', 19">Goody, ''The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture'', 19</ref> the modern novel form emerges late in cultural history—roughly during the eighteenth century.<ref name="Goody, ''The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture'', 20">Goody, ''The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture'', 20</ref> Initially subject to much criticism, the novel has acquired a dominant position amongst literary forms, both popularly and critically.<ref name=brooklyn /><ref name="Goody, ''The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture'', 29">Goody, ''The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture'', 29</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The Novel, Volume 2: Forms and Themes|year=2006|publisher=Princeton UP|location=Princeton|isbn=978-0-691-04948-9|page=31|editor=Franco Moretti|chapter=The Novel in Search of Itself: A Historical Morphology}}</ref> |

|||

*'''[[Novella]]''': in purely quantitative terms, the novella exists between the novel and short story; the publisher [[Melville House Publishing|Melville House]] classifies it as "too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story".<ref name=antrim>{{cite web|last=Antrim|first=Taylor|title=In Praise of Short|url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2010/08/04/the-novella-is-making-a-comeback.html|publisher=[[The Daily Beast]]|accessdate=15 February 2014|year=2010}}</ref> There is no precise definition in terms of word or page count.<ref name="Giraldi 796">Giraldi 796</ref> [[Literary prize]]s and [[Publishing|publishing houses]] often have their own arbitrary limits,<ref name=ripatrazone>{{cite web|last=Ripatrazone|first=Nick|title=Taut, Not Trite: On the Novella|url=http://www.themillions.com/2013/09/taut-not-trite-on-the-novella.html|publisher=[[The Millions]]|accessdate=15 February 2014}}</ref> which vary according to their particular intentions. Summarizing the variable definitions of the novella, William Giraldi concludes "[it is a form] whose identity seems destined to be disputed into perpetuity".<ref name="Giraldi 793">Giraldi 793</ref> It has been suggested that the size restriction of the form produces various stylistic results, both some that are shared with the novel or short story,<ref name="Giraldi 795–6">Giraldi 795–6</ref><ref name=fetherling>{{cite web |last=Fetherling |first=George |title=Briefly, the case for the novella |url=http://www.sevenoaksmag.com/commentary/94_comm1.html |publisher=Seven Oaks Magazine |accessdate=15 February 2014 |year=2006 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://archive.li/20120912031610/http://www.sevenoaksmag.com/commentary/94_comm1.html |archivedate=12 September 2012 |df= }}</ref> and others unique to the form.<ref name=nortonolm>{{cite web|last=Norton|first=Ingrid|title=Of Form, E-Readers, and Thwarted Genius: End of a Year with Short Novels|url=http://www.openlettersmonthly.com/of-form-e-readers-and-thwarted-genius-end-of-a-year-with-short-novels/|publisher=[[Open Letters Monthly]]|accessdate=15 February 2014}}</ref> |

|||

*'''[[Short story]]''': a dilemma in defining the "short story" as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative; hence it also has a contested origin,<ref name=boyd>{{cite web|last=Boyd|first=William|title=A short history of the short story|url=http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/william-boyd-short-history-of-the-short-story/#.Uxr1EoVVO-c|publisher=Prospect Magazine|accessdate=8 March 2014}}</ref> variably suggested as the earliest short narratives (e.g. the [[Bible]]), early short story writers (e.g. [[Edgar Allan Poe]]), or the clearly modern short story writers (e.g. [[Anton Chekhov]]).<ref name=colibaba>{{cite journal|last=Colibaba|first=Ştefan|title=The Nature of the Short Story: Attempts at Definition|journal=Synergy|year=2010|volume=6|issue=2|pages=220–230|url=http://synergy.ase.ro/issues/2010-vol6-no2/14-the-nature-of-the-short-story-attempts-at-definition.pdf|accessdate=6 March 2014}}</ref> Apart from its distinct size, various theorists have suggested that the short story has a characteristic subject matter or structure;<ref name=rohrberger>{{cite journal|last=Rohrberger|first=Mary|author2=Dan E. Burns |title=Short Fiction and the Numinous Realm: Another Attempt at Definition|journal=Modern Fiction Studies|year=1982|volume=XXVIII|issue=6}}</ref><ref name=may>{{cite book|last=May|first=Charles|title=The Short Story. The Reality of Artifice|year=1995|publisher=Twain|location=New York}}</ref> these discussions often position the form in some relation to the novel.<ref name=pratt>{{cite book|year=1994|publisher=Ohio UP|location=Athens|author=Marie Louise Pratt|editor=Charles May|title=The Short Story: The Long and the Short of It}}</ref> |

|||

==== Драма ==== |

|||

Драма је врста књижевности која је настала за време античке Грчке и развија се до дан данас. Драма се у главном не пише да би била читана већ да би била приказана у позоришту.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Elam|first1=Kier|title=The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama|date=1980|publisher=Methuen|location=London and New York|isbn=0-416-72060-9|page=98}}</ref> Током осамнестог и деветнестог века, [[опера]] је настала као комбинација драме, поезије, и [[музика|музике]]. |

|||

Основне врсте драме су [[трагедија]] и [[комедија]], које се прво појављују неколико векова пре нове ере. Старогрчка драма је, по легенди, настала за време верског фестивала, када се један певач одвојио од хора и почео певати сам. Грчка трагедија се углавном бавила са познатим историјским и [[Митологија|митолошким]] темама. Трагедије су (као што су то и данас) типично биле озбиљне и тицале су се се људске природе. За разлику од њих, комедије су већомом биле сатиричне и увијек су имале сретан завршетак. Грчки фестивали би обично имали три трагедије и једну комедију. |

|||

== Напомене == |

|||

{{notelist}} |

|||

== Референце == |

|||

{{reflist|30em}} |

|||

== Литература == |

|||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Critique of Poetics (vol. 2)|year=2005|publisher=Atlantic Publishers & Dist|isbn=978-81-269-0377-1|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9dpqORJYizkC&lpg=PA538&ots=BMT4tPWAWw&dq=%22the%20best%20expression%20of%20the%20best%20thought%20reduced%20to%20writing%22&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false|author=A.R. Biswas}} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=The literature of ancient Sumer|year=2006|publisher=OUP|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-929633-0|editor1=Jeremy Black |editor2=Graham Cunningham |editor3=Eleanor Robson }} |

|||

* {{cite book|title=The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism|year=2001|publisher=Norton|isbn=0-393-97429-4|first1=William E.|last1=Cain|first2=Laurie A.|last2=Finke|first3=Barbara E.|last3=Johnson|first4=John|last4= McGowan|first5=Jeffrey J.|last5=Williams|editor=Vincent B. Leitch}} |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Eagleton|first=Terry|title=Literary theory: an introduction: anniversary edition|year=2008|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|location=Oxford|isbn=978-1-4051-7921-8|edition=Anniversary, 2nd}} |

|||

* {{citation |last=Foster |first=John Lawrence |title=Ancient Egyptian Literature: An Anthology |year=2001 |publisher=University of Texas Press |location=Austin |pages=xx| isbn=0-292-72527-2}} |

|||

* {{cite journal|last=Giraldi|first=William|title=The Novella's Long Life|journal=The Southern Review|issue=Autumn 2008|pages=793–801|url=http://williamgiraldi.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/novella1.pdf|accessdate=15 February 2014|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140222222151/http://williamgiraldi.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/novella1.pdf|archivedate=22 February 2014|df=}} |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Goody|first=Jack|title=The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography, and Culture|year=2006|publisher=Princeton UP|location=Princeton|isbn=978-0-691-04947-2|page=18|editor=Franco Moretti|chapter=From Oral to Written: An Anthropological Breakthrough in Storytelling}} |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Preminger|first=Alex|title=The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics|publisher=US: Princeton University Press|year=1993|isbn=0-691-02123-6|display-authors=etal}} |

|||

* {{cite journal|last=Ross|first=Trevor|title=The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century."|journal=ELH|year=1996|volume=63|pages=397–422|url=https://www.ualberta.ca/~dmiall/MakingReaders/Readings/Ross%20English%20Canon.pdf|accessdate=9 February 2014|doi=10.1353/elh.1996.0019}} |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Bonheim|first=Helmut|title=The Narrative Modes: Techniques of the Short Story|year=1982|publisher=Brewer|location=Cambridge}} An overview of several hundred short stories. |

|||

* {{cite journal|last=Gillespie|first=Gerald|title=Novella, nouvelle, novella, short novel? — A review of terms|journal=Neophilologus|date=January 1967|volume=51|issue=1|pages=117–127|doi=10.1007/BF01511303|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF01511303?LI=true#page-1|accessdate=6 March 2014}} {{subscription required}} |

|||

* {{cite web|last=Wheeler|first=L. Kip|title=Periods of Literary History|url=http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/documents/periods_lit_history.pdf|publisher=[[Carson-Newman University]]|accessdate=18 March 2014}} Brief summary of major periods in literary history of the Western tradition. |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Други пројекти|commons=Literature|wikinews=Књижевност}} |

{{Други пројекти|commons=Literature|wikinews=Књижевност}} |

||

* -{[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg Online Library]}- |

|||

** -{[http://www.abacci.com/books/default.asp Abacci]}- |

|||

* -{[http://www.iblist.com/ Internet Book List]}- |

|||

* -{[https://archive.org/details/texts Internet Archive Digital eBook Collection]}- |

|||

{{Хуманитарне науке}} |

{{Хуманитарне науке}} |

||

{{Subject bar |wikt=yes |wikt-search=literature |commons=yes |commons-search=Category:Literature |n=yes |n-search=Category:Literature |q=yes |s=yes |s-search=Category:Literature |b=yes |b-search=Subject:Literature |v=yes |d=yes |d-search=Q8242}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Категорија:Књижевност|*]] |

[[Категорија:Књижевност|*]] |

||

Верзија на датум 13. септембар 2017. у 02:59

| Књижевност |

|---|

|

| Главни облици |

| Жанрови |

| Медији |

| Технике |

| Историја и спискови |

| Расправа |

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Књижевност, термин настао од речи књига, представља превод стране речи литература и њен је најближи синоним. Термин литература потиче из латинског језика од речи littero — слово, настали превођењем грчке речи са истим значењем γραμματικη (τεχνη) од γραμμα — слово.

Народна књижевност представља дела стварана вековима, у којима се описује колективни став народа чијој народној књижевности дело припада. Уметничка књижевност садржи песничке слике изражене речима. Она представља објективну стварност, али виђену очима уметника. Садржи мисли и осећања писца, а код читаоца изазива одређена осећања и расположења.

Термин књижевност употребљен у ужем значењу означава уметничку књижевност (белетристика, лепа књижевност). Употребљен у ширем значењу, термин књижевност односи се и на дела настала у процесу проучавања књижевности, односно обухвата и текстове који припадају књижевној критици, књижевној историји и теорији књижевности, које заједно са методологијом проучавања књижевности конституишу науку о књижевности.

Термин књижевност употребљава се да означи језичку уметност, естетички вид језичке творевине. Књижевна естетика покушава да пружи мерило за разликовање уметничке речи од осталих појавних облика језика. Бројне су поделе књижевности и критеријуми на којима се те поделе заснивају: припадност одређеној епохи, периоду, правцу, етничкој заједници, културно-географском подручју; критеријум за поделу може бити и публика, коме је дело намењено; да ли је аутор познат или не. Полазећи од природе самог дела, књижевност се дели на књижевне родове и врсти.

Definitions

There have been various attempts to define "literature".[1] Simon and Delyse Ryan begin their attempt to answer the question "What is Literature?" with the observation:

The quest to discover a definition for "literature" is a road that is much travelled, though the point of arrival, if ever reached, is seldom satisfactory. Most attempted definitions are broad and vague, and they inevitably change over time. In fact, the only thing that is certain about defining literature is that the definition will change. Concepts of what is literature change over time as well. [2]

Definitions of literature have varied over time: it is a "culturally relative definition".[3] In Western Europe prior to the 18th century, literature denoted all books and writing.[3] A more restricted sense of the term emerged during the Romantic period, in which it began to demarcate "imaginative" writing.[4][5] Contemporary debates over what constitutes literature can be seen as returning to older, more inclusive notions; Cultural studies, for instance, takes as its subject of analysis both popular and minority genres, in addition to canonical works.

The value judgment definition of literature considers it to cover exclusively those writings that possess high quality or distinction, forming part of the so-called belles-lettres ('fine writing') tradition.[6] This sort of definition is that used in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1910–11) when it classifies literature as "the best expression of the best thought reduced to writing."[7] Problematic in this view is that there is no objective definition of what constitutes "literature": anything can be literature, and anything which is universally regarded as literature has the potential to be excluded, since value judgments can change over time.[6]

The formalist definition is that "literature" foregrounds poetic effects; it is the "literariness" or "poetic" of literature that distinguishes it from ordinary speech or other kinds of writing (e.g., journalism).[8][9] Jim Meyer considers this a useful characteristic in explaining the use of the term to mean published material in a particular field (e.g., "scientific literature"), as such writing must use language according to particular standards.[1] The problem with the formalist definition is that in order to say that literature deviates from ordinary uses of language, those uses must first be identified; this is difficult because "ordinary language" is an unstable category, differing according to social categories and across history.[10]

Etymologically, the term derives from Latin literatura/litteratura "learning, a writing, grammar," originally "writing formed with letters," from litera/littera "letter".[11] In spite of this, the term has also been applied to spoken or sung texts.[1][12]

Врсте књижевности

Широко је усвојена подела књижевности на три рода:

- лирика, коју одликује субјективност (осечања, мишљења песника)

- епика, коју одликује објективност (опис радње) и епски ликови

- драма, коју одликују дијалог, као и посебан стил писања

Књижевност се може делити и на:

- поезију, где је текст обично подељен на строфе и стихове

- прозу, где текст није никако ограничен,

- драму, стил писања код драме као рода (указује се на ликове који говоре)

Књижевност се најпре стварала и преносила усменим путем. Та врста књижевности назива се усменом или народном књижевношћу. Од самих својих почетака књижевност је у вези са митом и религијом. Стварајући митове, човек је покушавао да објасни свет који га је окруживао. Са развојем критичке свести човек постепено престаје да верује у митове и митске приче. Тог тренутка мит постаје књижевност.

Књижевност се може поделити на дуже историјскокњижевне временске одсеке, епохе:

Усмена књижевност

Усмена књижевност представља најстарији облик књижевноумјетничког рада. На различитим просторима развијали су се различити родови усмене књижевности. Основна подела усмене књижевности на родове и врсте може изгледати овако:

- Поезија

- лирска пјесма севдалинке, обредне, додолске, краљичке...;

- епска пјесма: епови и крајишнице;

- епско-лирска пјесма: баладе и романсе.

- Проза

- бајке,

- приповетке,

- приче,

- легенде,

- предаје: предаје о грађевинама, гробљима, турбетима; предаје о евлијама и керамети-сахибијама; предаје о значајним историјским догађајима; предаје о значајним историјским личностима...

- Драмски радови

Писана или уметничка књижевност

Уметничка књижевност, као и усмена, има три основне гране: поезију, прозу и драму.

Поезија

Поезија је врста књижевности у којој се текст пише у стиховима. Поезија обично садржи низ стилских фигура укључујући риму, метафору, поређење, градацију, хиперболу, итд. Могуће је да је поезија најстарија врста књижевност. Рани примери су Сумерски „Еп о Гилгамешу” (1700. п. н. е.), делови Библије, и радови Хомера.

Poetry is a form of literary art which uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, prosaic ostensible meaning.[13] Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from prose by its being set in verse;[а] prose is cast in sentences, poetry in lines; the syntax of prose is dictated by meaning, whereas that of poetry is held across meter or the visual aspects of the poem.[18] Prior to the 19th century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines; accordingly, in 1658 a definition of poetry is "any kind of subject consisting of Rythm or Verses".[13] Possibly as a result of Aristotle's influence (his Poetics), "poetry" before the 19th century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art.[19] As a form it may pre-date literacy, with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition;[20][21] hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature.

У различитим нацијама наилази се на раличите врсте поезије. У грчкој поезији стихови се ретко римују, док је у Италијанској и Француској поезији супротан случај. Генерално гледајући, у британској и немачкој поезији рима је подједнако и присутна и одсутна. Неке језике карактерише природан афинитет за дуже стихове, док је код других изражена тенденција ка краћим стиховима. Неке од ових карактеристика су условљене разликама у лексици и граматици самих језика. На пример, неки језици имају већи фонд речи које се римују, или више синонима од других. Поезија је такође укомпонована у неке врсте драме, попут опере.

Проза

Проза је форма језика која поседује обичну синтаксу и природни говор уместо ритмичке структуре; in which regard, along with its measurement in sentences rather than lines, it differs from poetry.[18][22] On the historical development of prose, Richard Graff notes that "[In the case of Ancient Greece] recent scholarship has emphasized the fact that formal prose was a comparatively late development, an "invention" properly associated with the classical period".[23]

- Novel: a long fictional prose narrative. It was the form's close relation to real life that differentiated it from the chivalric romance;[24][25] in most European languages the equivalent term is roman, indicating the proximity of the forms.[25] In English, the term emerged from the Romance languages in the late 15th century, with the meaning of "news"; it came to indicate something new, without a distinction between fact or fiction.[26] Although there are many historical prototypes, so-called "novels before the novel",[27] the modern novel form emerges late in cultural history—roughly during the eighteenth century.[28] Initially subject to much criticism, the novel has acquired a dominant position amongst literary forms, both popularly and critically.[25][29][30]

- Novella: in purely quantitative terms, the novella exists between the novel and short story; the publisher Melville House classifies it as "too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story".[31] There is no precise definition in terms of word or page count.[32] Literary prizes and publishing houses often have their own arbitrary limits,[33] which vary according to their particular intentions. Summarizing the variable definitions of the novella, William Giraldi concludes "[it is a form] whose identity seems destined to be disputed into perpetuity".[34] It has been suggested that the size restriction of the form produces various stylistic results, both some that are shared with the novel or short story,[35][36] and others unique to the form.[37]

- Short story: a dilemma in defining the "short story" as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative; hence it also has a contested origin,[38] variably suggested as the earliest short narratives (e.g. the Bible), early short story writers (e.g. Edgar Allan Poe), or the clearly modern short story writers (e.g. Anton Chekhov).[39] Apart from its distinct size, various theorists have suggested that the short story has a characteristic subject matter or structure;[40][41] these discussions often position the form in some relation to the novel.[42]

Драма

Драма је врста књижевности која је настала за време античке Грчке и развија се до дан данас. Драма се у главном не пише да би била читана већ да би била приказана у позоришту.[43] Током осамнестог и деветнестог века, опера је настала као комбинација драме, поезије, и музике.

Основне врсте драме су трагедија и комедија, које се прво појављују неколико векова пре нове ере. Старогрчка драма је, по легенди, настала за време верског фестивала, када се један певач одвојио од хора и почео певати сам. Грчка трагедија се углавном бавила са познатим историјским и митолошким темама. Трагедије су (као што су то и данас) типично биле озбиљне и тицале су се се људске природе. За разлику од њих, комедије су већомом биле сатиричне и увијек су имале сретан завршетак. Грчки фестивали би обично имали три трагедије и једну комедију.

Напомене

- ^ This distinction is complicated by various hybrid forms such as the prose poem[14] and prosimetrum,[15] and more generally by the fact that prose possesses rhythm.[16] Abram Lipsky refers to it as an "open secret" that "prose is not distinguished from poetry by lack of rhythm".[17]

Референце

- ^ а б в Meyer, Jim (1997). „What is Literature? A Definition Based on Prototypes”. Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session. 41 (1). Приступљено 11. 2. 2014.

- ^ Simon Ryan; Delyse Ryan. „What is Literature?”. Foundation: Fundamentals of Literature and Drama. Australian Catholic University. Архивирано из оригинала 20. 2. 2014. г. Приступљено 9. 2. 2014.

- ^ а б Leitch et al., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 28

- ^ Ross, "The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century", 406

- ^ Eagleton, Literary theory: an introduction, 16

- ^ а б Eagleton, Literary theory: an introduction, 9

- ^ Biswas, Critique of Poetics, 538

- ^ Leitch et al., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 4

- ^ Eagleton, Literary theory: an introduction, 2–6

- ^ Eagleton, Literary theory: an introduction, 4

- ^ „literature (n.)”. Online Etymology Dictionary. Приступљено 9. 2. 2014.

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (1974). „How Oral Is Oral Literature?”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 37 (1): 52—64. JSTOR 614104. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00094842. (потребна претплата)

- ^ а б „poetry, n.”. Oxford English Dictionary. OUP. Приступљено 13. 2. 2014. (потребна претплата)

- ^ „Poetic Form: Prose Poem”. Poets.org. Academy of American Poets. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014.

- ^ Preminger, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 981

- ^ Preminger, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 979

- ^ Lipsky, Abram (1908). „Rhythm in Prose”. The Sewanee Review. 16 (3): 277—89. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014. (потребна претплата)

- ^ а б Preminger, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 938–9

- ^ Ross, "The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century", 398

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth H. (1977). Oral poetry: its nature, significance, and social context. Indiana University Press. стр. 66.

- ^ Magoun, Jr., Francis P. (1953). „Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry”. Speculum. 28 (3): 446—67. JSTOR 2847021. doi:10.2307/2847021. (потребна претплата)

- ^ Alison Booth; Kelly J. Mays. „Glossary: P”. LitWeb, the Norton Introduction to Literature Studyspace. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014.

- ^ Graff, Richard (2005). „Prose versus Poetry in Early Greek Theories of Style”. Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 23 (4): 303—35. JSTOR 10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303. doi:10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303. (потребна претплата)

- ^ Goody, Jack (2006). „From Oral to Written: An Anthropological Breakthrough in Storytelling”. Ур.: Franco Moretti. The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography, and Culture. Princeton: Princeton UP. стр. 18. ISBN 978-0-691-04947-2.

- ^ а б в „The Novel”. A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature. Brooklyn College. Приступљено 22. 2. 2014.

- ^ Sommerville, C. J. (1996). The News Revolution in England: Cultural Dynamics of Daily Information. Oxford: OUP. стр. 18.

- ^ Goody, The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture, 19

- ^ Goody, The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture, 20

- ^ Goody, The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture, 29

- ^ Franco Moretti, ур. (2006). „The Novel in Search of Itself: A Historical Morphology”. The Novel, Volume 2: Forms and Themes. Princeton: Princeton UP. стр. 31. ISBN 978-0-691-04948-9.

- ^ Antrim, Taylor (2010). „In Praise of Short”. The Daily Beast. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014.

- ^ Giraldi 796

- ^ Ripatrazone, Nick. „Taut, Not Trite: On the Novella”. The Millions. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014.

- ^ Giraldi 793

- ^ Giraldi 795–6

- ^ Fetherling, George (2006). „Briefly, the case for the novella”. Seven Oaks Magazine. Архивирано из оригинала 12. 9. 2012. г. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014.

- ^ Norton, Ingrid. „Of Form, E-Readers, and Thwarted Genius: End of a Year with Short Novels”. Open Letters Monthly. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014.

- ^ Boyd, William. „A short history of the short story”. Prospect Magazine. Приступљено 8. 3. 2014.

- ^ Colibaba, Ştefan (2010). „The Nature of the Short Story: Attempts at Definition” (PDF). Synergy. 6 (2): 220—230. Приступљено 6. 3. 2014.

- ^ Rohrberger, Mary; Dan E. Burns (1982). „Short Fiction and the Numinous Realm: Another Attempt at Definition”. Modern Fiction Studies. XXVIII (6).

- ^ May, Charles (1995). The Short Story. The Reality of Artifice. New York: Twain.

- ^ Marie Louise Pratt (1994). Charles May, ур. The Short Story: The Long and the Short of It. Athens: Ohio UP.

- ^ Elam, Kier (1980). The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. London and New York: Methuen. стр. 98. ISBN 0-416-72060-9.

Литература

- A.R. Biswas (2005). Critique of Poetics (vol. 2). Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0377-1.

- Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson, ур. (2006). The literature of ancient Sumer. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0.

- Cain, William E.; Finke, Laurie A.; Johnson, Barbara E.; McGowan, John; Williams, Jeffrey J. (2001). Vincent B. Leitch, ур. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97429-4.

- Eagleton, Terry (2008). Literary theory: an introduction: anniversary edition (Anniversary, 2nd изд.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-7921-8.

- Foster, John Lawrence (2001), Ancient Egyptian Literature: An Anthology, Austin: University of Texas Press, стр. xx, ISBN 0-292-72527-2

- Giraldi, William. „The Novella's Long Life” (PDF). The Southern Review (Autumn 2008): 793—801. Архивирано из оригинала (PDF) 22. 2. 2014. г. Приступљено 15. 2. 2014.

- Goody, Jack (2006). „From Oral to Written: An Anthropological Breakthrough in Storytelling”. Ур.: Franco Moretti. The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography, and Culture. Princeton: Princeton UP. стр. 18. ISBN 978-0-691-04947-2.

- Preminger, Alex; et al. (1993). The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02123-6.

- Ross, Trevor (1996). „The Emergence of "Literature": Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century."” (PDF). ELH. 63: 397—422. doi:10.1353/elh.1996.0019. Приступљено 9. 2. 2014.

- Bonheim, Helmut (1982). The Narrative Modes: Techniques of the Short Story. Cambridge: Brewer. An overview of several hundred short stories.

- Gillespie, Gerald (јануар 1967). „Novella, nouvelle, novella, short novel? — A review of terms”. Neophilologus. 51 (1): 117—127. doi:10.1007/BF01511303. Приступљено 6. 3. 2014. (потребна претплата)

- Wheeler, L. Kip. „Periods of Literary History” (PDF). Carson-Newman University. Приступљено 18. 3. 2014. Brief summary of major periods in literary history of the Western tradition.