Савет Европске уније — разлика између измена

м Инфокутија, председавајућа држава ознаке: Визуелно уређивање мобилна измена мобилно веб-уређивање напредна мобилна измена |

. ознака: везе до вишезначних одредница |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{short description|Институција Европске уније}} |

|||

{{Разликовати|[[Европски савет]]ом|[[Савет Европе|Саветом Европе]]}} |

{{Разликовати|[[Европски савет]]ом|[[Савет Европе|Саветом Европе]]}} |

||

{{Инфокутија Организација |

{{Инфокутија Организација |

||

| Ред 17: | Ред 18: | ||

| веб_страница = {{URL|www.consilium.europa.eu}}}} |

| веб_страница = {{URL|www.consilium.europa.eu}}}} |

||

[[File:Europa building February 2016.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Зграда ''Европа'' у Бриселу]] |

[[File:Europa building February 2016.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Зграда ''Европа'' у Бриселу]] |

||

{{Политика Европске уније}} |

{{Политика Европске уније}} |

||

'''Савет Европске уније''' или '''Савет министара Европске уније''' је главни орган за доношење одлука у [[Европска унија|Европској унији]]. Оличење је земаља чланица, чије представнике окупља регуларно на министарском нивоу. |

|||

'''Савет Европске уније''' или '''Савет министара Европске уније''' је главни орган за доношење одлука у [[Европска унија|Европској унији]]. Оличење је земаља чланица, чије представнике окупља регуларно на министарском нивоу. На основу дневног реда, Савет се састаје у различитом саставу: инострани послови, финансије, образовање, телекомуникације итд.<ref name="eur-lex.europa.eu">{{cite web|url=http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:C:2016:202:TOC|title=EUR-Lex - C:2016:202:TOC - EN - EUR-Lex|website=eur-lex.europa.eu}}</ref> То је једно од два [[legislature of the European Union|законодавна тела]] и заједно са [[European Parliament|Европским парламентом]] служи за измену и одобравање или улагање вета на предлоге [[European Commission|Европске комисије]], која има [[right of initiative (legislative)|право иницијативе]].<ref name="auto1">{{cite web|url=http://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/en/powers-and-procedures/legislative-powers|work=European Parliament|title=Legislative powers|access-date=13 February 2019}}</ref><ref name="Library of European Parliament">{{cite web|url=http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/bibliotheque/briefing/2013/130619/LDM_BRI(2013)130619_REV2_EN.pdf|work=Library of the European Parliament|title=Parliament's legislative initiative|date=24 October 2013|access-date=13 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140319173632/http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/bibliotheque/briefing/2013/130619/LDM_BRI%282013%29130619_REV2_EN.pdf|archive-date=19 March 2014|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{cite web|url=https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law_en|work=European Commission|title=Planning and proposing law|date=20 April 2019}}</ref> |

|||

На основу дневног реда, Савет се састаје у различитом саставу: инострани послови, финансије, образовање, телекомуникације итд. |

|||

Савет има известан број обавеза: |

Савет има известан број обавеза: |

||

| Ред 31: | Ред 30: | ||

# Координира активностима земаља чланица и усваја мерила у полицијској и правосудној сарадњи у питањима криминала |

# Координира активностима земаља чланица и усваја мерила у полицијској и правосудној сарадњи у питањима криминала |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Седиште Савета је у [[Брисел]]у. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

== Председништво Савета Европске уније == |

== Председништво Савета Европске уније == |

||

| Ред 79: | Ред 76: | ||

| [[Португалија]], [[Словенија]] |

| [[Португалија]], [[Словенија]] |

||

|}</center> |

|}</center> |

||

== Састав == |

|||

{{рут}} |

|||

The [[Presidency of the Council of the European Union|Presidency]] of the Council rotates every six months among the governments of EU member states, with the relevant ministers of the respective country holding the Presidency at any given time ensuring the smooth running of the meetings and setting the daily agenda.<ref name="Consilium - Council"/> The continuity between presidencies is provided by an arrangement under which three successive presidencies, known as ''Presidency trios'', share common political programmes. The [[Foreign Affairs Council]] (national foreign ministers) is however chaired by the Union's [[High Representative]].<ref name="Const Info">{{cite web|title=The Union's institutions: The Council of Ministers|publisher=[[Europa (web portal)]]|url=http://europa.eu/scadplus/constitution/council_en.htm|access-date=1 July 2007}}</ref> |

|||

Its decisions are made by [[qualified majority voting]] in most areas, unanimity in others, or just simple majority for procedural issues. Usually where it operates unanimously, it only needs to consult the Parliament. However, in most areas the [[ordinary legislative procedure]] applies meaning both Council and Parliament share legislative and budgetary powers equally, meaning both have to agree for a proposal to pass. In a few limited areas the Council may initiate new [[European Union law|EU law]] itself.<ref name="Consilium - Council">{{cite web|publisher=[[Europa (web portal)|Council of the European Union]]|title = Council of the European Union|date = 16 June 2016|url=https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions-bodies/council-eu_en|access-date = 19 February 2017}}</ref> |

|||

== Историја == |

|||

The Council first appeared in the [[European Coal and Steel Community]] (ECSC) as the "Special Council of Ministers", set up to counterbalance the High Authority (the supranational executive, now the Commission). The original Council had limited powers: issues relating only to coal and steel were in the Authority's domain, and the Council's consent was only required on decisions outside coal and steel. As a whole, the Council only scrutinised the [[High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community|High Authority]] (the executive). In 1957, the [[Treaties of Rome]] established two new communities, and with them two new Councils: the Council of the [[European Atomic Energy Community]] (EAEC) and the Council of the [[European Economic Community]] (EEC). However, due to objections over the supranational power of the Authority, their Councils had more powers; the new executive bodies were known as "Commissions".<ref name="ENA history">{{cite web|publisher = [[European NAvigator]]|title = Council of the European Union|url=http://www.ena.lu?lang=2&doc=5604|access-date = 24 June 2007}}</ref> |

|||

In 1965, the Council was hit by the "empty chair crisis". Due to disagreements between [[French President]] [[Charles de Gaulle]] and the Commission's agriculture proposals, among other things, France boycotted all meetings of the Council. This halted the Council's work until the impasse was resolved the following year by the [[Luxembourg compromise]]. Although initiated by a gamble of the President of the Commission, [[Walter Hallstein]], who later on lost the Presidency, the crisis exposed flaws in the Council's workings.<ref name="LSE Chair">{{cite web|last=Ludlow|first=N|year=2006|publisher=[[London School of Economics]]|title = De-commissioning the Empty Chair Crisis : the Community institutions and the crisis of 1965–6|url=http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2422/01/Decommisioningempty.pdf|access-date = 24 September 2007|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20071025203706/http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2422/01/Decommisioningempty.pdf |archive-date = 25 October 2007|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

Under the [[Merger Treaty]] of 1967, the ECSC's Special Council of Ministers and the Council of the EAEC (together with their other independent institutions) were merged into the '''Council of the European Communities''', which would act as a single Council for all three institutions.<ref>EUR-Lex, [https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=LEGISSUM:4301863 Treaty of Brussels (Merger Treaty)], updated 21 March 2018, accessed 29 January 2021</ref> In 1993, the Council adopted the name 'Council of the European Union', following the establishment of the European Union by the [[Maastricht Treaty]]. That treaty strengthened the Council, with the addition of more intergovernmental elements in the [[Three pillars of the European Union|three pillars]] system. However, at the same time the Parliament and Commission had been strengthened inside the [[European Community|Community pillar]], curtailing the ability of the Council to act independently.<ref name="ENA history"/> |

|||

The [[Treaty of Lisbon]] abolished the pillar system and gave further powers to Parliament. It also merged the Council's [[High Representative]] with the [[European Commissioner for External Relations|Commission's foreign policy head]], with this new figure chairing the foreign affairs Council rather than the rotating presidency. The [[European Council]] was declared a separate institution from the Council, also chaired by a permanent president, and the different Council configurations were mentioned in the treaties for the first time.<ref name="Const Info"/> |

|||

The development of the Council has been characterised by the rise in power of the Parliament, with which the Council has had to share its legislative powers. The Parliament has often provided opposition to the Council's wishes. This has in some cases led to clashes between both bodies with the Council's system of intergovernmentalism contradicting the developing parliamentary system and supranational principles.<ref name="Hoskyns">{{cite book| last = Hoskyns | first = Catherine |author2=Michael Newman | title = Democratizing the European Union: Issues for the twenty-first Century (Perspectives on Democratization | publisher = [[Manchester University Press]] | year = 2000 | isbn = 978-0-7190-5666-6 }}</ref> |

|||

== Овлашћења и функције == |

|||

The primary purpose of the Council is to act as one of two vetoing bodies of the [[Legislature of the European Union|EU's legislative branch]], the other being the [[European Parliament]]. Together they serve to amend, approve or disapprove the proposals of the [[European Commission]], which has the sole power to propose laws.<ref name="auto1"/><ref name="auto"/> Jointly with the Parliament, the Council holds the budgetary power of the Union and has greater control than the Parliament over the more intergovernmental areas of the EU, such as foreign policy and macroeconomic co-ordination. Finally, before the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, it formally held the executive power of the EU which it conferred upon the [[European Commission]].<ref name="Legislative power">{{cite web|publisher = [[Europa (web portal)|European Parliament]]|title=Legislative power|url = http://www.europarl.europa.eu/parliament/public/staticDisplay.do?id=46&pageRank=2&language=EN|access-date = 11 July 2007}}</ref><ref name="Treaty">{{cite web|publisher=[[Europa (web portal)]]|title=Treaty on the European Union (Nice consolidated version)|url=http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/oj/2006/ce321/ce32120061229en00010331.pdf|access-date=24 June 2007|archive-date=1 December 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071201005900/http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/oj/2006/ce321/ce32120061229en00010331.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> It is considered by some to be equivalent to an [[upper house]] of the EU legislature, although it's not described as such in the treaties.<ref>{{cite book |last1=A. Börzel |first1=Tanja |last2=A. Cichowski |first2=Rachel |title=The State of the European Union, 6:Law, politics, and society |date=4 September 2003 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0199257409 |page=147 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Bicameralism |date=13 June 1997 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9780521589727 |page=58 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Taub |first1=Amanda |title=The E.U. Is Democratic. It Just Doesn't Feel That Way. |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/30/world/europe/the-eu-is-democratic-it-just-doesnt-feel-that-way.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220101/https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/30/world/europe/the-eu-is-democratic-it-just-doesnt-feel-that-way.html |archive-date=2022-01-01 |url-access=limited |website=The New York Times |access-date=30 January 2020 |date=29 June 2016}}{{cbignore}}</ref> The Council represents the [[executive (government)|executive governments]] of the [[Member state of the European Union|EU's member states]]<ref name="eur-lex.europa.eu" /><ref name="Legislative power"/> and is based in the [[Europa building]] in Brussels.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/12/07-europa-building/|title=EUROPA : Home of the European Council and the Council of the EU - Consilium|website=www.consilium.europa.eu|language=en|access-date=7 May 2017}}</ref> |

|||

== Референце == |

|||

{{Reflist|}} |

|||

== Литература == |

|||

{{Refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* Anderson, P. ''The New Old World'' (Verso 2009) {{ISBN|978-1-84467-312-4}} |

|||

* [[Berend, Ivan T.]] ''The History of European Integration: A New Perspective''. (Routledge, 2016). |

|||

* Blair, Alasdair. ''The European Union since 1945'' (Routledge, 2014). |

|||

* Chaban, N. and M. Holland, eds. ''Communicating Europe in Times of Crisis: External Perceptions of the European Union'' (2014). |

|||

* Dedman, Martin. ''The origins and development of the European Union 1945-1995: a history of European integration'' (Routledge, 2006). |

|||

* [[Catherine E. de Vries|De Vries, Catherine E.]] "Don't Mention the War! Second World War Remembrance and Support for European Cooperation." ''JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies'' (2019). |

|||

* Dinan, Desmond. ''Europe recast: a history of European Union'' (2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan), 2004 [https://www.rienner.com/uploads/53aae65db9769.pdf excerpt]. |

|||

* Fimister, Alan. ''Robert Schuman: Neo-Scholastic Humanism and the Reunification of Europe'' (2008) |

|||

* Heuser, Beatrice. ''Brexit in History: Sovereignty or a European Union? '' (2019) [https://www.amazon.com/Brexit-History-Sovereignty-European-Union/dp/1787381269/ excerpt] also see [https://www.wsj.com/articles/brexit-in-history-review-lets-not-get-together-11580428449 online review] |

|||

* [[Sara Hobolt|Hobolt, Sara B.]] "The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent." ''Journal of European Public Policy'' (2016): 1–19. |

|||

* Jorgensen, Knud Erik, et al., eds. ''The SAGE Handbook of European Foreign Policy'' (Sage, 2015). |

|||

* [[Kaiser, Wolfram]]. "From state to society? The historiography of European integration." in Michelle Cini, and Angela K. Bourne, eds. ''Palgrave Advances in European Union Studies'' (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2006). pp 190–208. |

|||

* Kaiser, Wolfram, and Antonio Varsori, eds. ''European Union history: themes and debates'' (Springer, 2016). |

|||

* Koops, TJ. and G. Macaj. ''The European Union as a Diplomatic Actor'' (2015). |

|||

* [[John McCormick (political scientist)|McCormick, John]]. ''Understanding the European Union: a concise introduction'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). |

|||

* May, Alex. ''Britain and Europe since 1945'' (1999). |

|||

* Marsh, Steve, and Hans Mackenstein. ''The International Relations of the EU'' (Routledge, 2014). |

|||

* [[Milward, Alan S.]] ''The Reconstruction of Western Europe: 1945–51'' (Univ. of California Press, 1984) |

|||

*{{cite book|last1=Pasture|first1=Patrick|title=Imagining European unity since 1000 AD|date=2015|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|location=New York|isbn=9781137480460}} |

|||

* Patel, Kiran Klaus, and Wolfram Kaiser. "Continuity and change in European cooperation during the twentieth century." ''Contemporary European History'' 27.2 (2018): 165–182. [https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/E478ABB55246FBA32276D13F27818903/S096077731800005Xa.pdf/continuity_and_change_in_european_cooperation_during_the_twentieth_century.pdf online] |

|||

*{{cite book|editor1-last=Smith|editor1-first=M.L.|editor2-last=Stirk|editor2-first=P.M.R.|title=Making The New Europe: European Unity and the Second World War|date=1990|publisher=Pinter Publishers|location=London|isbn=0-86187-777-2|edition=1st UK}} |

|||

*{{cite book|editor1-last=Stirk|editor1-first=P.M.R.|title=European Unity in Context: The Interwar Period|date=1989|publisher=Pinter Publishers|location=London|isbn=9780861879878|edition=1st}} |

|||

* Young, John W. ''Britain, France, and the unity of Europe, 1945–1951'' (Leicester University, 1984). |

|||

*{{cite book|author1 = Craig, P.|author2 = de Búrca, G.|year = 2003|title = EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials|edition = 3rd|publisher = Oxford University Press|location = Oxford, New York|isbn = 0-19-925608-X|url-access = registration|url = https://archive.org/details/eulaw00paul}} |

|||

*{{cite journal|last=Voermans|first=Wim|year=2010|title=Is the European Legislator after Lisbon a real Legislature?|url=https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/15068|journal=Legislacao|volume=50|issue=50|pages=391–413}} |

|||

* [http://law.leiden.edu/organisation/publiclaw/europainstitute/staff/tobler.html Tobler, Christa]; Beglinger, Jacques (2018), ''Essential EU Law in Charts'' (4th ed.), Budapest: HVG-ORAC / E.M.Meijers Institute of Legal Studies, Leiden University. {{ISBN|978-963-258-394-5}}. See Chapter 5 (in particular [http://www.eur-charts.eu/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Samples_Essential-EU-Law-in-Charts_Tobler-Beglinger_2Ed-2010.pdf Chart 5|5 = p.3]), [http://www.eur-charts.eu www.eur-charts.eu]. |

|||

* {{citation | last1 = Corbett | first1 = Richard | last2 = Jacobs | first2 = Francis | last3 = Shackleton | first3 = Michael | title = The European Parliament | edition = 8 | url = http://www.johnharperpublishing.co.uk/pp007.shtml | publisher = John Harper Publishing |year=2011 | location = London | isbn = 978-0-9564508-5-2}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

|||

== Спољашње везе == |

== Спољашње везе == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Commonscat|Council of the European Union}} |

{{Commonscat|Council of the European Union}} |

||

* [http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ Official Council website] – [[Europa (web portal)|Europa]] |

|||

** [http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/council-eu/ About the Council] |

|||

** [http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/council-eu/configurations/ Council configurations] |

|||

** [http://video.consilium.europa.eu/ Live broadcast] |

|||

** [https://web.archive.org/web/20110719061623/http://prado.consilium.europa.eu/en/homeIndex.html PRADO – The Council of the European Union Public Register of Authentic Travel and ID Documents Online] |

|||

* [https://eur-lex.europa.eu/browse/institutions/council.html Access to documents of the EU Council] on [[EUR-Lex]] |

|||

* [http://www.ena.lu?lang=2&doc=23843 Council of the European Union] – [[European NAvigator]] |

|||

* [http://archives.eui.eu/en/fonds/ Archival material] concerning the Council of the European Union can be consulted at the [http://www.eui.eu/Research/HistoricalArchivesOfEU/Index.aspx Historical Archives of the European Union] in Florence |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Теме Европске уније}} |

{{Теме Европске уније}} |

||

Верзија на датум 17. јануар 2023. у 12:10

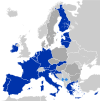

| Савет Европске уније | |

|---|---|

Сала у згради Европа у Бриселу којој се одржавају састанци Савета министара Европске уније од 2017. године | |

Амблем Савета Европске уније | |

| Датум оснивања | 1992. |

| Седиште | Брисел, |

| Чланови | 27 министара |

| Службени језици | енглески, француски, италијански |

| Генерални секретар | Thérèse Blanchet (од 1. новембра 2022) |

| Председавајућа држава | (од 1. јануара 2023) |

| Веб-сајт | www |

| Европска унија |

Ова чланак је део серије о |

Политике и питања

|

Савет Европске уније или Савет министара Европске уније је главни орган за доношење одлука у Европској унији. Оличење је земаља чланица, чије представнике окупља регуларно на министарском нивоу. На основу дневног реда, Савет се састаје у различитом саставу: инострани послови, финансије, образовање, телекомуникације итд.[1] То је једно од два законодавна тела и заједно са Европским парламентом служи за измену и одобравање или улагање вета на предлоге Европске комисије, која има право иницијативе.[2][3][4]

Савет има известан број обавеза:

- Он је законодавни орган Уније; за широк домен питања, практикује ту законодавну моћ заједно са Европским парламентом;

- Координира економским смеровима земаља чланица;

- Закључује, у име ЕУ, међународне договоре са једном или више држава или међународних организација;

- Заједно са Парламентом, руководи буџетом;

- Доноси одлуке потребне за утврђивање и спровођење заједничке међународне и безбедносне политике, на основу општих регулација које је донео Савет Европе;

- Координира активностима земаља чланица и усваја мерила у полицијској и правосудној сарадњи у питањима криминала

Седиште Савета је у Бриселу. Савет Европске уније не треба мешати са Европским саветом, засебним органом Европске уније, нити са Саветом Европе, засебном пан-европском институцијом са седиштем у Стразбуру, независном од ЕУ.

Председништво Савета Европске уније

| Председништво у Европском савету и у Савету Европске уније | |||||

| година, земља (1. половина, 2. половина) | |||||

| 2007. | Немачка, Португал | 2008. | Словенија, Француска | 2009. | Чешка, Шведска |

| 2010. | Шпанија, Белгија | 2011. | Мађарска, Пољска | 2012. | Данска, Кипар |

| 2013. | Ирска, Литванија | 2014. | Грчка, Италија | 2015. | Летонија, Луксембург |

| 2016. | Холандија, Словачка | 2017. | Малта, Естонија | 2018. | Бугарска, Аустрија |

| 2019. | Румунија, Финска | 2020. | Хрватска, Немачка | 2021. | Португалија, Словенија |

Састав

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

The Presidency of the Council rotates every six months among the governments of EU member states, with the relevant ministers of the respective country holding the Presidency at any given time ensuring the smooth running of the meetings and setting the daily agenda.[5] The continuity between presidencies is provided by an arrangement under which three successive presidencies, known as Presidency trios, share common political programmes. The Foreign Affairs Council (national foreign ministers) is however chaired by the Union's High Representative.[6]

Its decisions are made by qualified majority voting in most areas, unanimity in others, or just simple majority for procedural issues. Usually where it operates unanimously, it only needs to consult the Parliament. However, in most areas the ordinary legislative procedure applies meaning both Council and Parliament share legislative and budgetary powers equally, meaning both have to agree for a proposal to pass. In a few limited areas the Council may initiate new EU law itself.[5]

Историја

The Council first appeared in the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) as the "Special Council of Ministers", set up to counterbalance the High Authority (the supranational executive, now the Commission). The original Council had limited powers: issues relating only to coal and steel were in the Authority's domain, and the Council's consent was only required on decisions outside coal and steel. As a whole, the Council only scrutinised the High Authority (the executive). In 1957, the Treaties of Rome established two new communities, and with them two new Councils: the Council of the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC) and the Council of the European Economic Community (EEC). However, due to objections over the supranational power of the Authority, their Councils had more powers; the new executive bodies were known as "Commissions".[7]

In 1965, the Council was hit by the "empty chair crisis". Due to disagreements between French President Charles de Gaulle and the Commission's agriculture proposals, among other things, France boycotted all meetings of the Council. This halted the Council's work until the impasse was resolved the following year by the Luxembourg compromise. Although initiated by a gamble of the President of the Commission, Walter Hallstein, who later on lost the Presidency, the crisis exposed flaws in the Council's workings.[8]

Under the Merger Treaty of 1967, the ECSC's Special Council of Ministers and the Council of the EAEC (together with their other independent institutions) were merged into the Council of the European Communities, which would act as a single Council for all three institutions.[9] In 1993, the Council adopted the name 'Council of the European Union', following the establishment of the European Union by the Maastricht Treaty. That treaty strengthened the Council, with the addition of more intergovernmental elements in the three pillars system. However, at the same time the Parliament and Commission had been strengthened inside the Community pillar, curtailing the ability of the Council to act independently.[7]

The Treaty of Lisbon abolished the pillar system and gave further powers to Parliament. It also merged the Council's High Representative with the Commission's foreign policy head, with this new figure chairing the foreign affairs Council rather than the rotating presidency. The European Council was declared a separate institution from the Council, also chaired by a permanent president, and the different Council configurations were mentioned in the treaties for the first time.[6]

The development of the Council has been characterised by the rise in power of the Parliament, with which the Council has had to share its legislative powers. The Parliament has often provided opposition to the Council's wishes. This has in some cases led to clashes between both bodies with the Council's system of intergovernmentalism contradicting the developing parliamentary system and supranational principles.[10]

Овлашћења и функције

The primary purpose of the Council is to act as one of two vetoing bodies of the EU's legislative branch, the other being the European Parliament. Together they serve to amend, approve or disapprove the proposals of the European Commission, which has the sole power to propose laws.[2][4] Jointly with the Parliament, the Council holds the budgetary power of the Union and has greater control than the Parliament over the more intergovernmental areas of the EU, such as foreign policy and macroeconomic co-ordination. Finally, before the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, it formally held the executive power of the EU which it conferred upon the European Commission.[11][12] It is considered by some to be equivalent to an upper house of the EU legislature, although it's not described as such in the treaties.[13][14][15] The Council represents the executive governments of the EU's member states[1][11] and is based in the Europa building in Brussels.[16]

Референце

- ^ а б „EUR-Lex - C:2016:202:TOC - EN - EUR-Lex”. eur-lex.europa.eu.

- ^ а б „Legislative powers”. European Parliament. Приступљено 13. 2. 2019.

- ^ „Parliament's legislative initiative” (PDF). Library of the European Parliament. 24. 10. 2013. Архивирано (PDF) из оригинала 19. 3. 2014. г. Приступљено 13. 2. 2019.

- ^ а б „Planning and proposing law”. European Commission. 20. 4. 2019.

- ^ а б „Council of the European Union”. Council of the European Union. 16. 6. 2016. Приступљено 19. 2. 2017.

- ^ а б „The Union's institutions: The Council of Ministers”. Europa (web portal). Приступљено 1. 7. 2007.

- ^ а б „Council of the European Union”. European NAvigator. Приступљено 24. 6. 2007.

- ^ Ludlow, N (2006). „De-commissioning the Empty Chair Crisis : the Community institutions and the crisis of 1965–6” (PDF). London School of Economics. Архивирано из оригинала (PDF) 25. 10. 2007. г. Приступљено 24. 9. 2007.

- ^ EUR-Lex, Treaty of Brussels (Merger Treaty), updated 21 March 2018, accessed 29 January 2021

- ^ Hoskyns, Catherine; Michael Newman (2000). Democratizing the European Union: Issues for the twenty-first Century (Perspectives on Democratization. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5666-6.

- ^ а б „Legislative power”. European Parliament. Приступљено 11. 7. 2007.

- ^ „Treaty on the European Union (Nice consolidated version)” (PDF). Europa (web portal). Архивирано из оригинала (PDF) 1. 12. 2007. г. Приступљено 24. 6. 2007.

- ^ A. Börzel, Tanja; A. Cichowski, Rachel (4. 9. 2003). The State of the European Union, 6:Law, politics, and society. Oxford University Press. стр. 147. ISBN 978-0199257409.

- ^ Bicameralism. Cambridge University Press. 13. 6. 1997. стр. 58. ISBN 9780521589727.

- ^ Taub, Amanda (29. 6. 2016). „The E.U. Is Democratic. It Just Doesn't Feel That Way.”. The New York Times. Архивирано из оригинала

2022-01-01. г. Приступљено 30. 1. 2020.

2022-01-01. г. Приступљено 30. 1. 2020.

- ^ „EUROPA : Home of the European Council and the Council of the EU - Consilium”. www.consilium.europa.eu (на језику: енглески). Приступљено 7. 5. 2017.

Литература

- Anderson, P. The New Old World (Verso 2009) ISBN 978-1-84467-312-4

- Berend, Ivan T. The History of European Integration: A New Perspective. (Routledge, 2016).

- Blair, Alasdair. The European Union since 1945 (Routledge, 2014).

- Chaban, N. and M. Holland, eds. Communicating Europe in Times of Crisis: External Perceptions of the European Union (2014).

- Dedman, Martin. The origins and development of the European Union 1945-1995: a history of European integration (Routledge, 2006).

- De Vries, Catherine E. "Don't Mention the War! Second World War Remembrance and Support for European Cooperation." JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies (2019).

- Dinan, Desmond. Europe recast: a history of European Union (2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan), 2004 excerpt.

- Fimister, Alan. Robert Schuman: Neo-Scholastic Humanism and the Reunification of Europe (2008)

- Heuser, Beatrice. Brexit in History: Sovereignty or a European Union? (2019) excerpt also see online review

- Hobolt, Sara B. "The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent." Journal of European Public Policy (2016): 1–19.

- Jorgensen, Knud Erik, et al., eds. The SAGE Handbook of European Foreign Policy (Sage, 2015).

- Kaiser, Wolfram. "From state to society? The historiography of European integration." in Michelle Cini, and Angela K. Bourne, eds. Palgrave Advances in European Union Studies (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2006). pp 190–208.

- Kaiser, Wolfram, and Antonio Varsori, eds. European Union history: themes and debates (Springer, 2016).

- Koops, TJ. and G. Macaj. The European Union as a Diplomatic Actor (2015).

- McCormick, John. Understanding the European Union: a concise introduction (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

- May, Alex. Britain and Europe since 1945 (1999).

- Marsh, Steve, and Hans Mackenstein. The International Relations of the EU (Routledge, 2014).

- Milward, Alan S. The Reconstruction of Western Europe: 1945–51 (Univ. of California Press, 1984)

- Pasture, Patrick (2015). Imagining European unity since 1000 AD. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137480460.

- Patel, Kiran Klaus, and Wolfram Kaiser. "Continuity and change in European cooperation during the twentieth century." Contemporary European History 27.2 (2018): 165–182. online

- Smith, M.L.; Stirk, P.M.R., ур. (1990). Making The New Europe: European Unity and the Second World War (1st UK изд.). London: Pinter Publishers. ISBN 0-86187-777-2.

- Stirk, P.M.R., ур. (1989). European Unity in Context: The Interwar Period (1st изд.). London: Pinter Publishers. ISBN 9780861879878.

- Young, John W. Britain, France, and the unity of Europe, 1945–1951 (Leicester University, 1984).

- Craig, P.; de Búrca, G. (2003). EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials

(3rd изд.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925608-X.

(3rd изд.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925608-X. - Voermans, Wim (2010). „Is the European Legislator after Lisbon a real Legislature?”. Legislacao. 50 (50): 391—413.

- Tobler, Christa; Beglinger, Jacques (2018), Essential EU Law in Charts (4th ed.), Budapest: HVG-ORAC / E.M.Meijers Institute of Legal Studies, Leiden University. ISBN 978-963-258-394-5. See Chapter 5 (in particular Chart 5|5 = p.3), www.eur-charts.eu.

- Corbett, Richard; Jacobs, Francis; Shackleton, Michael (2011), The European Parliament (8 изд.), London: John Harper Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9564508-5-2

Спољашње везе

- Official Council website – Europa

- Access to documents of the EU Council on EUR-Lex

- Council of the European Union – European NAvigator

- Archival material concerning the Council of the European Union can be consulted at the Historical Archives of the European Union in Florence