Инфективна болест — разлика између измена

м Бот: по захтеву Вукса |

. ознака: везе до вишезначних одредница |

||

| Ред 1: | Ред 1: | ||

{{Short description|Инвазија патогених агенаса на тело организма}} |

|||

[[Датотека:Malaria.jpg|десно|безоквира]] |

|||

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

|||

'''Инфективне болести''' су врста [[Болест|обољења]] људи и животиња изазваних спољним биолошким изазивачем; [[Mikroorganizam|микроорганизмом]] ([[бактерија]], [[паразит]], [[гљиве|гљивица]], [[вирус]]), или [[Протеин|беланчевином]] ([[приони|прион]]).<ref name="MandelInfectiousDiseases">{{Mandell_InfectiousDiseases5th}}</ref><ref>[http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/infection Definition of "infection" from several medical dictionaries] – Приступљено 2012-04-03</ref><ref name="News Ghana">{{cite news|url=http://newsghana.com.gh/?p=853675 | title=Utilizing antibiotics agents effectively will preserve present day medication| publisher=News Ghana |date=21. 11. 2015 | accessdate=21. 11. 2015}}</ref> [[Инфекција]] сама по себи није болест, јер она само понекад доводи до обољења. Инфективне болести исказују широки спектар могућих [[симптом]]а и клиничких слика развоја болести. Симптоми се могу јавити у року од неколико дана, недеља, или чак година од заразе. Зависно од личног [[Имунски систем|имунитета]]<ref name="KubyImmunology6th">{{KubyImmunology6th}}</ref> и врсте инфекције, инфективне болести могу да изазову само незнатне симптоме и прођу без посебног лечења. Неке инфекције брзо изазивају драматичне здравствене сметње. У случају [[Сепса|сепсе]], организам реагује одбрамбеном реакцијом која изазива [[Грозница|грозницу]], убрзани пулс и ритам дисања, жеђ и умор. За прогнозу инфективне болести одлучујућа је способност имунског система да елиминише узрочника болести. Медицинска наука је развила ефикасне методе за борбу против многих инфективних болести ([[антибиотик]]е за елиминисање бактерија, [[антимикотик]]е за борбу против гљивица и [[виростатик]]е против вируса). Против неких болести развијене су [[Вакцина|вакцине]]. За један број инфективних болести ни данас не постоји ефикасан лек. |

|||

| name = Инфекција |

|||

| image = Malaria.jpg |

|||

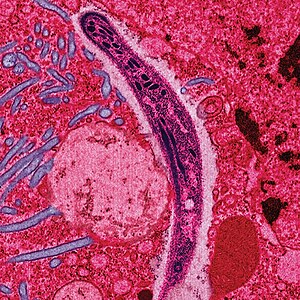

| caption = False-colored [[electron micrograph]] showing a [[malaria]] [[sporozoite]] migrating through the [[midgut]] [[epithelium]] of a [[rat]] |

|||

| field = [[Infectious diseases (medical specialty)|Infectious diseases]] |

|||

| symptoms = |

|||

| complications = |

|||

| onset = |

|||

| duration = |

|||

| types = |

|||

| causes = [[pathogenic bacteria|bacterial]], [[viral disease|viral]], [[parasitic disease|parasitic]], [[mycosis|fungal]], [[prion]] |

|||

| risks = |

|||

| diagnosis = |

|||

| differential = |

|||

| prevention = |

|||

| treatment = |

|||

| medication = |

|||

| prognosis = |

|||

| frequency = |

|||

| deaths = |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Инфективне болести''' су врста [[Болест|обољења]] људи и животиња изазваних спољним биолошким изазивачем; [[Mikroorganizam|микроорганизмом]] ([[бактерија]], [[паразит]], [[гљиве|гљивица]], [[вирус]]), или [[Протеин|беланчевином]] ([[приони|прион]]).<ref name="MandelInfectiousDiseases">{{Mandell_InfectiousDiseases5th}}</ref><ref>[http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/infection Definition of "infection" from several medical dictionaries] – Приступљено 2012-04-03</ref><ref name="News Ghana">{{cite news|url=http://newsghana.com.gh/?p=853675 | title=Utilizing antibiotics agents effectively will preserve present day medication| publisher=News Ghana |date=21. 11. 2015 | accessdate=21. 11. 2015}}</ref> [[Инфекција]] сама по себи није болест, јер она само понекад доводи до обољења. Инфективне болести исказују широки спектар могућих [[Симптоми болести|симптом]]а и клиничких слика развоја болести. Симптоми се могу јавити у року од неколико дана, недеља, или чак година од заразе. Зависно од личног [[Имунски систем|имунитета]]<ref name="KubyImmunology6th">{{KubyImmunology6th}}</ref> и врсте инфекције, инфективне болести могу да изазову само незнатне симптоме и прођу без посебног лечења. Неке инфекције брзо изазивају драматичне здравствене сметње. У случају [[Сепса|сепсе]], организам реагује одбрамбеном реакцијом која изазива [[Грозница|грозницу]], убрзани пулс и ритам дисања, жеђ и умор. За прогнозу инфективне болести одлучујућа је способност имунског система да елиминише узрочника болести. Медицинска наука је развила ефикасне методе за борбу против многих инфективних болести ([[антибиотик]]е за елиминисање бактерија, [[антимикотик]]е за борбу против гљивица и [[виростатик]]е против вируса). Против неких болести развијене су [[Вакцина|вакцине]]. За један број инфективних болести ни данас не постоји ефикасан лек. Проучавањем инфективних болести бави се [[инфектологија]], а механизмима одбране огранизма бави се [[имунологија]].<ref name="MandelInfectiousDiseases"/> |

|||

{{рут}} |

|||

Infections can be caused by a wide range of [[pathogen]]s, most prominently [[pathogenic bacteria|bacteria]] and [[virus]]es.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Sehgal|first1=Mukul|last2=Ladd|first2=Hugh J.|last3=Totapally|first3=Balagangadhar|date=2020-12-01|title=Trends in Epidemiology and Microbiology of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock in Children|url=https://hosppeds.aappublications.org/content/10/12/1021|journal=Hospital Pediatrics|language=en|volume=10|issue=12|pages=1021–1030|doi=10.1542/hpeds.2020-0174|issn=2154-1663|pmid=33208389|s2cid=227067133|doi-access=free|access-date=2021-03-26|archive-date=2021-04-13|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210413210453/https://hosppeds.aappublications.org/content/10/12/1021|url-status=live}}</ref> Hosts can fight infections using their [[immune system|immune systems]]. [[Mammal]]ian hosts react to infections with an [[Innate immune system|innate]] response, often involving [[inflammation]], followed by an [[Adaptive immune system|adaptive]] response. |

|||

Specific [[pharmaceutical drug|medications]] used to treat infections include [[antibiotic]]s, [[antiviral drug|antivirals]], [[antifungal medication|antifungals]], [[Antiprotozoal agent|antiprotozoals]],<ref>{{Cite web |title=Antiprotozoal Drugs |url=https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Antiprotozoal+Drugs |access-date=2022-04-22 |website=TheFreeDictionary.com |archive-date=2022-01-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220122142518/https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Antiprotozoal+Drugs |url-status=live }}</ref> and [[antihelminthic]]s. Infectious diseases resulted in 9.2 million deaths in 2013 (about 17% of all deaths).<ref name=GDB2013>{{cite journal|author=((GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators))|title=Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study |journal=Lancet|date=17 December 2014|pmid=25530442|doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2|volume=385|issue=9963|pages=117–71|pmc=4340604}}</ref> The branch of [[medicine]] that focuses on infections is referred to as [[infectious diseases (medical specialty)|infectious diseases]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.aamc.org/cim/specialty/list/us/339608/infectious_disease_-internal_medicine.html |title=Infectious Disease, Internal Medicine |publisher=Association of American Medical Colleges |access-date=2015-08-20 |quote=Infectious disease is the subspecialty of internal medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of communicable diseases of all types, in all organs, and in all ages of patients. |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150206201010/https://www.aamc.org/cim/specialty/list/us/339608/infectious_disease_-internal_medicine.html |archive-date=2015-02-06 }}</ref> |

|||

Проучавањем инфективних болести бави се [[инфектологија]], а механизмима одбране огранизма бави се [[имунологија]].<ref name="MandelInfectiousDiseases"/> |

|||

== Узроци == |

== Узроци == |

||

| Ред 24: | Ред 48: | ||

Само овај последњи тип се рачуна као заразна болест. |

Само овај последњи тип се рачуна као заразна болест. |

||

Infections are caused by infectious agents ([[pathogen]]s) including: |

|||

* [[Pathogenic bacteria|Bacteria]] (e.g. ''[[Mycobacterium tuberculosis]]'', ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'', ''[[Escherichia coli]]'', ''[[Clostridium botulinum]]'', and ''[[Salmonella]]'' spp.) |

|||

* [[Viral infection|Virus]]es and related agents such as [[viroid]]s. (E.g. ''[[HIV]]'', ''[[Rhinovirus]]'', ''[[Lyssavirus]]es'' such as ''[[Rabies virus]]'', ''[[Ebolavirus]]'' and ''[[Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2]]'') |

|||

* [[Fungal infection|Fungi]], further subclassified into: |

|||

** [[Ascomycota]], including yeasts such as [[Candida (fungus)|''Candida'']] (the most common [[fungal infection]]); filamentous fungi such as ''[[Aspergillus]];'' ''[[Pneumocystis]]'' species; and [[Dermatophytosis|dermatophytes]], a group of organisms causing infection of skin and other superficial structures in humans.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/index.html|title=Types of Fungal Diseases|date=2019-06-27|website=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|language=en-us|access-date=2019-12-09|archive-date=2020-04-01|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200401195307/https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/index.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

** [[Basidiomycota]], including the human-pathogenic genus ''[[Cryptococcus]].''<ref>{{Citation|last1=Mada|first1=Pradeep Kumar|title=Cryptococcus (Cryptococcosis)|date=2019|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/|work=StatPearls|publisher=StatPearls Publishing|pmid=28613714|access-date=2019-12-09|last2=Jamil|first2=Radia T.|last3=Alam|first3=Mohammed U.|archive-date=2020-06-19|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200619195643/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431060/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Parasitic disease|Parasite]]s, which are usually divided into:<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/about.html|title=About Parasites|date=2019-02-25|website=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|language=en-us|access-date=2019-12-09|archive-date=2019-12-25|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191225043311/https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/about.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

** Unicellular organisms (e.g. [[Plasmodium|malaria]], ''[[Toxoplasma gondii|Toxoplasma]]'', ''[[Babesia]]'') |

|||

** Macroparasites<ref>{{Cite journal |jstor = 656401|title = Microparasites and Macroparasites|journal = Cultural Anthropology|volume = 2|issue = 1|pages = 155–71|last1 = Brown|first1 = Peter J.|year = 1987|doi = 10.1525/can.1987.2.1.02a00120}}</ref> ([[Parasitic worm|worms or helminths]]) including [[nematode]]s such as [[parasitic]] [[roundworm]]s and [[pinworm (parasite)|pinworms]], [[tapeworm]]s (cestodes), and flukes ([[trematodes]], such as [[schistosomes]]). Diseases caused by [[Parasitic worm|helminths]] are sometimes termed infestations, but are sometimes called infections. |

|||

** [[Arthropod]]s such as [[tick]]s, [[mite]]s, [[flea]]s, and [[lice]], can also cause human disease, which conceptually are similar to infections, but invasion of a human or animal body by these macroparasites is usually termed [[infestation]]. |

|||

* [[Prion]]s (although they do not secrete toxins) |

|||

== Инфекције према узроку == |

== Инфекције према узроку == |

||

Бактеријске и вирусне инфекције могу узроковати сличне симптоме у које се могу убројати осећај слабости, повишена телесна температура и дрхтање. Понекад је медицинском особљу тешко да утврдити узрок дате инфекције. Веома је важно да се уочи разлика између инфекција према њиховом узроку како би се одредио адекватан третман и [[терапија]]. Вирусне инфекције се не могу излечити применом [[антибиотик]]а. |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

{|class="wikitable" |

||

| Ред 42: | Ред 78: | ||

| Узрок || Патогени вируси || Патогене бактерије |

| Узрок || Патогени вируси || Патогене бактерије |

||

|} |

|} |

||

==Signs and symptoms== |

|||

The [[signs and symptoms]] of an infection depend on the type of disease. Some signs of infection affect the whole body generally, such as [[fatigue]], loss of appetite, weight loss, [[fever]]s, night sweats, chills, aches and pains. Others are specific to individual body parts, such as skin [[rash]]es, [[cough]]ing, or a [[Rhinorrhea|runny nose]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Runny Nose: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment |url=https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/17660-runny-nose |access-date=2022-04-22 |website=Cleveland Clinic |archive-date=2022-05-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220510130201/https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/17660-runny-nose |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

In certain cases, infectious diseases may be [[asymptomatic]] for much or even all of their course in a given host. In the latter case, the disease may only be defined as a "disease" (which by definition means an illness) in hosts who secondarily become ill after contact with an [[asymptomatic carrier]]. An infection is not synonymous with an infectious disease, as some infections do not cause illness in a host.<ref name=Sherris>{{cite book |veditors=Ryan KJ, Ray CG | title = Sherris Medical Microbiology | edition = 4th | publisher = McGraw Hill | year = 2004 | isbn = 978-0-8385-8529-0 }}</ref> |

|||

===Bacterial or viral=== |

|||

As bacterial and viral infections can both cause the same kinds of symptoms, it can be difficult to distinguish which is the cause of a specific infection.<ref name="nipa">{{Cite web |title=NIPA - Bacteria - Bacterial vs. Viral infections |url=http://www.antibiotics-info.org/bact02.html |access-date=2023-11-10 |website=www.antibiotics-info.org |archive-date=2023-11-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231110111321/http://www.antibiotics-info.org/bact02.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Distinguishing the two is important, since viral infections cannot be cured by [[antibiotic]]s whereas bacterial infections can.<ref>{{cite book| title =The Truth About Illness and Disease|author1=Robert N. Golden |author2=Fred Peterson |publisher= Infobase Publishing|page=181|isbn= 978-1438126371|year=2009 }}</ref> |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

|+Comparison of viral and bacterial infection |

|||

|- |

|||

! Characteristic |

|||

! [[Viral disease|Viral infection]] |

|||

! [[Pathogenic bacteria|Bacterial infection]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|| Typical symptoms |

|||

| In general, viral infections are systemic. This means they involve many different parts of the body or more than one body system at the same time; i.e. a runny nose, sinus congestion, cough, body aches etc. They can be local at times as in viral [[conjunctivitis]] or "pink eye" and herpes. Only a few viral infections are painful, like [[Herpes simplex virus|herpes]]. The pain of viral infections is often described as itchy or burning.<ref name="nipa"/> |

|||

| The classic symptoms of a bacterial infection are localized redness, heat, swelling and pain. One of the hallmarks of a bacterial infection is local pain, pain that is in a specific part of the body. For example, if a cut occurs and is infected with bacteria, pain occurs at the site of the infection. Bacterial throat pain is often characterized by more pain on one side of the throat. An [[ear infection]] is more likely to be diagnosed as bacterial if the pain occurs in only one ear.<ref name=nipa/> A cut that produces pus and milky-colored liquid is most likely infected.<ref>{{cite web|publisher=Rencare |url=http://www.rencareltd.com/conditions/infections/ |title=Infection |access-date=4 July 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120305023556/http://www.rencareltd.com/conditions/infections/ |archive-date=March 5, 2012 }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| Cause || [[Pathogenic viruses]] || [[Pathogenic bacteria]] |

|||

|} |

|||

==Pathophysiology== |

|||

[[File:Chain of Infection.png|thumb|Chain of infection; the chain of events that lead to infection]] |

|||

There is a general chain of events that applies to infections, sometimes called the '''chain of infection'''<ref>{{Cite web |title=Infection Cycle Symptoms and Treatment |url=https://infectioncycle.com/ |access-date=2023-11-10 |website=Infection Cycle |language=en-US |archive-date=2023-11-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231110111321/https://infectioncycle.com/ |url-status=live }}</ref> or '''transmission chain'''. The chain of events involves several steps{{snd}}which include the infectious agent, reservoir, entering a susceptible host, exit and transmission to new hosts. Each of the links must be present in a chronological order for an infection to develop. Understanding these steps helps health care workers target the infection and prevent it from occurring in the first place.<ref>{{Citation |author1=((National Institutes of Health (US)))|title=Understanding Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases |date=2007 |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20370/ |work=NIH Curriculum Supplement Series [Internet] |access-date=2023-11-17 |publisher=National Institutes of Health (US) |language=en |last2=Study |first2=Biological Sciences Curriculum |archive-date=2023-06-26 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230626004621/https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20370/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

===Colonization=== |

|||

[[File:Dit del peu gros infectat.jpg|thumb|Infection of an [[ingrown nail|ingrown toenail]]; there is pus (yellow) and resultant inflammation (redness and swelling around the nail).]] |

|||

Infection begins when an organism successfully enters the body, grows and multiplies. This is referred to as colonization. Most humans are not easily infected. Those with compromised or weakened immune systems have an increased susceptibility to chronic or persistent infections. Individuals who have a suppressed [[immune system]] are particularly susceptible to [[opportunistic infection]]s. Entrance to the host at [[host–pathogen interface]], generally occurs through the [[Mucous membrane|mucosa]] in orifices like the [[oral cavity]], nose, eyes, genitalia, anus, or the microbe can enter through open wounds. While a few organisms can grow at the initial site of entry, many migrate and cause systemic infection in different organs. Some pathogens grow within the host cells (intracellular) whereas others grow freely in bodily fluids.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Peterson |first=Johnny W. |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8526/ |title=Bacterial Pathogenesis |date=1996 |publisher=University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston |language=en |pmid=21413346 |isbn=9780963117212 |access-date=2022-10-20 |archive-date=2016-04-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160425080845/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8526/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

[[Wound]] colonization refers to non-replicating microorganisms within the wound, while in infected wounds, replicating organisms exist and tissue is injured.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Negut|first1=Irina|last2=Grumezescu|first2=Valentina|last3=Grumezescu|first3=Alexandru Mihai|date=2018-09-18|title=Treatment Strategies for Infected Wounds|journal=Molecules |volume=23|issue=9|doi=10.3390/molecules23092392|issn=1420-3049|pmc=6225154|pmid=30231567|page=2392|doi-access=free}}</ref> All [[multicellular organism]]s are colonized to some degree by extrinsic organisms, and the vast majority of these exist in either a [[Mutualism (biology)|mutualistic]] or [[commensal]] relationship with the host. An example of the former is the [[Anaerobic organism|anaerobic bacteria]] species, which colonizes the [[mammal]]ian [[colon (anatomy)|colon]], and an example of the latter are the various species of [[staphylococcus]] that exist on [[human skin]]. Neither of these colonizations are considered infections. The difference between an infection and a colonization is often only a matter of circumstance. Non-pathogenic organisms can become pathogenic given specific conditions, and even the most [[virulent]] organism requires certain circumstances to cause a compromising infection. Some colonizing bacteria, such as ''[[Corynebacteria]] sp.'' and ''[[Viridans streptococci]]'', prevent the adhesion and colonization of pathogenic bacteria and thus have a symbiotic relationship with the host, preventing infection and speeding [[wound healing]]. |

|||

[[File:Pathogenic Infection.png|thumb|This image depicts the steps of pathogenic infection.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Duerkop |first1=Breck A |last2=Hooper |first2=Lora V |date=2013-07-01 |title=Resident viruses and their interactions with the immune system |journal=Nature Immunology |language=en |volume=14 |issue=7 |pages=654–59 |doi=10.1038/ni.2614 |pmc=3760236 |pmid=23778792}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Bacterial Pathogenesis at Washington University |url=https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/bacterial-pathogenesis/deck/11094651 |access-date=2016-12-02 |website=StudyBlue |location=St. Louis |archive-date=2016-12-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161203060624/https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/bacterial-pathogenesis/deck/11094651 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Print Friendly |url=http://www.lifeextension.com/magazine/2014/6/the-dangers-of-using-antibiotics-to-prevent-urinary-tract-infections/page-01?p=1 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161202235200/http://www.lifeextension.com/magazine/2014/6/the-dangers-of-using-antibiotics-to-prevent-urinary-tract-infections/page-01?p=1 |archive-date=2016-12-02 |access-date=2016-12-02 |website=www.lifeextension.com}}</ref>]] |

|||

The variables involved in the outcome of a host becoming inoculated by a pathogen and the ultimate outcome include: |

|||

* the route of entry of the [[pathogen]] and the access to host regions that it gains |

|||

* the intrinsic [[virulence]] of the particular organism |

|||

* the quantity or load of the initial inoculant |

|||

* the [[immune system|immune]] status of the host being colonized |

|||

As an example, several [[staphylococcus|staphylococcal]] species remain harmless on the skin, but, when present in a normally [[sterile technique|sterile]] space, such as in the capsule of a [[joint]] or the [[peritoneum]], multiply without resistance and cause harm.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Tong |first1=Steven Y. C. |last2=Davis |first2=Joshua S. |last3=Eichenberger |first3=Emily |last4=Holland |first4=Thomas L. |last5=Fowler |first5=Vance G. |date=2015 |title=Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management |journal=Clinical Microbiology Reviews |volume=28 |issue=3 |pages=603–661 |doi=10.1128/CMR.00134-14 |issn=0893-8512 |pmc=4451395 |pmid=26016486}}</ref> |

|||

An interesting fact that [[gas chromatography–mass spectrometry]], [[16S ribosomal RNA]] analysis, [[omics]], and other advanced technologies have made more apparent to humans in recent decades is that microbial colonization is very common even in environments that humans think of as being nearly [[asepsis|sterile]]. Because it is normal to have bacterial colonization, it is difficult to know which chronic wounds can be classified as infected and how much risk of progression exists. Despite the huge number of wounds seen in clinical practice, there are limited quality data for evaluated symptoms and signs. A review of chronic wounds in the [[JAMA|Journal of the American Medical Association]]'s "Rational Clinical Examination Series" quantified the importance of increased pain as an indicator of infection.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Reddy M, Gill SS, Wu W | date = Feb 2012 | title = Does this patient have an infection of a chronic wound? | journal = JAMA | volume = 307 | issue = 6| pages = 605–11 | doi = 10.1001/jama.2012.98 | pmid = 22318282 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> The review showed that the most useful finding is an increase in the level of pain [likelihood ratio (LR) range, 11–20] makes infection much more likely, but the absence of pain (negative likelihood ratio range, 0.64–0.88) does not rule out infection (summary LR 0.64–0.88). |

|||

{{anchor|Persistent infection}} |

|||

===Disease=== |

|||

[[Disease]] can arise if the host's protective immune mechanisms are compromised and the organism inflicts damage on the host. [[Microorganism]]s can cause tissue damage by releasing a variety of toxins or destructive enzymes. For example, ''[[Clostridium tetani]]'' releases a toxin that paralyzes muscles, and [[staphylococcus]] releases toxins that produce shock and [[Sepsis|sepsis]]. Not all infectious agents cause disease in all hosts. For example, less than 5% of individuals infected with [[polio]] develop disease.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4215.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4215.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |title=Polio: Questions and Answers |website=immunize.org |access-date=9 July 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> On the other hand, some infectious agents are highly virulent. The [[prion]] causing [[Bovine spongiform encephalopathy|mad cow disease]] and [[Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease]] invariably kills all animals and people that are infected.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Trent |first=Ronald J |title=Infectious Diseases |date=2005 |journal=Molecular Medicine |pages=193–220 |doi=10.1016/B978-012699057-7/50008-4 |pmc=7149788|isbn=9780126990577 }}</ref> |

|||

Persistent infections occur because the body is unable to clear the organism after the initial infection. Persistent infections are characterized by the continual presence of the infectious organism, often as latent infection with occasional recurrent relapses of active infection. There are some viruses that can maintain a persistent infection by infecting different cells of the body. Some viruses once acquired never leave the body. A typical example is the herpes virus, which tends to hide in nerves and become reactivated when specific circumstances arise.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rouse |first1=Barry T. |last2=Sehrawat |first2=Sharvan |date=2010 |title=Immunity and immunopathology to viruses: what decides the outcome? |journal=Nature Reviews Immunology |language=en |volume=10 |issue=7 |pages=514–526 |doi=10.1038/nri2802 |pmid=20577268 |pmc=3899649 |issn=1474-1741}}</ref> |

|||

Persistent infections cause millions of deaths globally each year.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.persistentinfection.net/ |title=Chronic Infection Information |website=persistentinfection.net |access-date=2010-01-14 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150722065612/http://www.persistentinfection.net/ |archive-date=July 22, 2015}}</ref> Chronic infections by parasites account for a high morbidity and mortality in many underdeveloped countries.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Torgerson|first1=Paul R.|last2=Devleesschauwer|first2=Brecht|last3=Praet|first3=Nicolas|last4=Speybroeck|first4=Niko|last5=Willingham|first5=Arve Lee|last6=Kasuga|first6=Fumiko|last7=Rokni|first7=Mohammad B.|last8=Zhou|first8=Xiao-Nong|last9=Fèvre|first9=Eric M.|last10=Sripa|first10=Banchob|last11=Gargouri|first11=Neyla|date=2015-12-03|title=World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 11 Foodborne Parasitic Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis|journal=PLOS Medicine|volume=12|issue=12|pages=e1001920|doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001920|issn=1549-1277|pmc=4668834|pmid=26633705 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Citation|last1=Hotez|first1=Peter J.|title=Helminth Infections: Soil-transmitted Helminth Infections and Schistosomiasis|date=2006|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11748/|work=Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries|editor-last=Jamison|editor-first=Dean T.|edition=2nd|place=Washington (DC)|publisher=World Bank|isbn=978-0-8213-6179-5|pmid=21250326|access-date=2021-08-13|last2=Bundy|first2=Donald A. P.|last3=Beegle|first3=Kathleen|last4=Brooker|first4=Simon|last5=Drake|first5=Lesley|last6=de Silva|first6=Nilanthi|last7=Montresor|first7=Antonio|last8=Engels|first8=Dirk|last9=Jukes|first9=Matthew|editor2-last=Breman|editor2-first=Joel G.|editor3-last=Measham|editor3-first=Anthony R.|editor4-last=Alleyne|editor4-first=George|archive-date=2016-10-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161010040542/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11748/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

===Transmission<!--linked from 'Transmission (medicine)'-->=== |

|||

{{Main|Transmission (medicine)}} |

|||

[[File:CulexNil.jpg|thumb|220px|A southern house mosquito (''[[Culex quinquefasciatus]]'') is a [[disease vector|vector]] that transmits the pathogens that cause [[West Nile fever]] and [[avian malaria]] among others.]]For infecting organisms to survive and repeat the infection cycle in other hosts, they (or their progeny) must leave an existing reservoir and cause infection elsewhere. Infection transmission can take place via many potential routes:<ref>{{cite web | title = How Infections Spread | url = https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/spread/index.html | website = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | date = 1 January 2016 | access-date = 17 October 2021 | archive-date = 2 June 2023 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230602112416/https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/spread/index.html | url-status = live }}</ref> |

|||

* '''Droplet contact''', also known as the ''respiratory route'', and the resultant infection can be termed [[airborne disease]]. If an infected person coughs or sneezes on another person the microorganisms, suspended in warm, moist droplets, may enter the body through the nose, mouth or eye surfaces. |

|||

* '''Fecal-oral transmission''', wherein foodstuffs or water become contaminated (by people not washing their hands before preparing food, or untreated sewage being released into a drinking water supply) and the people who eat and drink them become infected. Common [[Fecal–oral route|fecal-oral]] transmitted pathogens include ''[[Vibrio cholerae]]'', ''[[Giardia]]'' species, [[rotavirus]]es, ''[[Entamoeba histolytica]]'', ''[[Escherichia coli]]'', and [[tape worm]]s.<ref>[http://www.fungusfocus.com/html/flukes.htm Intestinal Parasites and Infection] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101028013944/http://fungusfocus.com/html/flukes.htm |date=2010-10-28 }} fungusfocus.com – Retrieved on 2010-01-21</ref> Most of these pathogens cause [[gastroenteritis]]. |

|||

* '''Sexual transmission''', with the result being called [[sexually transmitted infection]]. |

|||

* '''Oral transmission''', diseases that are transmitted primarily by oral means may be caught through direct oral contact such as [[kiss]]ing, or by indirect contact such as by sharing a drinking glass or a cigarette. |

|||

* '''Transmission by direct contact''', Some diseases that are transmissible by direct contact include [[athlete's foot]], [[impetigo]] and [[wart]]s. |

|||

* '''Vehicle transmission''', transmission by an inanimate reservoir (food, water, soil).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.microbiologybook.org/Infectious%20Disease/Infectious%20Disease%20Introduction.htm|title=Clinical Infectious Disease – Introduction|website=microbiologybook.org|access-date=2017-04-19|archive-date=2017-04-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170420143405/http://www.microbiologybook.org/Infectious%20Disease/Infectious%20Disease%20Introduction.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Vertically transmitted infection|Vertical transmission]]''', directly from the mother to an [[embryo]], [[fetus]] or baby during [[pregnancy]] or [[childbirth]]. It can occur as a result of a [[pre-existing disease in pregnancy|pre-existing infection]] or one acquired during pregnancy. |

|||

* '''[[Iatrogenic]] transmission''', due to medical procedures such as [[Injection (medicine)|injection]] or [[organ transplant|transplantation]] of infected material. |

|||

* '''Vector-borne transmission''', transmitted by a [[Vector (epidemiology)|vector]], which is an [[organism]] that does not cause [[disease]] itself but that transmits infection by conveying [[pathogen]]s from one [[Host (biology)|host]] to another.<ref>[http://www.metapathogen.com/ Pathogens and vectors] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171005150918/http://www.metapathogen.com/ |date=2017-10-05 }}. ''MetaPathogen.com''.</ref> |

|||

The relationship between ''[[optimal virulence|virulence versus transmissibility]]'' is complex; with studies have shown that there were no clear relationship between the two.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hector |first1=Tobias E. |last2=Booksmythe |first2=Isobel |title=Digest: Little evidence exists for a virulence-transmission trade-off* |journal=Evolution |date=April 2019 |volume=73 |issue=4 |pages=858–859 |doi=10.1111/evo.13724 |pmid=30900249 |s2cid=85448255 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Acevedo |first1=Miguel A. |last2=Dillemuth |first2=Forrest P. |last3=Flick |first3=Andrew J. |last4=Faldyn |first4=Matthew J. |last5=Elderd |first5=Bret D. |title=Virulence-driven trade-offs in disease transmission: A meta-analysis* |journal=Evolution |date=April 2019 |volume=73 |issue=4 |pages=636–647 |doi=10.1111/evo.13692 |pmid=30734920 |s2cid=73418339 |url=https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/biosci_pubs/1193 |access-date=2022-06-28 |archive-date=2022-12-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221204210544/https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/biosci_pubs/1193/ |url-status=live }}</ref> There is still a small number of evidence that partially suggests a link between virulence and transmissibility.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ericson |first1=L. |last2=Burdon |first2=J. J. |last3=Müller |first3=W. J. |title=Spatial and temporal dynamics of epidemics of the rust fungus Uromyces valerianae on populations of its host Valeriana salina |journal=Journal of Ecology |date=August 1999 |volume=87 |issue=4 |pages=649–658 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2745.1999.00384.x |s2cid=86478171 |doi-access=free |bibcode=1999JEcol..87..649E }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Mideo |first1=N |last2=Alizon |first2=S |last3=Day |first3=T |title=Linking within- and between-host dynamics in the evolutionary epidemiology of infectious diseases |journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution |date=September 2008 |volume=23 |issue=9 |pages=511–517 |doi=10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.009|pmid=18657880 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Mordecai |first1=Erin A. |last2=Cohen |first2=Jeremy M. |last3=Evans |first3=Michelle V. |last4=Gudapati |first4=Prithvi |last5=Johnson |first5=Leah R. |last6=Lippi |first6=Catherine A. |last7=Miazgowicz |first7=Kerri |last8=Murdock |first8=Courtney C. |last9=Rohr |first9=Jason R. |last10=Ryan |first10=Sadie J. |last11=Savage |first11=Van |last12=Shocket |first12=Marta S. |last13=Stewart Ibarra |first13=Anna |last14=Thomas |first14=Matthew B. |last15=Weikel |first15=Daniel P. |title=Detecting the impact of temperature on transmission of Zika, dengue, and chikungunya using mechanistic models |journal=PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases |date=27 April 2017 |volume=11 |issue=4 |pages=e0005568 |doi=10.1371/journal.pntd.0005568|pmid=28448507 |pmc=5423694 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

== Колонизација == |

== Колонизација == |

||

| Ред 262: | Ред 364: | ||

* -{[https://web.archive.org/web/20180830220529/http://www.infectionwatch.info/ Infection] Information Resource}- |

* -{[https://web.archive.org/web/20180830220529/http://www.infectionwatch.info/ Infection] Information Resource}- |

||

* -{''[http://www.journals.elsevier.com/microbes-and-infection/ Microbes & Infection]'' (journal)}- |

* -{''[http://www.journals.elsevier.com/microbes-and-infection/ Microbes & Infection]'' (journal)}- |

||

* -{[http://www.woundsite.info/ Knowledge source for Health Care Professionals involved in Wound management]{{Мртва веза}} www.woundsite.info}- |

|||

* -{[http://www.cbc.ca/news/1.2802071 Table: Global deaths from communicable diseases, 2010] – Canadian Broadcasting Corp.}- |

* -{[http://www.cbc.ca/news/1.2802071 Table: Global deaths from communicable diseases, 2010] – Canadian Broadcasting Corp.}- |

||

Верзија на датум 9. март 2024. у 22:48

| Инфекција | |

|---|---|

| |

| False-colored electron micrograph showing a malaria sporozoite migrating through the midgut epithelium of a rat | |

| Специјалности | Infectious diseases |

| Узроци | bacterial, viral, parasitic, fungal, prion |

Инфективне болести су врста обољења људи и животиња изазваних спољним биолошким изазивачем; микроорганизмом (бактерија, паразит, гљивица, вирус), или беланчевином (прион).[1][2][3] Инфекција сама по себи није болест, јер она само понекад доводи до обољења. Инфективне болести исказују широки спектар могућих симптома и клиничких слика развоја болести. Симптоми се могу јавити у року од неколико дана, недеља, или чак година од заразе. Зависно од личног имунитета[4] и врсте инфекције, инфективне болести могу да изазову само незнатне симптоме и прођу без посебног лечења. Неке инфекције брзо изазивају драматичне здравствене сметње. У случају сепсе, организам реагује одбрамбеном реакцијом која изазива грозницу, убрзани пулс и ритам дисања, жеђ и умор. За прогнозу инфективне болести одлучујућа је способност имунског система да елиминише узрочника болести. Медицинска наука је развила ефикасне методе за борбу против многих инфективних болести (антибиотике за елиминисање бактерија, антимикотике за борбу против гљивица и виростатике против вируса). Против неких болести развијене су вакцине. За један број инфективних болести ни данас не постоји ефикасан лек. Проучавањем инфективних болести бави се инфектологија, а механизмима одбране огранизма бави се имунологија.[1]

Један корисник управо ради на овом чланку. Молимо остале кориснике да му допусте да заврши са радом. Ако имате коментаре и питања у вези са чланком, користите страницу за разговор.

Хвала на стрпљењу. Када радови буду завршени, овај шаблон ће бити уклоњен. Напомене

|

Infections can be caused by a wide range of pathogens, most prominently bacteria and viruses.[5] Hosts can fight infections using their immune systems. Mammalian hosts react to infections with an innate response, often involving inflammation, followed by an adaptive response.

Specific medications used to treat infections include antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, antiprotozoals,[6] and antihelminthics. Infectious diseases resulted in 9.2 million deaths in 2013 (about 17% of all deaths).[7] The branch of medicine that focuses on infections is referred to as infectious diseases.[8]

Узроци

Инфекције су узроковане инфективним агенсима, укључујући вирусе, вироиде, прионе, патогене бактерије, протозое, нематоде, као што су паразитске обле глисте и трихина, инсекти, као што су зглавкари, гриње, буве и уши, гљивице, лишаји и други макропаразити,[9][10] као што су пљоснати црви и други хелминти.

Домаћини се боре са инфекцијама користећи свој имунски систем. Сисарски домаћини реагирају на инфекције урођеним одговорима,[11] који често укључују упале, а затим следи адаптивни одговор.[12]

Када инфицира организам домаћина, узрочник инфекције се њиме користи како би се могао развијати и размножавати, обично на штету домаћина. Узрочници инфекције или патогени, ометају нормално функционисање организма домаћина што може имати негативне последице, попут хроничних рана које не зарастају, гангрене, губитка екстремитета и чак смрти. Упала је једна од реакција на инфекцију.

Патогенима се обично сматрају микроскопски организми и, поред горенаведених, ту су и разне врсте паразита и гљивица. Медицина инфективних болести се бави изучавањем патогена и инфекција. Инфекције су узрок заразних болести, али свака инфекција увек не изазива болест. Постоји више фактора који могу да имају утицај на то, као што су карактеристике самог микроорганизма - патогена: заразност, продорност, упорност, виталност, вирулентност и патогеност. Битни су и фактори попут начина уласка микроорганизма у тело домаћина, почетни број микроорганизама и њихова моћ. На пример стафилококе су обично безазалене када се налазе на кожи, али ако допру у стерилна подручја унутар организма, као што су зглобови или трбушна марамица, тада узрокују велике проблеме домаћину. Значајне су и карактеристике макроорганизма, домаћина, и његовог имунског система: снага имунитета генерално, тренутна снага имунитета и карактеристике околине. Овде се могу убројати климатски услови, али и социо-економски услови у којима живи нападнути организам (и патоген).

Подела инфекција према симптомима:

- инфекције код којих се не јављају видљиви симптоми болести,

- инфекције са слабо израженим симптомима,

- инфекције са видљиво израженим клиничким симптомима.

Само овај последњи тип се рачуна као заразна болест.

Infections are caused by infectious agents (pathogens) including:

- Bacteria (e.g. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Clostridium botulinum, and Salmonella spp.)

- Viruses and related agents such as viroids. (E.g. HIV, Rhinovirus, Lyssaviruses such as Rabies virus, Ebolavirus and Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2)

- Fungi, further subclassified into:

- Ascomycota, including yeasts such as Candida (the most common fungal infection); filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus; Pneumocystis species; and dermatophytes, a group of organisms causing infection of skin and other superficial structures in humans.[17]

- Basidiomycota, including the human-pathogenic genus Cryptococcus.[18]

- Parasites, which are usually divided into:[19]

- Unicellular organisms (e.g. malaria, Toxoplasma, Babesia)

- Macroparasites[20] (worms or helminths) including nematodes such as parasitic roundworms and pinworms, tapeworms (cestodes), and flukes (trematodes, such as schistosomes). Diseases caused by helminths are sometimes termed infestations, but are sometimes called infections.

- Arthropods such as ticks, mites, fleas, and lice, can also cause human disease, which conceptually are similar to infections, but invasion of a human or animal body by these macroparasites is usually termed infestation.

- Prions (although they do not secrete toxins)

Инфекције према узроку

Бактеријске и вирусне инфекције могу узроковати сличне симптоме у које се могу убројати осећај слабости, повишена телесна температура и дрхтање. Понекад је медицинском особљу тешко да утврдити узрок дате инфекције. Веома је важно да се уочи разлика између инфекција према њиховом узроку како би се одредио адекватан третман и терапија. Вирусне инфекције се не могу излечити применом антибиотика.

| Карактеристике | Вирус | Бактерија |

|---|---|---|

| Типски симптоми | Вирусне инфекције обично погађају цели систем, односно више органа истовремено: цурење носа, зачепљење синуса, кашаљ, болови у телу итд. Понекад погађају само један део тела, као код конјуктивитиса и херпеса. Мали број вирусних инфекција је болан, попут херпеса. Бол се може описати као свраб или печење. | Класични симптоми бактеријске инфекције се манифестују локално: црвенило, топлота, оток и бол. Бол је управо значајан симптом који се јавља само у погођеном делу тела. Нпр. ако се рана посекотине зарази бактеријама, осјећа се бол. Бол у грлу изазван бактеријском инфекцијом често је више изражен на једној страни грла. Исто је и код ушију, ако је у питању само једно уво, онда је узрок заразе вероватно бактеријски. Гнојне инфекције нису увек бактеријске. |

| Узрок | Патогени вируси | Патогене бактерије |

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of an infection depend on the type of disease. Some signs of infection affect the whole body generally, such as fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss, fevers, night sweats, chills, aches and pains. Others are specific to individual body parts, such as skin rashes, coughing, or a runny nose.[21]

In certain cases, infectious diseases may be asymptomatic for much or even all of their course in a given host. In the latter case, the disease may only be defined as a "disease" (which by definition means an illness) in hosts who secondarily become ill after contact with an asymptomatic carrier. An infection is not synonymous with an infectious disease, as some infections do not cause illness in a host.[22]

Bacterial or viral

As bacterial and viral infections can both cause the same kinds of symptoms, it can be difficult to distinguish which is the cause of a specific infection.[23] Distinguishing the two is important, since viral infections cannot be cured by antibiotics whereas bacterial infections can.[24]

| Characteristic | Viral infection | Bacterial infection |

|---|---|---|

| Typical symptoms | In general, viral infections are systemic. This means they involve many different parts of the body or more than one body system at the same time; i.e. a runny nose, sinus congestion, cough, body aches etc. They can be local at times as in viral conjunctivitis or "pink eye" and herpes. Only a few viral infections are painful, like herpes. The pain of viral infections is often described as itchy or burning.[23] | The classic symptoms of a bacterial infection are localized redness, heat, swelling and pain. One of the hallmarks of a bacterial infection is local pain, pain that is in a specific part of the body. For example, if a cut occurs and is infected with bacteria, pain occurs at the site of the infection. Bacterial throat pain is often characterized by more pain on one side of the throat. An ear infection is more likely to be diagnosed as bacterial if the pain occurs in only one ear.[23] A cut that produces pus and milky-colored liquid is most likely infected.[25] |

| Cause | Pathogenic viruses | Pathogenic bacteria |

Pathophysiology

There is a general chain of events that applies to infections, sometimes called the chain of infection[26] or transmission chain. The chain of events involves several steps – which include the infectious agent, reservoir, entering a susceptible host, exit and transmission to new hosts. Each of the links must be present in a chronological order for an infection to develop. Understanding these steps helps health care workers target the infection and prevent it from occurring in the first place.[27]

Colonization

Infection begins when an organism successfully enters the body, grows and multiplies. This is referred to as colonization. Most humans are not easily infected. Those with compromised or weakened immune systems have an increased susceptibility to chronic or persistent infections. Individuals who have a suppressed immune system are particularly susceptible to opportunistic infections. Entrance to the host at host–pathogen interface, generally occurs through the mucosa in orifices like the oral cavity, nose, eyes, genitalia, anus, or the microbe can enter through open wounds. While a few organisms can grow at the initial site of entry, many migrate and cause systemic infection in different organs. Some pathogens grow within the host cells (intracellular) whereas others grow freely in bodily fluids.[28]

Wound colonization refers to non-replicating microorganisms within the wound, while in infected wounds, replicating organisms exist and tissue is injured.[29] All multicellular organisms are colonized to some degree by extrinsic organisms, and the vast majority of these exist in either a mutualistic or commensal relationship with the host. An example of the former is the anaerobic bacteria species, which colonizes the mammalian colon, and an example of the latter are the various species of staphylococcus that exist on human skin. Neither of these colonizations are considered infections. The difference between an infection and a colonization is often only a matter of circumstance. Non-pathogenic organisms can become pathogenic given specific conditions, and even the most virulent organism requires certain circumstances to cause a compromising infection. Some colonizing bacteria, such as Corynebacteria sp. and Viridans streptococci, prevent the adhesion and colonization of pathogenic bacteria and thus have a symbiotic relationship with the host, preventing infection and speeding wound healing.

The variables involved in the outcome of a host becoming inoculated by a pathogen and the ultimate outcome include:

- the route of entry of the pathogen and the access to host regions that it gains

- the intrinsic virulence of the particular organism

- the quantity or load of the initial inoculant

- the immune status of the host being colonized

As an example, several staphylococcal species remain harmless on the skin, but, when present in a normally sterile space, such as in the capsule of a joint or the peritoneum, multiply without resistance and cause harm.[33]

An interesting fact that gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, 16S ribosomal RNA analysis, omics, and other advanced technologies have made more apparent to humans in recent decades is that microbial colonization is very common even in environments that humans think of as being nearly sterile. Because it is normal to have bacterial colonization, it is difficult to know which chronic wounds can be classified as infected and how much risk of progression exists. Despite the huge number of wounds seen in clinical practice, there are limited quality data for evaluated symptoms and signs. A review of chronic wounds in the Journal of the American Medical Association's "Rational Clinical Examination Series" quantified the importance of increased pain as an indicator of infection.[34] The review showed that the most useful finding is an increase in the level of pain [likelihood ratio (LR) range, 11–20] makes infection much more likely, but the absence of pain (negative likelihood ratio range, 0.64–0.88) does not rule out infection (summary LR 0.64–0.88).

Disease

Disease can arise if the host's protective immune mechanisms are compromised and the organism inflicts damage on the host. Microorganisms can cause tissue damage by releasing a variety of toxins or destructive enzymes. For example, Clostridium tetani releases a toxin that paralyzes muscles, and staphylococcus releases toxins that produce shock and sepsis. Not all infectious agents cause disease in all hosts. For example, less than 5% of individuals infected with polio develop disease.[35] On the other hand, some infectious agents are highly virulent. The prion causing mad cow disease and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease invariably kills all animals and people that are infected.[36]

Persistent infections occur because the body is unable to clear the organism after the initial infection. Persistent infections are characterized by the continual presence of the infectious organism, often as latent infection with occasional recurrent relapses of active infection. There are some viruses that can maintain a persistent infection by infecting different cells of the body. Some viruses once acquired never leave the body. A typical example is the herpes virus, which tends to hide in nerves and become reactivated when specific circumstances arise.[37]

Persistent infections cause millions of deaths globally each year.[38] Chronic infections by parasites account for a high morbidity and mortality in many underdeveloped countries.[39][40]

Transmission

For infecting organisms to survive and repeat the infection cycle in other hosts, they (or their progeny) must leave an existing reservoir and cause infection elsewhere. Infection transmission can take place via many potential routes:[41]

- Droplet contact, also known as the respiratory route, and the resultant infection can be termed airborne disease. If an infected person coughs or sneezes on another person the microorganisms, suspended in warm, moist droplets, may enter the body through the nose, mouth or eye surfaces.

- Fecal-oral transmission, wherein foodstuffs or water become contaminated (by people not washing their hands before preparing food, or untreated sewage being released into a drinking water supply) and the people who eat and drink them become infected. Common fecal-oral transmitted pathogens include Vibrio cholerae, Giardia species, rotaviruses, Entamoeba histolytica, Escherichia coli, and tape worms.[42] Most of these pathogens cause gastroenteritis.

- Sexual transmission, with the result being called sexually transmitted infection.

- Oral transmission, diseases that are transmitted primarily by oral means may be caught through direct oral contact such as kissing, or by indirect contact such as by sharing a drinking glass or a cigarette.

- Transmission by direct contact, Some diseases that are transmissible by direct contact include athlete's foot, impetigo and warts.

- Vehicle transmission, transmission by an inanimate reservoir (food, water, soil).[43]

- Vertical transmission, directly from the mother to an embryo, fetus or baby during pregnancy or childbirth. It can occur as a result of a pre-existing infection or one acquired during pregnancy.

- Iatrogenic transmission, due to medical procedures such as injection or transplantation of infected material.

- Vector-borne transmission, transmitted by a vector, which is an organism that does not cause disease itself but that transmits infection by conveying pathogens from one host to another.[44]

The relationship between virulence versus transmissibility is complex; with studies have shown that there were no clear relationship between the two.[45][46] There is still a small number of evidence that partially suggests a link between virulence and transmissibility.[47][48][49]

Колонизација

Под колонизацијом се подразумева насељавање и опстанак микроорганизама у телу домаћина. Сви макроорганизми или вишећелијски организми су у одређеној мери колонизовани од спољашњњим организама и у већини случајева њихово присуство није штетно или је чак и корисно за домаћина. Овде се могу споменути анаеробне (није им потребан кисеоник за живот) бактерије које колонизују црева сисара и стафилококе које живе на кожи. Ниједан од ових примера не представља инфекцију. Разлика између колонизације и инфекције је ствар околности. Непатогени организми у одређеним условима могу постати патогени. С друге стране, чак и најзаразнији патогени не могу изазавати инфекцију, ако нису испуњени потребни услови. Неки од примера су и бактерије Corynebacteria и Viridans streptococci које спречавају продор и колонизацију патогених бактерија и тако остварују симбиотички однос са домаћином, спречавајући инфекције и поспешујући зарастање рана.

Најзначајније инфективне болести

Бактеријске

| Болест | Изазивач(и) |

| антракс | Bacillus anthracis |

| бактеријски менингитис | група B streptococcus (код новорођенчади) Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae (код деце) N. meningitidis, S. pneumoniae, L. monocytogenes, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (код одраслих) |

| ботулизам | Clostridium botulinum |

| болест после мачје огреботине | Bartonella |

| бруцелоза | Brucella spp. |

| велики кашаљ | Bordetella pertussis |

| гонореја | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| дифтерија | Corynebacterium diphtheriae |

| епидемијски тифус | Rickettsia prowazekii |

| ешерихија коли | Corynebacterium diphtheriae |

| импетиго | Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes |

| кампилобактериоза | Campylobacter jejuni |

| колера | Vibrio cholerae |

| крпељни тифус | Coxiella burnetii |

| куга | Yersinia pestis |

| лајмска болест | Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia garinii |

| легионарска болест | Legionella |

| лепра | Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium lepromatosis |

| лептоспироза | Leptospira interrogans |

| листериоза | Listeria monocytogenes |

| мелиоидоза | Burkholderia pseudomallei |

| метицилин резистентни стафилококус ауреус | Staphylococcus aureus |

| пнеумококална пнеумонија | Streptococcus pneumoniae (и друге) |

| реуматична грозница | Streptococcus pyogenes |

| роки маунтин тачкаста грозница | Rickettsia rickettsii |

| салмонелоза | Salmonella |

| сифилис | Treponema pallidum pallidum |

| тетанус | Clostridium tetani |

| тифус | Rickettsiae |

| тифоидна грозница | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi |

| трахом | Chlamydia trachomatis |

| туберкулоза | Mycobacterium tuberculosis (и друге) |

| туларемија | Francisella tularensis |

| уринарне инфекције | Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrheae |

| хламидијаза | Chlamydia psittaci |

| шарлах | Streptococcus pyogenes |

| шигелоза | Shigella |

Паразитске

- изазивач: протозое

- изазивач: црви - хелминтијазе

- изазивач: спољни паразити - ектопаразитозе

- инфекција вашима

Гљивичне

| болест | изазивач(и) |

| аспергилоза | Aspergillus fumigatus (и друге) |

| атлетско стопало | Trichophyton rubrum, Epidermophyton floccosum |

| бластомикоза | Blastomyces dermatitidis |

| Кандидијаза | Candida albicans (и друге) |

| кокцидиоидомикоза | Coccidioides immitis, C. posadasii |

| криптококоза | Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus gattii |

| хистоплазмоза | Histoplasma capsulatum |

Вирусне

- прехлада (ринитис)

- грип

- хепатитис (А, Б, Ц, Д, Е, Ф, Г)

- полиомијелитис

- беснило

- ебола

- жута грозница

- херпес

- велике богиње

- мале богиње

- црвенка

- сида

- варичела

Прионске

Референце

- ^ а б Mandel GL, Bannett JE, Dolin R, ур. (2000). Principles and Practise of Infectious Diseases (5 изд.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70089-X. ISBN 044307593X.

- ^ Definition of "infection" from several medical dictionaries – Приступљено 2012-04-03

- ^ „Utilizing antibiotics agents effectively will preserve present day medication”. News Ghana. 21. 11. 2015. Приступљено 21. 11. 2015.

- ^ Thomas J. Kindt; Richard A. Goldsby; Barbara Anne Osborne; Janis Kuby (2006). Kuby Immunology (6 изд.). New York: W H Freeman and company. ISBN 1429202114.

- ^ Sehgal, Mukul; Ladd, Hugh J.; Totapally, Balagangadhar (2020-12-01). „Trends in Epidemiology and Microbiology of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock in Children”. Hospital Pediatrics (на језику: енглески). 10 (12): 1021—1030. ISSN 2154-1663. PMID 33208389. S2CID 227067133. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2020-0174

. Архивирано из оригинала 2021-04-13. г. Приступљено 2021-03-26.

. Архивирано из оригинала 2021-04-13. г. Приступљено 2021-03-26.

- ^ „Antiprotozoal Drugs”. TheFreeDictionary.com. Архивирано из оригинала 2022-01-22. г. Приступљено 2022-04-22.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17. 12. 2014). „Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study”. Lancet. 385 (9963): 117—71. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

- ^ „Infectious Disease, Internal Medicine”. Association of American Medical Colleges. Архивирано из оригинала 2015-02-06. г. Приступљено 2015-08-20. „Infectious disease is the subspecialty of internal medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of communicable diseases of all types, in all organs, and in all ages of patients.”

- ^ Poulin, Robert; Randhawa, Haseeb S. (фебруар 2015). „Evolution of parasitism along convergent lines: from ecology to genomics”. Parasitology. 142 (Suppl 1): S6—S15. PMC 4413784

. PMID 24229807. doi:10.1017/S0031182013001674.

. PMID 24229807. doi:10.1017/S0031182013001674.

- ^ Poulin, Robert (2011). Rollinson, D.; Hay, S. I., ур. The Many Roads to Parasitism: A Tale of Convergence. Advances in Parasitology. Academic Press. стр. 27—28. ISBN 978-0-12-385897-9.

- ^ Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M (2001). Immunobiology (Fifth изд.). New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7.

- ^ Signore, Alberto (2013). „About inflammation and infection” (PDF). EJNMMI Research. 8 (3).

- ^ Bentivoglio, M; Pacini, P (1995). „Filippo Pacini: A determined observer” (PDF). Brain Research Bulletin. 38 (2): 161—5. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.362.6850

. PMID 7583342. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(95)00083-Q.

. PMID 7583342. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(95)00083-Q.

- ^ Howard-Jones, N (1984). „Robert Koch and the cholera vibrio: a centenary”. BMJ. 288 (6414): 379—81. PMC 1444283

. PMID 6419937. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6414.379.

. PMID 6419937. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6414.379.

- ^ Stephenson-Famy, A; Gardella, C (децембар 2014). „Herpes Simplex Virus Infection During Pregnancy.”. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 41 (4): 601—14. PMID 25454993. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2014.08.006.

- ^ Steiner, I; Benninger, F (децембар 2013). „Update on herpes virus infections of the nervous system.”. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 13 (12): 414. PMID 24142852. doi:10.1007/s11910-013-0414-8.

- ^ „Types of Fungal Diseases”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (на језику: енглески). 2019-06-27. Архивирано из оригинала 2020-04-01. г. Приступљено 2019-12-09.

- ^ Mada, Pradeep Kumar; Jamil, Radia T.; Alam, Mohammed U. (2019), „Cryptococcus (Cryptococcosis)”, StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613714, Архивирано из оригинала 2020-06-19. г., Приступљено 2019-12-09

- ^ „About Parasites”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (на језику: енглески). 2019-02-25. Архивирано из оригинала 2019-12-25. г. Приступљено 2019-12-09.

- ^ Brown, Peter J. (1987). „Microparasites and Macroparasites”. Cultural Anthropology. 2 (1): 155—71. JSTOR 656401. doi:10.1525/can.1987.2.1.02a00120.

- ^ „Runny Nose: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment”. Cleveland Clinic. Архивирано из оригинала 2022-05-10. г. Приступљено 2022-04-22.

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, ур. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th изд.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ а б в „NIPA - Bacteria - Bacterial vs. Viral infections”. www.antibiotics-info.org. Архивирано из оригинала 2023-11-10. г. Приступљено 2023-11-10.

- ^ Robert N. Golden; Fred Peterson (2009). The Truth About Illness and Disease. Infobase Publishing. стр. 181. ISBN 978-1438126371.

- ^ „Infection”. Rencare. Архивирано из оригинала 5. 3. 2012. г. Приступљено 4. 7. 2013.

- ^ „Infection Cycle Symptoms and Treatment”. Infection Cycle (на језику: енглески). Архивирано из оригинала 2023-11-10. г. Приступљено 2023-11-10.

- ^ National Institutes of Health (US); Study, Biological Sciences Curriculum (2007), „Understanding Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases”, NIH Curriculum Supplement Series [Internet] (на језику: енглески), National Institutes of Health (US), Архивирано из оригинала 2023-06-26. г., Приступљено 2023-11-17

- ^ Peterson, Johnny W. (1996). Bacterial Pathogenesis (на језику: енглески). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 9780963117212. PMID 21413346. Архивирано из оригинала 2016-04-25. г. Приступљено 2022-10-20.

- ^ Negut, Irina; Grumezescu, Valentina; Grumezescu, Alexandru Mihai (2018-09-18). „Treatment Strategies for Infected Wounds”. Molecules. 23 (9): 2392. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 6225154

. PMID 30231567. doi:10.3390/molecules23092392

. PMID 30231567. doi:10.3390/molecules23092392  .

.

- ^ Duerkop, Breck A; Hooper, Lora V (2013-07-01). „Resident viruses and their interactions with the immune system”. Nature Immunology (на језику: енглески). 14 (7): 654—59. PMC 3760236

. PMID 23778792. doi:10.1038/ni.2614.

. PMID 23778792. doi:10.1038/ni.2614.

- ^ „Bacterial Pathogenesis at Washington University”. StudyBlue. St. Louis. Архивирано из оригинала 2016-12-03. г. Приступљено 2016-12-02.

- ^ „Print Friendly”. www.lifeextension.com. Архивирано из оригинала 2016-12-02. г. Приступљено 2016-12-02.

- ^ Tong, Steven Y. C.; Davis, Joshua S.; Eichenberger, Emily; Holland, Thomas L.; Fowler, Vance G. (2015). „Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 28 (3): 603—661. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 4451395

. PMID 26016486. doi:10.1128/CMR.00134-14.

. PMID 26016486. doi:10.1128/CMR.00134-14.

- ^ Reddy M, Gill SS, Wu W, et al. (фебруар 2012). „Does this patient have an infection of a chronic wound?”. JAMA. 307 (6): 605—11. PMID 22318282. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.98.

- ^ „Polio: Questions and Answers” (PDF). immunize.org. Архивирано (PDF) из оригинала 2022-10-09. г. Приступљено 9. 7. 2021.

- ^ Trent, Ronald J (2005). „Infectious Diseases”. Molecular Medicine: 193—220. ISBN 9780126990577. PMC 7149788

. doi:10.1016/B978-012699057-7/50008-4.

. doi:10.1016/B978-012699057-7/50008-4.

- ^ Rouse, Barry T.; Sehrawat, Sharvan (2010). „Immunity and immunopathology to viruses: what decides the outcome?”. Nature Reviews Immunology (на језику: енглески). 10 (7): 514—526. ISSN 1474-1741. PMC 3899649

. PMID 20577268. doi:10.1038/nri2802.

. PMID 20577268. doi:10.1038/nri2802.

- ^ „Chronic Infection Information”. persistentinfection.net. Архивирано из оригинала 22. 7. 2015. г. Приступљено 2010-01-14.

- ^ Torgerson, Paul R.; Devleesschauwer, Brecht; Praet, Nicolas; Speybroeck, Niko; Willingham, Arve Lee; Kasuga, Fumiko; Rokni, Mohammad B.; Zhou, Xiao-Nong; Fèvre, Eric M.; Sripa, Banchob; Gargouri, Neyla (2015-12-03). „World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 11 Foodborne Parasitic Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis”. PLOS Medicine. 12 (12): e1001920. ISSN 1549-1277. PMC 4668834

. PMID 26633705. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001920

. PMID 26633705. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001920  .

.

- ^ Hotez, Peter J.; Bundy, Donald A. P.; Beegle, Kathleen; Brooker, Simon; Drake, Lesley; de Silva, Nilanthi; Montresor, Antonio; Engels, Dirk; Jukes, Matthew (2006), Jamison, Dean T.; Breman, Joel G.; Measham, Anthony R.; Alleyne, George, ур., „Helminth Infections: Soil-transmitted Helminth Infections and Schistosomiasis”, Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (2nd изд.), Washington (DC): World Bank, ISBN 978-0-8213-6179-5, PMID 21250326, Архивирано из оригинала 2016-10-10. г., Приступљено 2021-08-13

- ^ „How Infections Spread”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1. 1. 2016. Архивирано из оригинала 2. 6. 2023. г. Приступљено 17. 10. 2021.

- ^ Intestinal Parasites and Infection Архивирано 2010-10-28 на сајту Wayback Machine fungusfocus.com – Retrieved on 2010-01-21

- ^ „Clinical Infectious Disease – Introduction”. microbiologybook.org. Архивирано из оригинала 2017-04-20. г. Приступљено 2017-04-19.

- ^ Pathogens and vectors Архивирано 2017-10-05 на сајту Wayback Machine. MetaPathogen.com.

- ^ Hector, Tobias E.; Booksmythe, Isobel (април 2019). „Digest: Little evidence exists for a virulence-transmission trade-off*”. Evolution. 73 (4): 858—859. PMID 30900249. S2CID 85448255. doi:10.1111/evo.13724

.

.

- ^ Acevedo, Miguel A.; Dillemuth, Forrest P.; Flick, Andrew J.; Faldyn, Matthew J.; Elderd, Bret D. (април 2019). „Virulence-driven trade-offs in disease transmission: A meta-analysis*”. Evolution. 73 (4): 636—647. PMID 30734920. S2CID 73418339. doi:10.1111/evo.13692. Архивирано из оригинала 2022-12-04. г. Приступљено 2022-06-28.

- ^ Ericson, L.; Burdon, J. J.; Müller, W. J. (август 1999). „Spatial and temporal dynamics of epidemics of the rust fungus Uromyces valerianae on populations of its host Valeriana salina”. Journal of Ecology. 87 (4): 649—658. Bibcode:1999JEcol..87..649E. S2CID 86478171. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.1999.00384.x

.

.

- ^ Mideo, N; Alizon, S; Day, T (септембар 2008). „Linking within- and between-host dynamics in the evolutionary epidemiology of infectious diseases”. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 23 (9): 511—517. PMID 18657880. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.009.

- ^ Mordecai, Erin A.; Cohen, Jeremy M.; Evans, Michelle V.; Gudapati, Prithvi; Johnson, Leah R.; Lippi, Catherine A.; Miazgowicz, Kerri; Murdock, Courtney C.; Rohr, Jason R.; Ryan, Sadie J.; Savage, Van; Shocket, Marta S.; Stewart Ibarra, Anna; Thomas, Matthew B.; Weikel, Daniel P. (27. 4. 2017). „Detecting the impact of temperature on transmission of Zika, dengue, and chikungunya using mechanistic models”. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 11 (4): e0005568. PMC 5423694

. PMID 28448507. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005568

. PMID 28448507. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005568  .

.

Литература

- Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M (2001). Immunobiology (Fifth изд.). New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7.</ref> који често укључују упале, а затим следи адаптивни одговор.<ref>Signore, Alberto (2013). „About inflammation and infection” (PDF). EJNMMI Research. 8 (3).

- Poulin, Robert (2011). Rollinson, D.; Hay, S. I., ур. The Many Roads to Parasitism: A Tale of Convergence. Advances in Parasitology. Academic Press. стр. 27—28. ISBN 978-0-12-385897-9.

- Stvrtinová V, Jakubovský J, Hulín I (1995). „Inflammation and Fever”. Pathophysiology: Principles of Disease. Computing Centre, Slovak Academy of Sciences: Academic Electronic Press. Архивирано из оригинала 18. 6. 2007. г.

- Janeway CA, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik MJ (2005). Immunobiology. (6th изд.). Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-443-07310-6.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walters P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (Fourth изд.). New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- Janeway C (2005). Immunobiology (6th изд.). Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-443-07310-6.

- Klingemann HG (2010). „Development and testing of NK cell lines”. Ур.: Lotze MT, Thompson AW. Natural killer cells - Basic Science and Clinical applications. стр. 169—75.

- Doan T (2008). Immunology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. стр. 172. ISBN 978-0-7817-9543-2.

Спољашње везе

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA)

- Infectious Disease Index of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)

- Vaccine Research Center Information concerning vaccine research clinical trials for Emerging and re-Emerging Infectious Diseases.

- Infection Information Resource

- Microbes & Infection (journal)

- Table: Global deaths from communicable diseases, 2010 – Canadian Broadcasting Corp.

| Молимо Вас, обратите пажњу на важно упозорење у вези са темама из области медицине (здравља). |